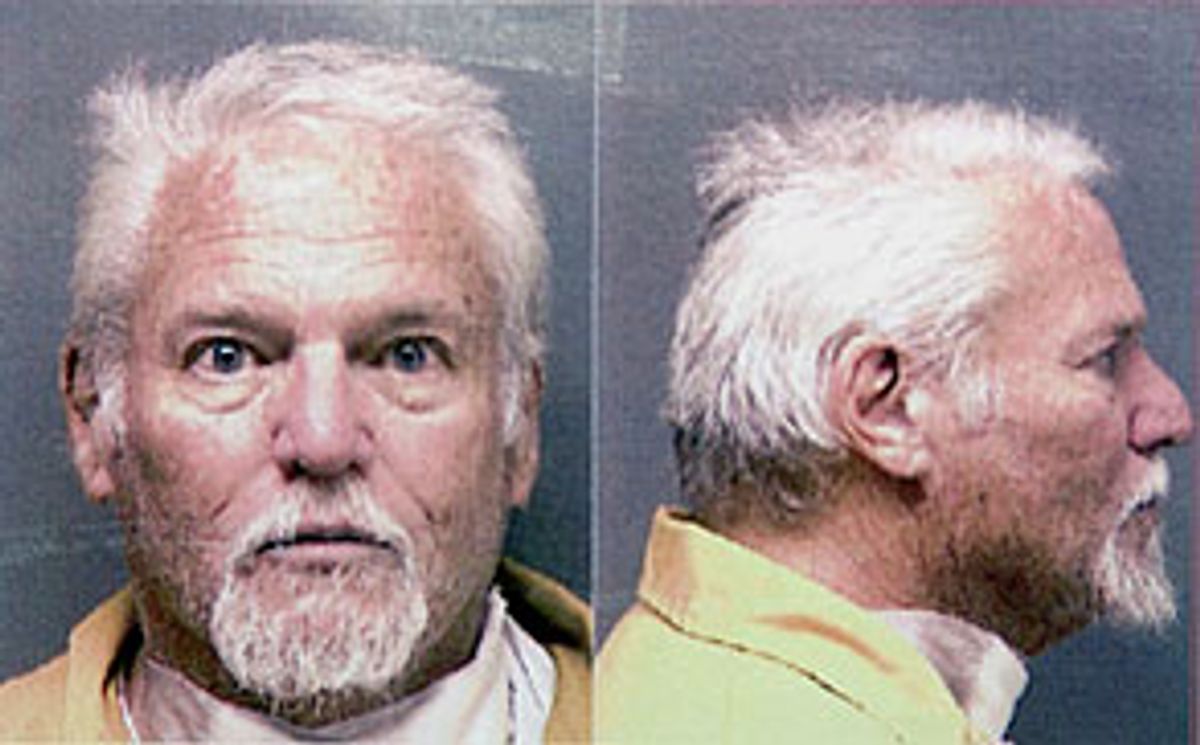

Ira Einhorn, the smart, smooth-talking icon of Philadelphia's counterculture in the late 1960s and early 1970s, finally got the murder trial he wanted: one with no death penalty. On Thursday, he got the sentence that relatives of his victim, former girlfriend Helen Holly Maddux, have sought for over 20 years: life in prison without the possibility of parole.

For four weeks, a racially mixed jury of six women and six men (and a packed courtroom filled with curious spectators) heard both sides of a case that began with the 1977 slaying of Maddux, a pretty young hippie who was found a year later mummified in a crate in Einhorn's closet. They heard the prosecution's evidence that it was all Einhorn's doing, and they heard Einhorn's claim that he had been framed by unidentified "enemies," possibly the CIA or KGB.

The jury went with the prosecutor.

The 62-year-old Einhorn, who spent 20 years on the lam after skipping out on his 1981 trial while free on bail, stood stoically as the jury foreman read out the verdict: guilty of first-degree murder. But he shook his head slowly in a sign of disagreement as the judge, William Mazzola, read out the sentence -- life in prison without parole -- and told Einhorn he was "an intellectual dilettante" who "preyed upon the uninitiated, uninformed, unsuspecting and inexperienced."

It was a hard fall for a man who a few decades earlier had been the toast of the town, courted by the trendy elite of Philadelphia. It was also the end of a long manhunt by Maddux's family, who hired a private investigator to track the elusive suspect down; when finally located, Einhorn was living the life of an expat gentleman, complete with Swedish wife, in rural France under the name Eugene Mallon. But France came to see his case as a human rights cause célèbre, with prominent attorneys and others arguing that he'd been unfairly tried in absentia and so should not be extradited. It took several years, a special law passed by the Pennsylvania Legislature and a promise by the Philadelphia district attorney not to seek the death penalty to win his extradition -- and if the law is found unconstitutional, it could be his ticket to a successful appeal.

Einhorn, who took the stand himself, came across as a profoundly egocentric and libidinous character with a history of battering girlfriends who wanted to leave him. In the end, the University of Pennsylvania English grad was hoist on his own literary petard. A diligent diarist, he was led during cross-examination by Philadelphia Assistant District Attorney Joel Rosen to read from extensive portions of those diaries.

