Money equals power. That truism is becoming truer every day in Washington -- and is what's driving the renewed push for campaign finance reform. And if you go 3,000 miles west, you'll see just how true it has become.

There are many angles to the California energy crisis, but the one with the most urgent national implications -- now that the president and Sen. John McCain have met for a "friendly" chat about the McCain-Feingold campaign finance bill -- is the role campaign contributions play in determining policy and in blinding politicians to the consequences. With Big Power's donations filling their coffers, California's leaders have been suffering even more rolling blackouts than its citizens.

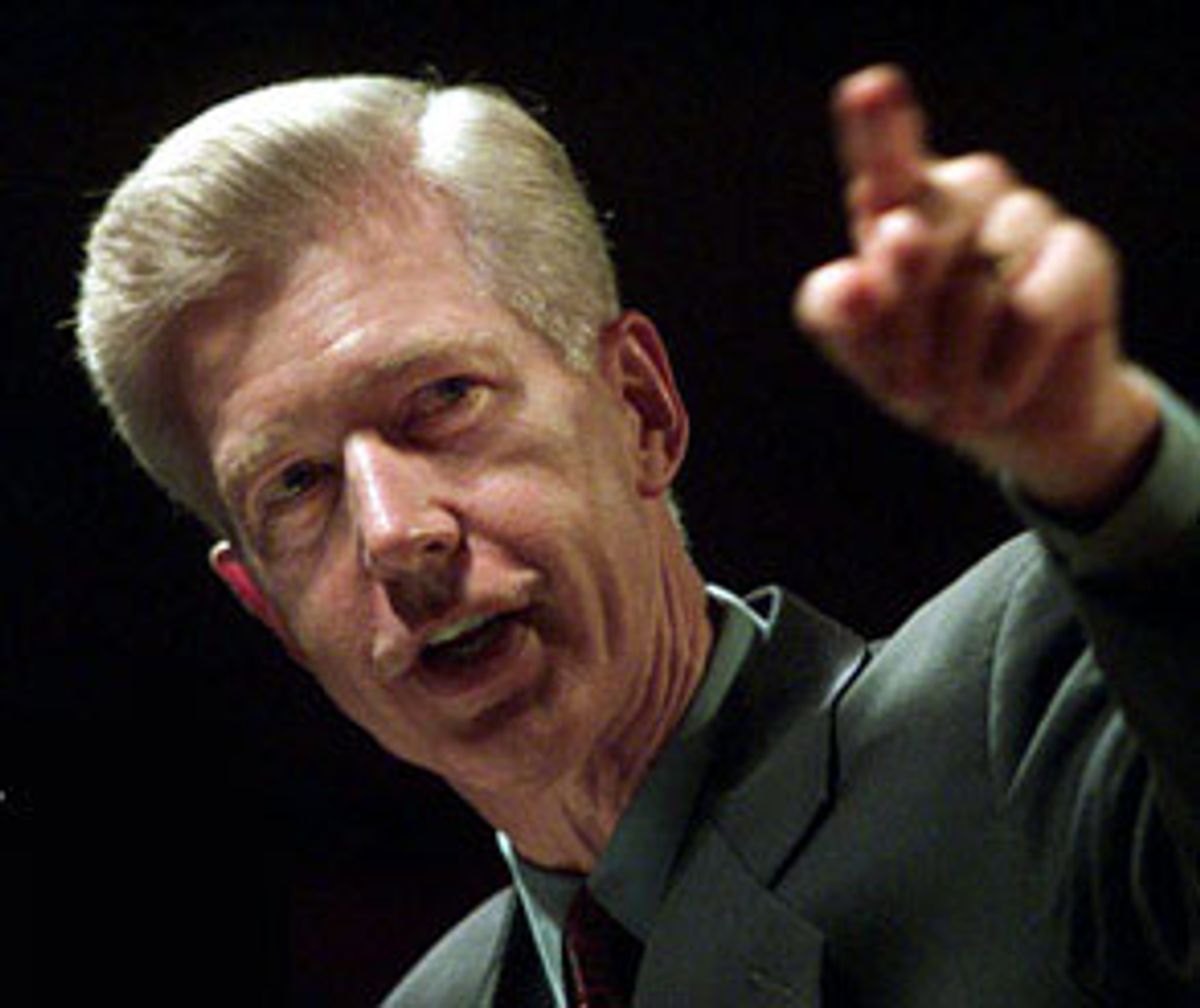

Gov. Gray Davis, a middle-of-the-roader whose grand political vision begins and ends with the desire to offend no one -- especially anyone with a checkbook -- was found asleep at the wheel while his state careened toward an energy disaster. The interesting question is: What made him so drowsy?

Could it be the steady IV drip of soporific campaign cash he received from the two giant utility companies at the center of the current crisis? According to state records, since 1998 Davis has taken in $550,000 from Southern California Edison and Pacific Gas & Electric -- his share of the $7 million the companies have doled out to politicians from both parties during that time. One of them, state Sen. Steve Peace, hailed as the "architect of electricity deregulation," received $179,409 between 1994 and 1998. If only the utilities were as good at buying electrical power as they are at buying political power.

Of course, as is de rigueur in political circles, the governor has issued the standard, boilerplate denials that the money influenced his decisions. "It doesn't affect him one way or another," said Steve Maviglio, Davis' spokesman. "There is no connection between contributions and policy."

This has become one of those lies -- like "We'll be pulling away from the gate momentarily" -- that we hear so often we don't hear it at all. If it were true, then why did the Davis camp tout to the press that the governor has not taken any money since October from the companies he's being asked to bail out? As though abstaining from orgies of campaign cash for a few months can restore one's political virginity.

Indeed, the governor's office proudly announced that Davis had turned down an offer by a group of independent energy producers to hold a fundraiser for him last month. Putting aside the ludicrousness of painting the rejection of a fundraising opportunity as an act of great strength and moral leadership, why would Davis stop accepting utility company contributions if, as he claims, there's "no connection between contributions and policy"? And if he wants credit for turning the money down when the lights -- at least the media ones -- are on, why won't he accept the implications of taking the money when they were off?

