About midway through his book about Postville, Iowa, a small agricultural town that became the unlikely new home of a Hasidic Jewish community, Stephen G. Bloom writes that he found himself "smack in the middle of an evolving conundrum." Everybody in Postville then knew that Bloom was himself a Jew (although not a Hasid), and four years after moving his family to the Hawkeye State he had also become an Iowan. The combination, he believed, made him uniquely suited to understand the slow-brewing conflict between the black-hatted, black-coated newcomers in payot (curled side locks) and zizit (tasseled tunics) and the stolid prairie farm families around them. "Neither group took my roots to be deeply sunk in either legacy," Bloom writes, "but ... I felt an obligation to understand the Jews and the Iowans and the slippery nexus that bound them to each other."

In 1987, six years before Bloom came to Iowa, a Russian-born butcher named Aaron Rubashkin bought a defunct slaughterhouse just outside Postville (population 1,478). Rubashkin was a Lubavitcher, a member of the ultra-Orthodox Hasidic sect based in the Brooklyn, N.Y., neighborhood of Crown Heights. In a state where pigs outnumber humans five to one, Rubashkin built a glatt kosher meatpacking plant (i.e., one that conforms to the strictest possible dietary standards), which soon became the largest such Lubavitcher-owned enterprise anywhere in the world. The plant brought an unexpected new era of prosperity to Postville, whose farm-based economy had been struggling for decades. Although rabbis must supervise kosher slaughtering and packing procedures, some 350 jobs at the plant were open to gentiles. Furthermore, the arrival of several dozen affluent Hasidic families was a boon to the town's merchants, from the bank to the shoe store to the cleaners to the diesel-fuel cooperative.

