Philip Kaufman's "Quills" is like an elaborate 18th-century woodcut come to life. It's a picture puzzle that offers a dazzling and provocatively brainy message on the surface only to reveal, on closer inspection, an erotically charged cluster of characters fumbling, fondling and fornicating. They're living in the roughest and most passionate way, committing acts that stretch beyond our boundaries of approval or disapproval, whether we're libertines or prudes or anything in between.

Based on Doug Wright's play (Wright also wrote the screenplay), "Quills" is a delectable and ultimately terrifying fantasy about the last days of the seductively malignant Marquis de Sade (Geoffrey Rush). It's the early part of the 19th century; Sade has been imprisoned in the insane asylum Charenton for some unspecified crime. (In real life, Sade was imprisoned on and off throughout his lifetime for crimes ranging from debt to sexual deviancy, often because of the machinations of his mother-in-law.) His confinement hasn't kept him from publishing his scandalous texts, smuggled out of his shabbily lavish prison cell by the voluptuous and winsomely game laundress Madeleine (Kate Winslet). Meanwhile, the lovesick Abbé Coulmier (Joaquin Phoenix), who oversees the asylum and considers himself Sade's friend and protector, looks the other way.

When the Emperor Napoleon gets ahold of one of the smuggled texts, Sade's blasphemous and pornographic "Justine," he packs off a specialist physician, the panther-cruel Dr. Royer-Collard (Michael Caine), to "cure" Sade of his perversions, or, rather, to keep him under strict control. Sade, who immediately pegs Royer-Collard as a less-forthright mirror version of himself, resists. The doctor's persecution spurs him on, until one of the tales he spins from his prison cell inspires and incites a tragic and supremely horrifying act.

The movie has already been praised by some critics as a vigorous anti-censorship treatise, but that makes it sound so much drier than it is, and it captures only one small wave of the movie's resonance. "Quills" is a complicated picture. Its multiple themes crisscross and swell and recede, and the ending leaves us in a place very different from where we started. Rife with rampant obsessions, necrophilia and murderous sexual acts inspired by a writer's prose, "Quills" is a story about the uncontrollability of passion and of art. It's an allegory of sorts, but it's one with blood coursing through its veins. The movie's lessons skitter flamboyantly across its surface -- the actors hand them to us baldly in the dialogue. "If I wasn't such a bad woman on the page," Madeleine tells the Abbé, who has also fallen deeply but chastely in love with her, "I couldn't be such a good woman in life."

"Quills" is also a call to action, a reminder that art has to be allowed to breathe if it's going to flourish. But it also sets on its ear the idea, held dear by plenty of liberals and conservatives alike, that art's grandest purpose is to enrich the world. If art needs to incite passion to be effective, then, given the unpredictability and uncontrollability of human beings, there's also the possibility that it might foster madness. The ugly truths behind the nature of art are no less valuable than the gorgeous ones; the notion of art's ability to elevate us is meaningless if we don't also accept that it's sometimes red in tooth and claw.

That could be a leaden theme, but not in Kaufman's hands. What makes "Quills" such a marvel is the chiffon lightness of its first two-thirds. The picture skates along merrily, even as its treacherous undercurrents gather momentum. Kaufman, the most catlike of directors, wants to play with us a bit before he slaps his paw down, but he stops well short of being sadistic: He makes sure the game is as wickedly enjoyable for us, his prey, as it is for him.

Even more important, Kaufman doesn't sacrifice the picture's characters on the altar of the picture's mission. They're always the ones -- with their florescent perversions, their wayward desires, their devilish or angelic beauty -- who drive the movie. When Dr. Royer-Collard orders that Sade's paper and writing implements be taken away from him, there's mischievous merriment, bordering on a mad scientist's delight, in the way Sade discovers that red wine can be used as a substitute for ink. Before long, he takes more pleasure in his ingeniousness than he does in the act of writing: You can see it in the way he flutters his crudely bandaged fingers like raggedy war-torn butterflies, having drawn his own blood to fashion yet another of his immodest and immoral tales. Those bandages are less like badges of his dedication than works of art in themselves; like the Catholic sacraments, they're outward symbols of Sade's obsessiveness, a physical counterpart to his maddeningly repetitive tales of sodomized virgins and flagellated buttocks.

