I imagine my son swaying at the counter, shifting from one foot to the other. He says "Huh?" when the cashier tells him how much the boombox comes to with tax and when she tells him again, he stares at her. Then he pulls a credit card from his wallet, rattles it on the counter, spins it between his thumb and forefinger, and puts it away again. He asks the cashier if this boombox is the most popular model. He asks her if she thinks he should use his credit card or his checkbook and she frowns slightly, not just at the questions but at the timbre of his voice, which sounds as if it comes from some node of tissue not typically used for sound.

Maybe she figures it out. Maybe she realizes that this young man is special in a way not implied by the sign over the cash register proclaiming: "All our customers are special." Maybe she relaxes a bit; maybe she even enjoys suspending her routine to watch my son as he prints the store's name on the check in letters like sticks thrown on the sidewalk, as he pauses to ask her how to spell "forty." Or not; she might exchange annoyed looks with the other not-as-special customers who are piling up behind him with their boxes of computer peripherals and televisions. She might even grin when one of them brays his impatience.

How much of this does my son notice on this day of firsts -- his first time taking the five-mile bus ride to this store from his new apartment, his first time making such a large purchase on his own? I'm not there but my guess is, not much. My guess is that he's thinking of the burly electronics inside the box, of the spot he's cleared for the boombox on his dresser between the Special Olympics medals and the bowling trophy. He's thinking of the well-ordered plentitude of his music; he's deciding which tape or CD he will play first and he knows exactly where it rests, in which case, in which Plexiglas slot. He doesn't notice the stares and grumbles, and they won't change the way he makes his way through this checkout line the next time he visits this store. These are details nearly as arcane to him as the rules of punctuation or boccie ball.

This kind of oblivion has been both a curse and a blessing during his 25 years. On this day, it would be a blessing. Matthew leaves the store's mutterers behind. He grips his boombox under one arm, and he tromps to the bus stop as his other arm pistons into a January fog. After he finds his seat on the bus, after he settles his package on his knees, he raises his fists and shakes them around his face like maracas. This is how he expresses joy.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

I was a little girl with apocalyptic visions. I was also very practical; every night, during my last moments of clarity before sleep, I worked out strategies to avert disaster. Worried that people were frittering away the world's supply of fresh water, I imagined household systems that caught lightly used water and piped it into gardens. Mindful of the burgeoning pile of human waste, I imagined adding a mystery ingredient to ordinary poop and turning it into something useful like bricks or asphalt. And then there was overpopulation: I imagined peeling away all the layers of humanity that made life harder or less pleasant. I made whole categories of human beings vanish: the bad people who were in prison, the crazy people who shouted from street corners, the retarded people who didn't really do any harm but weren't able to contribute much, either. Before I fell asleep, I always amended this last final solution: My older cousin Stephen could stay in my emptier, ideal world. He was retarded, but he was always very sweet to me.

