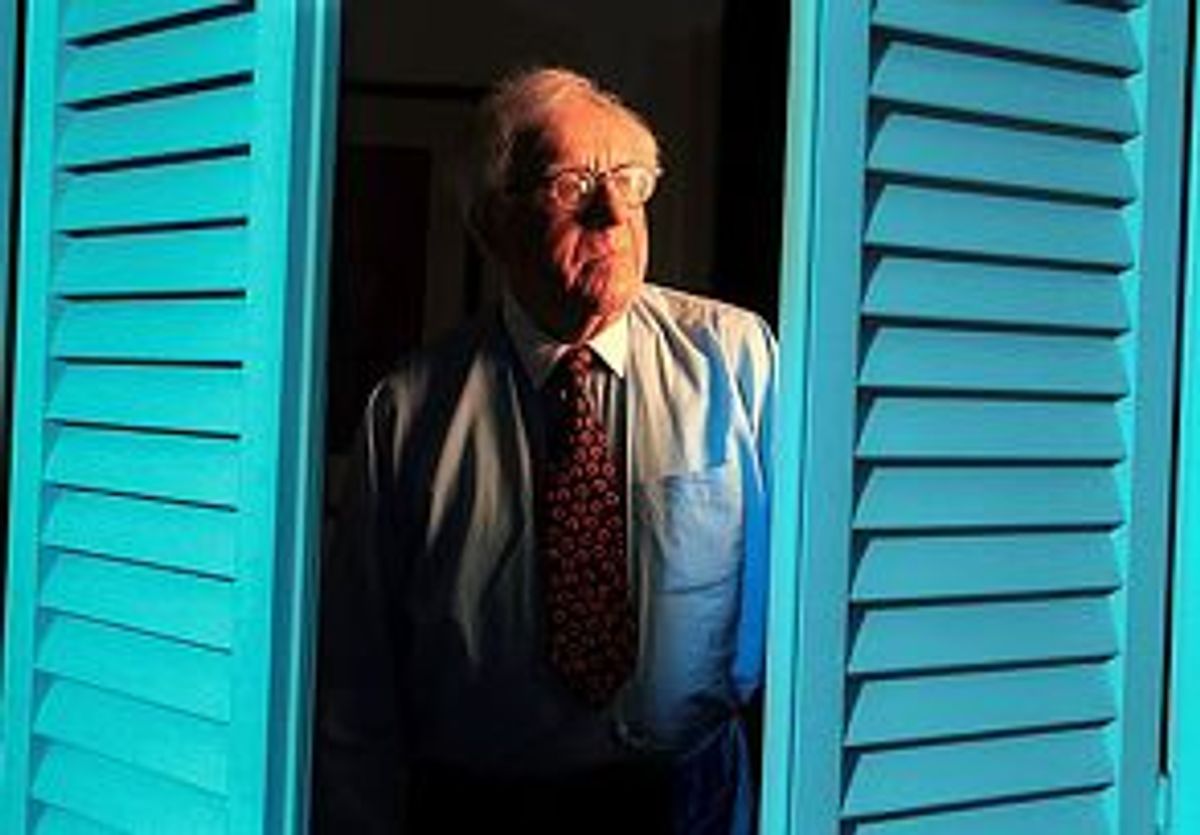

Author Ray Bradbury, now 81 and recovering from a stroke, has recently become the most sought-after writer in Hollywood.

Renny Harlin ("Die Hard 2," "Cliffhanger") has signed to direct Bradbury's time-travel adventure "A Sound of Thunder." Frank Darabont ("The Shawshank Redemption," "The Green Mile") will direct new productions of "The Martian Chronicles" and "Fahrenheit 451." Bradbury is also adapting his short story collection "The Illustrated Man" for the Sci-Fi Channel and says he's writing a script based on his novella "Frost and Fire" that will be filmed next year. And the literary establishment has also recognized him recently. Last November the National Book Foundation gave its Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters to Bradbury.

