In 1993, when I worked for the Korea Times English Edition in Los Angeles, I wrote a story with the headline "A Mother's Sorrow." In it, I described the first time I met Mrs. Kim, then 43, a former nurse who immigrated to the United States from Seoul in 1971. She sat on the floor of her living room and sipped a cup of ginseng tea. She said the brew would bring her strength as she coped with the fact that her 16-year-old son had just been charged with murder. He had been arrested with four other youths in the grisly 1992 New Year's Eve slaying of Stuart Tay, a 17-year-old Chinese American who lived in Orange County.

"The whole Korean community is unable to sleep," said Kim. "They all cry for me. They felt like it was their own child's incident." I knew what she meant. Many other Korean-American immigrant families wondered: If this could happen to a middle-class Christian family like the Kims, could it happen to any of us? I had my own hidden agenda. Wasn't my curiosity about this murder case driven by my fear of not being able to protect my own child from all negative peer pressure?

Mrs. Kim's shock and bewilderment were easy to understand. The details of the crime were unbearable; the possibility of her son's involvement, intolerable. Tay and five high school students had been involved in a plot to rob a computer salesman who worked out of his Anaheim home. But Tay fell out of grace with his peers for using a false name to protect his own reputation. In retaliation, they bludgeoned him with a baseball bat and sledgehammer before dumping him in a grave dug at least a day before his slaying. The newspapers described how one of the murderers poured rubbing alcohol into Tay's mouth and duct-taped it shut. Tay then suffocated as the harsh liquid filled his lungs.

My son Tommy actually knew Mrs. Kim's son. Both of them had attended the same Korean-American summer camp in the San Bernardino Mountains. "He wasn't my friend," insisted Tommy when we talked about the murder over dinner. I could tell that he was disturbed. How could someone he knew commit such a gruesome crime?

"What was Mrs. Kim's son like?" I asked.

"Kinda quiet. A kiss-up with the counselors," said Tommy.

"Did you hang out with him?"

"Nah, he was too nerdy."

"Did he seem susceptible to peer pressure?"

"I don't know, Ma! Stop asking me so many questions."

I went to Mrs. Kim for answers, hoping to interview her for a feature story. Surprisingly, when I rang her doorbell, she invited me in and allowed me to ask her personal questions. The Kims' lifestyle mirrored many aspiring Korean immigrants' version of the American dream. She and her husband, a doctor, were well respected in the Korean-American community and in Orange County. Their then 18-year-old daughter attended the University of California at San Diego. They lived in a two-story home, drove a Mercedes-Benz sedan and a Jeep Cherokee, and could afford summer vacations like the one they took in 1992 to Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. Life was sweet -- until the police informed Mrs. Kim of her son's murder charges. "I wanted to die right away," she told me. "But if I died, who's going to take care of my son? For his well-being, I have to survive."

As I talked with her, I learned that she was an active school parent. She also served as former president of Sunny Hills High School's Korean Parent Support Group in 1991. In 1992, she received an award from the Orange County Human Relations Commission for promoting cultural awareness and dialogue. The recognition suddenly seemed painfully ironic. About two months after the killing, Superior Court Judge Francisco Briseno ordered Mrs. Kim's son, then 17, to be tried as an adult. He was convicted and sentenced to state prison for 25 years to life.

I can't remember how many times Mrs. Kim and I spoke to each other after the sentencing. But our lives crisscrossed again a year later: My son Tommy, then just 16, collapsed and died while playing basketball at school. His sudden death hit the local news -- on TV and in print. The Los Angeles Times ran three stories: "Teen-Ager Collapses During Gym Class, Dies," "Heart Failure in Youth Likely Is Congenital" and "Friends Recall Boy's Zest for Life." As soon as Mrs. Kim learned of Tommy's death, she drove to our home. She walked into our living room with a five-gallon jar of seaweed soup -- known in Korean as miyok-kuk. "Here," she said, "this is for you. It will give you strength during these dark days."

The only other time anyone had given me miyok-kuk was during the happiest days of my life -- right after the birth of my older son, David. A different Mrs. Kim made me the same soup 20 years earlier, in Bergenfield, N.J. And she told me, "Here, this is for you. It will give you strength in the days ahead." Koreans believe that new mothers are better able to lactate when the nutrients of miyok-kuk compensate for blood lost during childbirth. And sure enough, when the first Mrs. Kim gave me a pot of seaweed soup, I produced milk like Elsie the Cow.

