As U.S. ground troops begin fighting in Afghanistan, there is one thing that they can expect: land mines -- as many as 10 million of them.

You can step on a land mine while clambering through the rubble of a building in Herat or Kandahar, trudging through the mountains near the borders of Iran, or crossing a farm in the lowlands. You could be surprised by a hidden mine in a strategic military position: say, the roof of a government building, in a power station, or around an airport. Or you might trigger one simply by straying to the side of the country's major roads.

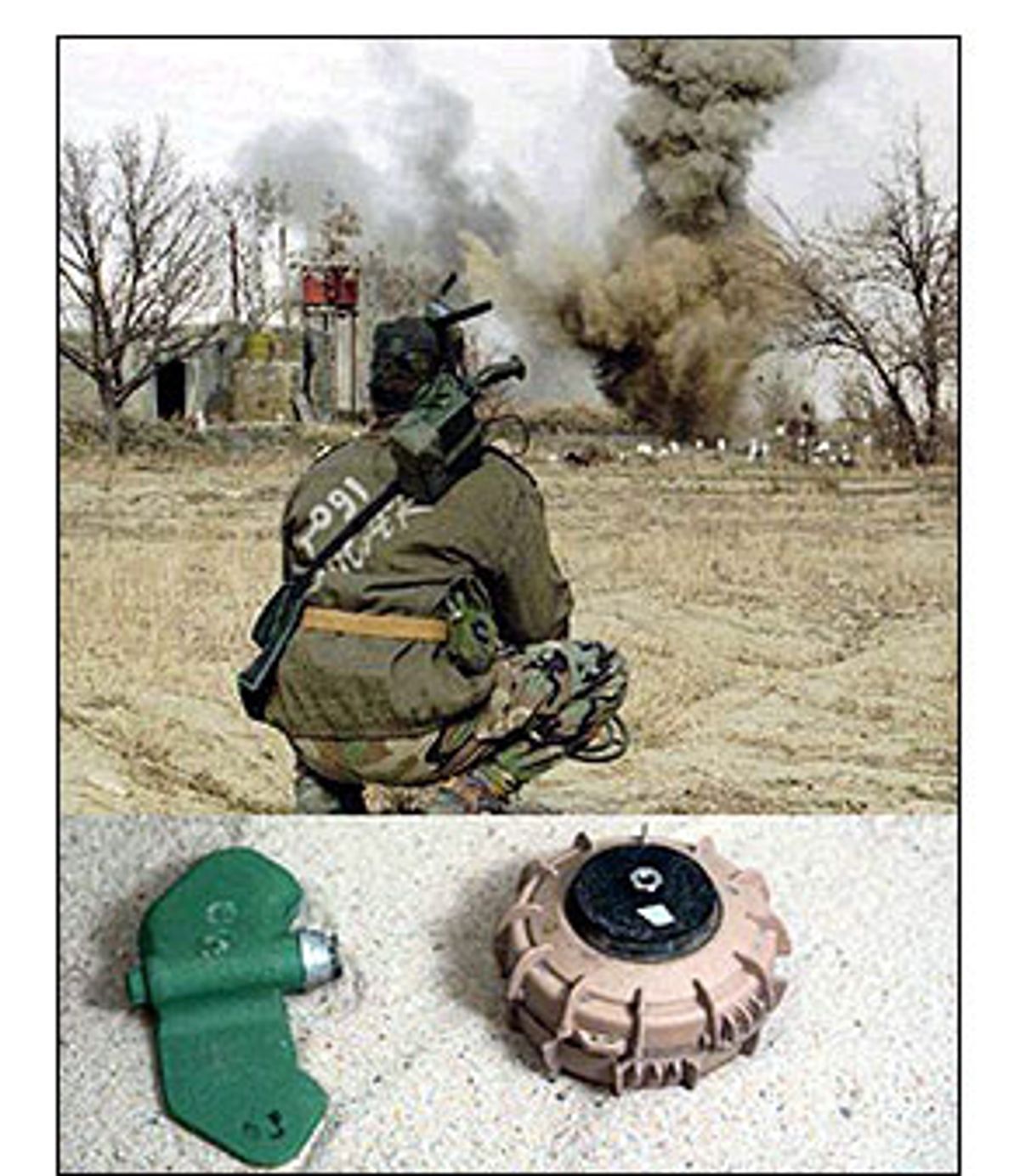

For the last decade, Afghanistan has boasted the largest and best-coordinated de-mining campaign of any country in the world -- some 5,000 locals have been employed by the United Nations and other international organizations to scour the landscape and detonate any mines they find. Over 1.6 million land mines and UXOs (or "unexploded ordnance," such as bombs that didn't detonate on impact) have been discovered and removed over the last 11 years by eight different mine clearance programs.

If you saw "The English Patient," you know the drill: The method hasn't changed since World War II. Some de-miners do have metal detectors, but many of these are out of date and of limited utility. The ground is already full of metal shrapnel, thanks to years of fighting, which makes metal detectors useless; and many of the most modern mines are ceramic, in order to avoid detection. The international community has funneled nearly $25 million a year to de-mining programs in Afghanistan, and experts had optimistically predicted that "high-priority" areas would be cleared within seven years if that funding kept flowing.

But all de-mining programs in Afghanistan came to a screeching halt Sept. 12, thanks to terrorist attacks on the U.S. blamed on Osama bin Laden. In fact, the first reported civilian casualties of the U.S. bombing campaign were four Afghan U.N. de-mining workers -- bomb-disposal experts who had stayed in the area to help get rid of any UXOs.

Despite the de-miners' diligence, Afghanistan remains one of the three countries in the world most affected by mines, comparable only to Angola and Cambodia. Some 732 million square meters of land across the country still contain mines -- 11 percent of the land of Afghanistan, according to the Mine Action Information Center -- and more are being discovered every day. Every month, 88 Afghans die from mine injuries.

