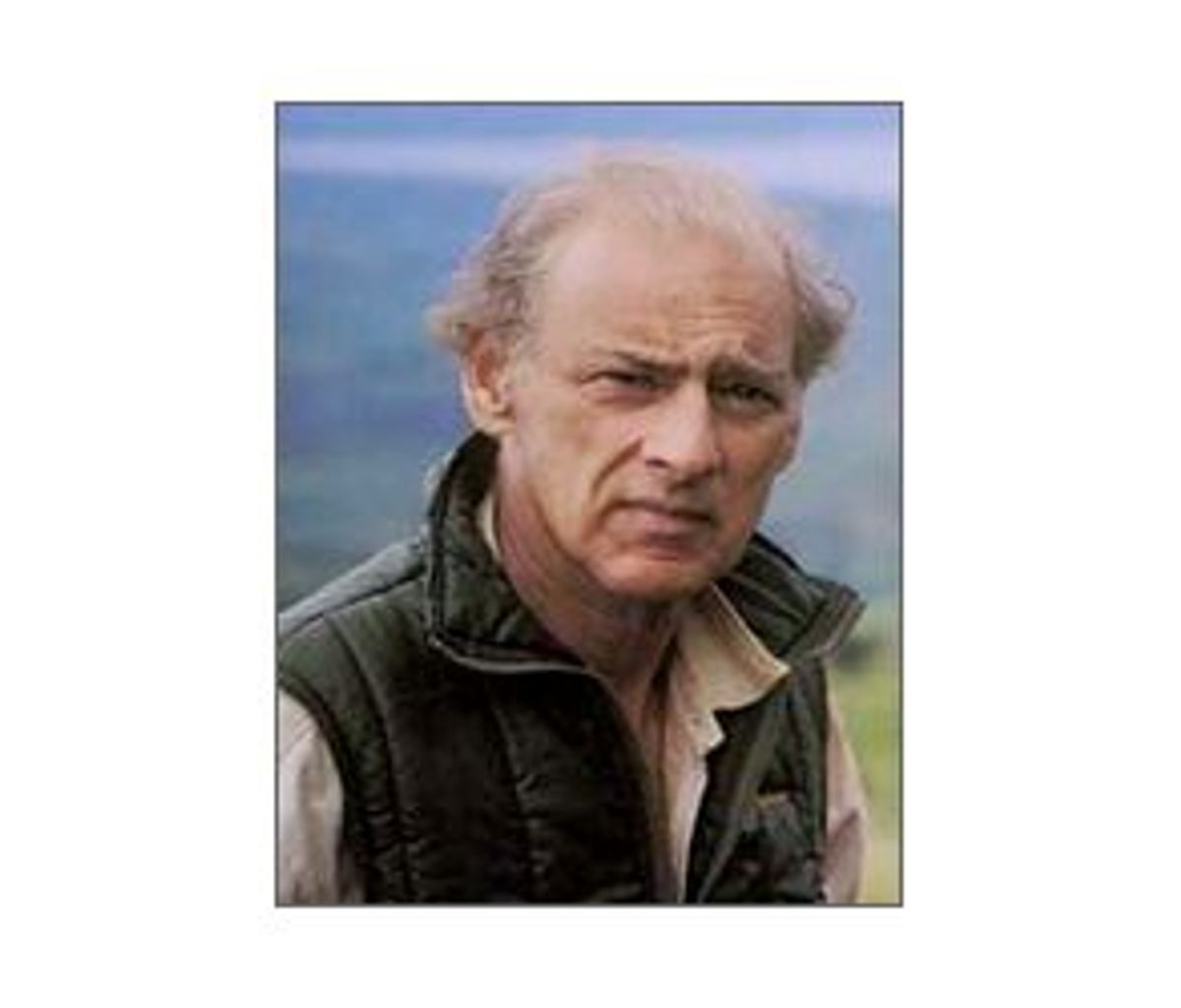

Christopher Ondaatje was raised in one of Sri Lanka's most powerful

colonial families. And though his family later fell into poverty, he went on

to create a billion-dollar empire in Canada. Along the way Ondaatje, 66,

became an Olympic sportsman, then turned his hand to writing and achieved

bestseller status as a biographer. He has also carved a reputation as an

accomplished explorer, wildlife photographer, philanthropist and

international art collector.

"In the early 1970s, I was steeped in the world of North American finance,"

he says in a precise, clipped voice. "Then I read a book, called 'The Devil

Drives,' by Fawn Brody, and it changed my life."