The unprecedented interest by Hollywood in Bradbury's work is coincidentally timed to one of the author's major publishing anniversaries. Fifty years ago, the first printed version of "Fahrenheit 451" debuted in Galaxy Science Fiction magazine.

A future shock masterpiece, "Fahrenheit 451" was largely overlooked during recent millennial sci-fi retrospectives in favor of other dystopian works such as "1984," "2001: A Space Odyssey" and "Brave New World." The novel's famed central premise (a society where firefighters burn censored books) has long suggested a metaphorical fantasy rather than serious prognostication.

Kerosene-spraying firemen aside, a closer look at the 1953 novel shows Bradbury nailed the new millennium perfectly. There's interactive television, stereo earphones (which reportedly inspired a Sony engineer to invent the Walkman), immersive wall-size TVs, earpiece communicators, rampant political correctness, omnipresent advertising and a violent youth culture ignored by self-absorbed, prescription-dependent parents.

Far from an abstract nightmare, "Fahrenheit 451" is now disturbing because its culture no longer seems disturbing. And its dated terminology, such as calling headset radios "seashell ear thimbles," constantly remind modern readers the novel was written 50 years ago and that its culture -- our culture -- was intended only as a horrifying possibility.

One "Fahrenheit 451" prediction was the technological evolution, and moral devolution, of television news. In the novel, a fireman protagonist accused of hiding illegal books is pursued by a carnivorous news media seeking to satiate the blood lust of home viewers. As the fireman flees down the street, chased by helicopters, he sees himself through his neighbors' windows, running on their television screens.

The day after news helicopters pursued O.J. Simpson fleeing in a Ford Bronco, a New York Times columnist noted that the chase was the "real-life fulfillment" of "Fahrenheit 451."

Bradbury points to a more current example. "Look at the Chandra Levy case," he says. "It's become a Star Chamber. The major networks, the cable networks, they're being prosecutors. They're judges and jurors and executioners. Well, c'mon, that's ridiculous. But they're doing it."

The fictional roots of "Fahrenheit 451's" vision of mass censorship even resemble the complaints of modern media critics.

In the novel, Fire Captain Beatty explains to Montag, the conflicted fireman, that their government didn't ban reading. Books were simply marginalized as an increasingly inoffensive media and a growing population embraced infotainment at the expense of "slippery stuff like philosophy or sociology."

Says Beatty: "Bigger the population, the more minorities. Don't step on the toes of the dog lovers, the cat lovers, doctors, lawyers, merchants, chiefs, Mormons, Baptists ... The bigger your market, Montag, the less you handle controversy, remember that! ... Magazines became a nice blend of vanilla tapioca. Books, so the damned snobbish critics said, were dishwater. No wonder books stopped selling."

Bradbury scored yet another prognostication bull's-eye in his 1953 short story "The Murderer," wherein a man is imprisoned for wrecking "machines that yak-yak-yak." The most offensive devices were the "radio wristwatch" communicators.

Said the electronics murderer: "... my friends and wife phoned every five minutes. What is there about such 'conveniences' that makes them so temptingly convenient? ... Convenient for my office, so when I'm in the field with my radio car there's no moment when I'm not in touch. In touch! There's a slimy phrase. Touch, hell. Gripped! Pawed, rather."

As retribution, the murderer jams radio wristwatch signals on a commuter bus and delights in the "terrible, unexpected silence" he creates: "The bus inhabitants faced with having to converse with each other."

Substitute a few product terms and "The Murderer" could be passed off as modern nonfiction. True, Dick Tracy also wore a primitive cellphone on his wrist, but Bradbury intuitively grasped how annoyingly demanding and oddly isolating such technology could become.

