It's Kenya's national sport, the passion of the masses. Little boys dream that one day, they might soak up the cheers of the adoring fans that regularly crowd the stands at the National Stadium in Nairobi. The best players are national icons. The selection process to spot the great stars begins at a very young age. Coaches backed by federal outlays comb the countryside to find the next generation of potential athletes. The most promising of the lot are sent to special schools and provided extra coaching. It's not an exaggeration to call Kenya's national sport a kind of national religion.

According to conventional and socially acceptable wisdom, this is a familiar story -- the sure cultural explanation for the phenomenal success of Kenyan distance runners. There's only one problem: The national sport, the hero worship, the adoring fans, the social channeling -- that all speaks to Kenya's enduring love affair with not running, but soccer. Despite the enormous success of Kenyan runners in the past 15 years, running remains a relative afterthought in this soccer-crazed nation.

Unfortunately, Kenyans are among the world's worst soccer players. They are just terrible. Despite an elaborate school system and the expenditure of hundreds of thousands of dollars of the country's sparse sports resources, Kenya, the most populous and affluent country in East Africa, is regularly trounced by far smaller countries in West Africa. In fact, there is no such thing as an East African soccer powerhouse. The same thing is true of sprinting. Kenya has tried desperately over the past decade to replicate its wondrous success in distance running at the sprints, to no avail. The best Kenyan time ever in the 100 meters -- 10.28 seconds -- ranks somewhere near 5,000th on the all-time list.

What's going on here? And for that matter, why is it that every running record, from the 100 meters to the marathon, is held by an athlete of African ancestry? Is it racist and a white obsession to be curious about such phenomena?

In America, the convenient explanation for the tepid performance of whites in running, basketball and, increasingly, football is that blacks just work harder at them, because of cultural expectations and in part to escape sometimes desperate poverty. That's dubious and I believe racist. Do cultural factors matter? Of course: There are no Texans, white, black or Latin, starring in the National Hockey League. But there is little more than speculation in support of assertions that the racial disparities we see in sports success are "determined," as many sociologists claim, by social factors alone.

Frankly, such claims that blacks succeed for cultural reasons diminishes the reality that sports achievement is all about individual accomplishment -- fire in the belly. It's hard work, courage and serendipity that separate champions from the rest of the elite sports men and women.

Consider Michael Jordan, who grew up in the security of a two-parent home in comfortable circumstances. Or Grant Hill, son of a Yale-educated father and a Wellesley-graduate mother. Or one of the world's top sprinters, Donovan Bailey, who was certainly not motivated by a desperate need to escape destitution: He already owned his own house and a Porsche, and traded life as a successful stockbroker to pursue his dream of Olympic gold. More and more top black athletes are from the middle class.

And just look at the athletes winning medals in the Sydney Olympics. Why is the success of blacks and other minorities such as Aboriginal Australians explained away by cultural channeling? Sports success is too complex a phenomenon to be tidily settled by such facile sociology. How do we explain the success of the majority of athletes, of all nations and ancestral heritage, who lived in comfortable circumstances? The classic argument that blacks succeed in sports to escape poverty is less and less plausible and more and more racist every day.

Genes may not determine who are the world's best runners, but they do circumscribe possibility. Kenyans and other East Africans have an innate capacity, not an innate ability, to thrive in distance running; individual effort and courage separate the pretenders from the stars. Success in sports is a biosocial phenomenon.

In Kenya, the cultural argument for the country's lackluster sprinting and soccer success amounts to an assertion that aspiring sprinters and soccer players don't train hard enough to keep up with their African brethren on the west side of the continent. That's sheer nonsense. Kenyan training regimens, in all sports, are legendary.

No amount of political correctness can obscure the reality that a large part of Kenyans' mediocre record in soccer and sprinting comes down to genetics: They just don't have the body or physiology for those sports. They are ectomorphs, short and slender, with huge natural lung capacity and a preponderance of slow twitch muscles, the energy system for endurance sports. It's a perfect biomechanical package for distance running, but a disaster for sports that require anaerobic bursts of speed -- like sprinting and soccer.

Kenya, with but 28 million people, is the world epicenter in distance running, which only became widely popular in the late 1980s. Today, Kenyans hold more than one-third of the top times in middle- and long-distance races. Including top performances by other East Africans (most from Ethiopia), that domination swells to almost 50 percent. The Kalenjins of the Great Rift Valley adjacent to Lake Victoria, a loosely named population of 1.5 million people, win almost 40 percent of major international distance events. One tiny district, the Nandi, with only 500,000 people -- one-twelve-thousandth of Earth's population -- sweeps an unfathomable 20 percent, marking it as the greatest concentration of raw athletic talent in the history of sports.

