In the spring of 1970, as a prospective middle-round NFL draftee, I was haunted by a recurring nightmare. On a practice field somewhere, between two blocking dummies, I faced a monstrous offensive tackle, who sat poised and quivering in his stance. To the tackle's left, on the far side of one bag, a center hunkered over a football. Behind the center, a quarterback. Behind the quarterback, a running back, whom I was required to bring down after shedding the tackle's block -- a ritual of pain known as the Nutcracker Drill.

I never succeeded. Night after night, my failure unfolded with a sickening regularity. Dead-eyed, an inhuman mass of rippling muscle, with a machine-like mastery of his brutal technique, the tackle, at the snap of the football, would slam his fists into my rib cage. Lifting me up, he would tip me over backwards, pinning me to the turf like a bug as the running back went skittering by.

Squirming helplessly there, I could see my embarrassed teammates turning away. Then a growling, gap-toothed coach would straddle me, leering down in disgust. "Get up! Go again!" he would bellow. I would shake my head no. "Coward!" he would roar. Still, I would refuse. "You are what I loathe," he would growl. "A loser." And with that, I would wake up.

While most of the figures in the dream were obscure, the coach was not, for he was none other than Vincent T. Lombardi, then in the final year of his life, now the subject of an eye-opening new biography by David Maraniss, "When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi."

I wanted no part of him. Of all NFL coaches, Lombardi, I knew, was the one coach who could expose me for what I was. A loathsome creature of some indeterminate species. Certainly not a man. Something on the pathetic periphery of masculinity. Without heart. A defeatist. A loser.

It was exactly this kind of fear that always made playing football a mixed experience for me, that drained the joy from a game I should have loved unconditionally. Fear of not pleasing the coach. Of not measuring up. In this violent game, what frightened me was not getting hit but being subjected to the scornful eye of the man above me. It took me years to understand this fear -- and by the time I did, I had to wonder if I had subjected my own sons, whom I had vowed never to treat the way I had been treated, to the same thing.

