Alan Moore spun a tornado into motion 14 years ago, and now he wants to repair the damage — with a talking gorilla.

In 1986 the legendary comic book author changed the genre forever with “Watchmen,” a 12-part serial in which superheroes turned rapists, racists and flunkies of Richard Nixon are hunted down in the days before World War III. This series was read by people who’d never read comics before and never would again. It influenced a generation of comic book writers to turn cowled and caped men into emotional invalids who were fighting crime in lieu of substantive psychotherapy.

It was also what turned Moore into the medium’s first pop star, bigger than the characters on the page. Now, he is using that status on his latest endeavor: a whole line of comics meant to reconstruct the superhero, to make him and her again worthy of our attention.

This is not just an aesthetic concern. Having established the “direct market” in the 1980s to better serve the existing readership, giving comic shops earlier access to books than newsstands, the comic book industry set out on a decade-long pursuit of self-destruction. Between 1990 and 1993, the number of comic shops in North America rose from 3,000 to 10,000, fueled by customers’ misguided hopes of financial reward. Forty-eight million comics were sold in April 1993, helping sales for that year to reach $850 million.

Sales booms, when based on products largely inessential to our own breathing, invariably end. By January 1994, 1,000 comic shops, or a 10th of all such stores in North America, went out of business, followed by 11 of the 12 distributors set up to serve them. Marvel, the home of Spider-Man and the Hulk, which had collected revenues of $415 million in 1993, saw its stock lose 90 percent of its value, forcing the company to file for Chapter 11. Last year, the industry as a whole averaged about 7 million copies a month in sales.

More troubling is that comics lost their sense for self-preservation. They became the nearly exclusive domain of specialty shops, they grew exorbitantly expensive compared with other forms of entertainment and their story lines relied on 10 or more years of previous reading for one to understand. Once, we came to comics early in life, still able to believe in a scientist from a doomed planet delivering us a boy who could change the course of rivers and outrun bullets. Without that early exposure, the form that gave Clark Kent life has become the one in need in saving.

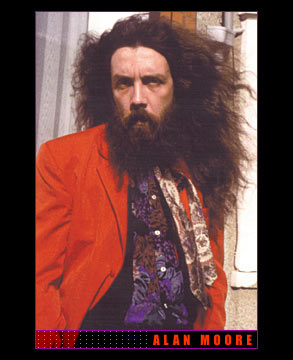

Waiting for Moore in the lobby of the Grand Hotel in Northampton, England, I’m prepared to be scared. This readiness comes from nothing other than an unnerving examination of his publicity photos, the most haunting of which depicts Moore leering up at the camera, his long beard flowing into darkness, with only the left side of his face visible, as if he’s hanging off the perch of a benighted void. Moreover, I know that he makes no personal appearances, doesn’t associate with “fan boys” and doesn’t attend comic book conventions. He takes a scant view of TV appearances and very rarely leaves the country.

So I’ve flown from my home in Chicago to London, then taken a train for an hour and a half across the English countryside to a place only 68 miles from the U.K.’s social and political heart but, at first glance, as foreign and removed as Guam. Established by the Saxons in 700, it’s a factory town, but all cobblestone at its center. It’s the kind of place where the fading limestone and weathered arches of the All Saints Church look across the street to an electronics shop, a community where it’s difficult to find anyone under 30 after dark. Leave your window open at night and you hear post-pub-closing romantic quarrels and fisticuffs until 4 in the morning.

All of this leaves me with what Harper’s editor Lewis Lapham once described as the “desperate innocence” of a true believer, willing to go any distance to sit near the feet of a near spiritual being. This is what “Watchmen” made of Moore in the eyes of comic fandom: the man who made comics that disapproving nonreaders enjoyed. An Alan Moore comic in hand earned you a bit of redemption.