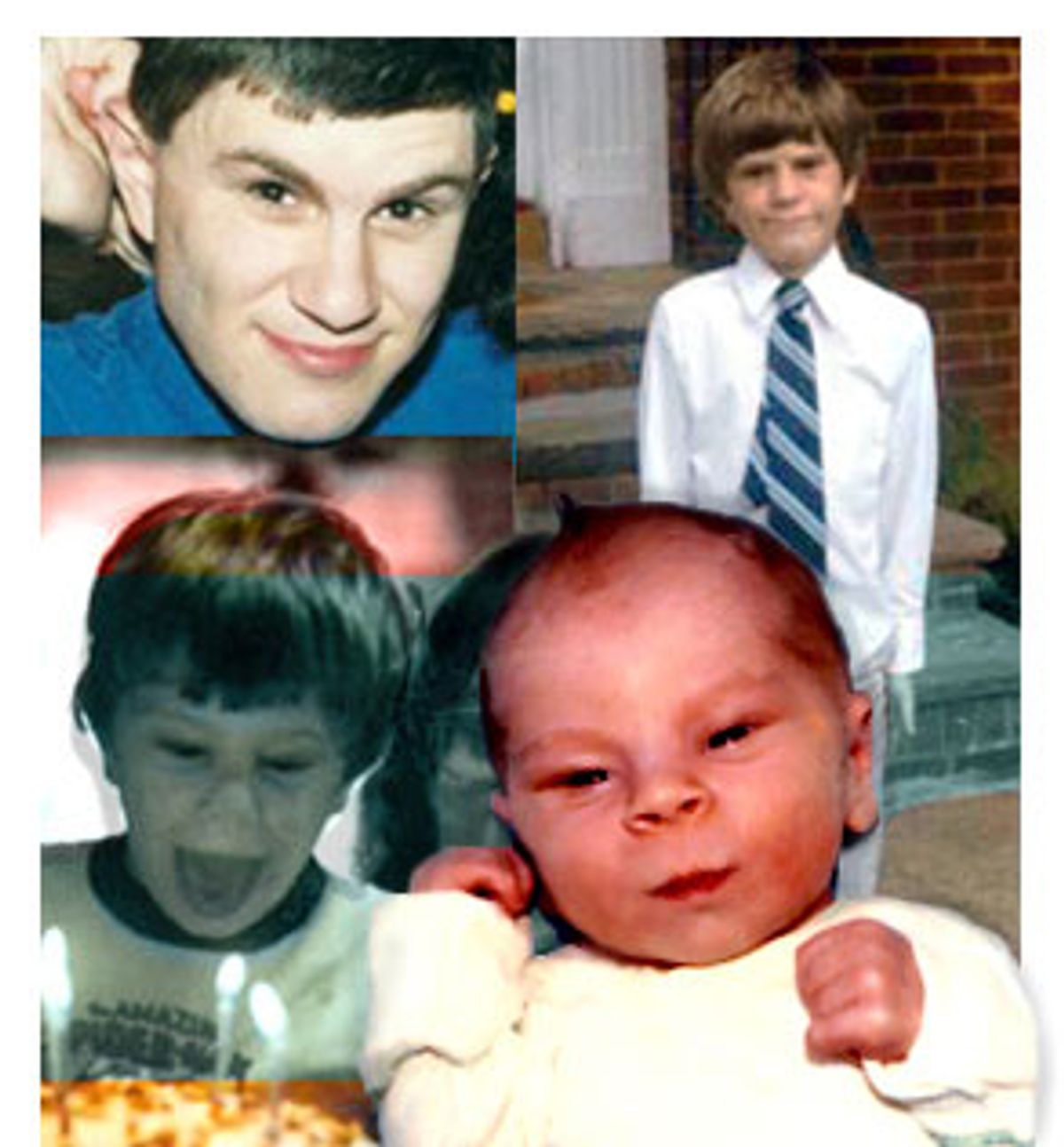

My Matthew, my first child, was born nearly 20 years later in a hulking old Cleveland hospital. The pregnancy was lovely until the final, ponderous weeks, and the delivery was unremarkable until Matt slid into the doctor's hands. Then, from way up at the head of the bed, I heard all the voices in the room assume a quiet, measured urgency, as if they were creating a blockade of words to keep something quick and terrible from being said. They didn't bring him to me, at first. Then someone came to tell me he had been born with the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck and that my amniotic fluid had been stained with his excrement. I'm sure I asked if he was all right and I'm sure they told me something, but it wasn't until days later, after he spent his first days in an isolette and had been observed and tested, that they told me he was fine.

I don't know that I ever believed them. Although I never saw Matt lined up with all the other newborns in the hospital nursery, he seemed different from the other babies I knew. He was pale, his eyes were puffy and bruised looking, and his waking moments were filled with noise -- not the howling his father and I had braced ourselves for, but chirps and grunts and twitters. He generated his own white noise. When I'd tell other people about this, they'd sometimes pat my arm indulgently and tell me each baby had its own enigmatic little personality. Give yourself time to get to know him, they said.

I tried to get to know him, but he seemed uninterested in either his father or me. When I'd pick him up he'd startle, his arms jerking like small featherless wings, and he never seemed comforted by my touch. When I'd talk or sing to him, he often didn't even turn his head; if he did, he soon turned away without interest. Instead of looking at me, he'd stare at the light bulb or the glare coming in a window or, as he asserted more control over his limbs, the restless movement of his own tiny fingers. We could get him to smile or laugh, but with great effort, usually after his father had thrown him in the air over and over again. It seemed to be the movement, not his parents' adoration, that pleased him.

