The driver pulls up our Town Car to the front of the Queens Borough Elks Lodge No. 878. This is the site where James Gray wanted to film one of the final scenes in his new "corruption in the system/strife in the family" movie, "The Yards."

The Elks wouldn't allow Gray to shoot in the lodge, so he filmed the scene elsewhere, but he wants to show it to me anyway. We walk up the front steps of the building -- a gray stone monolith on Queens Boulevard in Elmhurst -- and that's when we hear the bagpipes.

The bleating becomes louder as we follow the sound up a set of inside stairs. On the second floor of the lodge, in a large, gymnasium-like hall with vaulted ceilings, we find the New York Fire Department's Emerald Society Pipe and Drum Band practicing. "This is so great!" says Gray, barely able to contain his joy at happening upon something so surreal at 7:30 on a Monday night in Queens. "I'm serious. I can't believe this!"

The 31-year-old filmmaker is like a little kid, excited by what he's seeing. Which is this: a bunch of burly men, dressed in jeans and T-shirts, manipulating ancient Scottish instruments, honking away at ungodly decibels. That the Emerald Society is, in fact, a band at all is a matter of faith, since each member is practicing his own chords (or whatever bagpipe notes are called) at the moment.

But Gray is deferential around these men as they wander back and forth through the lobby outside the hall. He keeps his distance, speaks only when spoken to, is overly polite. To Gray, these blue-collar guys, who go to work each day and do a dangerous, thankless job, deserve respect. They are heroes, and heroes are not to be trifled with.

But his filmmaker's sense -- that signal that goes off when a scene might be ripe for the telling -- loves the incongruity of large New York firemen heaving away at bagpipe practice.

