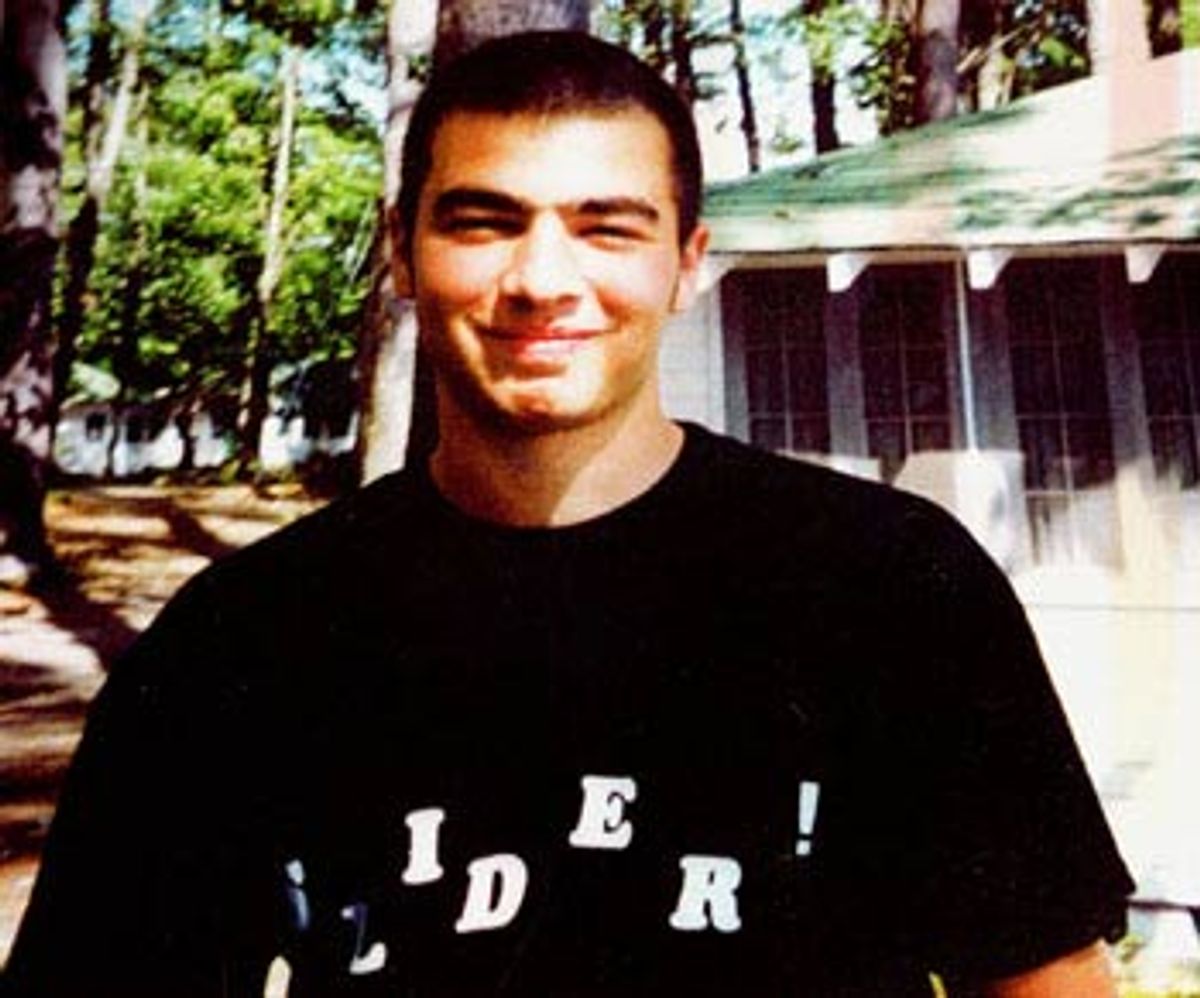

With his die-hard optimism and winning smile, 17-year-old Asel Asleh didn't look like a tormented teenager. Both an Arab and an Israeli, Asel moved between the two conflicting worlds with the ease of a talented, outgoing kid who was everybody's best friend.

But when Arabs started throwing stones at Israelis and Israelis fired back with bullets, Asel, a passionate peace activist, was jerked to one side. He was beaten and shot dead by Israeli police during a riot near his village, Arabeh, on Monday.

Ironically, Asel was wearing the green T-shirt of Seeds of Peace -- a U.S.-sponsored youth organization that brings together Arabs and Jews -- at the time of his brutal death.

To his Arab friends, Asel's death makes the world ugly but simple: Asel (pronounced As-SEAL) was a hero, a martyr and a victim of Israeli racism and unchecked force. The day after his death, 30,000 people followed Asel's body to the cemetery where it was buried, wrapped in a Palestinian flag.

To his Jewish friends however, Asel's death raises dizzying questions they can't seem to put to rest: Could Asel, the peacemaker, have turned his back on his ideals?

And why did the Israeli police shoot to kill?

Both Arab and Jewish reactions to the news of Asel's death reflect the trauma that is ripping Israel apart again. Seven years after the end of the intifada -- the Palestinian uprising that shocked Israelis and Palestinians into trying to make peace -- a new generation is learning the price of boundless hatred and grief.

On Friday, the eighth day of deadly clashes in the Holy Land, there was no sign of the violence abating. On the contrary, riots after Muslim Friday prayers in Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza brought the death toll to at least 77, nearly all of them Palestinians.

Although Asel was Israeli, his death was mentioned only in passing in Hebrew newspapers, as one of scores of Palestinians and Arab Israelis killed in clashes in the last week. In short, a faceless statistic.