It seemed that my fears about Matt would be confirmed if I spoke them out loud, so I didn't. Still, I felt like the unnamed differences that set him apart from all those other babies lurked around corners; I felt that if I left him unguarded, these differences would snatch him away for good. The playpen that well-meaning relatives gave us held unfolded laundry in the corner of the living room. Instead of using it, I would hold Matt often and carry on a hopeful monologue. I would set him down on the floor and crawl around him in circles, trying to make contact with his disinterested gaze. When Matt woke up at night crying, I would pick him up but he'd cry even harder and push away. I'd put him back in the crib to comfort him, then sit on the floor weeping as he flailed himself back to sleep.

When he was 8 months old, I took him to the pediatrician for a routine checkup. My mother-in-law from New York came too. We were in high spirits: We had big plans to go antiquing in Amish country after the doctor's appointment. But instead of the usual pleasant chitchat about appetite and bowel movements, the doctor studied Matt's face and called his name from different parts of the room. He snapped his fingers near Matt's ear, then watched him startle, look up and turn away. He wiggled a toy over Matt's head and made a fake, falsetto laugh, then sighed as Matt frowned in the other direction. I was afraid that the doctor was searching for something I didn't really want him to find.

"He should be more interested in people," the doctor said, looking sad. "He should be looking around for Mama or laughing with me at the toy. Instead, he looks at the shiny handle on the cupboard."

My mother-in-law was able to ask all the important questions. I couldn't speak or even follow what she and the doctor were saying. I picked Matt up and rubbed my face against his hair, wishing he would nestle against me just this once.

We didn't go antiquing, of course. We went home and made phone calls to the neurologist the pediatrician had recommended. Then we made the harder calls, the ones to my parents in California and to our friends and to all the others who loved this baby and his parents from afar. My mother-in-law stayed for many days, and then my parents took a shift, and then my mother-in-law came back for a while longer. I stayed in bed with the curtains drawn as much as I could, thinking sometimes of the girl who had gone to sleep with Hitlerian schemes for a perfect world. By the time Matt was born, I didn't believe in God, luck or fate. Still, I had some kind of certainty that those long-ago thoughts had ruined my baby boy.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

My mother-in-law tells me that I said something very wise during that first year. At some point in the ongoing conversation about syndromes and specialists and our wrenching shift in expectations, I lifted my head and looked at my son. I said, "We have to have faith in the baby."

I don't remember saying this, and I don't know that the next few years showed great faith. We worked with a neurologist, we found a wonderful pediatrician who specialized in children with problems, we went through a slew of speech therapists and music therapists and psychologists and the like. We took Matt to oddball practitioners, too -- a hypnotherapist in Minneapolis, a listening therapist on Cleveland's East Side, a pediatrician on Cleveland's West Side who immersed a lock of Matt's hair in solution to look for chemical irregularities. Matt was tested and observed over and over; today's healthcare system would never allow such vast duplication of effort.

In the end, there was no culprit to pursue -- no smoking gun among his chromosomes, no malfunctioning organ, no negligence or error by the hospital during delivery. There was only a description. He was retarded -- significantly so, in the early years -- with what they called autistic-like behavior.

It seemed like a betrayal when we stopped looking for cures and began to accept our child as he was. Matt reached most of the developmental and social milestones, albeit later and with greater fanfare than most babies. He walked when he was 1 and a half. He said his first word after he turned 2. At 3, Matt succeeded in using his potty chair, with me, his father and my in-laws watching. We cheered so much that Matt's great-grandmother abandoned "Perry Mason" and came running; she thought we had won the lottery.

When Matt was about 4, we were walking down the street and, all of a sudden, he was not beside me. I turned around to see him saying something to an old man who was sitting on a blanket by the side of a building. "Friendly kid," the man said, waggling his fingers at me. "He came right over and started a conversation." This was a milestone as important as the others: Without prompting, without anyone calling his name or waving a toy, Matt had approached another human being.