"Quills" doesn't elevate the art of Sade; it actually goes out of its way to poke fun at the themes the real Sade embroidered and re-embroidered (among them his intense anal fixation) throughout his career. At one point the Abbé, who considers himself Sade's friend and protector, takes the writer to task for his "endless repetition of words, like 'nipple' and 'pikestaff.'" But the movie doesn't shrink from acknowledging the timeless power of Sade's work, either. When Dr. Royer-Collard's young bride Simone (played by the radiant and sly Amelia Warner), whom he's recently snatched fresh from the convent, pastes a copy of "Justine" between the covers of her "Lady's Garden of Verse," it's a reminder that no one is immune to ruthless seductions -- in fact, the innocent are the seducer's most coveted and perfect audience.

This Sade, as Rush plays him, practically quivers with evil elegance; he's an erotic crocodile in shredded finery, a creature whose lavish lifestyle and brutish hedonism aren't just remnants of his past but tinctures that have seeped into his soul. Rush gives us a more sympathetic Sade than the real-life one, who consorted almost exclusively with prostitutes, considering them lesser beings and therefore more suitable for his brutal games, like whipping a woman and then pressing hot candle wax into her wounds.

But Rush's slipperiness is still far from benign, and it's also treacherously appealing. When Madeleine comes to his door, he whispers a raspy order: "Go ahead, you've a key; slip it through my tiny hole!" And even well before the movie's final third, when Sade can't avoid facing the consequences of the tragedy that springs to life from his prose, Rush wins our sympathy for his character: When the Abbé takes Sade's pen and ink away, he crumples to near helplessness, stating flatly, "I'll die of loneliness without them."

Rush's Sade is the sun king of "Quills," but the subjects that revolve around him are almost as luminous. Caine's Royer-Collard is something of a stand-in for Ken Starr, a man whose smug sanctimoniousness is just a convenient cover for his own rotting soul, but Caine puts just enough shading into the performance to keep it from being a caricature. His particular brand of evil has the placid creepiness of a weeping willow.