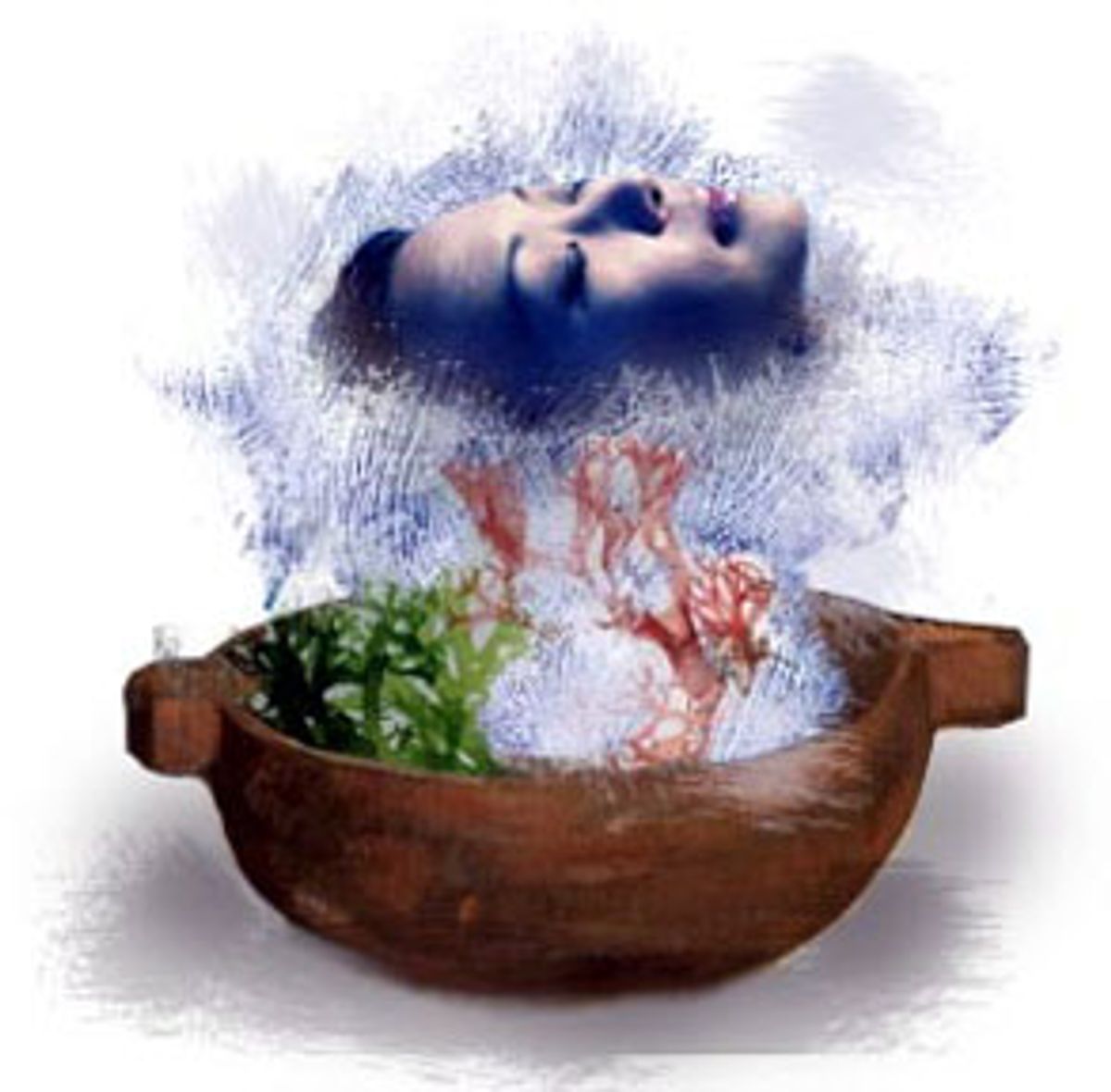

Seaweed after the birth of one son; seaweed after the death of another. In both cases, the Mrs. Kims prepared Korean comfort food -- savory nutrients originating from the Land of Morning Calm -- in a gesture of shared motherhood.

There were few Korean traditions or customs I actually turned to during my earliest years of grief, but the miyok-kuk soothed my tender stomach. Only later did I learn that the soup, aside from providing healthy doses of calcium, iodine and other minerals, also had a role in appeasing the supernatural. In the olden days, after bathing a newborn, Korean women prepared a samshinsang -- an altar for the three divine Shaman beings. They boiled white rice and brown seaweed soup, and brought these gifts to the altar. The samshinsang was supposed to stay in a corner of the mother's bedroom, near her head, conveying gratitude to the three gods, who represent the Shaman concept of magic that influences fertility from conception to birth.

Six years after the imprisonment of her son and the death of mine, Mrs. Kim called me out of the blue. As it turned out, she suffered from extreme depression about her son's imprisonment. We talked about him for most of the conversation. "He's doing better," she said. "But I can't visit him as often because he's been transferred to San Diego." I told her: "I'm sure he knows that you love him." And then she apologized. "I'm so sorry. I called to make you feel better. And here, you've given me comfort instead."

Mrs. Kim sounded terribly weak, like a first-time mother after childbirth -- fragile from the loss of too much blood. I wanted to make her a pot of homemade miyok-kuk, filled with dark green ribbons of nutrients to invoke the powers of more forgiving shamans. I wanted to hand over the brew and say, "Mrs. Kim, this miyok-kuk is for you. It will give you strength for the years ahead."

Shares