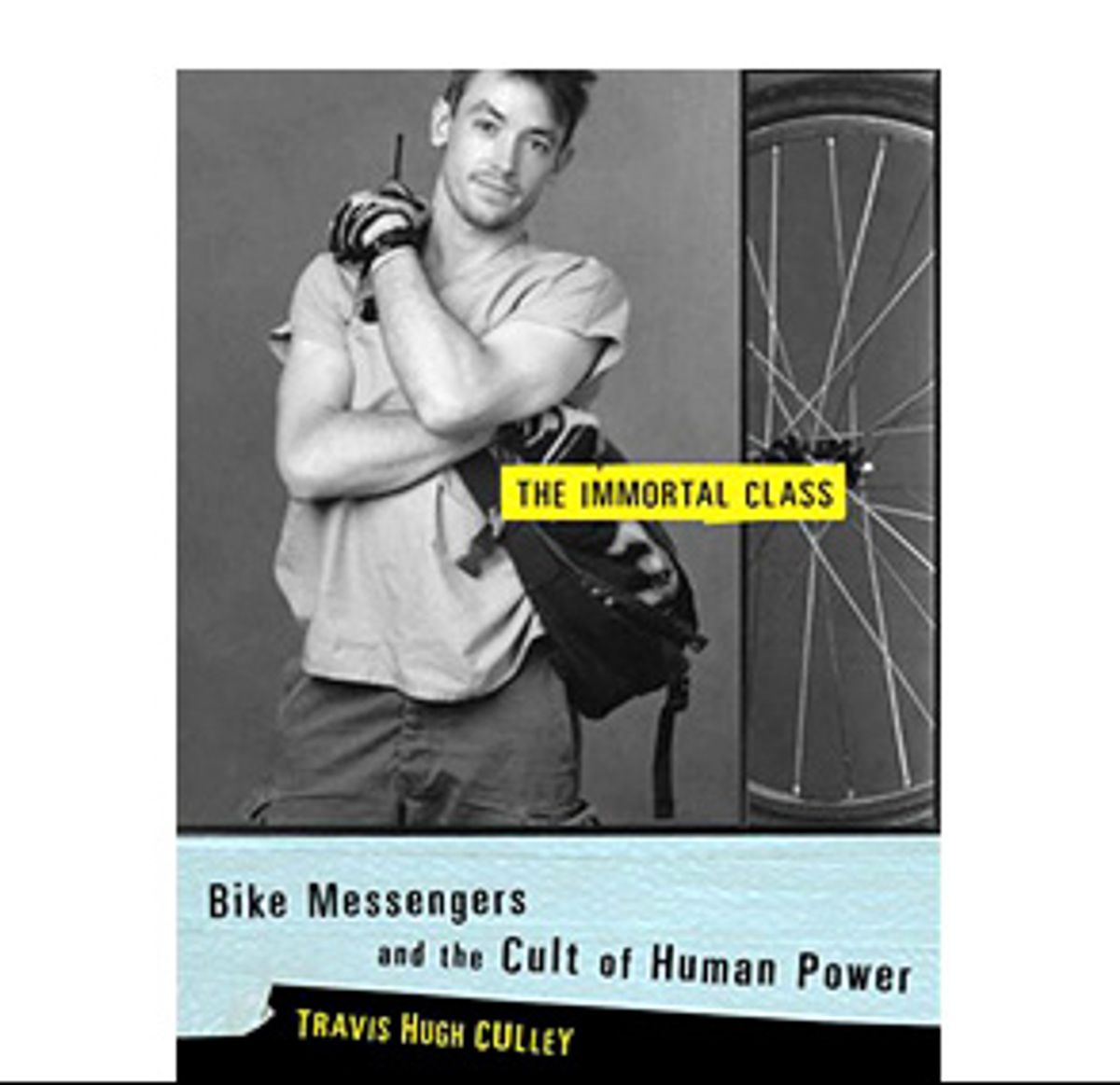

The title "The Immortal Class: Bike Messengers and the Cult of Human Power" sounds like a scarily Nietzschean proposition, but this first book by 27-year-old Travis Hugh Culley is green and crunchy to the core. It's part memoir of Culley's days as a bike messenger, part call to arms against the tyranny of cars and part love letter to the city of Chicago. Culley sees bike messengers as an emblem of "the cult of human power" -- meaning, literally, human-powered vehicles -- that, he asserts, is taking back our cities from the vicious, fume-choked, corporate-dominated clutches of car culture. That symbolism doesn't really work for a variety of reasons, beginning with the inconvenient fact that what bike messengers are zooming across town to deliver are envelopes headed from one corporate client to another. Still, even at his most dopily earnest, Culley has an energized, original voice that's worth listening to. He's Puck from "The Real World," plus poetry.