We had our second baby, Jamie Rose, when Matt was nearly 3. That initial year was lovely but sad because it forced us to relive all we had missed with Matt. When Jamie grinned as I ran my finger over her lips that first week, when she began to watch intently as I walked from the sink to the table to the stove, when she cried as I left the room, I mourned again the gulf that had separated me from baby Matt.

When I took the two of them out, the comparison was even more painful. Jamie's lashes grew in long and black, her hair glowed in golden ringlets, her eyes shone an opal blue, and she soon learned to enjoy the attention of people in grocery stores. They'd let the ice cream melt in their carts as they cooed over her. The same people looked at her brother uneasily, not sure what to say to this child who flinched from their gaze and whirled in ceaseless activity at the end of my arm.

He grew, they grew, we all grew. Matt and Jamie were pals during their early years. She came along to all of Matt's therapeutic play groups and classes, tumbling in with the other "special" children as well as their siblings. In addition to these activities, I dragged the two of them through the full array of middle-class enrichment. I enrolled them in classes at the art museum, the natural history museum and a dance studio; they took ice-skating lessons and joined Pee Wee soccer. I stayed through each of these activities, ready to herd Matt back into the group if he ran off, wincing every time one of the other children would stop to stare at him shaking his hands around his eyes. Still, I persevered: I had a foolish hope that one of these activities might tap a hidden source of brilliance in him, make neurons dance the way they had when Mozart first heard music or Einstein saw stars. People were fond of suggesting these duckling-into-swan analogies to me.

When he was 7 years old, Matt was placed in a public school class for multihandicapped children, a cozy nest of eight such mysterious ducklings with a teacher and two aides. A bus pulled up in front of our house every morning driven by a cheerful man who sang "Volare" along the route, and Matt rolled away from me without a backward glance. I visited his class often. The teacher was droll and matter-of-fact about her assortment of quirky characters; she was fond of dismissing their quirks as an overdose of their parent's tendencies. "Look at him," she'd say, as Matt raced from one activity to another. "He's just like his father!" Enough time had passed since the shock of Matt's diagnosis that I found this funny.

I met other parents who were also at this stop on the road from grief to acceptance -- confronted by the things in our children that we couldn't understand or change, it helped to laugh. I remember going to a festival once with Vincent, a boy in Matt's class, and his mother, Carol. She and I walked together, the boys walked in front of us and we could hear their animated nonconversation. Vincent was talking about baseball, Matt was talking about cartoon characters and neither listened to the other. Carol said that she imagined that in some mirror-opposite universe, two boys were also leaving a festival with their mothers. "Those boys are saying, 'Mothers, might we stop for a snack?'" Carol pantomimed the boys' exaggerated courtesy. "And one mother answers by repeating the score of yesterday's game 10 times and the other answers with 'Go, go Gadget!'" It was an apt way of describing how estranged we sometimes felt from our children, how cosmically and comically mismatched.

Matt stayed in the multihandicapped class for three years. Toward the end of the third year, the psychologist we'd been taking him to ever since he was a toddler administered a routine I.Q. test. The next time we saw her, she rushed into her office with a bulging file of papers and a look of great excitement. "I have wonderful news," she announced. "Matt is not retarded!"

In a way, this was meaningless: Matt was the same person he had been the day before, but his unanticipated ability to match like objects in one part of the test had pushed him over the threshold to the bottom tier of normal. "That's great," I told her, but more to be polite than out of any real feeling. Even though there had been a time when I would have cherished this new, improved labeling, I knew by then that my son was a complicated being who defied categorization, that even though a new hole was being offered he would still be the wrong shape for it. And I can't say that what followed was good for him, although it's still hard to tell. He was now ineligible for the multihandicapped class. The option suggested by our school system was to put him in a regular classroom in our neighborhood school with pull-out hours in the learning disabilities resource room. In other words, he was mainstreamed.