Experts used to optimistically estimate that at the rate the de-miners were working, the country's most critical areas would be cleared of mines within five to seven years. But thanks to the new war, all bets are off. Not only have de-mining efforts come to a halt, but the country now has to worry about new mines being laid by both the Taliban and the Northern Alliance.

The ever-present land mines are expected to slow down the efforts of American ground troops heading in to the country. But while soldiers who are about to enter Afghanistan will most certainly be endangered by the mines that lie underfoot, it is the Afghan civilians who will ultimately suffer the most. What the military leaves behind as they rush through the terrain, the locals will have to live with.

"As applied, these are now weapons of terror which primarily affect civilians," says Richard Kidd, who in 1998 and 1999 worked in Afghanistan as the deputy program director of the United Nations Mine Action Programme for Afghanistan. "The impacts are horrific."

There are 42 different varieties of land mines currently in use in Afghanistan. During the last two decades of warfare, mines were laid anywhere there was fighting -- which, of course, was just about everywhere. Most mines were laid by the Russians during the war, but they were also used by the Northern Alliance and the Taliban. The Northern Alliance continues to use land mines today, according to the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), but the Taliban claims to have eliminated land mines from its arsenal: In 1998, the Taliban's supreme leader issued a decree that mines were un-Islamic, and banned their use, stockpiling and trade.

Most land mines are invisible to the human eye. They lie buried under a centimeter or two of dirt, or hidden in piles of rubble, lurking just below the surface of the earth and waiting to detonate at the slightest pressure. Typically, the only way to tell if a land mine is present is if a de-mining team has already surveyed it and marked the area with signs. Otherwise, locals who have discovered a minefield in their area (generally, because neighbors have already been injured) have to create their own cryptic maps of the danger zones -- marking the hazards they know about with a pile of twigs, or a rock that's painted red.

Not surprisingly, the human toll of land-mine use is boggling. Last year, 1,100 people in Afghanistan died from mine injuries, and 40 to 100 more lost legs, eyes, hands or other limbs each week. This, fortunately, is an improvement over previous years -- in 1993, there were 20 to 23 casualties each day. Consider these to be lowball numbers, though: Since many mine deaths and injuries go unreported, most experts guess that the real number of land mine-related casualties is at least twice as high.