At the Seoul Olympics in 1988, Kenya shocked the running world when its top male runners won the 800 meters, the 1,500 meters and the 5,000 meters, plus the 3,000-meter steeplechase. Based on population percentages alone, the likelihood of such a performance is one in 1.6 billion. The more recent figures are even more staggering. At the World Cross Country Championships in 1998, arguably the most competitive running event in the world, each country was limited to six entries. The Kenyans finished No. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7; the No. 3 finisher was from Kenya's East African neighbor, Ethiopia.

Why does the claim that sports success is biosocially based get some people so nervous? After all, it's conventional science that different body types have evolved in response to differing environmental conditions in different regions of the world.

The elephant in the living room, of course, is "race." Fascination about black physicality and black anger about being caricatured as lesser human beings have been part of the unspoken side of the American dialogue on race for hundreds of years. The fear is that some might conclude that if blacks are faster on average, they must, as part of zero-sum reasoning, be weaker mentally. But that's a conclusion not supported by science.

Race is a term soaked in much folkloric nonsense. The concept of race is somewhat akin to a sloppy Joe masquerading as a hamburger. It's a pretty messy concept, sometimes referred to as "fuzzy sets" or extended families. Although racial labels are helpful terms, and I use them in my book, "Taboo: Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports and Why We Are Afraid to Talk About It," they can leave misconceptions. Many traits are correlated, such as dark skin color and the presence of the sickle cell gene. But such links are not absolute. Blacks who have evolved in cooler climates are no more likely to contract sickle cell than are nonblacks. Although many blacks are lactose intolerant, a result of the utter lack of milk-producing animals in much of sub-Saharan Africa, the Masai, with their tradition of cow and goat herding, are perfectly able to digest milk products.

"Race," as we popularly talk about it, carries enough racist baggage as to be problematic at best. It leads to simplistic generalizations that link vague concepts such as "intelligence," "violence" and "sexual aggressiveness" to populations grouped by skin color. That's why top geneticists, such as Stanford's Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, while basing their research on a recognition of populationwide genetic differences, eschew the term "race."

As Cavalli-Sforza has so brilliantly demonstrated, trait variations are the result of waves and crosscurrents of migrations that at times -- frequently even -- belie the folkloric racial categories. This is true, of course, even in sports. Pygmies, who certainly have black skin, are not particularly good athletes. It's no surprise that their genetic history distinguishes them quite dramatically from much of the rest of sub-Saharan Africans. Similarly, the Lemba tribe of southern Africa was recently shown to be genetically linked through the Y chromosome to the Jewish population of Mesopotamia some 2,000 years ago. In key genetic ways, they are quite distant from many other Africans.