One entry, written after an evening with a girlfriend, Rita Resnick, who was in the process of dumping him, read as follows: "To kill what you love seems so natural that strangling Rita last night seems so right." Resnick had testified about the strangling incident, which occurred in 1965, earlier in the trial.

Einhorn, who rarely appeared agitated, read this and other damaging diary entries in a mellifluous voice, addressing the jurors directly, with the air of a patient university professor. He tried to explain the brutal statements away as "metaphorical" or "literary" musings.

Conceding that he had had problems with uncontrolled violence in his relationships with women during the 1960s, Einhorn claimed that he had gone to the proto-New Age Esalen Institute in California for treatment and that by the time he was with Maddux, he had been cured. That claim was undermined, however, by a number of witnesses who testified to having seen her covered with bruises.

Throughout the trial, the prosecution assembled an enormous body of circumstantial evidence against Einhorn. There was the rotted and mummified corpse found inside a steamer trunk in a locked closet in his apartment. There was a report of a fight in Einhorn's apartment around the time Maddux went missing, which included a terrified scream and a series of loud bangs on the floor. Then too, there was testimony of a stinking, reddish-brown fluid that for weeks was dripping through the ceiling into a downstairs apartment closet directly below the one where Einhorn kept the steamer chest. And there was testimony that Einhorn had put multiple locks on the closet and vehemently denied requests by the landlord for access to that closet.

Einhorn's defense attorney, William Cannon, countered by noting that his client had been absent from the apartment for several months in early 1978. During that time, Cannon suggested, several other people had had access to the space and could have sneaked the body in so as to frame his client.

The problem with that scenario, as prosecutor Rosen pointed out in his closing argument, was that Maddux's mummified body exactly fit the steamer trunk, and could not have been adjusted to fit the box without the papery skin tearing. Furthermore, photos of the trunk showed a moldy interior, delamination and heavy staining of the trunk, carpet and flooring underneath the trunk -- all proving that the body had, in fact, decomposed inside the trunk.

Einhorn never denied that the trunk was his. But he claimed that it had contained piles of papers -- secret reports about KGB and CIA mind-control experiments.

Perhaps Einhorn's strongest argument was that he had not destroyed his extremely damaging diaries. His defense attorney had him read a series of entries from the days immediately following Maddux's Sept. 11, 1977, disappearance. Those entries referred to his anguish at her leaving, and to his efforts to locate her. Prosecutor Rosen, who also tried the in-absentia case in 1993, argued that Einhorn had made an elaborate effort to develop an alibi in his diary.

Einhorn's case was seriously undermined at the end of the trial when the prosecution brought in one last rebuttal witness, a psychiatrist named Donald Nathanson. Einhorn, during his testimony the day before, had spoken at length about his '60s-era protest activities in an effort to make the case that powerful interests may have had an interest in setting him up on a murder rap. One of his claims was that he had been the organizer of the 1970 Earth Day protest, and in fact had been the event's MC in Philadelphia.

But Nathanson, who said he had been on the organizing committee for Earth Day, testified that the committee had barred Einhorn from their discussions, considering him a nuisance. There was no MC, Nathanson said, and Einhorn's only role at the event had been as a liaison with poet and featured speaker Allen Ginsberg. But, Nathanson said, Einhorn didn't merely introduce Ginsberg -- he "commandeered the stage," speaking "incoherently" for half an hour and refusing repeated requests to leave and let the program continue. It was devastating testimony, and the defense offered no evidence to counter it.

In one sense, Einhorn can count the verdict as a victory. He faced the death penalty when he was charged and put on trial in 1981, but he skipped the country while out on bail. Philadelphia D.A. Lynn Abraham ultimately succeeded in having him tried in absentia in 1993. At that second trial -- a first in modern Pennsylvania history and a rarity in the U.S. -- he was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Maddux's siblings, who sat through the entire trial, welcomed the outcome -- even preferring it to execution. "You know that life without parole is a terrible punishment, worse than being executed," said the victim's younger brother, John. "We want him in an environment where every day will be longer than the previous one, and where he'll know that he'll never leave but feet-first. And we hope he lives another 30 years."

Defense attorney Cannon had tried to convince the jury that there was a reasonable doubt about whether Einhorn had committed the murder. But after just two and one-half hours of deliberation -- not much longer than the jury at the 1993 trial in absentia, which deliberated for two hours -- the jury came back with their guilty verdict. They rejected an alternate third-degree murder charge.

A few minutes later, after polling the jury, Mazzola pronounced the sentence of life without parole. He said he had no discretion under the law, but added that if he did, he would have imposed the same sentence himself.

Einhorn can now appeal his conviction in state and federal court, but his best chance to overturn the conviction may be to challenge the legality of his trial, which was indeed unprecedented. At the time of his arrest in France, Pennsylvania law had no provision for retrying a case that had already been tried in absentia. In order to gain French approval for extradition, the Philadelphia D.A. had to get the Pennsylvania state legislature to pass a special law authorizing a second trial. This so-called Einhorn Law could well be declared unconstitutional.

That would leave Einhorn convicted and sentenced to life under the 1993 in-absentia verdict, but some experts believe it might then be easier to appeal that verdict because it was handed down when the suspect was not there.

Shares