"I am one of the thousands of readers who was not only entranced but helped through life by the work of Henry Miller," wrote François Truffaut in 1975. "And I suffered at the idea that cinema lagged so far behind his books as well as behind reality. Unhappily, I still cannot cite an erotic film that is the equivalent of Henry Miller's writing (the best films, from Bergman to Bertolucci, have been pessimistic), but, after all, freedom for the cinema is still quite new."

If only Truffaut had lived to see Alfonso Cuarón's "Y Tu Mamá También (And Your Mother, Too)." Erotic freedom has remained such an elusive ideal for movies that fresh, frank treatments of sex still have the power to shock us, to exhilarate us. Watching "Y Tu Mamá También" is something like what it must have been like for readers in the '30s first encountering Henry Miller. There's the same shock, the same exhilaration -- not just a sexual thrill, or the thrill of watching an artist work without a net, but the exhilaration of feeling yourself alive. Miller contended that "Tropic of Cancer" was "a kick in the pants to God, Man, Destiny, Time, Love, Beauty." He was only partly right. That book, disrespect for duty and authority and piety sweating out of its every open pore, was also an ode -- and an often tender one -- to the joy of living, even the joy to be found in the agony of living. The Miller figure, most often characterized by empty pockets, a grumbling stomach and a hard-on that wouldn't quit, is also, as he says, "the happiest man alive."

Right up until its melancholy coda (captured by the casual elegy of Frank Zappa's "Watermelon in Easter Hay" on the soundtrack), "Y Tu Mamá También" is one of the most joyous movies I've ever seen, and one of the handful of great erotic films the movies have given us. Audiences in Mexico responded by making it the biggest hit in the country's history. It deserves to be just as big a hit here.

A sexually explicit comedy may come as a shock to audiences who know Cuarón from his two American movies, "A Little Princess" and "Great Expectations." It shouldn't, though. Both of those films were adaptations of wonderful books, Francis Hodgson Burnett's children's classic, and the Charles Dickens novel (which had been famously filmed by David Lean in 1946). What was striking about the two films was their atmosphere of rich sensuality. "A Little Princess" hummed with its young heroine's belief in the power of her imagination, the thing that saves her from cruel treatment during her sojourn in a girls' school. In one scene, she and the young black maid she's befriended wake in their shabby attic bedroom to discover that, while they slept, a rich man's servant has transformed it into a palace of silks and canopies, with plush robes and slippers and mouthwatering food awaiting them. It's the moment of deliverance that occurs in all great fairy tales turned into a catalog of pleasures, the two girls like miniature rajahs basking in their sudden good fortune.

And the updated version of "Great Expectations," which turned Dickens's Pip into an aspiring artist in '90s Manhattan, transfromed the hero's ardor for the unattainable Estella into a verdant eroticism. The British critic Robin Wood -- one of the few critics to get the movie -- identified it as one of the rare book-to-film adaptations faithful to the spirit of its source while managing to be its own creation. He called it "splendid" and said "the adaptation is so free that, after a while, one ceases to think of Dickens at all."

Freedom, which in terms of moviemaking can be said to be the filmmaker's refusal to fear risk, is the key to "Y Tu Mamá También." Written by Cuarón's brother Carlos, and shot by the great Emmanuel Lubezki (who also shot "A Little Princess," "Great Expectations" and Tim Burton's "Sleepy Hollow"), the movie puts us in the horny, sweaty skin of its two adolescent protagonists. They are Tenoch (Diego Luna), the privileged son of the country's rich, corrupt secretary of state, and his buddy Julio (Gael García Bernal), the lower-middle-class son of a single mother. These two are gentle, sweeter-tempered cousins to the louts played by Gérard Depardieu and Patrick Dewaere in Bertrand Blier's road comedy "Going Places." Free for the summer while their girlfriends are off to Italy, Tenoch and Julio are bursting out of their jeans. Tenoch makes his girl promise not to bed down with any Italians. But her plane has barely left the ground before he and Julio are talking about bird-dogging girls at an upcoming party.

Cuarón has said the movie is "about two teenage boys finding their identity as adults and ... also about the search for identity of a country going through its teenage years and trying to find itself as an adult nation." With the throwaway shots of gun-toting soldiers routinely stopping vehicles along country roads, the boys' teenage years look a lot more fun than their nation's. Cuarón presents the boys getting high, whacking off, goofing off; they're primal forces who haven't surrendered to the respectability or casual corruption that surrounds them.

It's not that Cuarón doesn't realize that they will have to grow up and make compromises, or that he's unaware of their self-centeredness or their small hypocrisies. Cuarón loves Tenoch and Julio for their direct, uncomplicated ability to feel pleasure. The hormone-fueled esprit that drives them is its own love song to the possibilities of life. They may be juvenile -- grossing each other out by farting in the car, or laying on adjoining diving boards, each calling out encouragement to the other while they masturbate ("Salma Hayek!" "Ahhhh, Salmita!"), but they're not jaded or cynical or burned out. Hovering on the verge of obnoxiousness, they are, for the experience under their belt, basically grubby innocents. Like dirty-minded virgins, they're excited by each joint, every beer, every chance for sex as if it were their first time. On middle-aged men, the funk of cigarettes and beer and sweat and sex smells of failure; on Tenoch and Julio it's the perfume of youth.