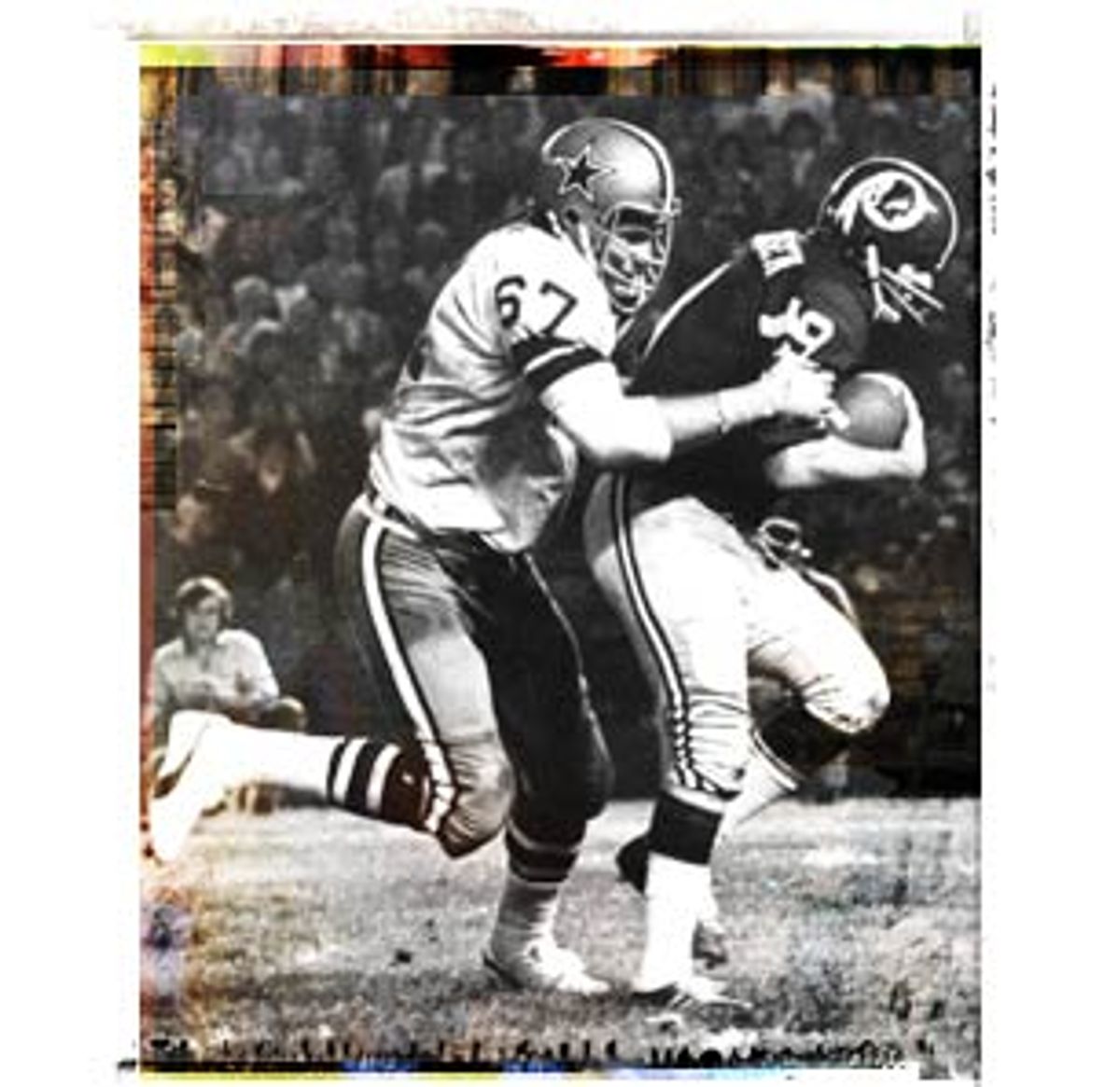

As it happened, I was spared the experience of playing for Lombardi, but not of escaping his legacy of shame. For I was drafted by a team that shared my fear of Lombardi's scrutiny -- that in fact had twice been humiliated by the Lombardi juggernaut -- Tom Landry's Dallas Cowboys. In their first crushing defeat by Lombardi's Packers, in the 1966 NFL Championship Game, which the Cowboys lost when Packer safety Tom Brown intercepted a pass in the Packer end zone, snuffing a game-winning Cowboy drive as time expired, the Cowboys were deemed too inexperienced, too new to the pressures of championship football to succeed at that level. But after their second numbing defeat, in the legendary "Ice Bowl"Championship Game in 1967, the very character of the club came into question, not only by fans and by sportswriters, but by the Packer players themselves. As Maraniss reports, the Packers were nothing short of disdainful of their Cowboy opponents. "We had their number," said Packer receiver Max McGee. "Lombardi had the hex on Landry." Other players observed that Cowboy receiver Bob Hayes unwittingly gave away plays by putting his hands in his pockets for runs, pulling them out for passes. The consensus was that the Cowboys didn't have the goods.

In an attempt to incorporate the Lombardi mystique, since it was impossible to defeat it, Cowboy General Manager Tex Schramm acquired three of the Packers' aging veterans. Uncharacteristically, Schramm, in making this move, overrode the strong objections of his coach, who reportedly wanted nothing to do with former Packers. But here they came anyway: linebacker Lee Roy Caffey, offensive tackle Forrest Gregg and cornerback Herb Adderley.

Adderley was the first of the Packer veterans to join the club, and for a time he resided with the more transient players, in a Dallas Holiday Inn. That's where I got to know him. Because he had gone where I feared to go, into the valley of the shadow of Lombardi, and emerged victorious, like a triumphant knight, Herb from the beginning was someone special to me. He was disarmingly open and friendly -- unusual for a veteran of his stature, who normally wouldn't pass the time of day with an obscure rookie. On more than one occasion, Herb joined me for a meal, and until he arranged for his own transportation, often rode with me to practice.