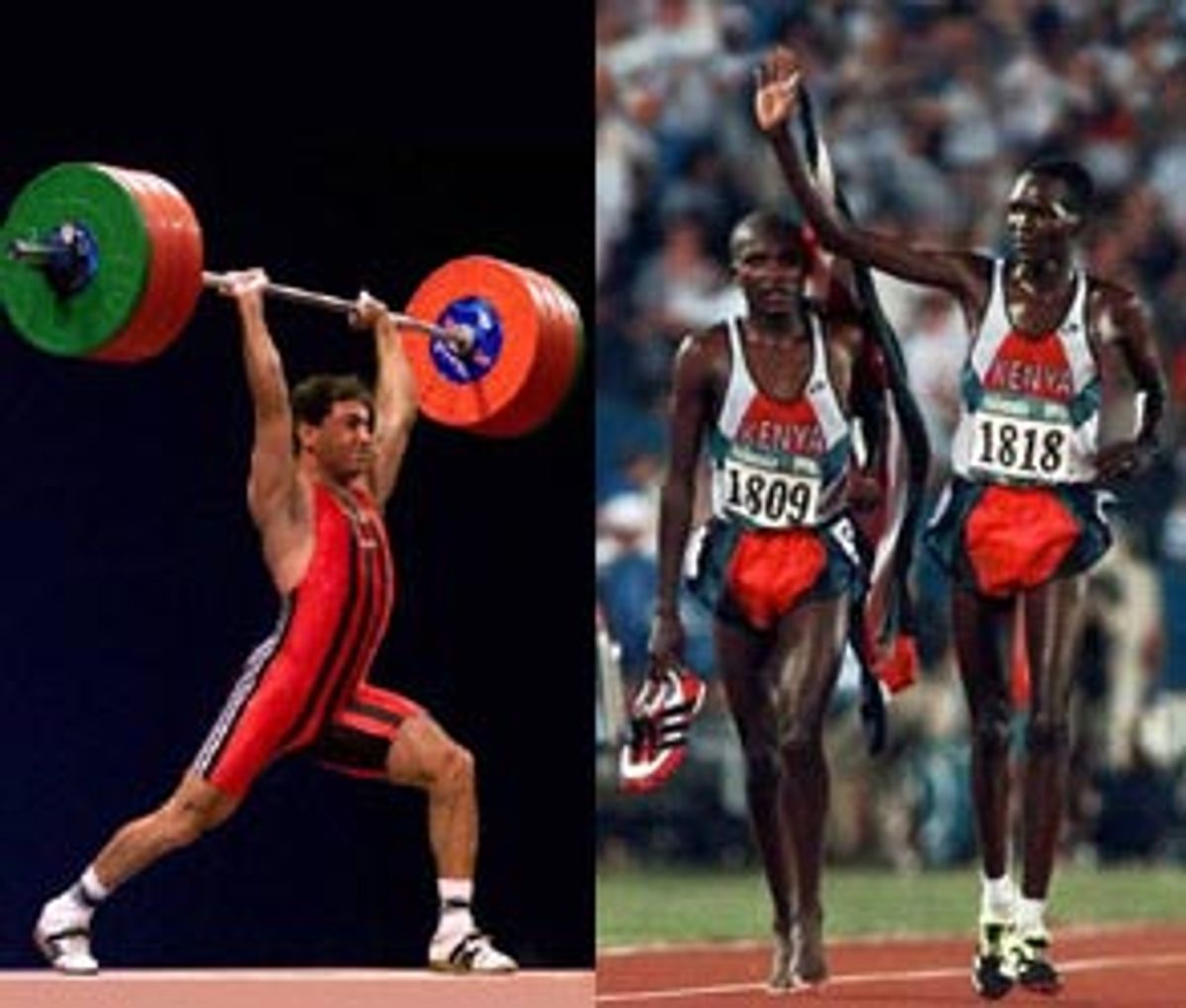

With these many exceptions in mind, it remains largely true that some body type and physiological patterns show up in various mega-populations such as West Africans, Eurasian whites, East Africans and East Asians. Today, no credible scientist disputes that evolution, along with local social conditions, has helped shape Kenyan distance runners, white power lifters, with their enormous upper-body strength, and athletes of West African ancestry who are explosive runners and jumpers.

What have scientists documented? Whites of Eurasian ancestry, who have, on average, more natural upper-body strength, predictably dominate weightlifting, field events such as the shot put and hammer (whites hold 46 of the top 50 throws) and the offensive line in football. Where flexibility is key, East Asians shine, such as in diving and some skating and gymnastic events -- hence the term "Chinese splits." Just watch the Olympics and you will see: There are no prominent Chinese sprinters, no runners of any note until you get to the longest distances and no jumpers, but the Chinese flourish in diving and gymnastics. Is this totally a product of cultural factors? It's extremely doubtful.

Despite this remarkable confluence of massive on-the-field empirical evidence and overwhelming heritable anthropometric and physiological characteristics, some sociologists and a coterie of ideological evolutionary biologists seem determined to distort this fascinating phenomenon by turning it into a racial issue. Some argue that the empirical and scientific data should be ignored in favor of a personal conviction that humans are a tabula rasa, a blank slate for society and environment to write upon.

In light of recent advances in genetics and the science of human performance, such extremist beliefs appear quaint, dangerous and even racist. Indeed, populationwide differences are widely acknowledged in disease research. Many populations of sub-Saharan African ancestry are genetically predisposed to contracting colorectal cancer, Eurasian whites are genetically prone to multiple sclerosis -- and East Asians by and large are victims of neither.

Why do we so readily accept that evolution has turned out blacks with a genetic proclivity to contract sickle cell, Jews of European heritage who are 100 times more likely than other groups to fall victim to the degenerative mental disease Tay-Sachs and whites who are most vulnerable to cystic fibrosis, yet find it racist to acknowledge that blacks of West African ancestry have evolved into the world's best sprinters and jumpers and East Asians into the best divers?

Yet that's the typical position staked out by ideologues such as University of North Carolina at Charlotte anthropologist Jonathan Marks. Marks rails against even discussing the issue of human differences on the basis of his disingenuous assertion that the dramatic patterns of athletic success by athletes of different ancestral origins cannot be proved, in a laboratory, to be linked to specific genes. "If no scientific experiments are possible, then what are we to conclude?" he writes. "That discussing innate abilities is the scientific equivalent of discussing properties of angels," is "outside the domain of modern scientific inquiry" and therefore should not be pursued.

