One of the oddest recipes ever put in writing can be found in M.F.K. Fisher's book "Serve It Forth." It involves gently peeling tangerine sections -- "do not bruise them, as you watch soldiers pour past and past the corner and over the canal towards the watched Rhine" -- and placing them on newspaper atop a hot radiator. "Al comes home, you go to a long noon dinner in the brown dining-room, afterwards maybe you have a little nip of quetsch from the bottle on the armoire. Finally he goes. Of course you are sorry, but ... On the radiator the sections of tangerines have grown even plumper, hot and full. You carry them to the window, pull it open, and leave them for a few minutes on the packed snow of the sill. They are ready."

Of course, making Fisher's tangerine sections requires an old-fashioned steam radiator. But there are other components, just as essential: the soldiers, the Rhine, the snow on the windowsill and, most of all, Al. Without Al, the recipe will fail like a cake without eggs. The point is that a recipe broken down into a neat series of ingredients and procedures can never capture the thing that makes food memorable. Fisher, in her sly, elliptical way, is telling us: You had to be there. Our meals are always tied up with the rooms where we eat them, the people we share them with.

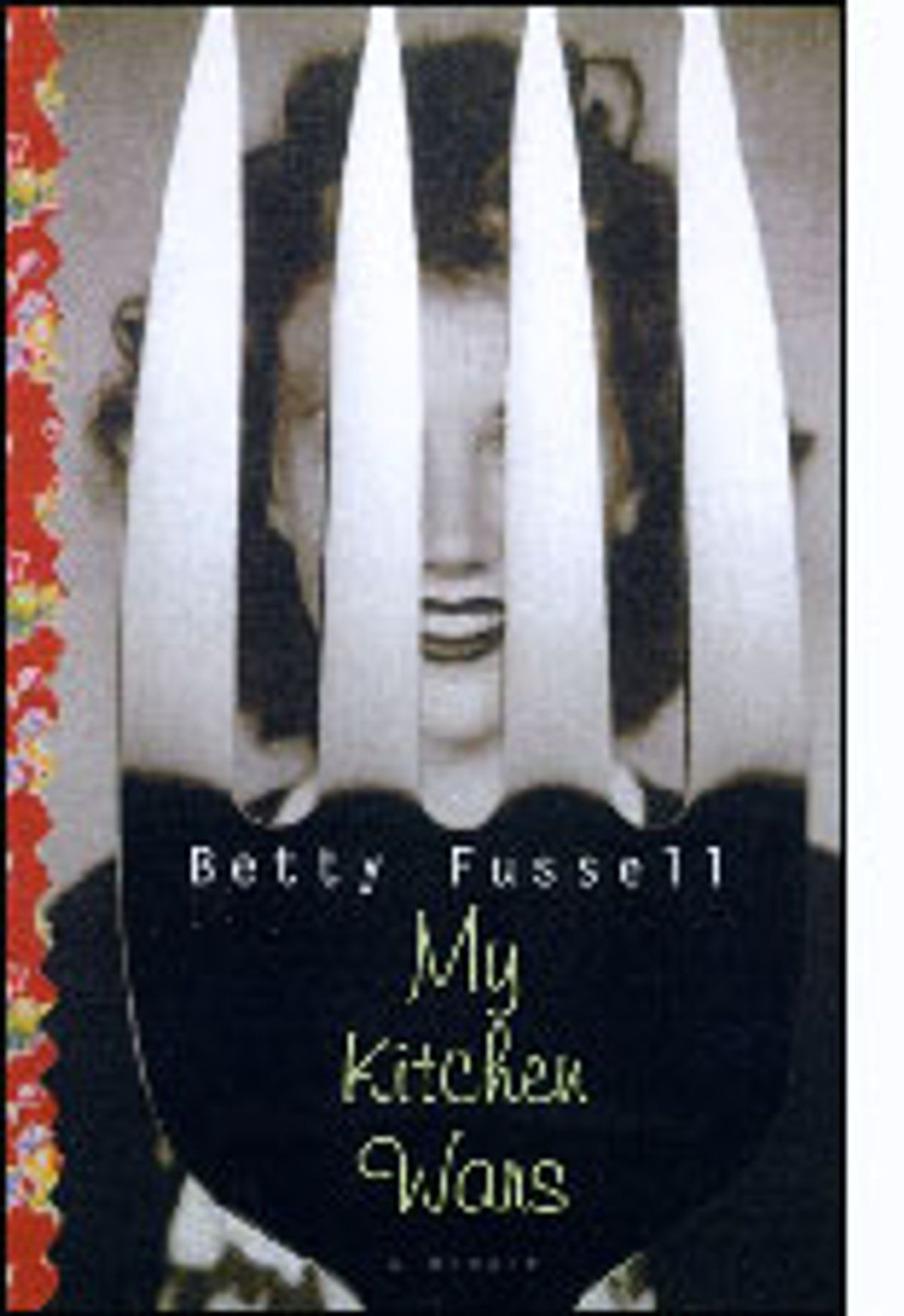

In her new memoir, "My Kitchen Wars," Betty Fussell, the cookbook author and food historian, recounts a lifetime's worth of eating and cooking, showing how closely her meals were bound with her life until the meals add up to an autobiography. There is a bleak, frontier-style upbringing in the orange groves of Southern California where, as a young toddler, she breaks into the icebox and eats an entire pound of butter before she is discovered. After her mother kills herself by dipping into an open tin of rat poison, Betty falls into the hands of a dreadful stepmother whose relationship with food is best described as adversarial: She steams all meals into submission with a pressure cooker and teaches young Betty to chew a full 50 times before swallowing.

At Pomona College, Betty discovers french fries and Coke. She also meets an aspiring writer, Paul Fussell, and when they marry she finds herself with a kitchen full of wedding presents. In learning to use those toasters and percolators and blenders, she becomes a new person: the '50s housewife.

Fussell wants to perform in the kitchen, but she is stuck with an unappreciative audience. One night she gets creative and throws some peanuts into the blender with her salad dressing. It would be years before Thai restaurants turned up across America, and Paul is not interested in being ahead of his time. "Salad dressing is one thing, peanuts are another," he tells her.