Mainstreaming isn't so bad if you're part of the mainstream. The next four years of public school were difficult, and I take little solace in the possibility that all those other kids got a lesson in compassion by being around Matt. It was a rude shock for him to be snatched from his multihandicapped haven, in which every little triumph was celebrated and every deviation calmly corrected. In contrast, his years in the academic mainstream were ones of nearly unremitting failure. Even though his I.Q. had climbed slightly higher, he still made odd noises and had a hard time staying in a chair, his reading was below grade level and his math and penmanship were hopeless. He had two good teachers in the elementary school and one bad one, but none was equipped to do much for him. They didn't know anything about kids like him, and they hardly had enough time to devote to the rest of their students.

Most of his elementary school classmates never quite figured out what to make of him, so they kept their distance. They knew he had some kind of disability, but it wasn't one they could easily understand -- it wasn't like he was blind or lame or even severely retarded. He wasn't different enough to solicit their tenderness; he just made them nervous. Matt had a few friends who came over after school, but most of them were also marginalized, kids whose miserable family lives stunted their own ability to fit in. One of them could spend the weekend at our house without anyone in his family wondering where he was; to the outrage of all his relatives, he later turned in his father to the police for being a drug dealer. But even these guys, his fellow wretched, didn't want the stigma of being seen with him at school.

As time went on, Matt become less otherworldly but more aware of how different he was from the children in this world. He was the one who could never finish the test, the one who couldn't remember how to get from one part of the building to another, the one who completed the project last, no matter what his class was doing. I believe he was also the one child who didn't receive some kind of award or recognition at the school's graduation ceremony for fifth-graders; I noticed and hoped he didn't and fumed all the way through the ceremony.

He also had the most painful comparison right in his own home: his sister, whose abilities had outstripped his years before. When she grew old enough to get letter grades instead of "S" or "U," he was dismayed by how easy it was for her to do well. One day he came home from school and looked through a pile of her papers on the dining room table, each one perfect. "A's, all A's," he wailed, flinging her papers to the floor. "Why does she get all the sweet life?"

By the time he reached the middle school's learning disabilities program, I felt like I was sending him off every morning for a day in Beirut. It's not that the children were so much more vicious to him than they were to one another -- or to my daughter, by the time she went there -- but they had richer opportunities for torment and Matt had fewer resources to fall back on. He had always been excitable but now he had epic tantrums, both in the classroom and at home. All the therapists' advice didn't seem to help. Finally, Matt's father and I met with a psychiatrist to revisit the idea of medication -- Matt had tried Ritalin before -- and the psychiatrist talked to the three of us, then the two of us, then Matt alone. His recommendation was to get Matt out of that school. "He's depressed," the psychiatrist told us. "It's no wonder: His life is miserable."

We looked at other public school programs, then at private schools, but found no local options. Finally, we heard of a boarding school in upstate New York that sounded perfect except for the fact that it was a 12-hour drive from home. Matt and his father and I visited for a day, and Matt decided he wanted to try it for a week. The house was peaceful when we returned home; we felt a little guilty for enjoying it so much. But when I went grocery shopping, it struck me how very different life would be with my son gone. I made a spectacle of myself, weeping in the aisle with the cans of anchovies, remembering how we couldn't leave an open tin in the refrigerator when he was little or we'd find a trail of anchovy oil from the kitchen to the television. Life without him and his odd little ways seemed bleak.

His dad and I went to pick him up at the end of the week. We held each other's hands as he played basketball with a team, instead of just watching others play, and we saw people jump up and down when he almost made a point. We saw tables full of kids call his name in the cafeteria and ask him to sit with them. We saw him speak with confidence in a history class and even help another boy find the answer to the teacher's question in his book. Three girls trailed behind him as he showed us around campus, pretty girls who giggled and seemed to find him a fascinating stranger. He told us he wanted to stay at the school and I cried when we left him there, not just because I would miss him but because we had finally found a place where he fit in. Matt spent the next four years at this school, finding blissful respite from the rigors of being different.

He was a much happier boy when we moved him back home at the age of 18. As a special-education student, he was eligible for four more years of public school education. We hoped things would be easier for him in the high school than in the middle school, and they were. The high school draws kids from all the city schools, plus it pools special-education students with other districts. There was a critical mass of kids like Matt at the high school. They weren't the mainstream, but they were a sizable and exuberant stream of their own.

