In his 1924 "Studies in Classic American Literature," D.H. Lawrence noted that the American Indian was a baleful presence in the guilt-ridden American subconscious. "At present," he wrote, "the demon of the place and the unappeased ghosts of the dead Indians act within the unconscious or under-conscious soul of the white American, causing the great American grouch, the Orestes-like frenzy of restlessness in the Yankee soul, the inner malaise which amounts to madness, sometimes."

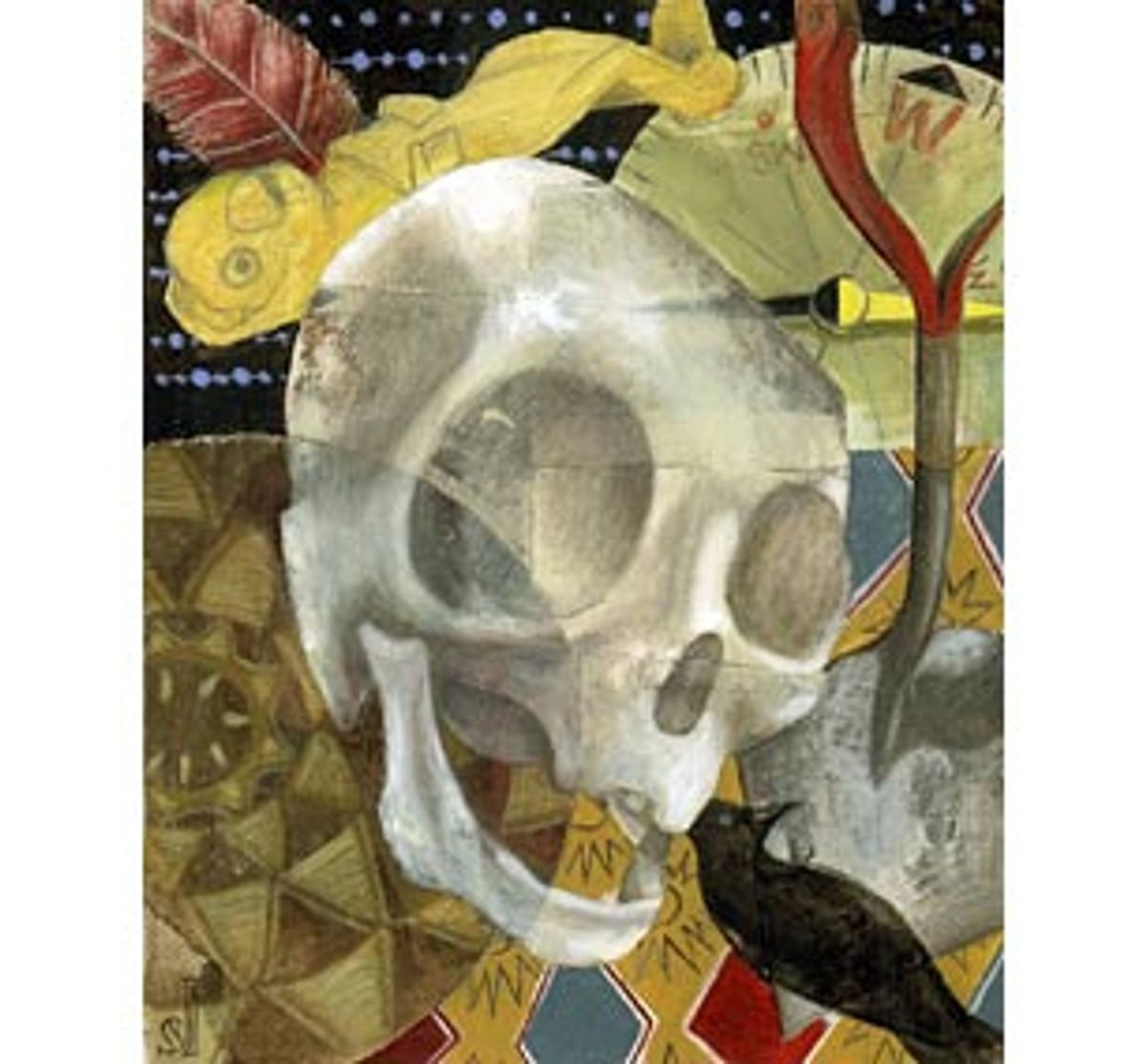

Eighty years on, the grouch has not lessened, and the hysteria is still at boiling point. Witness the bitter controversy over the recent discovery of so-called Kennewick Man. On July 26, 1996, two young men stumbled on a human skull in the Columbia River in Kennewick, Wash. Local coroner Floyd Johnson called in a forensic archaeologist and expert in human remains, James C. Chatters, to make an identification of the excellently preserved remains.