Set in mid-1980s New York, “Watchmen” asks what would have happened to us if costumed heroes had appeared in reality around the same time they appeared in the American pop consciousness: the 1930s. It shows heroes getting old and losing faith in the public, against the backdrop of an imminent nuclear war. The series received startling acclaim in Time, Rolling Stone and the Nation. A headline in the Chicago Tribune declared it “a comic book as gripping as Dickens,” but warned readers to “think twice before you show it to your kids.”

Moore, 6-foot-2, with hair way past his shoulders and a beard that appears to reach his chest, arrives. Yes, he dresses completely in black and carries a walking stick in the shape of a snake. He has thick metal rings on all his fingers, but also the air of a rosy-cheeked English barrister back from the Continent, waving his snake in circles as he talks, a storyteller trying to lay out the places he has seen on the map of his imagination.

Over lunch in a basement pizza parlor, Moore says that his current endeavor — “America’s Best Comics” (ABC) — came to him “almost mystically,” after the 1998 collapse of Awesome Entertainment, the publisher of his project “Supreme.” In thinking about what would come next, Moore opened up one of the notebooks in which he occasionally scribbles dialogue for his characters in longhand, and there he found a list of names.

Tom Strong. Promethea. Greyshirt. Jack B. Quick. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Top 10. He hadn’t remembered writing these, but they were in his hand. And it seemed to him that the names themselves had a certain degree of resonance, that they wanted to reflect an earlier time in comics history, before Superman’s creators, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, by accident really, changed America for good and forever.

Essence was what he was interested in here — taking just the plain nub of what makes superheroes appealing and “fusing it with a progressive sensibility — something that can be retrograde and avant-garde at the same time. So you get the best of what comics were, sort of distilled in some way to make the fuel for what comics will be.”

“Not,” he adds, “to sound too high flatulent about something that’s just a crap superhero book.”

Moore himself favors nonhero, small-press work to the dozens of books he receives each month in his “big box of shit” from DC Comics. He says he would prefer the diversity of comics in the 1950s, where one could find everything, from the most benign subjects — cowboys and Martians and funny animals — to the most morally aphasic characters, within the 24-page pamphlet. He would rather not write about superheroes, but he feels that he must do what he can to save the mainstream marketplace and, in so doing, embolden the only subject anyone in the mainstream has any interest in reading about.

In trying to pull the locomotive from peril, then, Moore has chosen to use all of his available hours to write and bring together a horde of artists giddy at the prospect of working with him. He produces five books, including “Tom Strong” and “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen,” in which Captain Nemo, Bram Stoker’s Mina Murray, Allan Quatermain, Henry Jekyll and the Invisible Man team up to fight the forces of darkness at the end of the 19th century.

In “Tom Strong,” Moore reaches for the hero at his most archetypal, trying to reel, as he puts it, “the tape of the superhero” back before Superman. In the tape before Superman are the pulp characters that inspired him — Doc Savage, Solomon Kane — as well as the charm and freshness of Tintin. Moore wanted Strong to have a Victorian origin but still be around today, wanted him married because “married superheroes are somehow sexier” and knew, in some way, that the hero should be friends with a talking gorilla.

What’s appealing about Tom Strong is precisely how unrealistic he is, how very little attempt there is to link him to the drudgery of daily life. Little if any concern is given to the fact that Tom is 100 years old and looks 39, or to the fact that, when called upon, he will be sent back into time and travel to Venus. Moreover, Tom Strong acts not out of a desire to feed his ego or a pathological need to hurt but out of what Plato, in his “Republic,” deemed “justice”: each person in a society performing the role to which he is most suited.

“He’s got a fantastic visual imagination, and no comic book writer ever tried to communicate that to an artist before,” says longtime Moore collaborator Rick Veitch. “What most comic book writers did was give you the most simplified, bare-bones description of an act that was supposed to take place on a panel, like ‘Superman fights Bizzaro,’ [whereas] Alan goes into the motivations of all the characters while they’re doing that. He’s setting up tiny little images, telling you, ‘Oh yeah, there’s a picture on the wall back there of Bizzaro when he’s a young kid.’ He’s tracing it in all these different levels — and some artists can’t handle that.”

