Picture this: A photo of a boy and girl -- unmistakably naked, posed and giggling -- holding two very large sausages (Italian?). The boy is maybe 8, the girl maybe 6. They are not touching each another, nor does the camera seem especially interested in their genitals. What catches the eye are those sausages, but not that they are involved in anything you or I would call, right off, sexual: They are not being licked, stroked or inserted. They are more atmospheric, I guess you could say.

Is this child pornography? Well, if you are a photo lab manager in Burbank, Calif., you follow the in-store policy and ask the store manager. The store manager, noticing the nudity and the meat, follows what he takes to be the law and calls the Burbank police. The police send two undercover cops out with instructions to nab the photographer. The cops then order the photo lab manager to phone the customer, tell him his prints are ready and instruct him to come pick them up right away.

The customer agrees to drop everything and run over, but then doesn't show, forcing the undercover police to cool their heels for six hours before giving up. Later the cops do nab the suspect, who says the photos were taken by the kids' uncle who thought the children's play with the sausages was "funny." The Burbank police decide to let it go with a warning laced with disgust: There's nothing "funny" about photos like these, photos that are indecent, degenerate and, next time, criminal.

As a script written for the Keystone Kops, this much ado about sausages scenario would be funny. But it is a true story. It is a sorry saga about our confused desires when it comes to kids and sex, and the way these collective desires are reflected in our failure to clearly define and execute the laws governing child pornography. This black comedy set in Burbank proves a scary point: At this time there is no way to differentiate -- legally -- between a family snapshot of a naked child and child pornography.

Not that photo labs don't try. They do, and every now and then they light upon (or concoct) what they take to be a case of child pornography. There are about 10 cases in the last dozen years that have emerged in the press. Some are worthy of mention here, mostly because they weren't worthy of attention when they occurred:

- William Kelly was arrested in Maryland in 1987 after dropping off a roll of film that included shots his 10-year-old daughter and younger children had taken of each other nude.