So she saves her inventions for dinner parties, which become ever more ambitious as the clam dip and Ritz crackers of the Betty Crocker years give way to the blanquette de veau and riz ` l'Impiratrice of the Julia Child era. Fussell's sardonic accounts of the changing fashions in the suburban dinner party are delightful bits of social history. As she and her friends fret over their ovens while their soufflis rise, or don't, a nation outgrows its provincialism. It was a watershed moment in the way Americans thought of themselves, and Fussell gets the significance, and the silliness, just right.

What she doesn't manage to convey is any real sense that food can bring pleasure. In her first chapter, she explains that she sees cooking and eating as brutal acts. "Hunger, like lust in action, is savage, extreme, rude, cruel." She chases her food-

For someone who has devoted her life to food, Fussell's insistence on seeing it as something negative and aggressive is strange, to say the least. The war trope leads her to some unusual insights, but it also keeps her from depicting any scenes of peace. After a while you start to wonder: Why did these people keep throwing parties and going out to dinner if they weren't enjoying it? The answer, you start to suspect, is that they did enjoy it, at least once in a while. Fussell just won't allow herself to say so. After all, war is hell.

War, though, does seem an apt word for life with Paul Fussell. An aesthete, an Anglophile ("like some nationalist transsexual, he felt he'd been born an Englishman in an American's body") and an ambitious academic, Paul made verbal jabs at his wife that didn't stop with her salad dressing. Even after he had won fame for such books as "The Great War and Modern Memory," he seemed to resent Betty's writing. When she lands her first book contract, he opens a bottle of champagne but then stops short. "My God," he says, "I'd better get upstairs and get cracking."

Writing about her marriage, Fussell never finds the tone of bemused detachment that lets her laugh at her attempts to stage eight-course dinners that would have capsized a professional kitchen. Her anger is still fresh two decades later as she exhumes private moments and thrusts them into the light. Her readers hear about the time she caught Paul naked in the library with a young man he was teaching at Princeton. We learn that her sessions with her lover usually took place outdoors and that one afternoon in Italy the two of them got up and discovered that they had been rolling in a pile of goat shit.

Opening her photo album to the page where she keeps these special Kodak moments, Fussell might say, is simple honesty. But there is honesty and there is truthfulness. A truthful account of most 30-year marriages would include ugly, degrading moments, but it would also reflect some that weren't so bad. You know you're finally over a lousy relationship when you can admit that once in a while you and the creep had some fun. Betty Fussell remembers her creep as someone who was creepy all the time.

Who would want to write a memoir of a lifetime of ruined meals? More to the point, who would want to read it? Fussell has tried to serve up something fresh and original, but her appetite for revenge poisons the effort. It seeps all through this memoir, leaving a taint of bitterness that won't go away.

Shares