In the midst of Gillian Armstrong’s lovely film of “Little Women” there’s a great, seemingly incongruous moment when Winona Ryder’s Jo blurts out, “I rather crave violence.” The craving marks Jo as the spoiler in her good pacifist family, but violence is at the heart of everything that rips you up in the story — the return of the March girls’ father from the Civil War, and especially the death of Jo’s younger sister Beth. There are no explosions or gunplay in the movie. But as with almost anything that affects us in art, the scenes do violence to our emotions, affecting us more deeply and more lastingly than any anonymous action-movie mayhem ever could. Jo craves transforming, earthshaking emotion. She pursues it in the pulp serials she writes of duels and damsels in distress, but she also finds it in the less sensational (but more affecting) story of herself and her sisters, the story that Jo/Louisa May Alcott goes on to write.

It’s easy to imagine the greatest American movie artists feeling that Jo March’s story is theirs, too. Many of the best American movies have sprung from the pulp of westerns, science fiction, detective stories, adventure tales and horror stories. And like Jo, our filmmakers are forever trying to bridge pulp and art, trying to meld the excitement of the former with the depth of the latter.

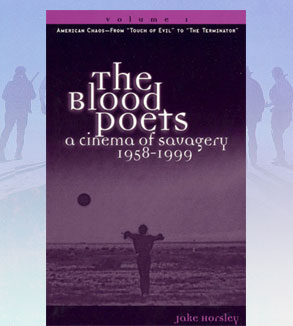

The debate about whether movie violence causes real-life violence (an argument I’ve never bought) has hijacked any exploration of how violence is actually used in the movies, how audiences experience it and when violence does or doesn’t qualify as art. Those are the questions that preoccupy critic Jake Horsley in his mammoth two-volume “The Blood Poets: A Cinema of Savagery 1958-1999.” Horsley arrives on the scene with a combination of articulate analysis and a provocateur’s punch. As with all audacious undertakings, the quality is highly variable. Over the course of nearly 1,000 pages Horsley is both thoughtful and polemical, specific and vague, rigorously logical and embarrassingly fuzzy, nobody’s fool and a sucker.

But Horsley dares to place violence, and the appeal of violence, at the heart of what movies are all about. “If you’re afraid of movies that excite your senses, you’re afraid of movies,” wrote Pauline Kael in “Fear of Movies,” her great attack on squeamishness as a basis for aesthetic judgment. Horsley goes further. “My tolerance for people who flinch from screen violence, and insist that they have no time for violent movies, is accordingly extremely low. It seems to me nothing other than moral squeamishness … Yet this weakness is, to all intents and purposes, presented to us as virtue.” That may not seem very tolerant of the people who simply can’t watch screen violence. But would we accord them the same sympathy if that squeamishness were used as an excuse to avoid “The Painted Bird” or “Macbeth” (or Goya or “Guernica”)?

Horsley is not arguing for a blanket acceptance of any screen violence. There are certain depictions from which even he flinches. “We don’t need a film to show us that violence is sordid and repulsive,” Horsley writes. “We already know this.” So what is the purpose of a violent film? On the surface, Horsley’s answer seems depressingly familiar. “If movies can serve to bring us closer to understanding our feelings about violence,” he writes, “our fear and our fascination and our loathing of it, then they have served a useful, essential purpose, a social function no less, and deserve to be tolerated, as does all art, no matter how shocking or ‘immoral’ they may ostensibly be.”

Horsley isn’t wrong; it’s just that a better answer emerges in his individual readings of films. Horsley hits on the essence of what constitutes an effective depiction of violence when he says, “Clearly it is not a matter of realism.” Realism is often confused with plausibility, or emotional and psychological coherence. Movies, though, are not real. So when movies set out to give us stark, documentary depictions of violence, they have abandoned the mediating essence of art. That’s why Horsley finds “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer” unwatchable and why his defense of “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” rings false. Describing a scene of a woman hanging on a meat hook as her boyfriend is dismembered before her eyes, he writes, “We get a genuine sense here of just what must be going through the character’s mind in her last moments — of the absolute horror of being so abruptly and ruthlessly dragged from her pleasant everyday oblivion into this world or madness, pain, and dismemberment.”

I don’t doubt that the movie does justice to the level of violent senselessness that Horsley describes. (I’ve never had the guts to see it.) What’s missing from that description is a sense that the film provides anything beyond the character’s misery, which can never be the sole point of violence. Artful movie violence needs to express or contain some sort of larger emotional or visceral quality. That’s the extra dimension that separates abject suffering from transcendence. That’s why torture scenes (and most rapes) are nearly always a mistake. It’s why I can’t abide movies in which harm comes to animals (nearly always a cheap device); there’s something obscene about inflicting pain on a creature that has no understanding why or even that it’s coming.

Implicit in the richness of Horsley’s response to the movies he discusses is that even the most intense art, if it is to be art, has to function at some sort of distance. I don’t mean that we should watch movies from a safe, detached vista. Again and again Horsley makes the point that great violent movies (great art of any kind) should stir up uncomfortable responses. It’s not a lulling experience to find yourself thrilling to the last-stand suicide that climaxes “The Wild Bunch” — or, an even more extreme example, understanding the orgasmic release when Travis Bickle explodes in “Taxi Driver” or the combination of self-loathing and sexual triumph when Kyle MacLachlan gives in to Isabella Rossellini’s demands in “Blue Velvet” and hits her as they’re making love.