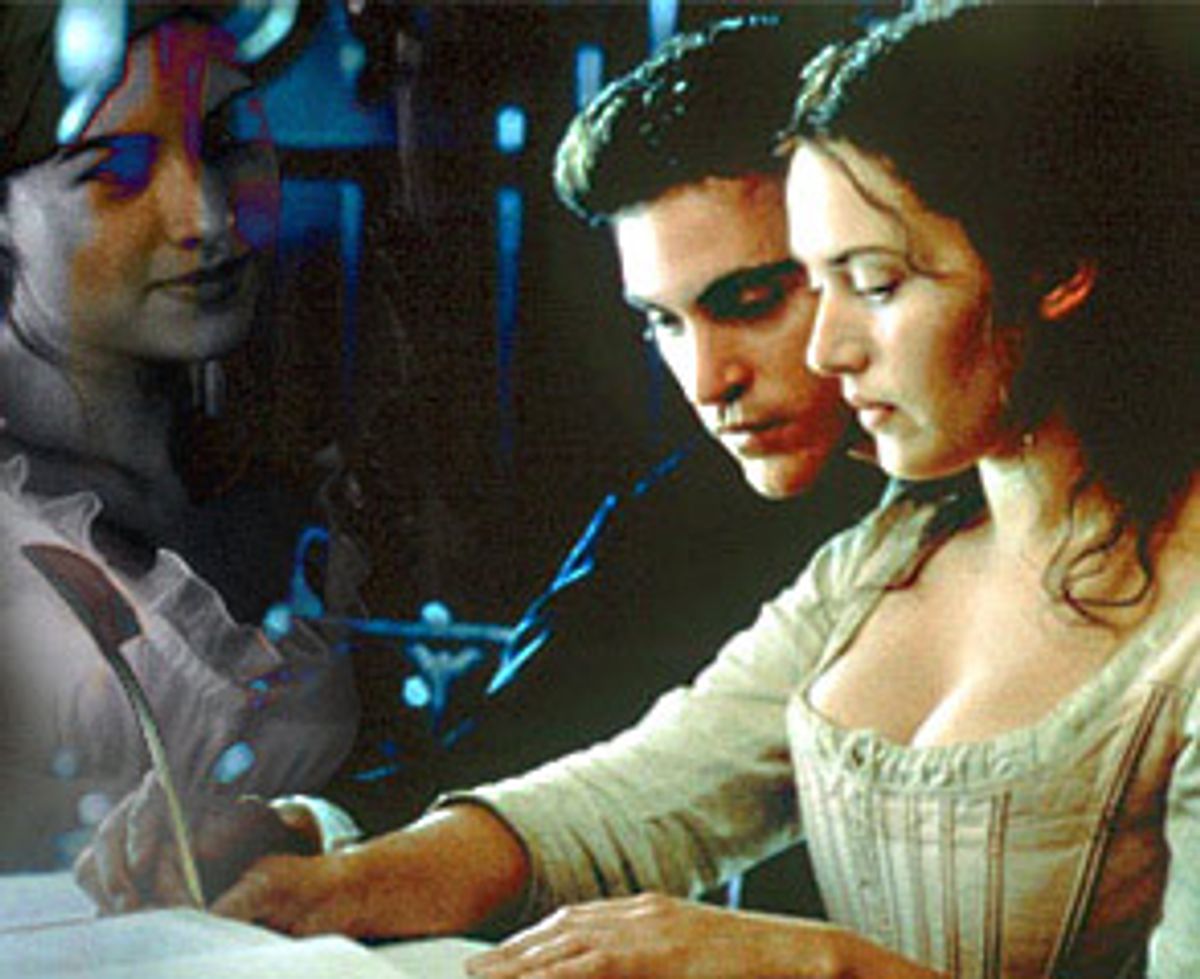

Phoenix's Abbé radiates so much purity and goodness that he invites us to laugh at him: Going around the asylum's art room, he stops at one inmate's florid, flaming painting and notes encouragingly, "It's far better to paint fires than to set them, isn't it?" But before long he's less a comical figure than a tragic prisoner himself. Even the set of his shoulders, girlishly narrow-looking in a fitted cassock, suggests a man who doesn't dare face up to his own decidedly masculine passions. His scenes with Winslet's Madeleine have a shapely delicacy: The two of them are almost girlish together, but Phoenix never lets us lose sight of the Abbé's repressed desire. Sade's virility is a gaudy music-hall show; the Abbé's is more muted but no less genuine.

And Winslet, flirtatious, conspiratorial, maidenly even at her sauciest, is pure delight. Sade is, of course, in love with her, in his own twisted way. ("You've already stolen my heart, as well as another organ south of the equator," he assures her.) When she creeps into his cell to procure a manuscript, he holds it away from her, telling her she'll have to pay a kiss for every page. When she obliges, it's clear she's half turned-on. But she's more of an accomplice to Sade, a partner in crime, than a lover. She reads his prose aloud to her friends ("Her flaxen quim! The winking eye of God!") with voracious joy. With her eternally flushed cheeks and excitable curls, Winslet embodies the thrill that art, at its best or its most devious, can bestow on us -- a suggestion that the excitement is sometimes more valuable than the work itself.

For all its audaciousness, "Quills," shot by Rogier Stoffers, with production design by Martin Childs, is a startlingly elegant-looking picture -- its surface has a faded, silvery sheen, like the frazzled brocades Sade wears in his prison cell. It's an unapologetic dazzler, which is why it's never overwhelmed by its themes.

At the heart of "Quills" is the idea that although art doesn't have to be dangerous to be effective, if it isn't allowed to encompass the possibility of danger, it's impotent. As Sade explains to some of his fellow asylum inmates before they're about to perform a play he's written for them, "Inside each of your delicate minds, your distinctive bodies, art is waiting to be born." All it needs is the right midwife to draw it out. How lovely, when the agent is Monet with his water lilies or John Donne with a blushingly romantic couplet. But it might just as easily be the Marquis de Sade, crooking his finger -- even as he ponders just which hole he'd like to put it in next.

Shares