Agnès Varda's "The Gleaners and I" is something of an odd bird, a cross between a documentary, an art film and a personal reflection on aging. But just in case any of those things, let alone a combination of the three, is enough to make you head for the hills, it's important to stress the solid, workaday qualities that keep "The Gleaners and I" from floating off into the ether. To the extent that it qualifies as an art film, it's one that's also urgent, graceful, accessible and at times openly cheerful -- it takes a big bite out of life.

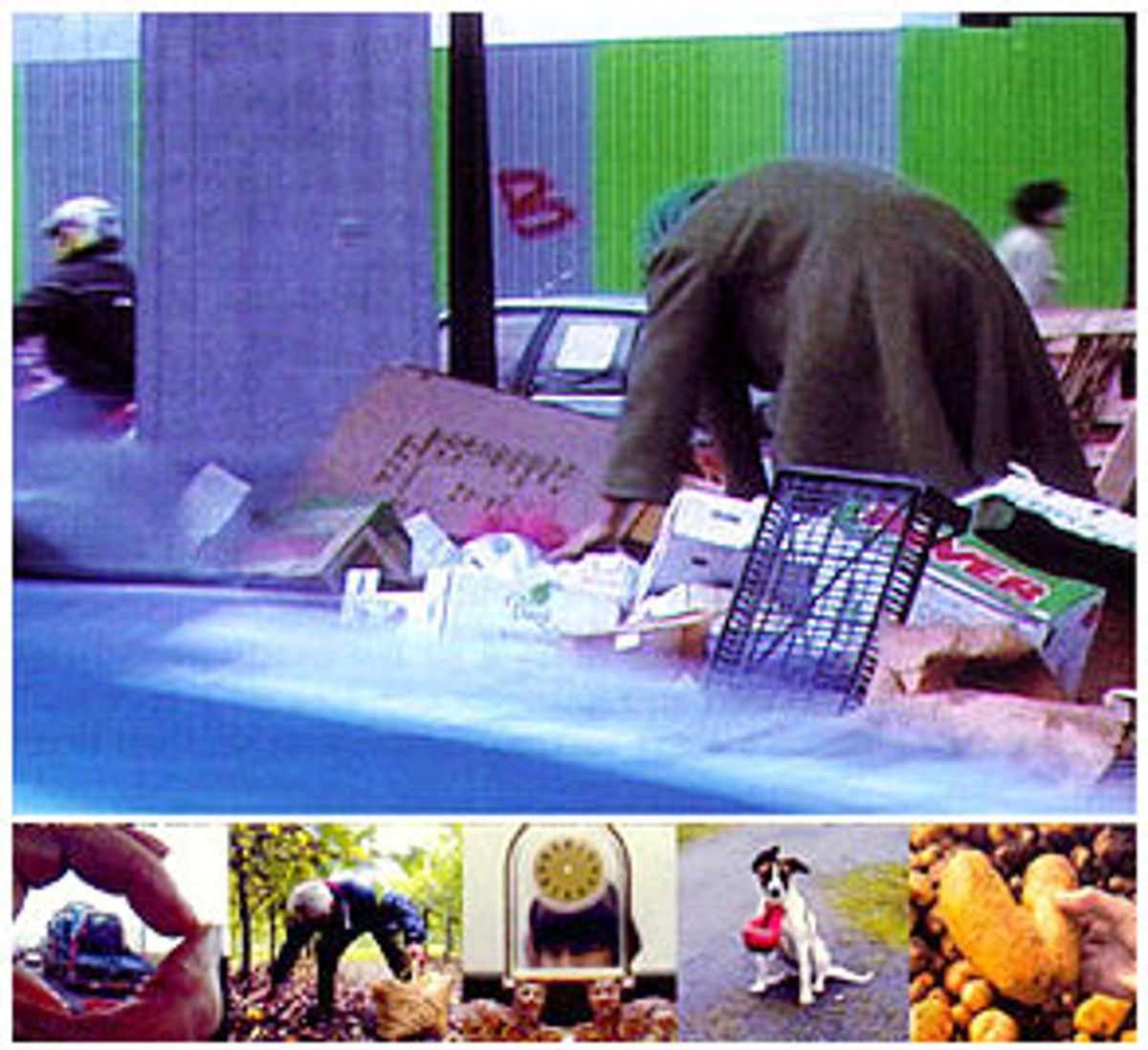

Varda, the director of pictures like "Vagabond" (1985) and the clear-eyed, nerve-buzzingly touching "Cleo From 5 to 7" (1961), has been a denizen of the French filmmaking scene since the late '50s. Early shorts like "L'Opéra-Mouffe" (1958), which glories in the sights and sounds of a neighborhood market from the point of view of a pregnant woman, suggest that she might be the missing link between surrealists like Jean Cocteau and new wave visionaries like Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut. In "The Gleaners and I," she follows a ragtag selection of gleaners as they go about their usual routine. Gleaners are defined here as people who pick up usable food or goods that others have no use for, whether that means salvaging rejected fruits and vegetables after the harvest or scavenging discarded furniture curbside.