Of course I asked him about Lombardi. Yes, Lombardi could be brutal, Herb confirmed, but he also felt that characteristic of his coach was in service of something else. He talked about the togetherness of the Packers, the love the players had for one another, the amazing feats they were able to accomplish -- all out of a passion that had been inspired by Lombardi. But was it because of Lombardi, or in spite of him, that those feelings arose? I didn't have the nerve to ask the question, but one thing was certain. If Herb was a product of Lombardi, then Lombardi the man couldn't be as bleak as I'd imagined.

I was beginning to wonder, though, about Landry. By this time, I had been exposed to him for several months, and it was becoming clear that the two coaches occupied alternative football universes. Squat, blunt, volatile, Lombardi was an earthy Italian who valued simplicity and directness, while Landry was tall and aloof, a born-again Christian who had an almost prissy aversion to anything of the earth. An industrial engineer and World War II bomber pilot, Landry valued intellect over instinct, thought over feeling, science over the chaos of Lombardi's emotional alchemy. As far as coach Landry was concerned, players were responsible for their own motivation, while his job was to put them in position to make plays. The schemes he devised to accomplish this task were labyrinthine. While Lombardi's defense might be described as "Tackle the man with the ball," Landry's Flex defense required recognition of offensive patterns, internalization of the probable outcomes of those patterns and a corresponding reaction. Locating the football only came after following the branches of his logic tree -- a counterintuitive approach that could take years to master.

For a defensive end, for example -- which was my position -- if you were in the off-set of the Flex, your key was not the immediate threat of the gigantic tackle across from you, who wanted to grind you into hominy grits, but rather the guard positioned next to the tackle, who was hardly a concern. It was the movement of the guard that dictated whether you met the tackle with your outside shoulder or simply caromed off him to slide inside if the guard happened to be pulling -- all according to some larger plan that only Landry understood. The advantage of this approach, for me, was that it eliminated those head-to-head encounters with much bigger players that I could never fail to lose, giving me instead a gap to fill on one side of the tackle or the other, a contest I could always hope to win. For this reason, Landry, unlike Lombardi, was not a big proponent of the Nutcracker Drill, since it simply didn't serve him -- which I also found appealing.

But what would happen, I wondered, if a truly great player were inserted into this mechanism, someone hard-wired to his instincts, who hadn't been trained to ignore them -- someone gifted like Herb, a refugee from the instinctive world of Lombardi? What would happen? Herb shrugged off the notion, saying he was just happy to have an opportunity to play football. But as we rode out to practice on those hot, late summer afternoons, sometimes, it seemed, I could smell the smoke.

That was a private thought, of course, one I was reluctant to share with teammates. What I was willing to share with them was my enthusiasm for Herb.

No need, though, as it turned out, because everybody was enthusiastic about him. A consummate professional, sporting a glittering Packer Super Bowl ring, Herb, who is black, was a magnetic figure in the locker room, for both black and white alike. "Peace, love and happiness" was how he concluded nearly every exchange. "Brother A" was what he came to be called. Herb's soothing presence in the locker room defused racial tensions that had plagued the team for years.

On the field, Herb was equally impressive. Even at the age of 31, the future Hall of Famer moved with the grace of a gazelle. He could hang in the air like Dr. J. His instincts were impeccable. Predictably, however, his technique was in conflict with the technique required of a cornerback to play Landry's Flex. Instead of reading the on-side tackle and guard for run, as Landry required, Herb was doing what he had done for Lombardi the previous nine years, focusing on the receiver, peripherally picking up the main flow of action, reacting to what he saw. For a time, it didn't matter. That initial season, as Herb made a mighty contribution to the first-ever Cowboy Super Bowl run, and again, in '71, as the Cowboys achieved the pinnacle with Herb as co-captain, coach Landry let his consternation slide. The following season, however, as younger players began to develop enough to step in, things changed. Abruptly, for Herb, it got ugly.