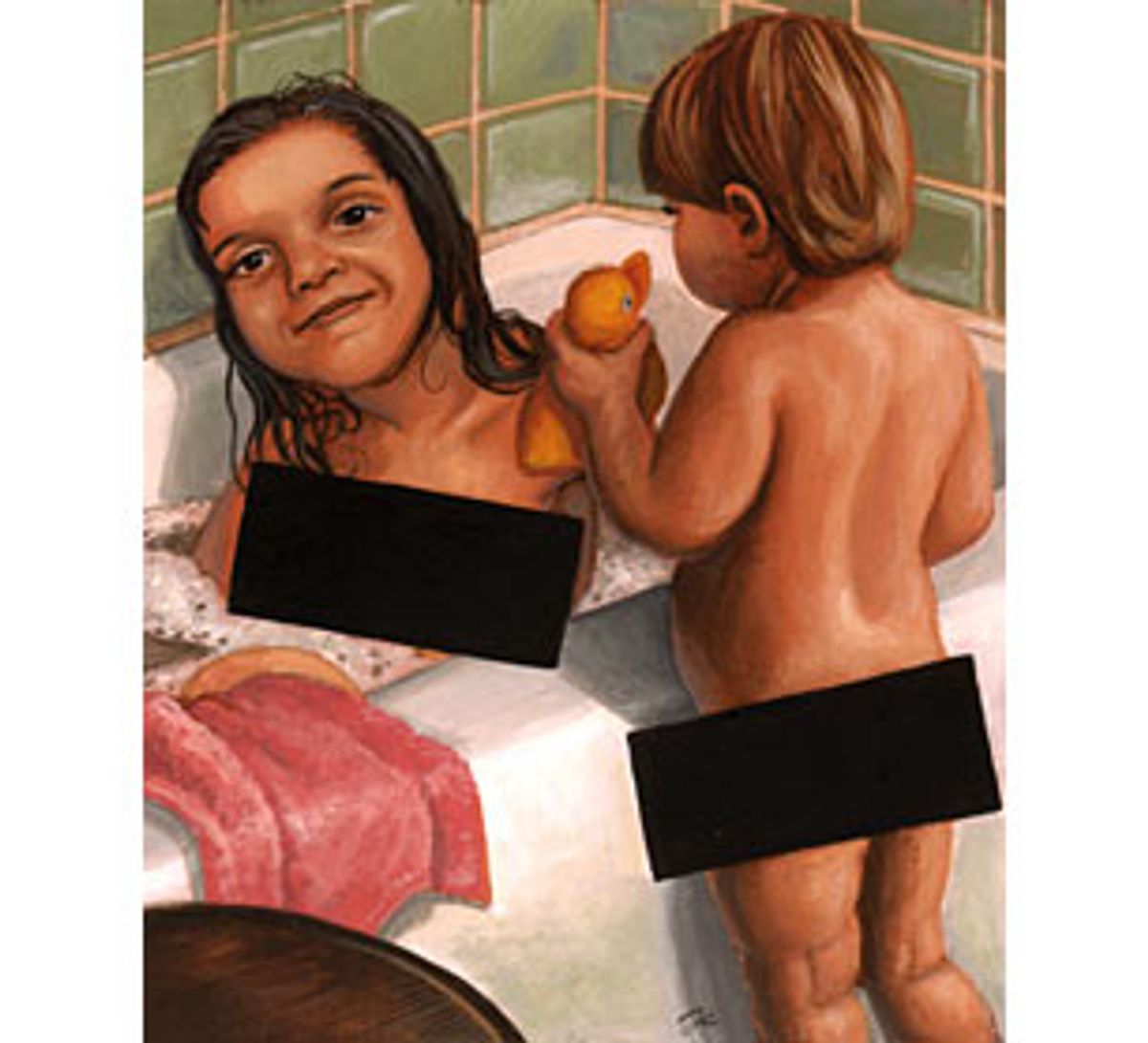

- David Urban in 1989 took photos of his wife and 15-month-old grandson, both nude, as she was giving him a bath. Kmart turned him in and he was convicted by a Missouri court (later overturned).

- A gay adult couple in Florida decided to shave their bodies and snap their lovemaking, convincing a Walgreens clerk that one of them was a child. They are suing the Fort Lauderdale police.

- More recently, Cynthia Stewart turned in bath-time pictures of her 8-year-old daughter to a Fuji film processing lab in Oberlin, Ohio. The lab contacted the local police, who found the pictures "over the line" and arrested the mother for, among other things, snapping in the same frame with her daughter a showerhead, which the prosecution apparently planned to relate somehow to hints of masturbation.

Even though the number of arrests is not large and the circumstances seem ridiculous, this photo lab idiocy is a serious matter: It puts all of us at risk, and it significantly erodes free speech protection by insisting that a photograph of a child is tantamount to molestation. Since it is what is outside the frame (the intention of the photographer, the reaction of the viewer) that counts legally, we are actually encouraged to fantasize an action in order to determine whether or not this is child pornography.

Every photo must pass this test: Can we create a sexual fantasy that includes it? Such directives seem an efficient means for manufacturing a whole nation of pedophiles.

The laws, whether state or federal, are inevitably firm-jawed when it comes to meting out punishment to child pornographers. But they seem uncertain both in what it is they want to put an end to and how far they want to reach into our home photo albums to do it.

In the great sausage caper, the photo lab operator and the Burbank police acted as our representatives to decide whether pictures of children and sausages constitute child pornography. This suggests that they have a clear idea of what a child is and that they know porn when they see it. What this also means is that we have a system that allows criminal conduct to be determined by just about anybody.

So, how do I know which kid pictures I can take to Wal-Mart, and how does the Wal-Mart photo guy know when to call the police about my pictures? The short answer is that there is no way I can know because there is no way he can know.

Some states require that photo labs report any photo that they deem suspicious to the police while others do not, but none give much help in explaining what suspicious photos of children actually look like. State law on child pornography is murky at best, and it varies from state to state. And when a photo lab sends its material to another state for developing, federal laws (which may differ from the state laws, but are equally murky) come into play.