Tall and elegant, the older brother of poet-novelist Michael Ondaatje

looks at the pictures on the walls around us as he talks. "'The Devil

Drives' is a biography of Victorian explorer Sir Richard Burton," he says,

with a faint colonial twang to his words. "I was hacking my way through the

jungles of finance, and I suddenly realized his was the life I would have

preferred to have led. For over a quarter of a century, I have been

fascinated with Burton. And I was obsessed by his search for the source of

the Nile with John Hanning Speke over 150 years ago, which contributed to

his being the best-known traveler of the 19th century.

"I was obsessed, obsessed, by the source of the Nile for over 20

years. It was on my brain 99.9 percent of the time."

Ondaatje's fascination with Burton, Speke and the Nile River has indeed

changed his life. It led him to give up his business and embark on a series

of perilous journeys into the heart of equatorial Africa to find the true

source of that mighty river.

Ondaatje might at first seem an unlikely explorer. In his adopted country of

Canada he is a national name, recognized as an extraordinarily successful

financier who has given millions to galleries and public institutions. On

the international stage, his Sri Lankan art collection is the largest of its

kind in the world, and the six books he has written, including the

semiautobiographical "The Man-Eater of Punani," about his rediscovery of his

native Sri Lanka, and the recently published "Journey to the Source of the Nile,"

about following in the footsteps of the famous Victorian explorers in

eastern and central Africa, have been bestsellers.

However, in the U.K., where he now lives, he remains something of a mystery.

He is the philanthropist behind the annual 10,000-pound (about $14,740)

Ondaatje Prize for Portraiture, offered each summer by the Royal Society of

Portrait Painters. And he is recognized as a prominent council member of the

Royal Geographical Society. Yet despite the apparent generosity of his

Ondaatje Foundation to various British causes, his is scarcely a name on

everyone's lips.

That could soon change. On May 4, Ondaatje was revealed as the man behind

the new $23.4 million expansion of the National Portrait Gallery in London.

According to director Charles Saumarez Smith, Ondaatje's "incredibly

generous" gift of almost $4 million allowed lottery funding to be secured

and the project to go ahead. "The NPG has for some time been my favorite

gallery in England, if not the world," says Ondaatje. "It's one of the very

few galleries in the world that is devoted to portrait painting."

His role as a philanthropist and explorer seems a world away from his

beginnings in what was then Ceylon, muses Ondaatje, as we sit and sip strong

black coffee in the opulent surroundings of his Sloane Square apartment. "I

must have been a strange boy," he recalls. "Tall, slim and angular. Always

alone. Always thinking."

His father, Mervyn, was a plantation owner, part of a prominent line

descended from Dutch burghers, who arrived on the island in the 17th

century. One ancestor produced the first translation of the Bible into

Tamil, and the young Ondaatje's uncle on his mother's side was Ceylon's

attorney general.

Mervyn emerges as a sort of lovable maverick in "Running in the Family," Michael

Ondaatje's fictionalized account of the children's upbringing. A major in

the Ceylon Light Infantry, Mervyn was "a big man with sandy hair and blue

eyes, bigger than his own father, and he was incredibly charismatic; he

could sell anybody anything," remembers the older Ondaatje brother.

Mervyn spoke Sinhalese and Tamil fluently and managed various estates.

"Unfortunately, he never got out of the habit of drink. For most of the time

I knew him, he was sober, but occasionally he went on a binge." The binges

would start as soon as he got up in the morning. "No one could predict what

he would do," Ondaatje says. At these times, his father was feared by both

the family and the estate workers.

It was at school that he fell in love with cricket, and he vividly recalls the West Indies playing at Taunton in 1951. However, the idyllic days were soon shattered. Just before his last year at Blundell's he received a letter from his mother, telling him he would have to leave because the family had lost all their money, as a result of problems after Ceylon gained independence from Britain.

"I had had no idea of the family's financial troubles," wrote Ondaatje later. "Like most privileged children, I didn't think about things like that. I had to leave before experiencing the best years of school life. In some ways, the shock of being forced out of my second home was more brutal than that of being away from Ceylon. I left, and on my 17th birthday ended up working in London."

There was one positive point; his mother came to stay in England and the two were reunited. Then, in 1956, instead of taking up a job offer as the assistant manager of a bank back in Colombo, Sri Lanka's capital, he "realized the colonial game was up." "I made a key decision in my life to go west. So I started a financial and banking career in Canada," he says.

His aim, he says, was "to rebuild the family's fortunes." With just $13 in his pocket when he arrived, and surviving for a time on a diet of toast and coffee, he worked his way up through the world of banking before establishing a hugely successful network of companies in the publishing and corporate finance sectors.