The circumstances of Asel's death were, indeed, unexceptional. The police say Asel was among hundreds of youngsters who blocked a road and attacked policemen "with stones, bottles and even gunshots" in one of many demonstrations that turned violent in the Galilee on Monday. Kobi David, spokesman for the Galilee police, said that Asel "was seen throwing stones at the police," but did not provide further details. He also said the police were forced to shoot rubber bullets to protect themselves.

Asel's family and several eyewitnesses give a different account of the scene. According to them, the demonstration was a mostly peaceful one, a show of solidarity between Israeli Arabs (who live in Israel proper) and Palestinians (who live in the West Bank and Gaza) against the brutality displayed by Israeli forces after a riot erupted at Jerusalem's al-Aksa mosque last Friday. They claim police charged Asel when he tried to rescue a friend who was fatally shot in the chest after stepping forward to throw a stone at a line of Israeli police. They say Asel fell, was beaten severely (his head and back were black with blood and bruises) and shot in the neck at close range with a rubber bullet.

"Beating him was not enough," said Nardin, Asel's older sister. "They had to shoot him. The police were not only doing their job, they had hatred inside. That was the deadly combination that killed him."

After Asel was on the ground, motionless, friends and witnesses say, the police allegedly taunted other Arabs to "come and get him" -- and meet the same fate. Asel died more than an hour and a half later, after his ambulance was held up at a checkpoint, in a nearby hospital. Asel's uncle, a doctor at a public hospital, examined the body before the burial but no autopsy was conducted.

Whether Asel was throwing stones at the police or not, neither version of the story makes much sense to Asel's Jewish friends.

At the Jerusalem headquarters of Seeds of Peace, where poems, candles and pictures from summer camp and parties form a makeshift shrine to Asel, a handful of 17-year-old Jewish Seeds graduates wrestled with their incredulity.

"If Asel was throwing stones, were his three years in Seeds for nothing?" asked Keren Klein.

"People use violence when they have given up hope of expressing themselves -- that was not Asel," said Dana Noar, recalling Asel's gift for languages (he spoke Arabic, Hebrew and English fluently) and his unstoppable urge to send long, articulate e-mails to all the friends he made at Seeds.

A "computer freak" who devoured books of philosophy and politics and was looking forward to college, Asel was a model of ambition, not despair. He wanted to do something with his future, his friends are certain. He could have become a politician or an engineer -- "a leader in what he did," said Dana.

"I want to believe," reads a poster in his bedroom, and indeed, his optimism was contagious. Moran Eizenbaum remembers how Asel helped her through rough times, when, after coming back from an idyllic Seeds of Peace summer camp, schoolmates called her an "Arab-lover" and Israel's black-and-white reality gave her a slap in the face. In his trademark friendly way, Asel sent her comforting e-mails, called her and even invited her to his home for a festive meal.

As Keren, Dana and Moran sat reminiscing about Asel, the ultra-friendly guy who would never have hurt a fly, a scary thought crept into their minds. What if the Israeli police had shot Asel for no reason?

Moran at first rejected the thought. "I love my country and I believe the soldiers are just trying to protect me. I don't think they shot him for no reason," she said. "On the other hand they killed Asel and I loved him. I can't believe he was a threat to the security of Israel."

While Moran and her friends sank into a state of confusion, the world for Bashar Iraqi, a 16-year-old Israeli Arab and friend of Asel's who joined Seeds of Peace last summer, seemed never to have been so clear.

"Before, we knew [the Israeli Jews] had something against us, but we didn't know what. We finally saw it in these demonstrations," he said. "We're supposed to be Israeli citizens but they don't treat us that way. We would have been treated better if we were animals."

Like Asel, Bashar has had to navigate the shoals of a dual, conflicting identity. "We treat them as friends, buy from them, pay taxes and try to be loyal [to Israel] although their national anthem and flag don't represent us," he said. As part of Israel's 18 percent Arab minority, Bashar goes to a school where classes are taught in Hebrew and he carries an Israeli ID card. But by blood, tradition and mother tongue, he is a Palestinian Arab.

In Seeds of Peace, Asel found the maturity and the desire to overcome this tension. In a letter published in the Olive Branch, the organization's newspaper, he wrote to a fellow Israeli Arab: "I can never take the word Israel off my passport, or the word Arab, which I feel proud of ... We don't have to be caught [between the two]; we can lead these two worlds and still keep everything we had."

For Bashar, those hopes are now shot. "I still believe in peace," he reassured Moran as the two rode in the back of a minivan headed for the Galilee to make a visit of condolence to Asel's family.

But a moment later Bashar's anger burst from his chest. "We live a lie called peace; we live in a lie called a democratic country. They say we're citizens of Israel so how could they do this to us?" Like many others, Bashar was particularly upset by the level of force used to disperse demonstrators. The police could have used batons or water hoses instead of bullets, he said. "They don't do this to other Israelis. They've started a war against their people."

Ten Israeli Arabs have been killed so far by Israeli forces during this week's riots. As the hot, still evening dragged on and Moran was exposed to the periodic shrieks of grief of Asel's mother, seated with relatives and well-wishers, under a large canopy hung from the tallest branches of olive trees, the senseless brutality of Asel's death began to sink in.

"It's so hard growing up in Israel," she said, emotionally exhausted after listening to repeated descriptions of Asel's bruises, bullet wounds and the probable cause of his death.

"I was brought up to believe the army does good," said Moran. "My roots are here. My father served 30 years in the army. I already have my draft date," she said. Her compulsory military service will start next fall. "I can't imagine myself part of that now."

Shares