Imagine my surprise at receiving an invitation to a dead man’s birthday party; who knew they even threw those anymore? Birthday boy L. Ron Hubbard — LRH, in Scientology speak — would’ve been 91 if he hadn’t “dropped his body” right smack in the middle o f Reagan’s second term. The Church of Scientology wanted me to come help celebrate.

A few days after I RSVP’d, a Scientology P.R. flack called back to calmly rescind my invitation. Why? I asked. Hadn’t he himself invited me to learn more about his Tr avolta-tainted faith after I savaged the film adaptation of LRH’s “Battlefield Earth” in the Philadelphia Weekly? Didn’t he relish the opportunity, at last, to represent for “Dianetics”? Actually, no. If I were to write about Scientology again, he implied, it would be on Scientology’s terms. Though he offered to meet me personally to explain LRH’s mysterious thrall, he said my attending the birthday bash “would not be appropriate.” OK, so I’d have to crash it.

A smiling greeter clad in black-and-whit e evening attire ushered us into the Ben Franklin-founded Philadelphia Free Library. Inside the white marble great hall, Hubbard’s candy-colored volumes sent more sober tomes packing. Posing as a married couple, an accomplice and I claimed a table for fou r in a basement hallway outside the building’s bathrooms. Some 80 eager buffet grazers and a blissed-out guitarist strumming white noise outside the men’s-room door transformed the place into a South Bend church social circa 1969.

We weren’t seated l ong before a suited man approached as much to check us out as to proselytize. He asked how we’d wound up there. By invitation, of course. He asked if we’d read “Dianetics,” which true believers and snickering cynics know as the Church of Scientology’s bib le.

“Parts,” I admitted. Which was true. In fact I have my very own copy, complete with Post-its marking favorite spots.

The suited man — I’ll call him Ken — told us the bea uty of “Dianetics” is that it’s completely literal. He then explained his work with the church, which consists mainly of performing “audits” on people in a process that has nothing to do with taxes, but instead involves a handy piece of Atomic Age technol ogy called an e-meter. This device, which measures galvanic skin response, is similar to a lie detector. It is supposed to measure the brain’s resistance to memory-triggered engrams. After some 150 hours of auditing in which senior Scientologists tried to isolate the physical remnants of his emotional pain, Ken had been declared clear of pesky engrams (or became “a clear,” a liberated spirit) and graduated to performing audits himself. Ken showed off the Medic Alert-type bracelet that advertises his statu s. I asked what exactly happens during an audit. “At those levels,” Ken said, “it’s confidential.”

Soon another couple joined us at the table. Both born-again Christians, they had been chatted up by Ken, too. But he fed them better stuff: According t o Scientology, we learned, all of us were once spiritual blank slates — thetans — thousands of years ago. Over time we became corrupted by everyone from the ancient Romans and the crusading Christians of the Middle Ages, clear through to Pavlov and Freud and all their dirty psychiatry-spouting peers. The story goes on, but alas, the show hadn’t even started. e

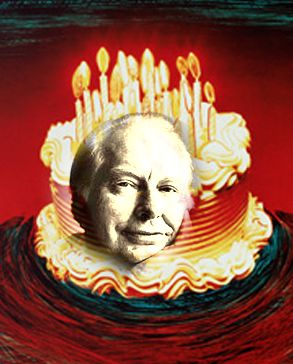

Before the main event, a local “org” leader, looking like a Martha Stewart stunt double, took the stage for a bit of motivational speaking. In a scene straight out of a Leni Riefenstahl film, she led the crowd in a fist-pumping hip-hip-hooraying of an LRH bust and a poster-size photo of the man himself standing alongside a lighted birthday cake. In lock-step harmony, the enthusiastic crew enunciated a hearty “yeah” to each canned pep rally question.