“I’m not interested so much in whether they’re clever or profound,” Moore says of his comics. “If they happen to be occasionally, fine. But I’m mainly concerned with whether they’re fresh or not. It’s just been kind of stale — ‘For Christ’s sake, will somebody open a window?’ — for the comics industry for 10 years. I just wanted a bit of fresh air.”

After lunch Moore and I walk around the streets of Northampton. He seems out of place here, though he has never really been anywhere else. Born here in 1953, he was raised in a neighborhood with houses from the 19th century, owned and rented out by the Town Council. The maternal grandmother with whom he and his family lived had no indoor toilet, while his other grandmother had indoor plumbing, all right, but no electric light.

“Looking back on it,” he says, “it sounds like I’m describing something out of Dickens. I mean, I’m talking 1955, but 1955 in England. I’ve seen ‘Happy Days’ on television. Maybe the American ’50s were like that, but that wasn’t what the British ’50s were like. It was all sort of monochrome, and it was all indoors.”

The escapes Moore found were all in the form of imaginative forces — in mythology, first, with the children’s versions of the Greek and Norse legends, the children’s Robin Hood and Hiawatha. There were comics, of course, but these were British comics, works that depicted the travails of uniformed boys in public school. Black and white, they focused mainly on jokes about headmasters and corporal punishment, and appeared to Moore then not as an escape but as a cackling mirror of the problems he faced.

Then came Superman and the Flash — modern-day extensions of his beloved myths. And they were even more fantastic for their presence in America, a place drawn in color, with huge buildings Northampton just couldn’t offer.

“I got my morals more from Superman than I ever did from my teachers and peers,” he says. “Because Superman wasn’t real — he was incorruptible. You were seeing morals in their pure form. You don’t see Superman secretly going out behind the back and lying and killing, which, of course, most real-life heroes tend to be doing.”

After dealing acid (something Clark Kent might frown upon) and getting thrown out of school at 17, Moore traded his childish flights for grown-up rigor. He went to work at a sheep-skinning plant on the outskirts of town for 6 pounds (now equal to $8.66) a week, then cleaned toilets at the Grand Hotel, where we’re meeting. It was after moving up to an office job at the local gas company that he hit his crossroads: He decided that if he didn’t act soon on his more creative impulses, he’d have to face himself in the mirror when he was 40, and decide whether to slit his wrists.

In truth, he didn’t know exactly what he wanted to do. So he went on public assistance and, with a pregnant wife, spent a year starting impossibly big projects (a 20-part space opera, of which he wrote only a page, for example). Finally, he got work as a cartoonist for British music weekly Sounds.

His work became known in British comic magazines Warrior and 2000 A.D. In 1984, DC Comics tapped him to take over one of its least successful books, “Swamp Thing.” Unconventional and serious, he turned the book into a tool for exploring social issues, using it to discuss everything from racism to environmental affairs. In return, he quickly drew a devoted following and raised the monthly sales of the comic from 17,000 to 100,000 copies.

“Nobody,” he says, “wanted to actually say, ‘But he’s talking rubbish.’ They all sort of said, ‘He’s an English genius, and you must be a fool if you don’t see it,’ which did me well for a while.”

After “Swamp Thing,” everyone saw the genius with “Watchmen,” which, along with Frank Miller’s “The Dark Knight Returns,” a depiction of Batman’s older, alcoholic, calamitous self, spawned a slew of imitators. For the better part of five years, every book seemed to feature deconstructed bad guys turned mildly good who, dredged up from the sewers, say very little and kill very readily.

Having become the comics’ first “star writer,” Moore was mobbed at conventions and asked to appear on TV, and he soon swore off both. He and artist Dave Gibbons fought with DC over money. Then DC, in response to evangelical pressure, slapped some of its titles with “Mature Readers Only” labels. In response, Moore walked away from DC, from “mainstream comics” and even from superheroes forever.