Today Bradbury continues to criticize modern innovations, putting him in the seemingly contradictory position of being a sci-fi writer who's also a technophobe. He famously claims to have never driven a car (Bradbury finds accident statistics appallingly unacceptable; he witnessed a deadly car accident as a teen). He is scornful of the Internet (telling one reporter it's "a big scam" by computer companies) and ATMs (asking, "Why go to a machine when you can go to a human being?") and computers ("A computer is a typewriter," he says, "I have two typewriters, I don't need another one").

By mocking the electronic shortcuts and distracting entertainment that replace human contact and active thinking, Bradbury shows his science fiction label is misplaced. He cares little for science or its fictions. The author of more than 30 books, 600 short stories and numerous poems, essays and plays, Bradbury is a consistent champion of things human and real. There is simply no ready label for a writer who mixes poetry and mythology with fantasy and technology to create literate tales of suspense and social criticism; no ideal bookstore section for the author whose stories of rockets and carnivals and Halloween capture the fascination of 12-year-olds, while also stunning adult readers with his powerful prose and knowing grasp of the human condition.

One secret to Bradbury's lifelong productivity is that his play and his work are the same. When asked, "How often do you write?" Bradbury replies, "Every day of my life -- you got to be in love or you shouldn't do it."

His new novel, "From the Dust Returned," will be published by William Morrow in October. When I phoned his Los Angeles home for a 9 a.m. interview, Bradbury was thoughtful and cranky, and told me he'd already written a short story.

What makes a great story?

If you're a storyteller, that's what makes a great story. I think the reason my stories have been so successful is that I have a strong sense of metaphor. And that with my stories, you can remember it because I grew up on Greek myths, Roman myths, Egyptian myths and the Norse Eddas. So when you have influences like that, your metaphors are so strong that people can't forget them.

You've been critical of computers in the past. But what about programs that aid creativity? Do you think using a word processor handicaps a writer?

There is no one way of writing. Pad and pencil, wonderful. Typewriter, wonderful. It doesn't matter what you use. In the last month I've written a new screenplay with a pad and pen. There's no one way to be creative. Any old way will work.

What about video games? If young Ray Bradbury from 1940 were here today, would he play video games where a person can experience a simulation of space travel?

That's male ego crap. I never cared for pinball games when I was 18 or 19. Video games are a waste of time for men with nothing else to do. Real brains don't do that. On occasion? Sure. As relaxation? Great. But not full time and a lot of people are doing that. And while they're doing that, I'll go ahead and write another novel.

What's an average work day like for you?

Well, I've already got my work done. At 7 a.m. I wrote a short story.

How long does that usually take?

Usually about a morning. If an idea isn't exciting you shouldn't do it. I usually get an idea around 8 o'clock in the morning, when I'm getting up, and by noon it's finished. And if it isn't done quickly you're going to begin to lie. So as quickly as you can, you emotionally react to an idea. That's how I write short stories. They've all been done in a single morning when I felt passionately about them.

You suddenly have five films based on your work going into production. A coincidence?

I've been waiting around a lot of years -- that's the answer. I'm going to be 81 in a few weeks. So if you wait around long enough, things happen. At least in my case.

Which adaptation are you most looking forward to watching?

Oh, all of them. I love all of the arts. I love motion pictures. I love stage. I love theater. I'm putting on an Irish play here in L.A. in about three weeks based on my experiences in Ireland about 45 years ago when I was working for John Huston on "Moby Dick" ["Green Shadows, White Whale"]. And then "Fahrenheit 451" will be on the stage in a small theater in New York early next year. And my "Dandelion Wine" musical will be opening in Florida in January. So I got a lot of theater projects going too.

You've been a longtime fan of movies. What is the last Hollywood picture you enjoyed?