Matt had four good years there, which is more than you can say for most people. He made lots of friends, had two girlfriends and got work experience through the school's vocational department. He had three excellent teachers and did well in his classes. He was a minority in more than one way -- our high school is about 70 percent African-American and he is not -- and he absorbed the school's mantra of racial harmony so well that he now buys just about anything marketers pitch to blacks. I'm sure he was the only 22-year-old white guy to buy a copy of the movie "Waiting to Exhale" the day it was released, and this is just one of the things I love about him.

When he graduated, my entire family from California and his dad's entire family from New York came. At the ceremony, a school administrator warned the 3,000 people in the audience against rowdy applause, but there were enough of the people who love Matt to do the wave and to make enough noise and we did.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

After Matthew was diagnosed all those years ago, my Aunt Helen sent me a letter right away. "When Stephen was born," she wrote, "he was our greatest sorrow. Now he's our greatest joy."

Lucky me, I have many joys. It would be hard to say which is the greatest, but I can say unequivocally that Matt is one of them -- at least, most of the time. He has the kind of life that many of us wish for our children. He's in good health, eats a lot of vegetables and changes his sheets once a week. He has an apartment, a compatible roommate, two sports channels and season tickets to the Cleveland Indians. He has work that he enjoys, a job bagging groceries that showcases the almost courtly good manners he must have picked up from some of his well-bred boarding school friends. "It's been a pleasure to help you today, ma'am," I hear him say to customers as I hunker near the 40-pound bags of dog food to watch him work. His customers like him: He receives an extraordinary amount of money in tips, something I've decided must be some kind of cosmic compensation for middle school. His bosses like him, too: He was named "Employee of the Month" once and then "Employee of the Year," for which he received a gas grill the size of a golf cart.

People point to Matt's successes and tell me they have something to do with my great mothering skills. I don't feel I can take that much credit for this complex young man; I can only marvel at the ways in which my "faith in the baby" utterance was prescient. The essence of Matt was there from the beginning, written into his genetic code and embellished by the unique events of his gestation. He has his father's concern for order and cleanliness as well as -- surprise! -- his ability to charm a room full of people. He has my lack of enthusiasm for talking on the phone, but also shares both grandmothers' and my feeling for words, especially big Latinate bombs. While his reading level is about that of the average American -- good enough to read USA Today -- his speech is loaded with words like "fastidious" and "apprehensive."

Of all my father's 11 grandchildren, I think my son is the one who resembles him the most. Matt tells a joke just like my father does, he walks like my father and even his few remaining noises remind me of my father. Matt often makes a low, nasal humming sound; people who don't know him hear it from another room and think a machine has gone bad. My father also hums a lot, a kind of mysterious drone while he's gardening or washing the dishes that my siblings and I think might be "Santa Lucia." When the two of them sing at family functions, the rest of us exchange glances.

At the very least, Matt has taught me as much as I taught him. I've always been shy, with hardly enough nerve to face the world with my own imperfections. It was harder still to face it alongside my son's more unorthodox flaws, which drew attention to the two of us even when he wasn't setting off fire alarms in airports (just once) or playing with 5-year-old toys when he was 15 (many times) or doing a little Rumpelstiltskin dance as he walked down the street (still does it once in a while). I'm used to faces whipping around for a second look, and there are many times I would shrink from rather than champion him. It was hard for me to be in public with my son. It is still hard at times, and that's a terrible thing for a mother to admit.

My daughter almost never has such qualms. Jamie was raised not only with her brother's differences but also with those of his peers and has always been comfortable with the range of alterations on "normal." One of Matt's friends is the king of trivia -- ask him who sang "The Duke of Earl," who held the National League record for home runs in 1972, what the capital of Mozambique is, anything, and he knows, but he can't button his shirt. Another can't add two and two but can drive a car. Jamie learned early on that abilities don't come in clumps, that just because someone can do one thing doesn't mean he can do another. She became sensitive to these hidden surprises and was unfazed by the scorn of people who weren't.