Moore threw all of the “Watchmen” money into his own publishing company, and began his ill-fated magnum opus. It was called “Big Numbers,” and it was supposed to be a 12-part, 480-to-500-page work, with 40 characters. The script was huge. Moore, his wife and their mutual girlfriend would spend whole days photographing scenes for long tracking shots that were meant to last for four or five pages.

Our most ambitious endeavors are the ones most prone to great failure. Artist Bill Sienkiewicz started turning in his artwork later and later, and then quit after the second issue. His replacement, Al Columbia, worked on one issue and then disappeared. In the course of things, Moore’s marriage ended, and he lost nearly all of the money he’d earned from “Watchmen.”

“I don’t think it was misguided at all,” says Gary Groth, editor of the Comics Journal. “I think it was the best thing Alan could have done — for himself and for comics. That it failed was a real tragedy.”

Moore’s response was to return to the superhero, but not through the same door. He now believed that talking about an issue such as the environment in comics was perfectly all right, but using a swamp monster to do so trivialized the matter. Moreover, by attaching a self-consciousness to superheroes, a belief that they had to be grounded in what is often an awful reality, one was throwing away their fundamental greatness: the uncanny ability to lift our spirits, to bring us closest to the primordial setting of the storyteller “sitting around the campfire, making up impromptu stories about the guy who can fly.”

Moore’s reclamation project began in 1996, when he took over a “very, very, very, very, very” lame superhero named Supreme. Created by artist Rob Liefeld, Supreme had been drawn and written as a brooding, musclebound oaf, a crusader who said largely incomprehensible things like “Foolish pup! Back to your mother!” Moore threw away this severity by refashioning the hero’s origin and recycling elements that had been discarded by DC Comics’ various Superman revisionists. He filled the book with silly, wonderful components, and converted the central character into a moral paragon. Supreme was the jumping-off point for Moore’s current idea of saving the comics industry, one that has led him back to the financial auspices of DC. By August of 1998, Moore had begun work on a major project for Wildstorm Comics, developing story outlines and commissioning artists, when he received a visit from then Wildstorm owner Jim Lee and the company’s editor in chief, Scott Dunbier. Over lunch Lee told Moore that because of the instability of the market, he had agreed to sell Wildstorm to the behemoth Moore had walked away from more than 10 years before. Moore thought about dropping the project altogether, but he was reassured that he’d be working directly under Wildstorm’s editors in California, not those at the Time Warner (DC’s parent company) building in New York.

“Alan’s got as much input as he wants,” Dunbier says. “He will always have as much input as he wants. But he trusts us. I mean, he trusts us a lot more so than a lot of other publishers.”

It’s hard to say whether all of Moore’s efforts will succeed. Retailers have complained that the ABC books are consistently late, and in February, the seventh issue of “Top 10” ranked 59th, with 32,000 copies sold on the direct market, while “Promethea” had sold 29,000, good for 70th place. These numbers are profitable, but they’re nowhere near good enough to resuscitate comic shops that have taken to selling toys, memorabilia and even adult publications to stay afloat.

“Did Alan say he’s trying to save comics?” asks Groth, who loathes superhero comics and has yet to read any of Moore’s ABC books. “Good lord, it sounds like desperate hyperbole. Why would anyone want to save mainstream comics?”

There are many things about the industry Moore cannot change. All he can do is hope for new fans, and hope that the old ones who watched him take apart the superhero 14 years ago will return to see the myth reassembled.

“What I could do is what everyone wants me to do,” Moore says over coffee, having come back with me to the lounge of the hotel where he once scrubbed toilets, “and to ignore the fact the popular market is going down the toilet. I could do something really obscure. I’d get critical appeal and sell 1,500 copies and incidentally go broke and earn the respect of Gary Groth, and the comics industry would completely fall to pieces. Even if it all happens, and comics does fall to pieces, at least I did my best.”