With permission from the Walla Walla district Corps of Engineers, which oversees the site, Chatters recovered a human skeleton which he characterized as having "caucasoid traits." He assumed, therefore, that it must be a 19th century cadaver. Not so: Radio-carbon dating established an age of at least 9,000 years. The tall, middle-aged man who had come to grief in Kennewick nine millennia ago was not, according to Chatters, typically Native American. Then who was he? Was he possibly not Native American? "Lack of head flattening," Chatters coolly noted, "from cradle board use." Was he "white"?

The media jumped on board at once. Had early Europeans, they asked, preceded even the Vikings into the New World by thousands of years? Antagonisms arose between the scientific community and the alliance of five tribes who claim the body as a violated ancestor -- the Umatilla, Yakima, Nez Perci, Wanapum and Colville. Examine the remains for DNA, cried the scientists; bury our sacred ancestor, cried the Five Tribes. "All we're asking for," said one Five Tribes member, "is a little common decency." The grouch suddenly sprang to life again.

Nor were things helped much when Chatters made a reconstruction of Kennewick Man's face. Lo and behold, he was the spitting image of "Star Trek's" Jean-Luc Picard. "He could also pass for my father-in-law," mused Chatters diffidently. "Who happens to be Scandinavian." The Five Tribes were not amused.

Now into this murky and emotional fray steps David Hurst Thomas, a curator of anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and a founding trustee of the National Museum of the American Indian. His new book, "Skull Wars," purports to be a history of the Kennewick lawsuit as well as a broad overview of the "deteriorating relationship" between archaeologists and Native Americans.

The book is prefaced by the noted Indian activist Vine Deloria, author of the gung-ho jeremiad "Custer Died for Your Sins," who is also neatly enough accorded a chapter in Thomas' book. The latter, notes Deloria, filled him "with incandescent rage." In his own book, Deloria sneered at white anthropologists as "anthros" and portrayed them as grim, hypocritical, imperialist exploiters. It is a dull caricature that Thomas himself enthusiastically endorses.

Thomas is nimble and well-read, and the bibliography betrays a mind that is curious and wide-ranging. I was pleased, for example, to see there the excellent David Henige of the University of Wisconsin, who has written brilliantly on modern misinterpretations of Columbus. Would, however, that Thomas had some of Henige's serious scholarly commitment to carefully worked insight and masterful intellectual narrative.

Although "Skull Wars" offers entertaining thumbnail sketches aplenty of American anthropologists like Franz Boas and Lewis Henry Morgan, the book is little more than a journalistic political tract designed to arouse the aforementioned "incandescent rage." In a series of rather rambling mini-essays we range with groaning predictability over every white-Amerindian grievance of the past 500 years, from Columbus and accusations of cannibalism to Red Power at Alcatraz. Foggy p.c. buzzwords such as "mainstream society," usually undefined, litter almost every page. And the loosely jumbled chapters somehow never accumulate any real continuity or vertical depth. In short, "Skull Wars" creates a curious texture in which sometimes interesting details (especially gossipy accounts of archaeological infighting ) are swamped by the vulgar and piously sermonizing mind of the activist. It is an all-too-familiar spectacle with American academics.

Thomas no doubt thinks that by devoting his first 100 pages to a kind of miscellaneous, potted History 101 account of post-conquest injustices that we will be better informed as to the cultural background to the Kennewick controversy. This is both patronizing and ludicrous. At one point he tells us that it was because the Greeks had a well-defined sense of "barbarians" that later Europeans decided to be unpleasant to Native Americans -- as if every culture in world history didn't also have similar notions of inferior outsiders. (The Ancient Mexica -- the correct term for the Aztecs -- for example, flatly called those living north of the Rio Grande "barbarians.")

But of course Thomas wishes to grandiosely string together Aristotle, the Conquistadors, poor old Columbus, Buffalo Bill, American anthropologists of the 19th century (fearful racists, needless to say), Manifest Destiny, the "termination" reservation reforms of the Eisenhower years and Kennewick Man into one seamlessly awesome tale of woe and infamy. They are all avatars, you see, of wicked "mainstream society."

