During Ken Burns' lifetime tour of all things archetypally American, it was probably inevitable that he make a stop at Mark Twain. Twain may or may not be our greatest writer, but he is unquestionably our most beloved -- and the most quintessentially American. He grew up on the banks of the great river that flows through the heart of the country, and after a self-inventing career as a printer, riverboat pilot, prospector and newspaperman, ended up a New England grandee and the nation's gaudiest literary legend -- a picaresque red, white and blue life made even more familiar by the fact that he then squandered it all. But above all, Twain is ours in a way no other American writer is because of his language -- that is, our language. If Twain single-handedly invented American literature, as Ernest Hemingway and a number of other people who have some standing to say such things have claimed, it was because he heard our voices true and gave them back to us.

Burns' "Mark Twain" makes this essential point clearly and forcefully. At the beginning of the film (which is in two parts, each two hours long), Ron Powers, a Twain biographer who is one of the most eloquent of the film's many experts, says, "[His] genius was for speaking the voice of America." The playwright Arthur Miller comments that Twain "wrote as though there had been no literature before him" -- a marvelous and marveling tribute from one great writer to another. Hal Holbrook, longtime star of the famous one-man stage show "Mark Twain Tonight" -- whose almost personal relationship with Twain gives his comments emotional force -- says, "He made American speech something to be admired." And so the stage is set for the story of a writer whose swaggering mastery of the vernacular and willingness to talk about America's hidden shame, race, not only changed our literature but, as the film observes, changed the way we think about ourselves.

"Mark Twain" gives a vivid sense of this screamingly funny, deeply sad, daughter-worshipping, money-mad, unbelievably fortunate, tragedy-plagued border ruffian and genteel New Englander who gave American literature -- to use the highest term of praise in Huck Finn's lexicon -- its "sand." Though it is not without flaws, it leaves you, like all good biographies, with the paradoxical feeling that its subject can't really be summed up, but that you know him anyway -- and that you know him in a way that he didn't, couldn't, know himself.

"Mark Twain" will inevitably be compared to Burns' larger documentaries. This is somewhat unfair: "Jazz," "Baseball" and "The Civil War" were not only much larger subjects, Burns had the advantage of being there first. Mark Twain, a legend in his own lifetime and the subject of a torrent of biographies and scholarly and critical works, is well-trod ground indeed. A fairer comparison would be to Burns' "Thomas Jefferson." Both are fine films -- well-researched, solidly written, accompanied by Burns' usual well-chosen selection of fascinating and sometimes remarkable archival photographs. But "Mark Twain" -- at least its first episode -- is more gripping, if only because Twain is a far more robust (if not more complex) character than the elusively cerebral Jefferson.

"Mark Twain" succeeds in pulling off a difficult task: bringing together popular history and the subtler genre of literary biography. Burns, his longtime collaborator Geoffrey Ward and co-writer Dayton Duncan are sophisticated enough, and have assembled a smart enough team of Twain scholars and writers (the commentators include Russell Banks, Shelley Fisher Fishkin, John Boyer, Jocelyn Chadwick and Dick Gregory) to convey the drama and pathos of his creative struggles and successes without resorting to simplistic pop-psychological analysis.

From the start, the emphasis is on Twain the humorist. This makes sense, since whatever else he is, Twain is the funniest major writer in the history of world literature. "I was born the 30th of November, 1835, in the almost invisible village of Florida, Monroe County, Missouri," "Twain" drawls at the beginning of the film. "The village contained 100 people and I increased its population by one percent. It is more than many of the best men in history could have done for a town. There is no record of a person doing as much -- not even Shakespeare. But I did it for Florida, and it shows that I could have done it for any place -- even London, I suppose."

The film deals sensitively with Twain's early life in Florida and Hannibal, Mo., revealing his early and crucial exposure to black slaves on his uncle's farm, including one named Uncle Dan'l. "I think that race was always a factor in his consciousness, partly because black people and black voices were the norm for him before he understood there were differences. They were the first voices of his youth and the most powerful," says the writer David Bradley. (The film glosses over the fact that Twain acknowledged that there was an unbridgeable gulf between him and the black friends of his youth.) It moves on to his job as a printer's apprentice at age 14, his grand achievement in becoming a Mississippi pilot and his agony -- the first of many sorrows that would befall this fearless, restless, softhearted genius and glorified scam artist.

The stagecoach trip he took out West with his brother Orion (that years later was completely transformed for his comedic purposes in "Roughing It") is dealt with gloriously: as the narrator reads a wonderful passage in which the stagecoach-riding Twain extols the virtues of "ham and eggs and scenery," along with a good pipe, as all that is required for human happiness, we see the open West rolling by. Then come his rollicking days as a newspaperman in Virginia City and San Francisco (described by Powers as a "great proto-psychedelic, counterculture newspaper society out West"), followed by his weeks of slinking about in shame and his near suicide after being fired from his San Francisco newspaper job. (The "slinking" days are accompanied by what appear to be some of those wonderful misty, murky Arnold Genthe photographs of Chinatown.) He gets his big break with "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County" -- his first review describes him as "foremost among the merry gentlemen of the California press."