I haven't seen many recent films. I usually wait until the end of the year. I'm a member of the Academy and they send me 80 or 90 films on tape so I can watch them at my leisure. One of my favorite films in the last three years was "As Good As It Gets" with Jack Nicholson. Brilliant film. I've seen it eight or nine times. It's absolutely perfect. Great screenplay. Helen Hunt is wonderful. Nicholson is incredible. The dog is beautiful. The whole thing is a wonderful, wonderful exercise. Beyond that, films like "Analyze This" with Robert DeNiro. Charming, wonderful and amusing film. And I love to look at things like that after seeing some of the violent films we've made. The sick films. The negative films we've made. Beyond that, I rent a lot of old films again and again.

What about modern science fiction films, such as "The Matrix"?

I haven't seen that one yet, but I gather it's one of the better ones. Most films these days are too long. The screenplay is everything. Otherwise I think we're all just going to go look at the monsters, aren't we?

In your short story "A Sound of Thunder," the outcome of a close presidential election was altered when a time traveler squishes an insect in a prehistoric age. Do you think we were a squashed butterfly away from getting Al Gore?

That's right.

What do you think of President Bush?

He's wonderful. We needed him. Clinton is a shithead and we're glad to be rid of him. And I'm not talking about his sexual exploits. I think we have a chance to do something about education, very important. We should have done it years ago. It doesn't matter who does it -- Democrats or Republicans -- but it's long overdue. Our education system is a monstrosity. We need to go back and rebuild kindergarten and first grade and teach reading and writing to everybody, all colors, and then the whole structure of our education will change because people will know how to read and write.

There's so much competition for a young person's attention nowadays. For the record, why is reading still important?

Are you kidding? You can't have a civilization without that, can you? If you can't read and write you can't think. Your thoughts are dispersed if you don't know how to read and write. You've got to be able to look at your thoughts on paper and discover what a fool you were.

Many years ago, I heard you speak and during the question period you chastised an audience member who asked about the decline of reading. You countered that books were more popular than ever. Do you still feel that way?

Well, there is no reading in some areas. Look at our students. What is our future going to be if you have all the people in school right now who don't learn to read and write? It's easy to teach reading and writing in kindergarten, so for chrissake do it. There are a lot of books selling today, but the number of people actually reading and digesting and thinking I gather would be quite small when compared to the population.

I was surprised you said in your Playboy interview that corporations were the only way to revitalize impoverished communities.

Well that's true. They've got the money; nobody else has it. People like myself know the secret of cities and how to build them. I give these ideas to corporations and they build them and they revitalize sections of cities -- like Century City [in Los Angeles]. But I've had to tell them numerous times over the past few years to build it in human terms. Hollywood Boulevard needs to be torn down and rebuilt completely in terms of human beings. Right now, it's completely dead.

What do you mean "in human terms"?

Places to eat. The secret of cities is eating. In Paris there are 20,000 restaurants. You go down Main Street, people are sitting out and people-watching -- that's what I'm talking about.

The House recently passed the Human Cloning Ban of 2001.

Why would you clone people when you can go to bed with them and make a baby? C'mon, it's stupid. Stalin and Mao had a great idea about cloning -- they killed 80 million people and what's left is your clones. If you don't like the way the world is put together you just kill everybody. What you got left is the master race. We have more important things to do than these silly ideas. Let's clone people in kindergarten and teach them how to teach reading and writing.

Is it better to have the future authenticate your predictions or would you have preferred society to have proven you wrong?

I would have loved to have been proven wrong, yes. I do not like what is going on in our society. Our education system, as I've said, is a total disaster.

Were you deliberately trying to prognosticate or simply tell a good story?

It's a combination. If you're living in your time, you cannot help but to write about the things that are important. As long as [social criticism is] part of the structure and muscle and blood of the book, it's OK. As long as you don't become too self-important, politically. The best advice I ever got was from Somerset Maugham's book "Summing Up," which I read in high school. His advice was: Don't look left or right, look straight ahead, get your work done, enjoy your work, do what you want to do, not what someone else wants you to do.

And that's been the story of my life. Not pleasing my friends, not pleasing any editor, just myself.

Shares