In Dallas, watching game films was a three-hour marathon, with all players and staff present, unlike other teams, who split off into position groups to watch films. During these sessions, Landry himself ran the projector, going over the performance of every player on every play. If you'd had a bad game, watching game films could be an excruciating experience. Some players, suspecting they were in for it, took barbiturates to get through the sessions. Their armpit sweat rings would meet across their chests.

"Clueing" was what Tom called Herb's technique. And in one session during the '72 season, the refrain rang like a sour mantra: "Herb, you're clueing again." Coach Landry had a habit of transposing words, names, numbers, and he was doing that now, substituting "clueing" -- a bit of his own terminology -- for what he really meant to say, which was that Herb, again, was guessing. In Landry's system, "guessing," reacting instinctively, was a cardinal sin. If you followed his keys, took his clues, then your actions were predicated on a set of mathematical probabilities, gleaned from hours of study, rather than on the vagaries of instinct, which lacked accuracy, certainty, conformity with the assembly line performance of the other defensive players. "Guessing," for Tom, could too easily become an excuse, and there was no room for excuses, either in football or in life.

"Herb, you're clueing again!" The anger in Tom's voice, as the meeting progressed, escalated out of all proportion, and finally Herb rose to defend himself. It was an unprecedented moment for the team. No player had ever challenged the coach. Unaccustomed to Tom's habit of transposition, Herb had no idea what Tom was talking about with his "clueing" criticism. Angry and confused, Herb snapped something back at him, then left the room. The moment was quickly forgotten by the players, but not by the coach. Not long afterwards, during a game with the Giants, Herb was benched after swatting down a potential touchdown pass. Out of position again, he had been reacting instinctively. Despite the positive outcome of the play, it was all Tom could take.

"Herb, you've got to play the defense like everybody else!"

"You mean I'm supposed to let a guy run by me and catch a touchdown pass?"

"Yes, if that's what your keys tell you to do!"

"No. I don't play that way."

"Then you won't play at all."

The confrontation took place privately at halftime. When we took the field for the second half, Charlie Waters was in Herb's place. Herb watched the rest of the game from the sidelines.

Over the next few weeks Herb continued to start, but was spelled by Waters, for increasing periods of time. Then, before a game with the Chargers, Herb was summoned to a meeting with Landry. In the meeting Herb was told that his midseason grades were poor, that he had become a detriment to the team for harassing the younger defensive backs during practice.

Herb stared at Landry in disbelief. Maybe he was having problems with coverage, but he hadn't been harassing his teammates. If anything, he had been a mentor to the younger players, generously offering his help.

Said Landry: "Waters is the starter now. Stay or leave, I don't care."

Herb left the meeting without saying a word. He was not about to sacrifice his salary by retiring, so he continued to practice, now relegated to the scout team, but playing hard, covering, knocking down balls. When he was prevented from further participation in practice, even as a member of the scout team -- for being a "distraction," as he was told -- Herb, for the rest of the season, watched quietly from the sidelines. At the conclusion of the season, he retired. Again, quietly. With all the dignity he had exhibited as a player.

"Tom Landry had a bitterness in his heart for me," Herb remarked in a recent conversation. "After all I did for that team, I'll never understand it."

"Me either," I replied. But I wondered if Lombardi's psychology didn't hold a clue to the nature of those forces that had been working against Herb -- the "how" of them, anyway, if not the "why."

In one of the most compelling sections of his book, Maraniss examines Lombardi's contradictory relationship to pain. Evidently unable to tolerate the slightest physical discomfort in himself, Lombardi sought to exorcise that demon from his players, using as his instrument the Nutcracker Drill, over which he presided with glee. "It is characteristic of many leaders," writes Maraniss, "that they confront their own weaknesses indirectly, by working to eliminate them in others, strengthened in that effort by their intimate knowledge of frailty."