James Gray is flummoxed

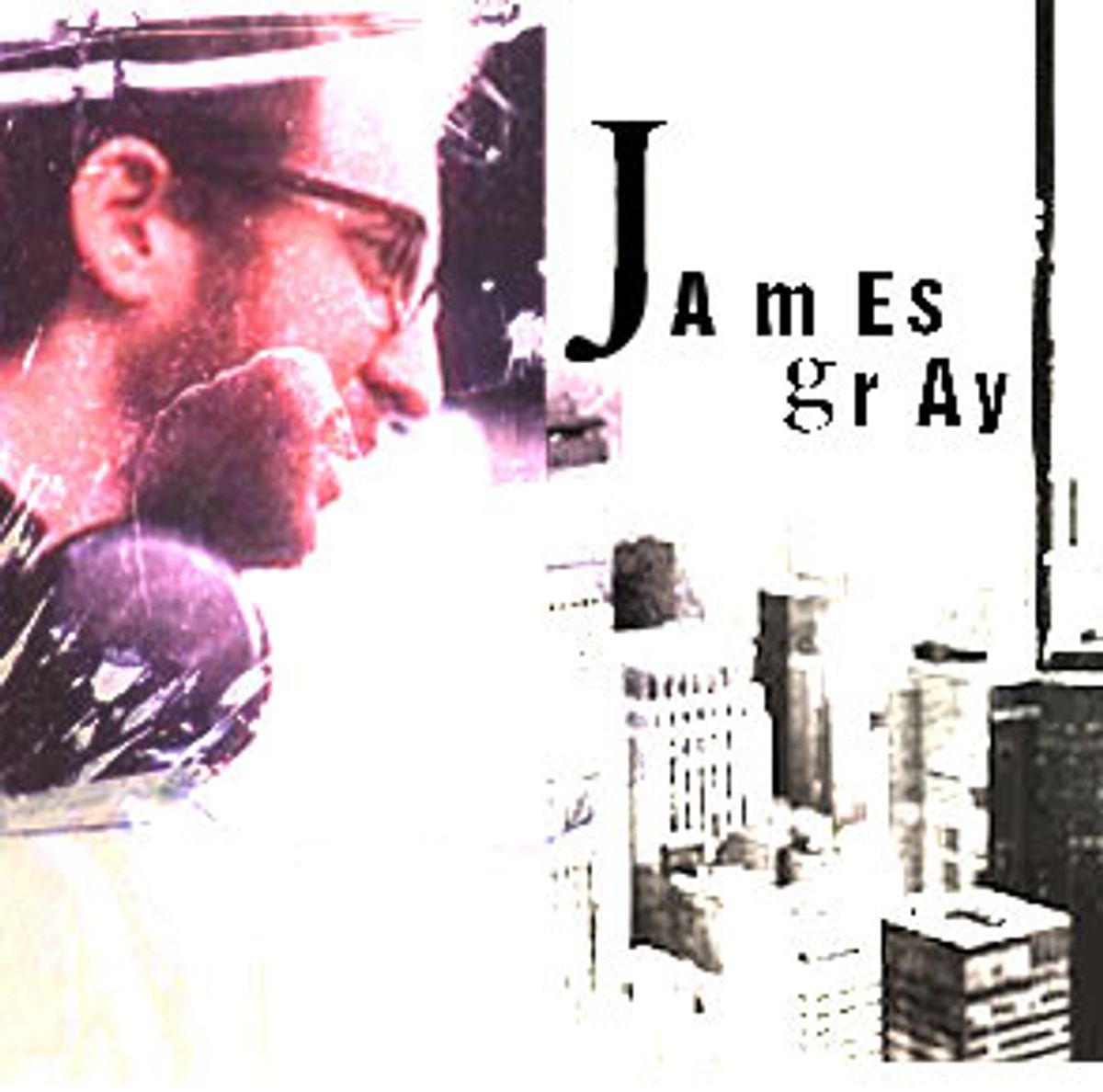

Back in Manhattan, when Gray and his publicist pick me up at my apartment, the director begins talking before I'm even sitting in the back seat. Gray has just flown in from the Toronto International Film Festival, and is dressed all in black. He has a tall, blond pompadour and long sideburns and he wears horn-rimmed, tortoise-shell glasses. He's wearing a leather jacket, but he's ready to explain it away, as if it might be offensive to someone who lives in New York.

"We were in Toronto and this woman from the Gap comes up to me and says, 'You must come by the store tomorrow,' and so we did, and we get there and she tells me to pick something out," he says. "I pick out a shirt or something and she just starts throwing stuff at me: 'Take this, this would look nice with that shirt; and here, have a jacket; and try on these pants.' I thought I was going there for a shirt, and I walked out of there with, like, $3,000 worth of clothes. I'm just a blue-collar Jewish boy from Queens -- what do I know?"

Why, he wondered, would the Gap give a young, critically acclaimed film director on the verge of releasing his second movie a bunch of clothes for free? Could he really be that naive? It's doubtful. James Gray has seen things.

Gray, a "strange kid" by his own account, was brought up in the Flushing section of Queens. He was lonely and not very good-looking. The only things he cared about were the movies and the Yankees. High school girls were not swooning for the 6-foot-2, 135-pound kid with braces and bad skin. School, in fact, wasn't really his thing. Nor was reading, so he'd play hooky and go to the movies -- sometimes seeing two a day.

One theater played strange afternoon double features. "You could see "Bringing Up Baby" and then "Fitzcarraldo," he says. He remembers seeing "Apocalypse Now" and "Raging Bull" during a time he now calls "the last gasp of American cinema," and being mesmerized. He began seeing films by Fellini, Kurosawa and Visconti. And then he got into the University of Southern California Film School.

But even at USC Gray was different. He liked the "arty" directors, while his classmates were into Steven Spielberg. Gray took classes in film theory and history; he took film production classes to learn about different lenses. He made a short film about "sexual discontent," which got him some attention and an agent. After he graduated he looked for something to direct but couldn't find anything he liked, so he decided to write something himself. He sought plot, characters and tone back east in New York.

"Little Odessa," the story of a hit man who comes home to his Russian Jewish émigré family in Brighton Beach, was released in 1995 and won the second-place Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival. Playboy called "Little Odessa" "impressive" and "poetic," Newsday said it was a "stylishly dark and detached drama" and the New York Times said it was the beginning of a "powerful career." Not everyone was as moved, however. The Portland Oregonian wrote, "Gray offers precious little that audiences aren't bored with already," and Stanley Kauffmann of the New Republic called the film "a pointless, predictable clinker."

Immediately after "Little Odessa," Gray started working on what would become "The Yards," telling the Village Voice, in 1995, "It's my 'Rocco and His Brothers,'" Luchino Visconti's 1960 film about a family member returning to the fold and brothers who become enemies.

"The family," Gray told the Voice, "is not always a place of joy and comfort; it can be deadening and horrific."