The idea, bluntly put, is to imply that a branch of knowledge, in this case anthropology, is the slavish handmaid of conquest and unconsciously or consciously reflects its inner dynamic: standard neo-Marxist stuff. "The lingering issues between Indians and archaeologists," writes Thomas, "are political, a struggle for control of American Indian history." So there we have it.

We are therefore treated to numerous examples of American anthropologists pillaging tomb sites, hauling Native American artifacts into museums and generally displaying their brutish prejudices at every turn. True, Thomas also shows us the surpassingly liberal inclinations of a man like Boas while grudgingly admitting that it hasn't been all bad. But in general the men who created American anthropology are viewed as "anthros" -- white supremacists in mortar boards. We are then breezily told that "the American academic community -- led by grave-digging archaeologists -- has robbed the Native American people of their history and their dignity."

This is, of course, a fairly silly calumny. One wonders if the Egyptians or the Greeks, too, feel that their "history and dignity" have been abnegated by "grave-digging archaeologists"? Now, it is true that the former often wish the return of antiquities plundered by Indiana Jones-style 19th century archaeologists like Luigi Belzoni or the repulsive Lord Elgin. But they also acknowledge that these same early "grave diggers" were creatures of their time and often the very people who lifted ancient cultures out of oblivion.

Whether we like it or not, Egyptology began with Napoleon's invasion of Egypt: Before that, Ancient Egypt had been more or less forgotten. Is Egyptology, therefore, a creation of imperialism? Of course it is. Is it therefore "imperialist" in nature? Hardly. One thing does not necessarily entail the other, and Egyptians themselves have embraced Western scientific Egyptology with passion -- for what else is there? Knowledge is never a pure commodity.

On the other hand, it might be countered that the conquest of the Americas was unique in many ways, and that it has unleashed uniquely painful pathologies and racial distrusts. The Egyptians, one could say, are not a conquered people. (Actually, they are, since the Arabs were imperialists not indigenous to Egypt.) One could also argue that, because Indians have failed to achieve much in the way of tangible concessions from any Western society, their academic champions resort to hit-and-miss intellectual guerrilla war instead.

Nor, for that matter, can one really blame Indians for hating the powerful civilization that overwhelmed them. As Lawrence pointed out, dispossession and extermination do not exactly improve one's mood. What, in any case, is the Indian supposed to feel but distrust? Gratitude for affordable electricity?

But condemning whole intellectual disciplines as a way of "healing" these bitter divides is a cheap gambit as best. In much the same way, Martin Bernal tried this spin on the 19th century classicists in his polemic "Black Athena," crudely trying to represent the massive, groundbreaking scholarship of that era as a conspiracy allied to colonialism. Bernal's amateurish exaggerations, dubious linguistic conjectures and hyperbole eventually cost him dearly when he was painstakingly unravelled by the Wellesley classicist Mary Lefkowitz in her devastating "Not Out of Africa." Modishly insulting a few 19th century scholars, Lefkowitz showed, not only misrepresented many of them but also embarrassingly highlighted Bernal's own grindingly parochial political agenda. Their scholarship, in other words, was largely more professional than his -- but then again, most of Bernal's readers had never read the originals.

There are two critical questions relative to Kennewick Man, however, that Thomas does try to tackle with a minimum of politically correct rhetoric. The first is the possible relation between the ancient Neolithic American Clovis culture that flourished around 7,000-8,000 B.C., and a European equivalent, the Solutrean culture of the Slavic region and the Ukraine. As Thomas acknowledges, there are extraordinary similarities in tool-making technologies between these two cultures, while, surprisingly, none exist between Clovis and the equivalent Neolithics of northeast Asia, where Native Americans are supposed to have originated.

This is an intriguing avenue of speculation and an exciting frontier in North American archaeology, though not one that Native Americans themselves seem to feel very keen about. Surely, one would think, there is room for a reasonable examination of the Kennewick remains in the light of this evolving line of inquiry? Europeans could well have migrated across the subpolar tundra into the Americas or even taken boats.

Thomas seems to agree. But, disappointingly, he devotes little space to this fascinating issue and wafflingly concludes only that ancient America was "the original melting-pot." (Which part of the world was not a "melting pot"?) Why, the reader asks in frustration, are there only three pages about this possible provenance of Kennewick Man (not a certainty by any means, but a viable possibility) -- the same amount as are devoted to squabbles about the name of the Washington Redskins, the American Indian Movement of the '70s, the Boston Tea Party and Indian Olympic athlete Jim Thorpe?