Befitting a tale of discovery, "Y Tu Mamá También" is a road movie. At a lavish wedding thrown by Tenoch's parents, they meet Luisa (Maribel Verdú), Tenoch's Spanish cousin by marriage. They regale Luisa with tales of a paradisiacal, off-the-beaten-track beach called La Boca del Cielo (Heaven's Mouth) and tell her she should join them on their trip to find it. A few days later she calls them to ask if the offer is still open and together they set off. There's just one hitch: As far as the boys know, the place doesn't exist.

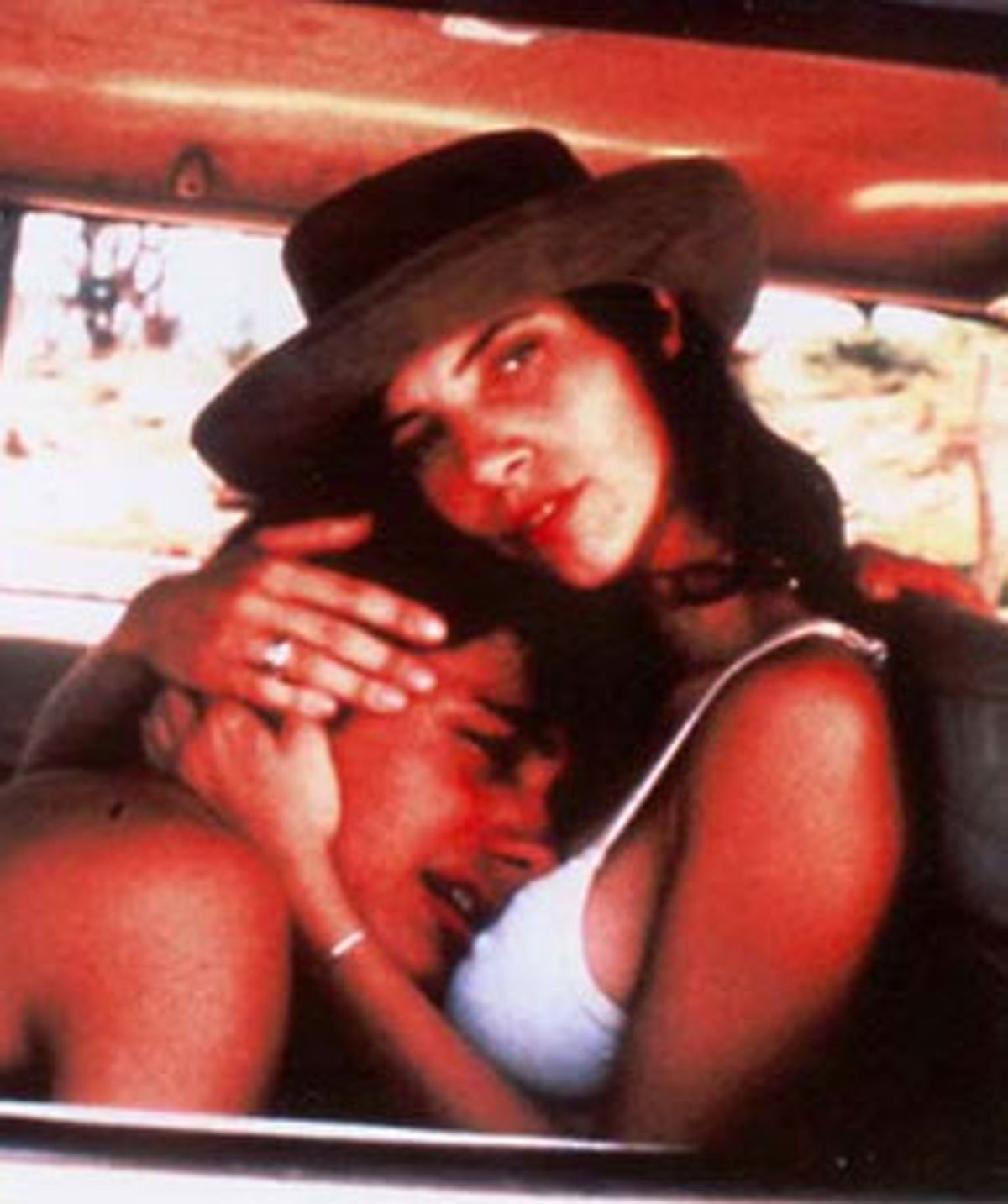

Traveling through the Mexican countryside in Julio's sister's car, the three begin an exploratory dance. Luisa asks them about their girlfriends, about what brings them pleasure, about their various exploits, and the two teenagers, eager to impress this "older woman" -- who's only got about 10 years on them -- brag and laugh with the overconfident boisterousness of baby seducers. It's a good front; these kids are as scared as they are turned on. Inevitably, it's Luisa who ends up seducing both of them. That may sound like the setup for an adolescent male fantasy (and there's nothing inherently wrong with a filmmaker presenting a character's sex fantasies on-screen), but Cuarón is after something more complex.