James Gray is troubled

We are wandering through the train yards in Queens, the location of the pivotal scene in "The Yards" in which Mark Wahlberg, who plays Leo Handler, the prodigal son, has no choice but to beat a cop nearly to death. Leo has returned to the old neighborhood after being released from prison, where he took the fall for a group of his friends. Leo wants to get his life back together. He approaches his connected uncle (who came into the family while Leo was in prison, and who runs a company that repairs subway cars) and asks for a job.

Uncle Frank (James Caan) tells Leo he needs a couple of years of training and sends him on his way. This isn't good enough for Leo, who needs to support himself and his sick mother (amazing Ellen Burstyn), so he hooks up with old friend Willie Guitierrez (Joaquin Phoenix), who does some "alternative" work for Uncle Frank. The cast is rounded out by Faye Dunaway as Uncle Frank's wife, Kitty, and Charlize Theron as Leo's cousin and Willie's girlfriend. Bad things happen when Leo -- out on parole -- is asked to take the fall again, this time for something he didn't do.

The story is a combination of family dysfunction and corruption in the subway yards, and it's ripped from painful moments in Gray's own history. Standing in the yards, the director asks me not to write about the particulars, but says that the events are closely tied to actual events in his family saga -- his mother's fatal illness, his father's involvement with corrupt politicians.

Much of "The Yards" is accurate, down to details as small as postcards taped to the walls of lower-middle-class Queens apartments and illegal payoffs done in the nude (to be sure no one's wired). That "The Yards" is billed as a work of fiction might be the biggest fiction in the film, and Gray is worried that when the movie comes out, so will too much information about its origins.

Indeed, the New Yorker's Tad Friend did some digging and, in an Oct. 13 "Talk of the Town" piece, uncovered what Gray told me in the yards. Friend writes that in the early '90s, the government charged Gray's dad (who owned an electronic parts company that supplied New York's Metropolitan Transportation Authority) and his partner with bribing an MTA official.

Gray is worried about having made such a personal, intimate film -- which lays some painful family truths on the table for the world to see. He's worried his dad will be hurt by it all, and about what he'll think of the film itself (though his father read the script, and suggested changes for the sake of reality) -- if he even decides to see it.

James Gray is furious

"I'm so fucking miserable!" Gray is furious because he has promised to treat everyone in the car at Eddie's Sweet Shop, which serves, according to Gray, "the best fucking ice cream ever." For blocks, he has been talking about how wonderful this place is -- the flavors, the textures, the cones. He has built it up for us (and for himself) big time, so when we pull up to the small corner store and it's shuttered (closed on Monday nights), Gray is disappointed -- for us and with himself.

I don't want to make too much of the Eddie's Sweet Shop incident, but it does convey a little bit about Gray's expectations. He wants always to please, and he has raised the bar high for himself and for his work. He compares what he does, or at least what he's striving for, with opera, with art. If "The Yards" feels melodramatic and clichéd at times, that's because Gray is trying for nothing less than capturing the zeitgeist on film by channeling Greek mythology and its progeny. He wants to tell his generation's versions of Homer, Shakespeare and Zola.

And movies are the way to tell those stories at the turn of this century. Directing is more than "a guy with a folding chair, a black beret and a paper megaphone," Gray says, walking outside the Juniper Elbow Co. -- another building that inspired scenery in "The Yards." "Movies are the most direct path to doing something emotional."

A muscular Rottweiler prowls inside Juniper's chain-link fence. So many jets fly above us, coming into and leaving JFK Airport, that they seem more like mosquitoes we could swat away if need be. Gray is talking about Wahlberg's character and the "classic tragic structure" of his movie.

"Tragedy is when a character knows or believes his life is not in his hands," he says. "That's true of Leo. His life is out of his control when he gets out of prison. What he wants is control of his life back, but that doesn't happen -- things continue to spin out of his control. His life is unraveling and he can't do anything to change it. Ultimately, he takes control back by seeking help from the legitimate system. Which is all he wanted to begin with."

At one point, while we're walking outside Lutheran Cemetery, opposite the Juniper Elbow Co., he stops.

"Do I sound like an ass?" he asks. "Seriously, tell me when I sound like a pretentious prick. Make me stop."

He continues talking about Wahlberg's character, but he could just as easily be talking about his own obsession with the movies and his career as an independent-minded director in Hollywood trying to imitate his childhood heroes.

"His fate is in the destiny of the system at large," he says. "It was dictated to him from moment one."

Shares