The other critical issue is the antagonism between oral history and Western science. "The Kennewick controversy," writes Thomas, "highlights yet another serious conflict in interpreting ... criteria of 'a preponderance of the evidence.'" And he goes on: "Here, then, is the nub of the conflict: What are the relative merits of evidence about the past?" In other words, are oral tribal traditions and science reconcilable? It's a good question.

It's also one that should have been the intricate heart of this book, and to some extent Thomas does give it its due. But by simply urging reconciliation and sensitivity between Indians and scientists, he underestimates the profundity of the rift. In some ways it is unbridgeable. He quotes lawyer Alan Schneider, who worries that in certain instances the rest of America will be obliged to follow tribal historical lore when contemplating this continent's remote past. Even though Thomas argues that Indians are not necessarily against scientific examination of human remains, which I'm sure is true, I would say that this is a legitimate fear. If, for example, the Kennewick remains are reburied without being submitted to serious and accountable analysis, then the tale they might tell us is effectively silenced. Potential knowledge is reburied with them.

For his part, Thomas tries to paper over the cracks in his plan by overestimating the precision of the oral tradition itself. He claims that archaeology has been "humanized" in recent years on account of its learning to use "an entirely different history" -- the oral lore of Indian people themselves. "Most Indian tribes," he asserts, "maintain rich oral traditions, which describe in detail their remote past."

But there are deep problems with this. In the first place, what actually does "oral history" tell us about the Neolithic period? The answer is practically nothing. Indeed, oral history tells us almost nothing even about the Middle Ages, let alone about societies living 10,000 years ago. When African historians tried to reconstruct the notable 14th century East African kingdom of Great Zimbabwe through oral histories, for example, they ended up with the names of 12 kings and two battles. Everything else was lost, including the culture's actual name -- let alone things like its language, currency, diplomacy, etc. What "rich details" about American life 10,000 years ago, then, is Thomas talking about? We would love to know. Oral history is not, in fact, an "alternative way of knowing" the Neolithic age. At best, it might be a form of poetic collective memory, profound and often beautiful, but providing no "rich details" on the historical plane.

Secondly, however much traditional historians and anthropologists might be willing to work with oral historians, the accommodation is not returned; the Umatilla do not recognize the validity of scientific interpretations of Kennewick. To the contrary, they flatly reject them and insist that they know best. "From our oral histories," says tribal member Armand Minthorn bluntly, "we know that our people have been part of the land since the beginning of time." So that's that.

In the end, trying to make tribal lore and science equivalent ends up being a very tricky act. Witness Deloria, cavalierly dismissing radiocarbon dating and scorning scientists vastly more knowledgeable than himself as "incredibly timid people" crippled by a worship of orthodoxy. He also insists that mammoths were around at the time of the Pilgrims -- more oral history? -- and wonders if the Vikings, whom he calls "the premier explorers of the Christian era," really came to America at all. (The Vikings were, of course, militant pagans infamous for their violence toward Christians and were certainly not greater explorers than the Portuguese.)

Thomas himself tries desperately to navigate a sensible course through this pseudo-intellectual twaddle. Noting that Deloria has rejected evolutionary theory as well, he muses: "These are strange bedfellows: Native American communities, right-wing Christian groups and left-wingers. It is just this curious coalition that was instrumental in the passage of reburial legislation by the U.S. Congress."

Exactly. And scientists are justifiably outraged. For what was really at stake in that decision was not the freedom of Native Americans to adhere to their beliefs about the prehistoric past, which are not being denied, but the ability of this society in general to reflect rationally upon that same past without having to genuflect unduly to the above-mentioned groups, none of whom has any monopoly on the truth. In this instance, I would argue, it is not the anthropologists or archaeologists who are being the intellectual obscurantists. And why, it should be explained, is anyone's "identity" threatened by that same truth, whatever it may be?

In the end, "Skull Wars" cannot possibly resolve these impasses. It is simply an overheated work of protest. We can always bemoan, too, the fact that scientists are not more like the enlightened, cosmically multi-culti Jean-Luc Picard. But at the end of the day they have more to tell us about the past than anyone else. The rest is largely grouch.

Shares