Culley makes the story of his own fairly typical journey sing. Twenty-one and broke, he comes to Chicago with a theater degree from a Miami conservatory and big dreams of starting his own theater company. The buzz of urban life after his lower-middle-class suburban Florida childhood exhilarates him, and he hits the streets and organizes "an elaborate production at a little space in Bucktown." The world seems to be his oyster. But soon he's playing to "one or two shadows in an otherwise empty theater," and he's forced to rethink his plan.

Refusing to give up, he does grunt-labor jobs and desperately tries to keep his theater dreams alive. Things finally take a new turn when a girlfriend takes him to a bike rally spearheaded by Critical Mass, a group that holds loosely organized anti-car protests in cities around the world. "This was the theater I had come to Chicago for," Culley writes in an inspiring moment of lemonade-making. Soon he's a convert, captivated by the radically democratic potential of bicycles to transform urban life. The next time he's desperate for cash, he decides to apply for work as a bike messenger.

Culley writes best about the physical experience of the job. "Even in deep sleep, the world hurled forward at me," he says at one point. "I would have dreams that amounted to nothing but snapshots over a feeling of general motion -- the flash of an aluminum drainpipe, a bird on the grille of a building's ventilator duct, an upturned garbage can, a missing license plate, an ink stain, a pile of boxes on the other side of a dirty glass windowpane, then crack -- I was being thrown over a mailbox." From his bike messenger's perspective he conveys the thrill, beauty and harsh logic of urban life with a sharp, poetic eye: "I have learned to see in the city a distinct sense of order, a special geometry, a realm of necessity behind each unplanned lunge and skid."

Yet Culley never seems to fully grasp the interesting duality of the bike messenger's role. Is he an anarchist free spirit, a thorn in the side of suburban, car-dependent America, or is he just another exploited cog in the corporate machine? It's an inevitable tension that Culley halfheartedly acknowledges but can't bring himself to embrace; what could have been a productive paradox in his book instead remains a nagging contradiction.

Culley celebrates the messengers' jazzy argot and tightly bonded subculture and explains why they must break traffic rules: "A messenger following a commuter's level of caution and defensiveness would destroy his livelihood, insult his character, and impede his right to the road." But he also displays an admiration for order and efficiency that would warm the heart of any MBA. "It shocks me how our market system can be so easily threatened by the culture of temps and administrative assistants," he says at one point when a delivery is fouled up by a dazed temp. Of course, his point is that companies should invest more in their workers, but you have to wonder whether his barely hidden respect for smoothly run corporate ventures will one day land Culley in a window office somewhere, rather than on the front lines. Yet even at his most inadvertently proto-capitalistic, Culley has a fresh-faced idealism that charms, not least in placing bike messengers at the center of his vision for the ideal future city, "a sustainable Chicago covered with bike-only streets, quiet trains, and a patient, car-free, delivery-based roadway."

Occasionally, Culley lapses into dorm-room philosophizing, as if he's writing his urban studies senior thesis. ("The interplay of social instability and industrial omnipotence has turned the American urban experiment into something unhealthy, undemocratic, and ecologically unsound.") But despite its bumpy stretches, "The Immortal Class" is a pleasant surprise for anyone who wishes a greater range of young writers were being published these days. Culley goes for the sweeping Whitman-esque gesture over the self-conscious postmodern curlicue every time. He's blissfully free of self-pity. His body is a source of power and adventure, not a mystifying font of confusion and humiliation; he has pushed himself physically, sweated and bled and collapsed at night in exhaustion. He has a healthy ego but he's not a narcissist -- he's primarily interested in the world beyond his own small experience. And if the economic downturn continues, the next wave of young workers to arrive in cities could do worse than follow Culley's example of how to live on very little money and keep your spirits up and your integrity intact.

Shares