Varda's inspiration for the movie, as she explains in the narration, was an 1857 painting by Jean-François Millet showing women in a wheat field, stooping to pick up the remnants of the harvest. The painting, a large but modest picture rendered in glowing golden browns, is the touchstone for the film, and it's oddly galvanizing: The action in the painting (embodied wholly in the curved forms of the women laborers), as in the movie, is gentle but never static. Both Varda and Millet show a smoldering desire for constant motion, a delight in moving forward, but never so quickly that a telling detail -- whether it's a charmingly heart-shaped potato or a stray shaft of wheat -- might be missed. As lovely as it is to start something new, there's also plenty of beauty in bringing an endeavor to a natural and complete closure.

Varda's filmed essay combines her own voice-over narration with images drawn from Paris and the French countryside. (The movie was shot on digital video, but unlike so many DV pictures, it looks casually steeped in richness instead of washed out.) She speaks with gleaners who show up in a potato field, post-harvest, to pick up the knobby misfits left behind by the farmers, most of which are still perfectly edible -- just not pretty and choice enough to bring to market. She talks with gleaners who forage out of necessity (like the gangly, balding, alcoholic Frenchman who looks as if he's carrying the sorrows of both hemispheres in the bags under his eyes) and those who do it almost out of a sense of social justice, people who are grounded in the sturdy conviction that good food should never be wasted (like the cheerful chef of a highly rated restaurant who's adamant about picking, not buying, his own herbs).

She follows an artist who scours the streets on trash day for found treasures to incorporate into his art, and an articulate and well-educated gentleman who strolls the streets after the open-air markets have closed, seeking discarded fruits and loaves of bread that spill out of busted crates and torn bags like pirates' treasure.

Varda isn't just an observer, a voyeur with a lens. She takes great pleasure in joining the dance, at one point pulling fat, juicy, overripe figs off a tree and tearing into them with her teeth as she grumbles about landowners who won't allow gleaning. ("They won't allow gleaning because they don't feel like being nice," she growls.) And in the movie's most pleasurably goofy moment, she films the lens cap of her camera dangling lackadaisically against a background of brush and leaves, an accident (it seems she was just walking along and simply forgot to turn off her digital camera) that she turns into a stylish fillip by adding a minute's worth of jazzy alto-sax toodling.

The movie's central metaphor is clear from the start, and Varda even states it herself early on: Filmmaking, particularly the pieced-patchwork sort that Varda does here, is its own kind of gleaning, a way of picking and choosing images that others might not give a second thought to. But Varda is as interested in the very ground we tread as she is in airy ideas. It's true that Varda's picture trades in metaphors and symbols at least part of the time. When the director films her own hand, encircled around the sight of a giant tractor-trailer truck zooming down the highway, she's really just looking at the world through an aperture of flesh, muscle and bone, a symbol of the way movie images can become ingrained in us, and have become ingrained in her. But much of the time, "The Gleaners and I" is strikingly straightforward and muscular, digging into potentially nebulous issues like the impermanence of life with the same earthiness that it uses to document the lives of people who live close to the edge, living day by day on very little means. With her camera, Varda finds the gracefully melon-shaped center of a Venn diagram where lyricism meets common sense.

Even though it's intensely, if sometimes offhandedly, personal, there's nothing precious or aggressively self-absorbed about "The Gleaners and I." Varda is in her early '70s. While her sense of mortality isn't the overarching theme of "The Gleaners and I," it does shoot through the movie like a silvery thread, surfacing here and there before Varda clips it short, almost impatient with herself for even bringing it up. Early in the movie, she briefly trains her lens on the crinkled landscape of her own hand, saying simply, "My hands keep telling me that the end is near," before she jumps abruptly, assuredly, to the more crucial business at hand, which is the showing of her newfound gleaner friends at work.

Later, cruising the streets on garbage night with an expert-trash-picker friend, she picks up a transparent Plexiglas clock face with no inner workings and no hands. Then she shows us the clock sitting squarely in the center of her mantel at home, flanked by two smiling china cats. "A clock without hands is my kind of thing," she says, jauntily, in voice-over.

Who wants to be reminded of the passing of time, but more important, who needs it? "The Gleaners and I" isn't a scolding treatise about the shamefulness of waste, but a celebratory jig inspired by the pleasures of squeezing every last, sweet drop from a grape harvest, or giving a tossed-off bit of plastic tubing new life in a 3-D painting. At the same time, Varda tints every frame of "The Gleaners and I" with a kind of joyous mournfulness: When you realize life is slipping by you, you want to hold on to every scrap.

Shares