Perhaps Landry was also one of those leaders. Although he and Lombardi were antithetical personalities, perhaps Landry, too, acted indirectly. For Herb, as he departed, seemed to carry all the residual frustration of Landry's lifelong competition with Lombardi. That Herb had come to the team over Landry's objections exacerbated the situation. That Herb had been instrumental in Dallas' success dumped more salt in Tom's wound. As the personification of this seeping hole, Herb had to be humiliated, then dispatched. Some leaders, it seems, must purge to be purged.

Maraniss' insightful analysis forced me to think again about my nightmare. I came to realize that my fear, and submerged anger, was directed not just at any authority figure, but at precisely the kind of authority figure who worked out his own weaknesses on the bodies of others. Seen in this light, my refusal to participate in the drill was no act of cowardice, but rather an act of healthy resistance.

In fact, the Lombardi who haunted my dreams was a stand-in for someone else. After all, I didn't know Lombardi. Although he had possessed this trait in life, I had no way of knowing that. I had appropriated him to mask a more intimate figure, one who also embodied the trait. A larger force, who, at the time, I was unable to name. Old Dad, it seems, is never far from the scene. And it was Old Dad, not just Landry and what I imagined Lombardi to be, but my own dad, whom I had been carrying around on my back. It was a load far heavier than I should have allowed it to be.

Ironically, my father bore little resemblance to the squat, volatile Lombardi, but on more than one occasion he was confused for Landry on the street. Both men were tall, fair, square-jawed and handsome, with a Christian upbringing and a military bearing. My father became an Air Force general; Landry flew bombers in World War II. Trained as engineers, both men were analytical. Both made a virtue of losing their hair. But if they were physically dissimilar to Lombardi, my father and coach Landry did share one attribute with him: a need to create and mold an image of themselves out of their respective environments.

Perhaps this trait is also characteristic of a certain kind of leader. For Lombardi and Landry, the object of their desire was their football teams. Lombardi was very direct in stating his wishes, as Maraniss reports. And the Cowboys were quintessentially a team concerned with "image" -- an image, of course, that was a reflection of their leader, Landry. On the field, a technical failure to conform could lead to a chilling dismissal, as in the case of Herb. Off the field, there were similar consequences. I recall once quoting Nietzsche to a TV sports reporter on the subject of critics. The reporter, Tom Hedrick, wanted to know if the current criticism of the team was harmful to players. Citing my source, I said, "Critics don't bite for the sake of the sting, Tom. They bite because they need your blood." He laughed, but the next time I saw him, he told me that a club official had instructed him not to talk to me anymore, but to find somebody else more cooperative. "Nietzsche! That's not football! People don't want to hear that crap!"

Because my father wasn't a coach, this dynamic played out much closer to home. Not surprisingly, it had its origins in his own upbringing. My father's father was in his mid-50s when my dad was born, in his mid-60s when my dad approached puberty -- the time when many boys show their first serious interest in sports. A Yale-educated congregational minister, pursuing, at the age of 64, a Ph.D. at the University of Edinburgh in 1934, my grandfather was simply too preoccupied to spend time with my dad. Filling this paternal void was my grandfather's young missionary wife, who had her own ideas about what little boys should do and be. The photograph is still haunting: My dad and his brother, Ted, dressed up in satin and lace, two proper Victorians -- a pair of Little Lord Fauntleroys. They hated it. They hated the imposition of her ideal as much as they hated my grandfather's absence. This pathetic state of affairs, they vowed, would not be repeated when they had kids.

And so it wasn't. From an early age my dad was out in the yard with me, throwing balls. Baseballs. Footballs. Basketballs. It was fun. My brother, Tim, and I often went to a nearby vacant lot to slog through the mud of a crisp November day, hurling each other down, flinging passes through the deepening dusk on a field with no boundaries, in a game with no score. Those afternoons were exhilarating, unforgettable. Primal. Pure. But at some point a line was crossed. I was around 9 or 10, I guess, when my dad started the exercise sessions, in conjunction with our first sojourns into organized sports. Weights. Calisthenics. Regularly, whether my brother and I wanted to or not. The rationale was always present: "My dad never worked with me. Someday you'll thank me for this." Nicknames were invented for us. The sports fantasy was spun out, now with a particular emphasis on football, perhaps in reaction to my grandmother's general aversion to any sort of unrefined masculine expression.