What a breathtakingly simplistic -- and indeed racist -- claim, that we should not even discuss the science of sports. Such a stand enrages many geneticists engaged in lifesaving research. "I believe that we need to look at the causes of differences in athletic performance between races as legitimately as we do when we study differences in diseases between the various races," declares Claude Bouchard, a leading geneticist studying obesity and athletic performance and director of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, La. "In human biology ... it is important to understand if age, gender, race, and other population characteristics contribute to the phenotype variation," he writes in the American Journal of Human Biology. "Only by confronting these enormous issues head-on, and not by circumventing them in the guise of political correctness, do we stand a chance to evaluate the discriminating agendas and devise appropriate interventions."

Of course we have heard echoes of this debate before. It's similar to the classic defenses of the indefensible, such as the tobacco industry response to charges that smoking causes cancer and the creationist attack on evolution. For years, tobacco lobbyists have held that because there is no confirmed laboratory "proof" that smoking directly causes cancer in humans (independent of uncontrollable individual circumstances), we should not consider this an issue of "science."

Similarly, creationists have argued (in an unsuccessful legal brief before the Supreme Court by the Creation Legal Research Fund) that there is no direct "proof" for human macroevolution. "The evidence for evolution is far less compelling than we have been led to believe," states the brief. "Evolution is not a scientific 'fact,' since it cannot actually be observed in a laboratory."

Such posturing by the tobacco industry, creationists and environmental determinists is scientific hogwash. As Barbara Ehrenreich and Janet McIntosh wrote in the liberal weekly the Nation in 1997, this is yet another round of an unrelenting, almost hysterical, attack on the scientific method by a coterie of influential social thinkers, including Marks of UNC-Charlotte. Its goal is entirely political: to caricature the clear scientific fact that there are biologically based commonalties in populations to support the now-discredited belief that humans are a blank slate, shaped entirely by their environment and culture.

This ideologically driven perspective is infected by a fundamental misunderstanding of scientific reasoning, which rarely lends itself to "smoking guns" and absolute certainty. The search for scientific truth is a process. It may be years before we identify a gene that ensures that humans grow five fingers, but we can be assured there is one, or a set of them. We have yet to find the gene set for height, yet we can be quite certain that if one exists, men will be more likely to have it than women. Most theories, including those in genetics, rely on circumstantial evidence tested against common sense, known science and the course of history. If scientific theories depended only upon observable evidence or laboratory experiments, then everything from the theory of relativity to the certainty that the Earth revolves around the sun could be written off as speculative.

The fact that geneticists cannot yet isolate the chromosomes that contribute to hip-shifting, breakaway running does not automatically undermine the theory that such skills are genetically based -- any more than the lack of an eyewitness at a crime is proof that the crime never happened. It may be years before geneticists isolate particular strands of DNA linking population clusters to athletics, "but that is not the same as saying that there is not a genetic basis for the racial patterns we see in sports," asserts Bengt Saltin, a physiologist, director of the Copenhagen Muscle Research Institute and author of the cover story on why athletes are born, not made, in the September Scientific American. "Identifying genes will not and cannot expect to resolve the issue. The basis for the success of black runners is in the genes. There is no question about that."

Although ideological critics will undoubtedly continue to spin this issue, "what began as a healthy skepticism about misuses of biology [has become] a new form of dogma," write Ehrenreich and McIntosh. "Like the religious fundamentalists, the new academic creationists defend their stance as if all of human dignity -- and all hope for the future -- were at stake," they add. But "in portraying human beings as pure products of cultural context, the secular creationist standpoint not only commits biological errors but defies common sense."

Here's a challenge to academic creationists, who are far better at mau-mauing than rational debate: If there are no biological differences that contribute to the vast performance disparities in sports, what is the explanation for the fact that 498 of the top 500 100-meter times in history are held by athletes of primarily West African ancestry? And why shouldn't we discuss it?

Limiting the rhetorical use of that problematic concept of race, an admirable goal, is not going to make the patterned biological variation on which it is based disappear. Although people share a common humanity, we are different in critical ways, such as our varying genetic susceptibility to diseases.

Sports is a wonderful metaphor to encourage a constructive discussion of the wonderful benefits and potential ethical concerns ushered in by the revolution in genetics. Indeed, if we do not welcome the impending genetic revolution with open minds, if we are scared to ask and to answer difficult questions, if we lose faith in science, then there is no winner; we all lose. The question is no longer whether genetic research will continue but to what end.

Athletic competition, which offers a definitiveness that eludes most other aspects of life, is a perfect laboratory for a serious exploration of our humanity. The challenge is in whether we can conduct the debate so that human diversity might be cause for celebration of our individuality rather than a source of distrust. After all, in the end, for all our differences, we are far, far more similar.

"If decent people don't discuss human biodiversity," writes George Mason University professor Walter Williams in a review of "Taboo" in American Enterprise magazine, "we concede the turf to black and white racists."

Shares