In the absence of clear jurisdictional authority, much less clear laws, anyone snapping pictures of kids and wanting to avoid the slammer might decide to simply ask about the policies of their local labs and the corporations that direct them. How do they separate those who are simply charmed by their naked kids from those who seek to charm others for profit?

I expended no little energy trying to unearth the guidelines from the corporate headquarters of photo developing giants. I may as well have tried to get to the bottom of Cosa Nostra rub-out policies by making a few calls. I did discover that the world of photo developing is surprisingly small and, perhaps not so surprisingly, secretive.

When one talks to people at the top, as I did, one finds a penetrating and pervasive fear of public exposure. My sources promised to speak only on guarantee of anonymity. Too many lawsuits are pending and too many threats of others simmer to allow policy issues to be made public, said a top lawyer at one of the nation's largest photo developing companies.

Still, according to all my sources (which include executives on the corporate level and also five local photo-lab people incautious enough to spill the beans), the correct procedures for handling questionable photographs are never clear and they vary -- even within the same corporation -- according to state law. They do not pertain to erotic pictures of adults unless they appear to depict rape or some other illegal activity. (Or unless one of the adults could be mistaken for a child.)

Kids are different. Naked kids under the age of 5 or 6 are probably OK, so long as nothing else in the picture invites suspicion. Nudity in older children may be a problem -- or maybe not. It is up to the lab person or a supervisor to consult his or her own sense of propriety and moral sensitivities, as well as any rough-and-ready training that has been given in how to determine whether a photo constitutes child pornography.

Actually, given that the focus of the law has shifted from the photo to the reaction of the viewer, the wise technician will consult his or her loins: A turn-on means porn.

In any case, it seems obvious that only a society under great stress, wanting to look at kids' bodies and blame it on somebody else, would tolerate dissemination of its policing functions to photo development clerks. We put photo labs in the position of resolving a massive cultural confusion that is both vicious and duplicitous.

No one, of course, is allowed to say that improper snapshots are not a problem -- much less that child pornography in all forms is nothing but an urban legend. Nevertheless, according to state police officials in California, there is no commercially produced child pornography in this country and hasn't been for some time. The risks of making it, they say, are simply too great.

Several speakers at an L.A. police seminar I attended a few years back laughingly admitted that the largest collection of child porn in the country is in the hands of cops, who edit and publish it in sting operations. There is at most, they say, a small cottage industry among civilians in which pictures (most of them vintage) are traded.

Even so, one might argue that amateurs are pros-in-the-making and that the problem of distribution is not solved by such a distinction. But as Philip Stokes, a photographer and senior research fellow at Nottingham Trent University, points out, although it may be true that somebody guilty of assault on a child has nude photos of children, that does not allow us to reverse the argument and say that possession of such photos means someone is contemplating the act. One might as well assume, he says, that anyone possessing antique magazines is on the road to burglary.

The truth is that true research in this area is impossible, given that it's illegal to look at anything that is or might be child pornography. As a result, nobody knows exactly what child pornography is, what forms it takes, where it is, how much of it exists -- or even if it exists. We seem happy that nobody knows: That way we can take our fantasies, project them onto phantom demons (the child pornographers) and feel righteous.

As for kiddie porn developed by mainstream photo labs, I would bet that it hardly exists at all. Oh sure, you may be able to find a case or two, but, allowing for a certain hyperbole on my part, I would say that we are off on another loud ride into fairyland, duplicating our earlier trips into satanic ritual abuse and recovered memory accusations.

We know that kids are not harmed by family snapshots or any other kind of photography this side of snuff films and photographs that document actual cases of assault, rape and other forms of violent coercion. So when was it, exactly, that the law lost the ability to tell the difference between a family snapshot and kiddie porn?

The latest wave of confusion comes from two developments in the '80s and early '90s: New laws were passed to differentiate child porn from unapologetic adult hardcore porn, and a new philosophy of pornography emerged that insisted that a potentially lurid photo can be considered not just illegal but a criminal assault on its subject.