My attitude to football was complicated. I discovered that I had talent, and I enjoyed playing. But also I knew that it was my dad's fantasy for us that was operative here, not our fantasy for ourselves. On some level, I felt my talent was being exploited, co-opted, by my dad. My own physical gifts, it seemed, no longer belonged to me. My solution was to sabotage that appealing part of myself. Or rather to do it sometimes. Because of course at other times it felt too damn good to succeed! It was a senseless, self-destructive bind, I knew. And I vowed, with as much conviction as my father had vowed it before me, that this pathetic state of affairs would not be repeated with my own children.

As the father of two boys, I was loath, as they grew up, to encourage them to play football. There were just too many coaches out there who were hell-bent on re-creating the world in their image, even if their world consisted of nothing more than a bunch of confused, snot-nosed 6-year-olds, whose deepest desire was simply to squat and dig in the dirt. Living in Texas, however, it was inevitable that my sons would discover the game, and so they did, in middle school, but on their own, without parental prodding.

"Dad, I love to cover kicks," said my younger son, John, as he prepared for his first college season several years later. That he could speak such a sentence was at first a shock. "John! My God!" He was such a sweet, sensitive child. A moon-child, as I always thought of him, because that was the first word he spoke. Not "Ma-ma," or "Da-da," but, pointing to the heavens, his face full of glee: "Moon!" And now he was telling me he loved to cover kicks? But then I realized that John's utterance meant that he appreciated the game at its purest level. That he knew its joy, as my brother and I had known its joy on that vacant lot so long ago. And it was gratifying to realize that he could still find the essence of a game that had transmogrified into a commercial circus. That he had not been hamstrung, as I had been hamstrung during my own career, by a debilitating, Landry-like self-consciousness. For my elder son, though, the game proved to be harrowing.

Seth is three years older than John, and as he grew up, he discovered soccer, a game he truly loved. "Soccer: the intelligent man's football" was a sticker on the bumper of his coach's car, and he often pointed it out as we left the field after a practice. But I got too involved with his participation in the sport. I was around too much. I was much too interested. Around the age of 9 or 10 I noticed in him my own tendency at that age to devalue his ability, to dismiss it as unworthy of pursuit. There was a scene after one game in which I excoriated him for failing to play up to his potential, for failing to focus, to concentrate -- to do, in other words, what I had never consistently done myself. I angrily implored him to "be a player."

Immediately, I realized my mistake and backed off. I decided to let him own his own experience of the sport, without me co-opting it. The strategy paid off, for very quickly Seth blossomed into a more than accomplished halfback. But had I gone too far? Was it already too late? Had I already implanted in him what had been implanted in me -- an image of "Dad" he could only hope to resist?

When, in middle school, Seth decided to go out for football, I was supportive, but, because of my own experience, deeply ambivalent about his decision. I kept my concerns to myself, however, until a Thursday afternoon late in September 1989, when the Hillcrest High School freshmen took the field to play the freshmen of neighboring A. Maceo Smith. Smith was a new high school then, with no varsity team, so older players were playing down -- juniors on the JV, sophomores with the frosh. But one player in particular appeared to be even more of a ringer than the Dallas Independent School District permitted.

"Boy, look at the size of that fullback," I remarked to my wife as we sat watching warm-ups. "If he hasn't voted in a presidential election, I'll kiss somebody's butt."

The player in question was huge, over 6 feet tall, weighing in excess of 225 pounds -- a man among boys, as a survey of our team quickly confirmed. Watching him, I got worried. "Somebody's going to get hurt."