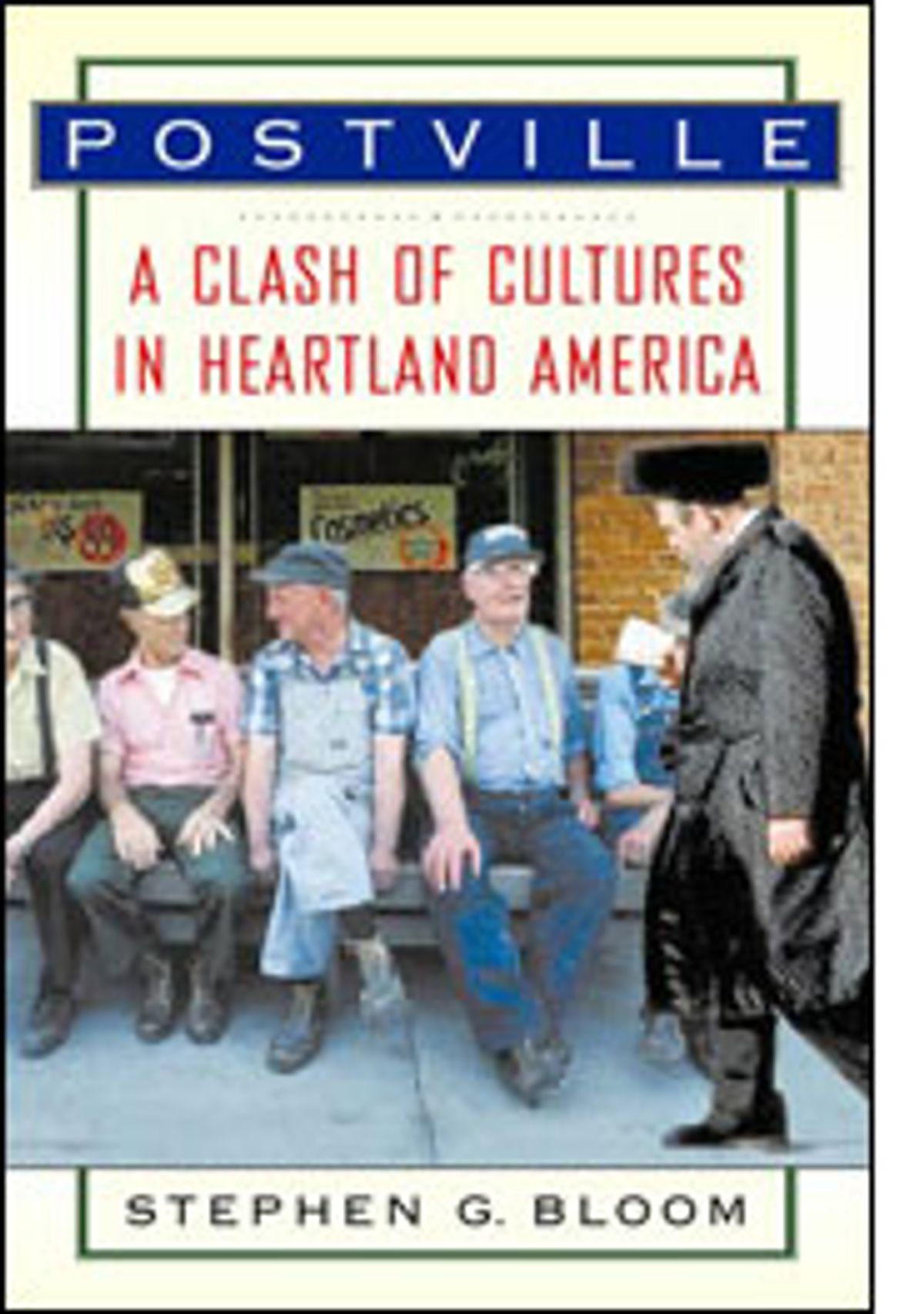

As the subtitle of Bloom's book -- "A Clash of Cultures in Heartland America" -- makes clear, the problems that arose in Postville were primarily cultural rather than economic. Friendliness and hospitality are core values in small-town Iowa, but the Hasidim, like the Amish or the Mennonites, are an insular community that is profoundly mistrustful of the outside world. Their religious laws and cultural mores combined to make social intercourse with the people of Postville virtually impossible. When they patronized local merchants they haggled over prices, a venerable Jewish tradition that the Lutherans of northeastern Iowa found both astonishing and insulting. In a town that prided itself on its impeccable streets and houses, the Hasidim never mowed their lawns or raked their leaves, and often drove battered clunkers that spewed oil and exhaust. (These issues had not come up in the apartment buildings and semidetached houses of Crown Heights.)

Bloom, a former reporter for the Los Angeles Times and other newspapers who is now a professor of journalism at the University of Iowa, is an able and sympathetic observer of both sides of Postville's cultural divide. He hangs out at Ginger's, the downtown coffeehouse, with a group of men in OshKosh overalls and John Deere caps, one of whom tells him, "I've dealt with Jews for a long, long time. And every time, they set out to fleece you. You can see it in their eyes." (It took the locals a long time to figure out that Bloom was Jewish, since most of them had never met any Jews except the Hasidim.) He uses his faith to gain access to a Hasidic household on the Sabbath, accompanying the family to shul (synagogue) and its male members to the mikvah (ritual bath). At the latter, he envisions a place of spiritual cleansing and epiphany but finds only a tank of stagnant, dirty water under a naked light bulb.

By the time Bloom shows up, the Postville locals are contemplating a ballot measure to annex the land where Rubashkin's slaughterhouse sits, which would make the plant subject to town taxation and regulation. Rubashkin's son Sholom, who manages the operation, has denounced the ballot measure as anti-Semitic and threatens to close down the plant and move elsewhere if it passes.

Both the strength and the weakness of "Postville" lie in the fact that the book is less about this small town's conflict between Jew and gentile than about a version of that same conflict happening inside Bloom himself. Bloom is always honest about his mixed emotions toward the Hasidim and the locals, and is jovial and self-effacing when discussing his failed efforts to blend in with either group. His prose style is awkward and his philosophizing often simplistic, but even those qualities add to the sense that he is an Everyman trying to find common ground between the intractably opposed communities.

A secular Jew who had lived most of his life in urban centers of the East and West Coast, Bloom writes that he felt isolated after his first few years in the heart of Christian America. His son's Cub Scout leader talks unthinkingly about Jesus, and the Easter Sunday headline of the Cedar Rapids Gazette reads: "He Has Risen." (Bloom jokes that this "broke all the rules of news judgment that I preached to my journalism students. The event was neither breaking news nor could it be corroborated by two independent sources.") Although he had never been religious, he saw the Postville Hasidim as a chance to reconnect with his own fading sense of Jewish heritage and pay a cultural debt he owed his son: "It seemed essential to nurture our Jewish souls," he writes, "the sense of who we are, how we think, where we come from." By his own admission, he was craving his Miami grandmother's matzo ball soup and brisket more than a spiritual awakening; he imagined the Jews of Postville as "a hermitage of wise men" who "would brighten my soul with witty talk and warm my belly with nurturing food."

Eventually Bloom and his son, Mikey, do eat a lavish Sabbath dinner (Hasidic women can do little besides cook and clean house), but it comes at a price -- they become the targets of the Hasidic community's evangelical zeal. (One of the sect's primary goals is to bring nonobservant Jews to the true path.)

"Postville" is full of fascinating detail, and Bloom does a fine job of both explaining the Hasidic worldview and exploring the textures and rhythms of Hasidic daily life. But his decision to put his own internal struggle at the center of the book is finally a serious flaw -- and a curious one, for a trained reporter. He has neither the writing chops nor the intellect to make this agonized introspection interesting (in fairness, Jewish readers wrestling with their own spirituality may find it more engaging than I did), and his self-obsession nearly blinds him to what's really happening in Postville. The only thing the Hasidim and the town's old-timers agree on is that neither group wants its community to change, but that's the one thing neither group can have.

As Bloom only half-recognizes, the once-homogeneous world of Postville has been radically transformed, in ways that are startling to all sides and not always pretty. Two young Hasidic men go on a crime spree and shoot a convenience store clerk. Immigrants from Mexico and Ukraine show up in large numbers for the low-paying slaughterhouse jobs. A Lubavitcher woman leaves her husband and is seen at a football game with a local man. The annexation issue fades into insignificance. The people of Postville, new and old, Jew and gentile, are Americans after all.

Shares