We owe the latter assertion to the lamentably influential anti-porn feminists Catherine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin. They argued that porn (originally adult heterosexual porn) constituted not just image but action -- action identical to sexual assault that is repeated each time the photo is distributed or viewed. (They did not, however, bother to define "pornography"; they assumed we all knew it when we saw it, which, in turn, ensured that we could never really know when we were not seeing it.)

Child protection experts used these arguments to redefine activities that looked vaguely pedophilic as criminal actions. Child pornography became tantamount to murder. Lloyd Martin, the infamous LAPD officer who was considered a national expert on the dangers to children throughout the '80s, popularized the equation. Any form of pedophilic activity, he announced, is "worse than homicide."

I think I'd rather my uncle take a picture of me with any number of sausages than kill me, but the real question is: Why would we make such comparisons? Why does a nude kid with a sausage make us think of murder? What leads us to feel that family photos of naked kids might demand attention? What are we criminalizing? What are we protecting? Can't we tell the difference between a photo and an action? Even if the photos seem, to some people and to some degree, erotic, so what? Can't we sense the erotic without acting on it? Why do we pretend that photo lab operators and cops are experts in the interpretation of images and the erotic impulses of those who record them and those who look at them?

The law provides no answers. In fact, we have made the key terms in operative legal statutes so vague that we can hardly be certain that any photo is clearly pornographic or, more to the point, not pornographic.

In 1982 (N.Y. vs. Ferber), child pornography, as yet undefined, was declared

to have no artistic significance and to be indefensible on those grounds.

In 1984, child pornography was, for the first time, distinguished from adult

pornography in federal law and defined as the "lascivious exhibition of genitals" in an underage subject.

By 1989 (Mass. vs. Oakes), "nudity with lascivious intent" was added to the definition. (All of this, I should add, is a part of federal law, which comes into play only in cases of interstate activity. Otherwise it functions as no more than a set of suggestions for state laws, which vary widely and wildly.)

The inclusion of "intent" shifted attention from the photo itself to the motives of the photographer and even the receiver of the photo. As a result, more laws were needed to list the elements that might provide clues to the photographer's intentions. Now such things as a "visually suggestive setting or pose," "inappropriate attire considering the child's age," a suggestion of "sexual coyness," an intent "to elicit sexual response in viewer" or the use of a photo, regardless of the photographer's intent, are specified "factors" in making the determination as to whether or not a picture of a child can be considered pornographic.

And that's not all. The subject need not be naked for a photograph to qualify as child pornography. In 1994, Janet Reno decreed: "Neither nudity or [sic] discernability of genitals through clothing is a required element of the offense." It is also not clear whether child pornography needs to involve actual children. If the photo conveys the impression that a child is involved in lascivious photos, that may be good enough. So morphed and simulated photos may still be judged to have a devastating "secondary effect" by stimulating the public appetite for such photos.

The law leaves us in a fog surrounded by murk enveloped in blackness. Sometimes adults who look like kids are photographed lasciviously. Other times, what are clearly kids are pictured in what some regard as lascivious attire. New York Mayor Rudy Guiliani and many others were deeply shocked by a proposed Times Square billboard showing small boys in expensive underpants bouncing on a suitably expensive couch. He thought it might encourage lascivious thoughts -- not in him but in pedophiles. Calvin Klein backed down and allowed the furor to give him the publicity the billboards were aimed at.

Makes one wonder. What would it take to produce a picture of a child that was indubitably not pornographic? Put another way, why do we declare some things innocent and some criminal, some cute and others disgusting?

Consider this: Within the same cultural climate that sees sausages, showerheads and sofas as erotic props, "Naked Babies," a book of photographs of the same by Nick Kelsh with text by Anna Quindlen, is not just acceptable -- it's in its second printing. Quindlen's prose -- full of treacle and truism, bathos and balderdash -- provides a sentimental counterpoint that negates any suspicions aroused by Kelsh's rain of naked bodies: "Adults in the presence of a naked baby reach out their hands," she oozes, "as though to warm themselves at the fire of perfection."

But how exactly is it that nakedness is divine at one point and the desire to touch it an act of flat-out reverence when, a few years later on in the child's life, nakedness becomes shameful and any adults reaching out hands to warm themselves at the fire of perfection will find themselves in manacles? According to Quindlen, a naked baby is "androgynous," "sensual as anything but not sexual at all," while "a boy, a girl -- well, they are something else."