Twain began the lecture career that was to save him financially after a trip to Hawaii. His advertisements use the portentous five-stacked-headlines style of the day to excellent effect:

A splendid orchestra

Is in town, but has not been engaged.

Also,

A den of Ferocious Wild Beasts

Will be on exhibition in the next block.

Magnificent Fireworks

Were in contemplation for the occasion, but the idea has been abandoned.

Twain followed his lectures, which were a smash hit, with a trip to Europe that yielded "Innocents Abroad." He met his sweet, frail wife, Livy, from a wealthy East Coast family, and wooed and won her despite the reasonable suspicions of her family that he was a drunken, lecherous frontier bum. The film gives an extraordinary account of his encounter with an old ex-slave named Mary Ann Cord, whose story of having her children taken from her Twain turned into his first "serious" piece.

But the heart of "Mark Twain" comes when it turns to "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn." Everyone weighs in: Dick Gregory points out that before "Huckleberry Finn" nobody "had to listen to a conversation from a black person." The eloquent Russell Banks, discussing the famous passage in which Huck says "All right, then, I'll go to hell" after he defies his conscience and decides not to turn Jim in, says that that single line offers "the possibility of redemption" from America's founding sin of racial injustice and "makes the hair on the back of my head stand up." Arthur Miller, quoting Twain's dictum that "the difference between the right word and almost the right word is the difference between lightning and the lightning bug," celebrates Twain as a writer whose apparent easy mastery of language conceals a poet's meticulous craft. (One of my personal Twain hair-standers: As Huck searches his memory for reasons to turn in Jim, Twain writes: "But somehow I couldn't seem to strike no places to harden me against him, but only the other kind." Twain came to hate Christianity, but is there a more deeply Christian -- or Jewish, or Muslim, or Buddhist -- sentence than that in literature?)

But it is perhaps William Styron who says it best. Pointing out that for some reason no one has ever been able to completely explain, this story of a white derelict and a black runaway slave going down a river on a raft resonates with people everywhere, Styron says that "out of his genius, Twain found a metaphor for the tragicomedy of life" -- and, in the end, created "a hymn to the solidarity of the human race."

At times, the analysis in "Mark Twain" seems slightly superficial. Addressing one of the major issues in Twain criticism, the famous dialectic and tension between "Samuel Clemens" and "Mark Twain," Ron Powers points out that the bourgeois Samuel Clemens used the disreputable "Mark Twain" as a kind of dark power he would summon up to do his creative bidding. But the schism between the two sides of the writer, the toll it took, its possible relation to both Twain's creative decline and his peculiar obsession with fame and wealth, aren't explored in any depth. Twain's humor offers a similar case: The film treats it as a kind of displacement or compensation for his darkness and bitterness. While there is no doubt some truth in this, it's a bit facile.

Of course, it isn't easy to incorporate literary criticism into a television biography -- or, for that matter, into biography of any kind. Still, there are ways to do it. Burns likes to use on-camera commentators, and they are effective here (in fact, they're more eloquent, by and large, than the commentators in "Jazz"), but one wonders why he didn't make judicious use of more written Twain criticism. Neither nonspecialists like Ward and Duncan nor any on-camera commentator is going to be able to match the eloquence of, say, E.L. Doctorow's introduction to "Tom Sawyer" in the Oxford edition of Twain's collected works.

But these are minor quibbles, easily forgotten in the pleasure of seeing a prime-time television show that gives the process of artistic creation center stage. Take the scene when Twain, working in his cottage at Quarry Farm, suddenly taps into a treasure trove of long-lost boyhood memories. "The fountains of my great deep are broken up," Twain (as read by Kevin Conway) says in wonder. "The old life has swept before me like a pageant. The old faces have looked at me out of the mists of the past. Old hands have clasped mine ..." Our awareness -- and perhaps Twain's -- that the discovery would fuel his major works, providing him with what the great Twain biographer Justin Kaplan memorably called a "usable past," gives this scene a sense of joy touched with grandeur.

And, of course, there are many "Burns" moments -- those times when a perfect visual image and a telling narrative come together, allowing you to simultaneously grasp the arc of his life and imagine you're seeing through Twain's eyes. It's an epiphany unique to this form, at once conceptual and visceral. When the young Samuel Clemens talks about how when he was young all he wanted to be was a Mississippi steamboat pilot, for example, an exquisite shot of a faraway steamboat at dusk fills the screen -- the image at once an embodiment of metaphorical, disembodied memory, like Proust's madeleine, and a real image such as Twain really saw, a life he really lived.

