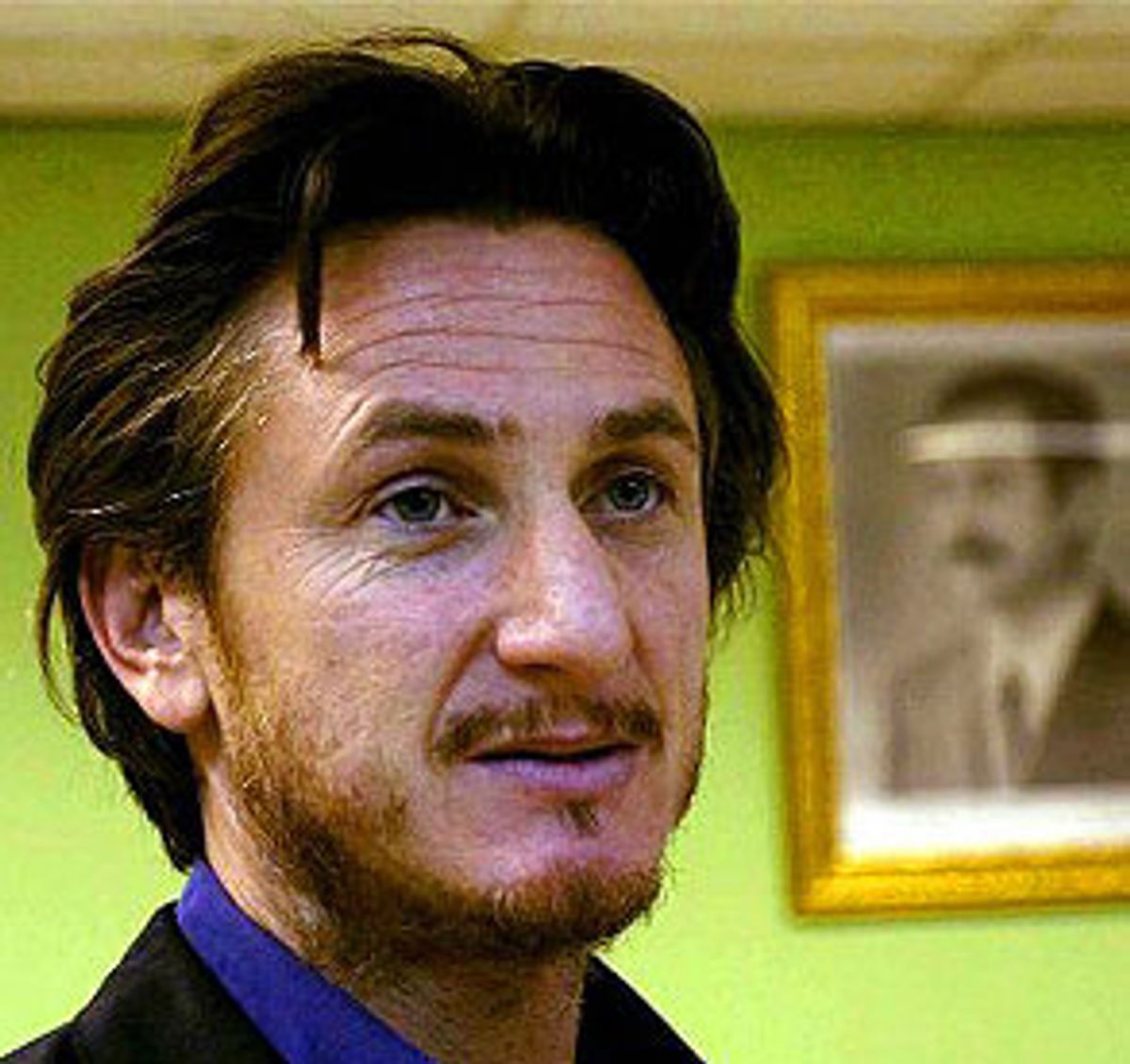

One of the first questions Larry King asked Sean Penn Saturday when the actor appeared on his CNN show was why anyone should listen to his opinions about a possible U.S. war with Iraq. Penn, after all, has no discernible foreign policy expertise, as conservatives have trumpeted in fusillades of anti-Penn mockery. The brooding ex-husband of Madonna, the man who brought us Jeff Spicoli, doesn't think, after a three-day visit to Baghdad, that George Bush has made the case that America should invade Iraq. So what?

"I'm not here as an actor. I'm here as a citizen," Penn said. To which King replied, "A citizen wouldn't have been on this show."

But that, activists and actors on the left contend, is exactly the point. At a time when the voices against a war with Iraq that are getting the most attention are those of Penn, Martin Scorsese and Janeane Garofalo, many Bush critics are ceding that the best way to get on the air any dissent against what increasingly seems like an inevitable war might be through celebrities.

King's own show is a good example: In the week before Penn's appearance -- a week in which chief U.N. weapons inspector Hans Blix announced his teams had found "no smoking gun" in Iraq and North Korea's Kim Jong Il ratcheted up his crazy game of atomic chicken -- his guests included "famed spiritual medium" James Van Praagh, low-carb diet guru Dr. Robert Atkins, James Hewitt (Princess Diana's former lover), Jermaine Jackson, and Brenda van Dam, whose 7-year-old daughter was murdered by her pedophile neighbor.

Garofalo told Salon that she felt the need to speak out publicly because the people who were already speaking out don't get the audience they deserve. "I wish all the time I was booked on those news programs that they had booked Howard Zinn or members of Veterans for Common Sense," she says. "But of course they choose to book myself and a handful of other actors so they can force us to spend the majority of our time on the news defending why anyone should listen to us."