In 1970, he helped found Canada's first institutional brokerage, Loewen, Ondaatje, McCutcheon & Co. And Pagurian Press, which he created in 1967 with a $3,000 budget, eventually grew into the Pagurian Corp., worth $500 million and controlling assets of $1.2 billion. It was his understanding of "paper," he says enigmatically, that helped him achieve his success.

At the same time, Ondaatje indulged his keen interest in sport, representing Canada in the bobsledding competition at the World Championships in 1960 and at the Olympic Games in '64, when the country won a gold medal. He also wrote and financed the publication of the first of his bestselling books, "The Prime Ministers of Canada: 1867-1967," in 1967. It eventually sold 600,000 copies.

It was during this period that Ondaatje married his Latvian wife, Valda -- someone who "understood the devils" in him, as he writes in the dedication of "Journey to the Source of the Nile" -- and brought his younger brother, Michael, to the country.

"When he was 18, I pulled him out to Canada to go to university. He immediately latched onto the literary set," Ondaatje says, "where he set about developing his budding flair for drama and writing." It was a chance for the brothers to reacquaint themselves: "He's 10 years younger than me and we didn't really have a chance to get to know one another in earlier life. I was in England and he stayed behind with the family in Ceylon."

Are they close now? "Oh, sure!" Ondaatje exclaims. He talks of watching Michael's writing develop and mature, calling his brother a "literary purist in the truest sense of the word."

"So what kind of person is he?" I ask.

"He's a nice guy," replies Ondaatje, clearing his throat in the warm, constant air of the apartment. "But I think he's more laid-back, more literary than me. The literary world is his all-consuming passion. He's a poet, really. He's earned his success; he worked hard for it. I don't think my brother wanted to do anything else [but write]. And despite my success in finance, I felt that way too. I always have."

As his business life prospered, this feeling intensified. Something was missing -- the kind of life and adventure he had read about in books about the famous Victorian explorers, particularly Burton (of whom he owns several original Victorian-era paintings). "I wanted to write an adventure story. More than that, I wanted to actually have the experience myself," he says.

He pauses for a moment. "Being kicked out of my house and my family in 1947 forced me to become worldly-wise and to be able to think for myself and make decisions very early on. But 'making it' [in the business world] is a selfish business."

So he sold his business interests in 1988, "fed up with the world of financeand greed, and the uncertainty of the economic clouds. I was worried too that I wouldn't have enough time to do all I wanted with my life. I didn't want to die with 'financier' written on my gravestone." Ondaatje promptly resigned all his directorships and moved back to England to "be close to the Royal Geographical Society and to spend my life on adventure and writing."

In 1947 Mervyn sent Christopher to be schooled in England at Blundell's, a public school in Devon. "I didn't see my father ever again," says Ondaatje, turning away, "and next saw my mother when I was 17." During this time, his mother also divorced her husband -- an "awful time" that Ondaatje says he will never forget.

His first step of liberation was a journey to East Africa in 1988, which led to his book "Leopard in the Afternoon." Then there was the pull of Sri Lanka, which he hadn't visited for nearly 40 years. "It is true that I was sent to England to school and I then decided to go to Canada to rebuild my family's lost fortunes," he says. "But I never got Sri Lanka out of my system. I always wanted to return, but the shame of what had happened to our family prevented me. Eventually I chucked everything and did all the things I should have done years ago, including returning to Sri Lanka to come to terms with the ghost of my father."

This shame became one of the driving forces in his life -- and the self-avowed "selfishness" of his business career -- and it was only in writing "The Man-Eater of Punani" (1992), about the voyage back to the island of his youth and the search for his lost heritage, that he began to come to terms with his past. "Every writer has one book which is their best book. 'Man-Eater' is mine," says Ondaatje. "It really is an autobiography and a love letter to my father -- whom I never saw again. With it, I rediscovered my roots."

This interest in Sri Lanka also manifested itself in Ondaatje's growing art collection. What began as a humble passion has grown into the largest private collection of its kind in the world, stored at his mansion, Glenthorne, in north Devon. It contains maps, manuscripts, etchings, watercolors, paintings, armor, swords, daggers, knives and various objets d'art. The finest of all his Sri Lankan antiquities is a replica of Tara, a solid bronze-gilded image of the sakti -- or female essence -- of the bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokitesvara. (The statue has been held in the British Museum for the past 170 years.)

As if that were not enough, Ondaatje also forged a career as one of the world's leading experts on the Victorian explorers of the Nile, writing a book about Sir Richard Burton's early life, "Sindh Revisited," and retracing the footsteps of Burton and his contemporaries -- John Hanning Speke; society darling Samuel Baker and his wife, Florence; Dr. David Livingstone; and Henry Morton Stanley -- to see if Speke had indeed, as was claimed, found the true source of the Nile at Lake Victoria.