Would they like to hear about how the local org grew this past year? “Yeah!” How ’bout the hours of auditing performed? “Yeah!” And would they like to know how much money the international nonprofit raised? You betcha they would! Happily for them, they would soon know all these things and more. But before the international fundraising tally arrived via simulcast from Scientology “Flag” in Clearwater, Fla., there was the matter of honoring local donors, each of whom had made several-thousand-dollar contributions to the local org to fund expansion of their offices. All but one of the honorees were introduced as doctors.

The night’s main event began with the Birthday Game, which pitted Scientology orgs from each inhabited continent on Earth against each other in a fundraising race in the name of “religion tech.” (Someday, once the entire planet has been “cleared,” a video voice-over said, other planets will be involved, too.)

Next came highlights from the previous year: When race riots in Cincinnati last year left 87 people dead, said the simulcast’s emcee, Scientology volunteer ministers (VMs) were among the first on the scene to quell the violence (never mind that not a single person actually died in the riots). While race-fueled shootings continued across the city, in Cincinnati’s “ghetto,” where VMs distributed Scientology’s “The Way to Happiness” pamphlets, not a single act of violence was committed. And on a local radio show not much later, “a leading government official” presented “her vision of how to bring tolerance to her city.” That vision, of course, was “The Way to Happiness.”

At no other time in Scientology history, gushed the emcee — an early Don Knotts type — has L. Ron Hubbard’s message been so potent. “Just since September, that LRH way to a world of decency has been placed in the hands of 1.7 million people planetwide.”

Response to the church’s latest TV and radio appeals for volunteer ministers has been phenomenal. As of that night, the emcee added, more than 60,000 people had called their crisis hotline — an average of more than 6,000 a week.

Then there’s Narconon, Scientology’s drug treatment arm. While few media outlets relish surrendering valuable airtime to unpaid public service announcements, the emcee said Narconon’s PSAs have been so popular CNN is demanding more. In keeping with Scientology’s anti-psychiatry message, Narconon goes deeper than your average drug treatment program by battling not only the expected crack and heroin scourges, but also our society’s addiction to prescription meds.

In time, Scientology plans to expose “the big lie that emotions are just so much chemical reaction,” intoned the Don Knotts doppelgänger. In San Diego they went so far as to place ads on the sides of prescription bags urging the medicated masses to dial up Scientology’s druggie hotline — all through the narcotic appeal of their slogan, “No matter how bad it is, something can be done about it.”

“We can’t make people stop writing prescriptions,” the emcee conceded, “but we can let people know the real answer.”

Then there was last year’s big Scientology coup: the “wake-up call” in New York. Some of us may forever recall it as 9/11, but to Scientology minds it was just another reminder that the whole world could use a hefty dose of e-meter auditing. The simulcast then took followers back in time to Scientology’s previous contributions to world politics — namely their efforts in bringing down the Berlin Wall and dissolving the Soviet Union.

Four and a half hours into the high-tech birthday fete, my companion and I tried to sneak out during one of the incessant standing O’s. But the church leaders gathered outside by the bathrooms intercepted us, eager for our impressions of the evening. Too long, we concluded, half-apologizing for ducking out early. They nodded sympathetically, half-apologizing for the evening’s seeming endurance record. But it wasn’t over yet.

Asked to submit to an exit interview, we deflected their probing questions with a few of our own about the e-meter that had suddenly appeared on a nearby table. The thing was adorned with knobs and two silver cans attached by small cables, suggesting a childhood phone game.

I tried it first, grasping the canisters in my hands and bracing for the shock that would brand me a heretic. The e-meter’s operator told me to conjure the day’s most unpleasant moment (I didn’t have to reach far for that) and the machine’s needle jumped abruptly rightward. Of course the needle seemed to jump whenever anyone grabbed the canisters. Pressed to explain how the device worked, the woman said it measured the mind’s resistance to current passing between the canisters. Impossible, countered my companion, a neuroscientist by profession, adding that 50 years of neuroscience research says that can’t be measured.

Oh, but see, she explained, the e-meter’s not about the brain. It’s about the mind. Of course, the mind! we thought. Must’ve lost that when we walked in the door.