And what are we to make of the governor's decision to avoid meeting with the utilities' top executives prior to their recent negotiations because, according to his spokesman, "he wanted to stay away from the fray and not be influenced"? So Davis can be influenced by meeting with people, but not by pocketing their money?

In the same spirit of pretending that campaign contributions really don't matter, the utility companies decided last month to hold off on making any more donations. "We didn't want it to be misunderstood," explained PG&E vice president Frank Regan.

Yeah, you know how confused taxpayers can get when they're being asked to fund a multibillion-dollar bailout of two companies that, between them, made more than $6 billion in profits since deregulation began and have combined assets of approximately $71 billion. Don't you worry, Mr. Regan -- we understand perfectly.

For those of us following the money, an interesting story line we'll be watching is whether there will be even a sliver of daylight between the wishes of Bush-backer extraordinaire Kenneth Lay, chairman of energy giant Enron, and the Bush administration's energy policy. Lay -- who was the single biggest contributor to Bush's presidential run with more than half a million dollars in campaign donations and an additional $100,000 for the inaugural festivities -- would love nothing better than to see the state bail out California's struggling utilities, thereby ensuring his company is paid the huge sums it is owed.

Not surprisingly, this week Bush shifted from his previous zero-federal-intervention stance and extended until Feb. 7 orders forcing California's neighbors to deplete their own energy resources to keep the lights on in the Golden State. I guess this is a case of donor rights trumping state rights.

For his part, Lay, who is also a key member of the advisory panel Bush formed to help shape energy policy, has proved exceptionally adept at playing the political money game. Why else would a close friend of Bush's, and ardent supporter of the Republican agenda, have his company donate $93,000 to Gray Davis?

The crisis in California is an object lesson in the corrupting, and disorienting, influence of money on our political leaders. Let's hope those opposing campaign finance reform back in Washington take it to heart -- before the lights go out on our democracy.

Shares