Since Herodotus in the fifth century B.C. and Ptolemy in the second century, men had been trying to find the Nile's true source. However, it was Speke who, in 1858, said, from the summit of a hill overlooking what is now Lake Victoria, near the present-day town of Mwanza, Tanzania, "I no longer feel any doubt that the lake at my feet gave birth to that interesting river, the source of which has been the subject of so much speculation and the object of so many explorers."

This declaration was to win him fame and adulation, and in turn launch the fabled "race for Africa" among the colonial powers. "History changed forever," Ondaatje says simply. However, Speke had concealed the true nature of his discovery from Burton, the expedition leader, and hurried to England to present his findings to the Royal Geographical Society -- despite the fact that the men had agreed to wait for each other before announcing any discoveries.

After a second expedition undertaken with James Augustus Grant, Speke mysteriously died in a shooting accident in 1864, the day before he was to debate the Nile discoveries with a by-now hostile Burton. "I've no doubt Burton would have ripped him to shreds," says Ondaatje -- particularly because on his second journey, Speke had ruminated in his notes that the Kagera River fed Lake Victoria (thus making it a tributary of the Nile), yet failed to present these findings, perhaps fearing it might lessen his glory.

In 1996, Ondaatje's passion for this question and these men's lives led him on a three-and-a-half-month expedition to the Great Rift Valley lakes of eastern and central Africa. The only way he could prove his own theories about the Nile's origins was, as Ondaatje puts it, "to go there."

So, with his team of local guides, he followed Burton and Speke's trail, "even into blind alleys, across rivers, through marshes, through fens, bogs, forests, getting lost, places right off the map, [even though] practically all the place names on Burton's map are not the same anymore.

"We had a helluva job to go through this thing," Ondaatje says, "but it was

an extraordinary exploration achievement for Burton and Speke. So we went

where they went, slept in the same places they slept, kept to the same dry

lakes they kept to and so on."

With him, Ondaatje took all the various Victorian explorers' journals, so

that "we experienced much that they had, whilst reading about their

experiences."

Baker had claimed during his journey (after Burton and Speke's) that Lake

Albert and Lake Victoria were the sources of the Nile. "And why not?" says

Ondaatje. "He was damned near the truth. These are the two mighty reservoirs

of the Nile. But they are in turn fed by two rivers, the Kagera and the

Semliki. And they drain the Burundi Highlands in the first case, and the

Ruwenzori Mountains, the famed 'Mountains of the Moon,' in the second case."

Ondaatje had found the Nile's true source.

The journey was not without danger, however. Attempting to climb the

Mountains of the Moon, his team was stopped by the arrival of 5,000 rebels

in the local town. (This was the start of the war by Gen. Laurent Kabila

against President Mobutu Sese Seko's regime in what was then Zaire.) "I

didn't know what was happening; it was a terrifying moment, and we were

unbelievably lucky to get out."

Wading through swamps, marshes and bogs, Ondaatje now recalls, "I had been

where no other Victorian explorer had been. Not Burton, not Speke, not

Baker, not Livingstone, not Stanley. I knew I had crossed the line. I had in

fact earned my own prize. And I am probably the only person ever to have

done all their journeys."

Recalling the similar passions of his heroes, Ondaatje's drive and obsession

are clear in his voice, the past very much alive in his work. He says that

he is now living the life he always wanted to lead. "I've got adventure,

travel; I've got writing, cricket; and I've got art." He speaks fondly, too,

of his wife and their three grown children, now living across the world.

"He's a great friend, an incredibly energetic man," says Charles Saumarez

Smith. J. Robert Knox, keeper of the Department of Oriental Antiquities at

the British Museum, calls Ondaatje "a complex character. He brims over with

talents, facts, ideas and charm. He has an astonishing store of energy,

leaving most ordinary people gasping in the wake of his lightning

explanations of his theories and his collections. He is an entrepreneur and

man of the world with single-minded determination."

For Ondaatje himself, there is just one more ambition: "I want to do one

more book, call it the 'Last Safari,' trying to piece all the things I've

done, from my early life to the last 12 years, to try and fit together this

urge to achieve the unobtainable and what you have to do to get there,

because preparation is everything. You have to cross the line to achieve it.

"The black leopard for me is the symbol, the talisman, the thing that I

could never get," he says. "But now, late in my life, I've seen it and would

like to write about it as a symbol of things that I would like to try and do

-- the countries that have made me, spawned me, also the countries that have

tended to destroy themselves."

Shares