Even though many land mines are designed to maim rather than kill soldiers, the injuries that they cause are often lethal for civilians. The average person who steps on a mine will bleed to death within five minutes; often there is simply no one else around to offer assistance, or else those who are present are afraid to walk into the minefield and risk their own lives to help.

"One type of land mine, the blast mine, takes a fully grown man's leg and breaks it as if it had been smashed on both ends. It normally will not kill an adult man, if there is first aid and medical treatment. Unfortunately, in Afghanistan those things don't exist, so they often bleed to death or get septic and die," says Kidd. "The second type is the fragmentation mine, which contains lots of metal shrapnel and BBs. When the mine explodes the metal goes flying out like a hand grenade. In most cases, these will kill one or more individuals."

Over half the land mine casualties in Afghanistan have been children, who are at high risk because they usually gather the family's firewood or take care of the animals. Many young children perished because they tried to pick up the tragically colorful "butterfly mines," which were airdropped by Russians and lay on top of the ground, unintentionally resembling toys. "The butterfly mine was dropped in different colors -- white for snow, green for forested areas, yellow for sand," explains Mary Wareham, coordinator of the Land Mine Monitor for Human Rights Watch and the ICBL. "Its unique shape and colors were attracting children: It's enticing to a child who does not have a lot of other things to play with."

Those who do survive a land mine injury face a future nearly as bleak as death itself; in a country like Afghanistan, losing a limb often means losing your livelihood. "If you have a family living on the edge of starvation and the husband becomes an invalid and can't work, the entire family is now at jeopardy of starvation. The family could be broken up and the children sold," says Kidd. "For those who do survive there's a tremendous sense of guilt -- now they've become a burden rather than a contributing member of the family. They are outcast many times, or they sometimes literally will themselves to die."

Still, many crippled Afghans do forge onward with the help of a precious, if ill-fitting, fake limb -- some 210,000 Afghans are currently living with land mine injuries.

Humans are not the only victims of land mines. Some 75,000 animals -- sheep, goats, donkeys, camels, horses and cows -- died last year because they grazed in a minefield. The loss is profound in a country constantly on the brink of starvation. Farms are incapacitated because fields and irrigation ditches were tilled with mines, making it impossible to grow crops.

Although over a million Afghans have been given mine-awareness training, they typically aren't taught how to de-mine their way out of a minefield -- it's simply too time-consuming and dangerous.

Instead, the 5,000 official Afghan de-miners have the onus of clearing the entire country of mines. It's an arduous and expensive endeavor: First, advance surveying teams have to talk to locals, who generally have the best sense of where local "danger zones" might lie. Then, a team with mine-sniffing dogs (Belgian Malinois and German shepherds) will determine the perimeter of the minefield, and mark it off with masking tape and signs. Within six months, a team of de-miners -- attired in masked helmets and bulletproof vests -- will descend on the area and go over it inch by inch, lying face down on the ground and poking at the dirt with a long metal knitting needle. If they hit something with the needle, they clean around it to make sure it's a mine, scrape the dirt off the top, and then blow it up in place.

It's decidedly dangerous work; four de-miners were killed last year, and another eleven injured. "The de-miners get the worst injuries -- because they are to their face and hands, not just their legs," says Wareham.

But the benefits of the job are also manifold. De-miners are some of the best-paid workers in Afghanistan (in fact, one mine authority begged Salon not to print the de-miners' salaries, lest they be targeted for kidnapping and extortion by impoverished locals). In a country that has been decimated by mines, the de-miners are also highly respected members of society. "The de-miners are heroes," says Kidd. "They spend their lives doing dangerous things to help other people in their country." (The caveat, adds Wareham, is that many do it from guilt: "De-miners on the program are often former soldiers who laid the mines and feel a debt to go and clear them," she says).

The mine clearance groups in Afghanistan also have to contend with the Taliban, which is now targeting them for their valuable equipment.