And there is Twain's face. It's an extraordinary face, familiar, likable, wise, brash, tender, irascible -- a face that seems almost infinitely expressive, that you can read almost any emotion into. When Clemens sets off to be a riverboat pilot, we see a photo of his face at age 22 -- a big, fearless, rough-and-tumble, get-out-of-my-way beefsteak of an American face. When the narrator describes how the young Clemens felt responsible for the death of his younger brother Henry, who was scalded to death when the boiler of his steamboat exploded, and we hear Clemens' anguished words, we see the same image again -- and suddenly it is the face of a young man with a broken heart . The face of the old Twain, too, lives on the edge between utter sadness and irrepressible feistiness.

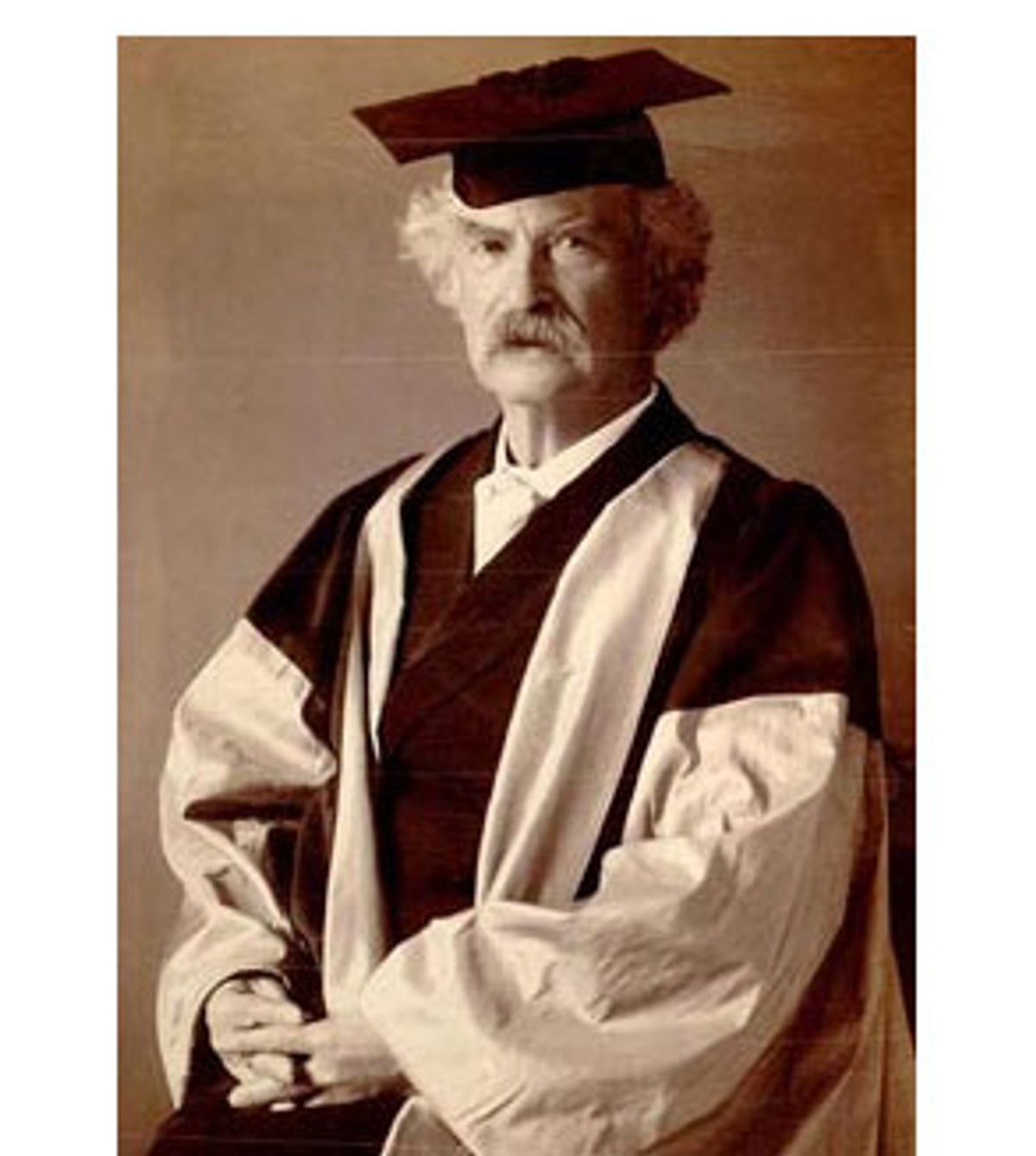

The film doesn't duck Twain's dark side. It acknowledges that he had a violent temper (a neighbor was shocked when he threw dozens of shirts out the upstairs window because one was missing a button) and, more troublingly, hints that he wished his beloved daughters would remain children forever. (A photo of him at his daughter Clara's wedding is frightening: dressed to upstage the bride in his honorary Oxford gown, he looks as grim as death.) The man who would for hours tell his three little girls stories based (in prescribed order) on certain items in the library was also the man who vanished for months at a time, who could be distant and cold, who demanded adulation. To their credit, the filmmakers allow these contradictory elements to stand, without trying to explain them.