In my nightmare of Lombardi I was pancaked in a Nutcracker Drill and refused to get up. Ironically, the Nutcracker Drill, though a powerful symbol, was next to worthless as training for a game, because of the unnatural constraints of the dummies and the lack of passing to keep players honest. Rarely, in a game, did such an isolated instance occur, but in this game, toward the end of the first quarter, one did. It was a reenactment of my deepest football fear -- but my son lived my nightmare.

A. Maceo Smith had the ball on the Hillcrest 20-yard line. An off-tackle play had been called, and once again the gargantuan fullback accepted the hand-off. But this time he was headed straight for 170-pound Seth, playing left defensive tackle. Seth had shed his block beautifully and was now crouched in the hole, poised for the hit, as the fullback bore down on him.

Physically, Seth was more than outmatched. He was an insect in the path of a bus. Part of me wanted him to turn away, to bail out, fall down -- anything to avoid the moment that was coming. But the other part of me demanded that he stand fast.

He didn't move. He stood his ground. "My God," I yelped, bolting to my feet, as the concussive BANG! of their collision rang through the empty stadium. Helmets went flying. "What a hit!" I bellowed, grabbing my wife. For an instant, I was as proud of Seth as a football parent could be.

Then my wife said, "He's not moving."

I peered at the field. The fullback had gotten groggily to his feet. But Seth was still down, unmoving. He was surrounded by players gesturing frantically for their coach. I ran onto the field.

Seth was numb all over. Taking no chances, the medical staff summoned an ambulance, positioned him on a board and loaded him up. Off we went, Seth a motionless lump, the paramedics checking vitals as we raced to the hospital.

Outside, it was a stunning autumn evening. The sky was big and blue. The first stars glimmered. I felt like I was going to throw up. Well, here you are, I thought. You're in an ambulance, racing to the hospital, your son numb on a board, groaning. Injured in a fucking football game. And he may never get up.

In the emergency room I watched as doctors carefully removed Seth's helmet, cut away his uniform, sliced off his shoulder pads. As one physician queried him, peering into his eyes with a penlight, a portable X-ray machine was wheeled into the room. Then a nurse asked me to step out, so that I would not be exposed to the radiation.

Outside, I wandered down the hallway, glancing into the various treatment rooms. A broken arm here, a gashed forehead there. Worried relations paced the floor. In the waiting room, I bought a soft drink, flopped down. Another ambulance was backing up to the door.

After a while the nurse reappeared and motioned me back. By this time, Seth had been moved to a holding room beside the main treatment area. A doctor met us at the door.

"Good news," he said. "The X-rays were negative."

"Thank God," I murmured.

"Seth's suffered a concussion, and some pinched nerves, and strained muscles in his neck. We've given him medication."

In the holding room, Seth was propped up in a hospital bed, his face flushed, his eyelids fluttering, as he dropped in and out of sleep. I settled down in a chair to wait. An hour later, as feeling returned to his arms and legs, he looked up, smiled.

"Dad, everything's tingling."

"Good," I murmured.

"Does that mean I'm all right?"

I nodded, told him the doctor's diagnosis. He sighed, reached for a glass of water.

"So what happened?" he asked.

"You mean on the play?"

"Yeah."

"It was a great hit, Seth," I said. "That big fullback, head-up in the hole -- it was like a cannon going off. One of the biggest hits I've ever seen."

Even as the words came out of my mouth, I regretted that what I was saying could sound like callous enthusiasm.

"Gee, thanks, Dad," he said, mockingly.

I helped Seth sit up then, grabbed his shoes. Although he was going to be all right, we both felt awful.

"You can quit now," I wanted to tell him. "As far as I'm concerned, you could never play another down."

But I couldn't bring myself to say it. No, it's his decision, I thought. He'll do the right thing.

And eventually he did. He quit. He quit not out of fear, or to spite me, but because he wanted to. He made his own decision. To my everlasting gratitude, he shed the spectre of demanding, judgmental, unpleasable coach. Maybe someday I'll be free of it myself.

Maybe. Someday.

Shares