"On October 15, some armed personnel of Taliban authorities forced its way [into] one of our site office in Mazar-e-Sharif," Fazel Karim Fazel, the director of the Organization for Mine Clearance and Afghan Rehabilitation (OMAR), complained in an e-mail this week. "They beat our guards, broke the locks of the doors and entered into the office. They looted all the office equipment and left nothing behind. The threats have also been given to the other offices of OMAR, to hand over all the vehicles and communication systems to the Taliban, otherwise they will snatch them by force."

Not only will the mine programs now have to cope with lost equipment and lost time, but they will also need to retrain their staffers to deal with a host of new weapons being dropped by the U.S.-led coalition forces. Many local mine clearance experts are going to Kosovo for a quick education on the new bombs, mines and UXOs, says Wareham. "They have to establish a body of knowledge on weapons that are being used, since they have to go out and see what has been dropped and what hasn't exploded and clear it as quickly as possible."

There is deep concern, for example, about "cluster bombs" -- a favorite tool of the coalition forces, which also proved a problem for mine clearance teams in Kosovo because of their high failure rate. Like the colorful butterfly mines which were such a problem for children, unexploded cluster bombs are yellow and orange and small and round. "They are on the ground, not under the ground, so they are visible," says Wareham. "And they are incredibly lethal; they are so full of shrapnel and have so much explosive force that you almost never survive."

The question plaguing some land mine experts is whether more mines will be laid as part of the new conflict. It was already known that the Northern Alliance had been laying new mines during the last year, but it's not clear how many they are using currently. Says Wareham, "We were fairly certain there must be land mine use continuing. But the United Nations says that it's in a limited area along the front line, and that it's decreased significantly from the past, when they didn't even think about laying hundreds of thousands of mines." And despite the Taliban's promises to respect the Mine Ban Treaty, experts suspected that they had still been using land mines provided by Pakistan; any last vestiges of reluctance to use mines have, presumably, vanished now that the Taliban is facing a massing enemy on the ground.

And although much of the Western world has signed the 1997 International Mine Ban Treaty and promised to eliminate the mines from their arsenal, the United States has not, which leads some watchdogs to worry that mines might be a part of its strategy in Afghanistan. Last week, Human Rights Watch issued a statement calling on the United States "not [to] use antipersonnel land mines in Afghanistan" after the New York Times reported that the forces had dropped CBU-89 Gators, a mixed-mine system, into Afghanistan (the report of the Gator use was later recalled, however).

But others, such as Kidd, brush off the likelihood that this will happen. "The logic of the mines in the U.S. inventory are to blunt massed armor and infantry attacks in restricted terrain; the mine is a weapon whose utility is declining," he says. "It's for mass infantry attacks, and the Taliban forces don't have the capacity to do that. Especially when logistics are such a challenge, I would rate the chances of U.S. forces using mines at about zero -- it doesn't make sense and it costs too much.

"The current conflict isn't making things worse, as far as I know; it doesn't make sense," he adds. "The mine problem is already on the ground and will presumably be a hazard for any soldiers that go in there."

Experts say that it's impossible to estimate how great a problem mines will be for American troops; it will depend on the nature and scope of troop deployment. But American infantry will certainly be more at risk than indigenous Taliban fighters, simply because they will have no idea where the local minefields are, nor understand the locals' cryptic piles of twigs and painted rocks. It would seem intuitive to expect land mines to hinder troop movement.

"The mines aren't marked, aren't mapped, and there is no indication that a U.S. soldier would expect to show them that it's mined. It would definitely slow them down," says Wareham. "And it would be a lot more scary -- there's a psychological reason they are used; they do instill a sense of fear in soldiers. And the mines are designed to maim rather than kill, so the soldier is a bigger burden as a whole -- they have to get him out of the mine area and stabilize him and get him to facilities. All that takes time from what they are doing."

It would be tragically ironic if American soldiers died because of land mines that were laid by mujahedin warlords 15 years ago, when the U.S. was supporting them in their bid against the Russians. And it is even more tragic to think that troops on any side of this conflict might now be busily laying down new land mines in fields, cities and mountains which had only recently been cleared by the heroic Afghan de-miners. Unfortunately, only time -- and casualties -- will tell whether the latest skirmishes on Afghan soil have made this country's plague of land mines any worse.

Shares