Part of the shocked, huffy response to Bertrand Blier's sex comedies "Going Places" and "Get Our Your Handkerchiefs" came from critics and audiences who couldn't see that, male fantasies though those films were, the male characters were consistently the butt of the joke. The pain and turmoil of the women characters was always treated seriously, even as Blier's subject was the ways in which men are baffled by women. Cuarón isn't baffled by Luisa. One look at her husband, the puffed-up novelist Jano (Juan Carlos Remolina Suarez), is enough to tell you hers is not a happy union. Jano is the sort of needy mama's boy who calls Luisa up after cheating on her and begs teary, drunken forgiveness. Cuarón is, however, lovingly attentive.

You understand why Luisa takes the chance to head off with Tenoch and Julio. Her attitude toward them is a sort of incredulous delight. She knows they've got rockets in their pockets and it makes her laugh -- both at them and at herself for palling around with them. And though Cuarón shares the boys' happy, greedy voracity, it's through Luisa's eyes that we come to see them -- annoying and endearing at the same time.

The movie gets great mileage out of the joke that boys at the height of their sexual potency are often woodpeckers in the sack. Neither Tenoch nor Julio last very long in their couplings with Luisa, and though she treats them tenderly, we can see the bemused frustration on her face. And, as Blier did, Cuarón takes her unhappiness very seriously. He understands there's more at stake for her than there is for the boys, that her grab for happiness has much more desperation than the boys' innocent hedonism (even if he waits to reveal all that's at stake for her). The different levels at which they perceive their spree is the source of the movie's best jokes and its most moving passages.

"Y Tu Mamá También" is unusual in that we get to see more of Tenoch and Julio's bodies than Luisa's. Even that becomes an example of the differences in their awareness, an expression of the boys' unself-consciousness. They are in awe of Luisa, and Cuarón understands that she's the powerful one in the trio. When their misbehavior gets to be too much, she lays down the law and, like obedient puppies content to frisk at her feet, they comply.

Finally, though, what this trio share is more important than what divides them. Some of the happiest moments in the movie are the three of them driving through the countryside, fast food wrappers littering the car, Luisa's feet up on the dashboard, intoxicated with the sun and the freedom of being on the move. The lovely section where they reach their fabled beach and camp with a fisherman and his family has the feel of an extended idyll, an elemental existence that drowns out the static in their heads and makes them all purr with contentment. The questers have found their seaside Eden. And it all pays off in the climax, a go-for-broke moment that's both a great, daring joke and the deepest affirmation of the movie's faith in the glories of lust.

The fearlessness of "Y Tu Mamá También" isn't Cuarón's alone. I don't think it's too much to say that the performances of the three lead actors attain the stature of offhand bravery. For the movie to work, they have to be as free and unembarrassed on-screen as their characters are, and there isn't a false note among them. It would have been easy for Luna and Bernal to caricature Tenoch and Julio (or to make the frequent mistake of youth movies and hold them up as avatars of wisdom). They're good enough to allow us to be exasperated with them without once risking our affection. And Maribel Verdú is extraordinary, balancing pleasure and sadness in a way that suggests the depths Luisa keeps hidden inside herself. When her wide, beautiful mouth opens in a radiant smile, she becomes the movie's carnal madonna, a patron saint of sexual generosity.

Maybe because honesty about sex is such a perilous road for any artist to take, inviting accusations of shallowness or voyeurism, movies that attempt to deal honestly with sex remain rare, and they almost always feel like we're seeing something new. "Y Tu Mamá También" makes you feel the slate is being wiped clean and that the movies have once again become a place where anything is possible. The last scene is the culmination of the undertow that flows all through the movie in sudden bits of omniscient narration, not unlike the stray thoughts that popped up in Godard's '60s movies. Cuarón leaves it open as to whether the memory of their adventure with Luisa will be one the boys will cherish their whole life, or whether it will haunt them in years to come as a symbol of their lost freedom. But even that uncertainty can't dispel the liberating joy in Cuarón's embrace of pleasure, in his dispensing with guilt.

I've talked about saints and madonnas, about putting faith in the erotic. Without falsifying the movie's raunchy free spirit, its combination of fairy tale and dirty joke (the title being the ultimate capper), I'd like to suggest that the movie's unabashed impulse toward life is a sort of praise-giving, that, for Cuarón, what's sacred here lies in what's profane. "In every poem by Matisse," Henry Miller wrote in "Tropic of Cancer, "there is the history of a particle of human flesh which refused the consummation of death." "Y Tu Mamá También" realizes that the deepest prayers come from that refusal.

Shares