We’re able to access the conflicted emotions of those moments precisely because they have come to us via the vision of an artist. Movies may be a special case because their bigness and immediacy make them the most visceral of the arts, the hardest to defend yourself against. The same is true in literature, though. Compare some of the most horrific violence in fiction — the murders in “Crime and Punishment,” in “Native Son” or in Norman Mailer’s “An American Dream,” scenes that put you through the long, grueling process of what it means to kill someone — with the cold and repugnant designer-tabloid mutilations of Bret Easton Ellis’ novel “American Psycho.” It’s not just that the book’s coldness fails to render the extremity of Patrick Bateman’s emotional state — it’s that it contains no emotions. That’s the point; Ellis has rigorously excised both horror and pity from his simplistic sociological swipe at the yuppie-eat-yuppie ’80s.

Even at its most upsetting, the best movie violence has a touch of poetry, perhaps horrible poetry, but poetry nonetheless. There is such a thing as going too far, but that often has less to do with what happens or how much we see than with the respect that the artist accords the audience. The unconscionably prolonged climax of Lars von Trier’s “Dancer in the Dark” is the closest thing I have ever felt to being emotionally raped by a movie. The fate of Björk’s character is less the result of a conscious choice on her part than a moment of desperation. Her fate is wildly out of sync with what she’s done. Clearly, that’s part of von Trier’s point. But to linger on that fate as long as the director does is a violation of his heroine as well as of the audience. It’s just squalid and horrible, not tragic or resonant. There’s no difference between an “art” film that pushes the limits of pain, violence and suffering and an exploitation film that grooves on the same excess. They are both trying to shock the audience by going “too far.”

“The Blood Poets” is the first work of criticism to talk at any length about how the exploitation impulse has crossed over into the work of respected filmmakers. In his section on “The Silence of the Lambs” (particularly on the film’s glamorization of Hannibal Lecter) Horsley nails the intellectualized disgust that marks such betrayals of talent as David Lynch’s “Wild at Heart” and especially Martin Scorsese’s “Cape Fear.” (He might have said the same of “Se7en” if he hadn’t been snookered by its wages-of-sin hoo-ha.) What he writes of “The Silence of the Lambs” could suffice for any of these films. To Horsley, these movies represent an indication that “the audience is so utterly, cynically bored and disgusted with their lives (and with society as a whole) that they can take a perverse, almost suicidal pleasure in seeing it all come apart before them. A depraved maniac wandering free as a bird, enacting his sick revenge upon a society which he holds only in the utmost contempt, as beneath him, this idea meets with the approval, if not plain delight of the modern audience.”

That’s a brand of complacency, of superiority to the victim, that is unthinkable in any of the great American violent films. It’s an attitude that really only has an equal in splatter movies where the audience waits gleefully — not in trepidation — for each new killing. In the view of the audiences ready to celebrate the triumph of chaos, the vindication of the belief that it’s all crap, we are all asking for it. We are not implicated in either the commission or the impact of the violence the same way we are in the best work of Scorsese or De Palma or Peckinpah or Coppola.

Do violent movies lead audiences to accept violence complacently, to become desensitized? Yes, I think, unquestionably. But it’s always the idiot masses who are presumed to be alone among the desensitized; the “discerning” audiences who whoop it up at the bumbling terror of the whimpering kidnap victim with the bag over her head in “Fargo” — or those who simply forget the horror of her fate when dubbing the movie “warm” — or the critics who invent elaborate justifications for a piece of sadoporn like “Se7en” never get the finger pointed at them.

Lest this sound like a brief for the poor, misunderstood masses, I should add that I don’t feel much better about the moviegoers who have learned to treat every violent movie as if it were just a kick. Some years ago at a college showing of “Bonnie & Clyde,” I wound up sitting with a girl I knew from some of my classes. In our few talks, we had discovered we both liked the same movies. Despite the fact that we had both seen “Bonnie & Clyde” about 10 times between us, we found ourselves, in the moments before the violence exploded, squeezing each other’s hands, neither of us moving our eyes from the screen. The guys behind us were another story. They kept making little shotgun noises and waiting gleefully for the blood to start splattering. They were as anxious for the violence as my friend and I were dreading it.

Who do you blame for that sort of bonehead insensitivity? Surely not the film’s director, Arthur Penn. Making the film’s violence voluptuous is hardly the same thing as offering it up for our delectation. It goes without saying that moviegoers eager to drag everything down to the action movie level have no frame of reference to respond to great nonviolent movies. If you were to put them down in front of, say, “The Best Years of Our Lives” (let alone “Rules of the Game”), they’d think there was nothing going on. So they often have no frame of reference to respond to great violent movies as if they were anything more than a cheap thrill.