I agree that children are at risk -- but not from cameras. Children are put at risk by neglect, emotional and physical abuse, bad health care, lousy education, lack of hope. Even sexual abuse, which ranks low among their torments, is not a problem of stranger abductions, child pornographers, priests or scout masters; it's a family problem. And we all know that. It's so well-known it can, it seems, be ignored.

Even sexual abuse, though it commands our attention, is not, statistically, a highly significant form of child abuse. The National Committee to Prevent Child Abuse reports that 11 percent of reports to child protective agencies involve sexual abuse (a little higher than "other"), far below physical abuse (30 percent) and neglect (47 percent).

One almost wishes that what we call "abuse" were the only nightmare kids have to face. For instance, 500,000 kids a year are classified as "throwaways" by the FBI. They are not foster children nor runaways (there are even more of those), but kids who really are set adrift, kids who would like to stay somewhere if someone would let them. But nobody will.

And yet we hurl our outrage and our resources and our art-critic police headlong into solving the non-problem of improper snapshots. It's a little like starting a campaign for flossing in the midst of the Black Death.

Our alarm at abuse through camera lenses is a clear instance of the way we substitute a trivial problem for a perilous one. It is also a clear instance of the confusion that drives us to do just that. We seem so obsessed by the need to distinguish sharply between kids and eroticism that we inevitably stir them together; meaning to put them in separate rooms, we provide secret passageways so they can visit. We say so often and loudly that there's nothing erotic about kids that we cement the association.

We are so obsessed by the bodies of children and are so devoted to protecting those bodies that we construct a world where very nearly everyone (but us) is driven wild by the sight of a child. Though we treat people who are sexually aroused by children as monsters possessed by feelings altogether unknown to the rest of us, we also act as if they were everywhere.

We like to say that the child pornography business is enormous, a multibillion-dollar industry; that the Internet is crawling with pedophiles distributing kiddie porn as they go; that millions of children are sexually molested by adults.

At the same time, we act as though these predators are not of us, are none of us, are as unknowable and rare as werewolves. Pedophiles are everywhere and nowhere, common and freakish; above all, they act as scapegoats for our own confused desires. We enter into heated mock battles with them at the oddest places: day-care centers, Satanic sites, schoolrooms and now photo labs.

We would not find ourselves in the midst of such a collective mess if we did not, on many levels, collectively want to be there. We all gain from sideshows like photo lab stings. And what we gain is immunity from thinking our own feelings. If we blame others loudly enough, we need not look at our own hearts and desires. It is a Gothic world we create with simple villains (the pedophiles) and equally simple rescuers (us).

Jock Sturges, the art photographer who has spent years in court for his photographs of children, analyzes all this very clearly for us: "I had to pretend to be something that, quite frankly, I'm probably not, which is a lily-white, absolutely artistically pure human being. In fact, I don't believe I'm guilty of any crimes, but I've always been drawn to and fascinated by physical, sexual and psychological change, and there's an erotic aspect to that. It would be disingenuous of me to say there wasn't."

So shines an honest man in a weary world. We all should be drawn to and fascinated by the beautiful and the arresting, including beautiful and arresting children, without being terrified by the erotic aspect in our fascination. Admitting to an erotic attraction is not the same thing as admitting to rape or assault: We do not commonly attack what we love and we do not feel the need to act on every impulse. Finding something erotic does not drive us irresistibly to mount it. We could use more complexity in our thinking on this subject, more tolerance for difficulty. And a lot more honesty.

The price we allow our children to pay for our scapegoating cowardice is enormous. Our kids, caught in the middle of all this, don't mind our snapping lenses, but they do mind the ghastly world we picture for them. It is a world filled with dangers around every curve, with safety only in non-pedophilic adults and our friends, the police. We ought to examine more searchingly if we are really doing all this for their good, if we really need to see the world this way, if we aren't the ones afraid of the demons. Especially the demons inside us.

Shares