Early on, Matt's father and I decided that the world has two camps: those who sneer at our son's differences and those quirky souls who enjoy them. It's gratifying when we meet strangers in the latter camp. A few years ago, I took Matt to a ballgame in which the Cleveland Indians clinched the championship for the American League Central Division. The Indians were playing the Baltimore Orioles, and Matt and I had great seats between home and first, just four rows from the field. The only drawback was that the row in front of us was filled with guys from Baltimore, who sat there watching glumly as the Indians hammered their team. I was afraid that Matt might piss one of these guys off. Matt is almost always on his feet. He loves to recite the provenance of each player: the various teams and positions he's played, the honors he's received over the course of his career. I often tell him to shut up and watch this game, the one we paid to see, but he's in thrall to the Game, all its players, all its moments.

At the Baltimore-Cleveland game, I was sure Matt was driving the guys in front of us crazy, especially the one guy he leaned over every time a batter took his stance. The guy would turn his head toward us slightly, which is sometimes a polite indication -- like a skunk shaking its tail -- that something bad is in the works. I kept pulling Matt down; he kept standing up again. Finally, after Matt spat out a long string of past engagements for Kevin Bass -- that he had started with Milwaukee in 1982, then moved on to Houston, then to San Francisco and then back to Houston before he got traded to Baltimore -- the guy turned all the way around. He removed his cap and set it on the seat next to him and I got ready to block a punch. But the guy grinned. "You forgot New York," he told Matt. "Kevin had a stint in New York between San Fran and Houston." Matt's mouth dropped open as he considered this, then he shook his fists around his eyes. I almost did, too.

We still run into members of the other camp, and it's still as painful as ever. Not long ago, Matt and I were at the airport waiting for a flight to California. The plane was delayed so we decided to go back to one of the fast-food counters in the lobby and get something to eat. It was crowded and I figured it would take us 10 minutes to reach the counter, but was afraid Matt still wouldn't have figured out what he wanted by the time the woman asked for his order.

"Look at the menu," I instructed, pointing to the pictures of sandwiches over the counter. "Figure out what you want now so that you don't keep everyone waiting." He rocked on his heels and hummed.

By the time the woman asked what he wanted, he was still rocking. He looked at the breakfast side of the menu. He looked at the lunch/dinner side of the menu. I gritted my teeth and stepped away.

Then a man in the line started making long, operatic sighs. He looked at the people around him to find a kindred spirit in exasperation. He settled on me, not realizing that Matt and I were together. Matt was still trying to decide. The woman at the register was patient. The man made large gestures of annoyance -- a hand thrown to his forehead, a slight kick at his briefcase. He looked at me again and groaned.

I realized I could just look away and pretend that this man wasn't making ugly faces at my son. I've done it in the past. Instead, I gave way to 24 years of anger at such boorishness. "Do you have a problem?" I asked him.

He pointed to my son. "You'd think after all this time in line he'd know what the hell he wanted. What is he, a retard or something?"

"Yes," I said. "Do you have a problem with that?"

The man was only slightly abashed. "Are you his mother?"

I nodded.

"Then you should be helping him or something. He shouldn't do this. He shouldn't be able to just stand up there and ..." He sputtered and stopped. The other people in the line regarded us carefully.

"He has as much right as anyone else to order lunch." It felt as if the whole airport was listening.

By that time, the woman behind the counter was handing Matt's order to him. Her arm hung in the air as he looked back at me, his mouth a slightly whiskered circle of wonder.

The man's face deepened from capillary-streaked pink to purple. He shuddered inside his black suit. He fiddled with his watch. "I'm sorry," he finally said, looking back up.

"No, you're an asshole." I was calm as the words left my mouth, but as soon as they did I started to cry. Matt was shocked. He almost walked away from the cashier without his change.

"What happened?" he asked several times as we walked toward our plane. He knew how unlikely it was for me to make a scene -- he makes scenes, his father makes scenes, but his mother usually keeps quiet. He touched my shoulder a few times. He unwrapped his burger and offered me a bite. He put his arm around me. Then he forgot about the confusion 20 feet back. He hummed and began to walk a little faster, his thoughts already in California, his feet already touching down in a circle of people who love him.

Shares