The only serious criticism of "Mark Twain" concerns the arc of its story, which emphasizes Twain's ultimately tragic later life at the expense of a deeper exploration of his most important and dynamic creative and personal period. Episode 1 ends in 1885 with the U.S. publication of his masterpiece, "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn," when Twain was almost 50 years old and had written virtually all of his major work -- "Innocents Abroad," "Roughing It," "Life on the Mississippi," "Tom Sawyer" and "Huckleberry Finn." All of Episode 2, therefore, takes place when Twain's creative career was in decline -- a slow decline, one punctuated by highlights such as "Pudd'nhead Wilson" and the bitter, fantastic outbursts of his God-detesting old age, but decline nevertheless.

The second part deals with a sadder man than the lovable picaro who muscled his way on pure, irrepressible talent to the top of America's literary heap. We see Twain's obsession with becoming even richer than he was, his abysmal business sense (Arthur Miller has some perspicacious comments on why artists are too imaginative to ever be good businessmen) and, above all, the heartrending deaths of his beloved daughter Susy and wife, Livy. We also witness one of the great stories in American literary history, the grueling around-the-world lecture tour that the 60-year-old Twain undertook to pay off his enormous debts -- a tour that ended four years later with the 64-year-old writer returning home to a hero's welcome, acclaimed as "the bravest writer in America." But mostly, we witness a man whose lights, as the novelist Russell Banks puts it, have been going out as he got older. (Banks notes memorably that in his early days, when he shed light in all directions, Twain was a "wise guy who's wise.")

In short, it's a long downer, and maybe longer than it needed to be. On the other hand, it's true. Burns and his collaborators' approach implicitly asserts that a writer's personal life is just as worthy of interest as his work. It's a perfectly reasonable position -- and certainly Twain's entire life was remarkable. And from a practical point of view, the "tragic fall" of Twain's later life makes it a good story -- where else were they going to break Part 1 to keep viewers coming back for Part 2?

Still, I can't help but wish that Twain's creative decline had been condensed and that some of Episode 2 had been devoted to taking deeper looks at books like "Life on the Mississippi," "Innocents Abroad" and "Roughing It" -- all masterpieces in their own right that don't quite get their due here. A discussion of "Life on the Mississippi" could have provided an opportunity to examine both the muscular rightness of Twain's descriptive prose and his irritating tendency to pad great books with inferior material. (Every Burns film is always going to be just a tiny bit sentimental: Just as Twain's racial attitudes are slightly elevated, nothing is said here about how Twain, even at his best, had a wee admixture of the hack in him. Hence the lame ending of "Huckleberry Finn." Actually, it's an endearing trait. Would we want "the Lincoln of our literature" to be an ice machine like Flaubert?) "Innocents Abroad" is noteworthy for its created persona, the smartass rube who allows Twain to crack wise without missing a beat. And "Roughing It" remains quite simply one of the weirdest and wildest books ever written, a ridiculous "true" romp of a memoir whose tour de force balancing of fact and fiction, real self and bogus "reality" anticipates gonzo journalism. Both of those books could have grabbed more of the spotlight.

Instead, we are told more about Twain's harebrained business schemes than we need to know. Visually too, the film falls off in the second part: There are endless shots of Twain's Hartford mansion, inside, outside, in fall, in summer. Mostly, though, we watch the unutterably sad story of the tragedies that befell Twain in his later life, and his anguished and, frankly, rather bizarre literary reaction. "Mark Twain" never quite explains just why the death of his wife and his daughter destroyed Twain's belief in a benevolent God and led him to write the weird, hopeless, clunkily metaphysical tales of his late career -- but I'm not sure that any other biography has, either.

He went down to silent sadness in the end, even his Lear-like rages falling from him. But that isn't what one remembers, or should remember. One should remember Twain the irrepressible, the life force, braggard and trickster and bully-ram blowhard and great poet of our tongue, bouncing off fate's ropes like Muhammad Ali, again and again.

"Mark Twain" does justice to this great, flawed, deeply lovable writer and great, flawed, deeply lovable man. And it leaves the viewer just a little bit prouder of, and more filled with wonder about, the strange country, maybe still young, that could produce a man who did so much, and lived so long.

Shares