Still, there’s no getting around the fact that what we enjoy in action movies and thrillers and horror movies is often the violence. Bloody violence can be a real turn-on. When a stream of blood squirts back in the ghostly, flour-whitened face of Chow Yun Fat as he dispatches a bad guy in “Hard Boiled,” the moment has the satisfaction of a perfectly timed punch line. Movie violence can be funny, the capper to a great sick joke, and not just in action movies. Think of the shocking moment in “Ran” when Akira Kurosawa denotes the murder of the duplicitous Lady Kaede (Mieko Harada) by a jet of blood hitting a screen. The swiftness of the action, the unexpectedness of it, and the fitting justice make you gasp and laugh. Of course, you wouldn’t be able to laugh if both these victims didn’t have it coming. The filmmakers are making an implicit pact with the audience that the deaths of the innocent won’t be treated in the same way.

There is a level of deadness and insensitivity (moral as well as aesthetic) in contemporary movies that can make the solutions of the panicmongers who want to regulate all violent media seem eminently reasonable. It’s appalling to hear stories like the one that came out a few years ago about California school kids hooting and hollering on a field trip to see “Schindler’s List.” The e-mail I got from alarmed kids asking me whether “The Blair Witch Project” was a true story bothered me because it suggested that we’re living in a culture where the notion that real terror and distress could be presented as if they were just a scary entertainment isn’t out of the question. The harm of bad violent movies isn’t that somebody will confuse them with reality and take them as a brief to go out and commit real violence (though, because there are unbalanced people in the world, that possibility exists with good movies as well as bad). The real harm is that they do exactly the opposite of what good art should do: deadening us instead of making us more alert and alive and responsive.

Bad art in general is desensitizing, even the kind that seems to sensitize audiences by reducing them to blubber. I think someone who weeps at “Terms of Endearment” or “Titanic” has been desensitized to death and suffering. A movie that presents a tidied-up version of cancer as though it were the real thing, or reduces a historical tragedy to a special-effects show, is far more repugnant to me than a movie that sells the sort of fantasy where one lone hero slaughters a cadre of bad guys. But people who cry at “Titanic” don’t stir our fears the way a kid who hollers “Awrrright!” at some act of brutality does.

I’ve shared that fear. For every action movie in which I’ve enjoyed watching bad guys get blown away (like this year’s remake of “Shaft”), there have been three of four where just sitting in the theater made me feel as though I were taking part in some sordid ritual. And though I’ve sometimes felt cut off from moviegoers weeping over some manipulative drivel, I’ve never felt repulsed by their tears the way I have by some of the cheers at the cheesy violent movies I’ve sat through. I’ve been a professional film critic for 15 years and it becomes easier and easier for me to slough off the mindless, emotionless violence of genre movies. But the older I get the more bothered I am by the violence that just makes me miserable or nauseous without giving me anything in return.

Horsley calls movies “the most sensationalist art form in history” and he makes a damn convincing case that violence is at the heart of that sensation. The enormous advances in special effects that have come about through computer graphics and other processes allow movies to play with all sorts of sensations that would have been unthinkable — in all ways — just a few years ago. When those tools are put in the hands of real filmmakers, the result can be as imaginative and as playful as “The Matrix.” But the same devices are also available to hacks who will use them to bash us into submission without a second thought. Just as the kids born after “Star Wars” grew up taking for granted the level of special effects that film ushered in, the generation just now discovering movies will eventually take for granted this new bag of technical tricks. And filmmakers will keep upping the doses of sensation to wow audiences with things they’ve never seen before. There’s no getting around the inevitability that movies just a few years down the road will hold new flights of imagination — and new strains of brutality — that we can’t even imagine yet.

Bad, brutal, insensitive movies will always be with us. And good movies will somehow still manage to get made. There will be dozens of repulsive movies, and some few that will find ways to make violence fresh instead of routine, that disturb us rather than disgust us. Within the last year, we’ve had both the stupid, reactionary “The Patriot,” cloaking itself in American history while debasing it to the point where audiences cheer as the American flag is turned into an instrument of murder, and the stunning, innovative “Three Kings,” which treats a slice of recent history as bloody, political vaudeville. Both movies are soaked in blood, and both feature people put to horrendous deaths while their families watch. But where “The Patriot” stokes the fires of revenge, “Three Kings” early on brings the mercenary heroes to a point where they are appalled by the killing around them. That “Three Kings” manages that without ever sacrificing excitement or its appeal as an action-adventure is as true an example as any of how violence can turn us on viscerally, emotionally and morally all at once without providing any easy answers.

“The poet,” Horsley writes, “is the pioneer of consciousness … As such, he is all but compelled … to resort to the most ruthless, cunning and violent of tactics. What redeems and transforms this ruthlessness is his ability to put brutality at the service of beauty, and to make poetry out of the slaughter.” The key word there is “beauty,” which in the movies can mean the moonlit fields of F.W. Murnau’s “Sunrise” with their nimbi of light, or the delicately lit period interiors of Terence Davies’ upcoming film of Edith Wharton’s “The House of Mirth.” And it can just as easily mean the dead, blue face of Laura Palmer in “Twin Peaks,” at peace at last in the big sleep, or Bonnie and Clyde straining toward each other as bullets cut their bodies to pieces.