Progressive Hollywood stalwarts such as Susan Sarandon and Martin Sheen have been out front on the issue almost from the start, but it's just in the last month that the rest of the movie industry has become noticeably organized. On Dec. 10, producer/director Robert Greenwald and actor Mike Farrell held a press conference to announce the formation of Artists United to Win Without War, a group of 100 celebrities including Matt Damon, Samuel L. Jackson and Helen Hunt who signed a statement saying, "We reject the doctrine -- a reversal of long-held American tradition -- that our country, alone, has the right to launch first-strike attacks." On Jan. 9, Martin Scorsese came out against invading Iraq. On Monday, Garofalo is co-hosting a talk by weapons inspector-turned-critic Scott Ritter in Manhattan, after already speaking about her opposition to the war on ABC's "Good Morning America," and on Fox, CNN, MSNBC and several radio talk shows.

"At our press conference, we had 15 television cameras, maybe seven, eight or nine radio stations and 25 reporters," says Greenwald, who produced "Unprecedented: The 2000 Presidential Election" and directed the 2000 Abbie Hoffman biopic "Steal This Movie." "As I said to one of the reporters, if we had a hundred Nobel Peace Prize winners, we wouldn't get one quarter of this attention. Everyone who signed on knew it was an easy, cheap bite for a media obsessed with celebrity, a media that has completely given up its responsibility and desire to present complex alternate points of view."

Actors, Greenwald says, have "the power to get other ideas into the culture, into the mainstream." To that end, he and Farrell are organizing other groups of antiwar entertainers to reach specific demographics. "We're working to create Young Artists United to Win Without War, with young actors like Jake and Maggie Gyllenhaal and Kirsten Dunst. Probably in late January we'll be doing some kind of substantive announcement about that. We're also just beginning to undertake Soap Operas United to Win Without War to get out to the middle of the country."

Soap opera stars against war? It sounds absurd, but those involved don't see any other way to get their message out to the people who need to hear it.

"People are afraid of being labeled unpatriotic, because our government now is starting to operate more like a police state than a democracy," says former "Baywatch" star Alexandra Paul, speaking on her cellphone above the sounds of an antiwar demonstration in Los Angeles. "The L.A. Times here in Los Angeles does not cover the antiwar movement at all. It's despicable. In this day and age the media has become so conservative that they do not state the truth about what's going on in America. It seems like there are no dissenting voices, but there are. People think they're alone because they don't hear other voices in the media."

Most polls suggest that a solid third of the country remains unconvinced that the United States should invade Iraq; a Jan. 4-6 CBS News poll said 30 percent disapproved of military action against Saddam Hussein, compared with 64 percent that approved of it. And even those willing to back Bush aren't itching for an invasion -- 63 percent (as opposed to 29) felt that a diplomatic solution should still be pursued, suggesting that, as antiwar advocates contend, a large segment of the population remains unconvinced that a war is necessary.

Still, are celebrities really the best way to reach out to that public? Garofalo acknowledges that when actors become spokespeople, it "turns into a double-edged sword, because actors are used as a means to marginalize the movement." Penn said much the same thing to Larry King, noting that when actors join a cause, it can "give it an air of buffoonery."

"If you're an actor who is against the war, you're seen as somewhat of a crackpot," Garofalo says. "If you're an actor who is pro-war, you're a hero." Penn put it even better, telling King, "Opponents of actors speaking out generally voted for Ronald Reagan."

Yet even if antiwar celebrities are reviled by the right, some activists on the left believe that they've already helped chip away at the taboos against criticizing Bush after 9/11. "I think recent statements from a lot of actors and other entertainers have helped to disrupt a prevalent mood of quasi-conformity," says Norman Solomon, the San Francisco lefty media critic who arranged Penn's visit to Iraq. "I'm not at all a fan of celebrity culture. But this is an emergency situation.

"I think there's a mood among people, including quite a few celebrities, that we're not going to be quiet this time," Solomon says. "Not this time. We're not going to watch this horrific war extravaganza unfold and simply take it in. We're going to express our deep concerns ahead of time and not just participate in the postmortems."

Of course, Hollywood has participated in lefty politics (and at times, been punished for it) almost since its inception -- Penn's father, director Leo Penn, was blacklisted during the McCarthy era. Yet never before has the media looked to Hollywood as virtually the only spokespeople for a specific cause.

Jane Fonda was certainly visible in the movement to stop the Vietnam War -- and the specter of "Hanoi Jane" surely haunts some celebrities wary of the potential backlash. Fonda, though, wasn't the face of the era's protest -- it generated its own stars, from Abbie Hoffman to George McGovern.

"In the '60s, people were looking for answers, and there were new spokesmen popping up all the time," says Leo Braudy, a University of Southern California English professor and the author of "The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and Its History." "Now the media is much more about familiar faces and market share." Thus Garofalo gets more attention for her antiwar stance than Archbishop Desmond Tutu, a Nobel Peace Prize Winner, does for his.

That means smaller movements rely on celebrities to sell their cause. "What celebrities can do is flag things, the same way they do with advertising. Then consumers make their choices," says Braudy.

John Orman, a political science professor at Fairfield University and co-author of the book "Celebrity Politics," points out, "In 1985, we had the farm crisis in the Midwest, and the first three witnesses called to testify at congressional hearings were Jessica Lange, Sally Field and Sissy Spacek, because they had recently portrayed poor farm women. The next day real poor farm women came in and nobody showed up."

Still, even if she's invited on television only because she's in the movies, Garofalo comes prepared and can hold her own. On Dec. 10, as Fox's Bill O'Reilly ranted that Bush is protecting Americans and that Saddam needed to go because he threatens Israel, Garofalo said, "We want to see Americans protected. We do not believe that a military strike in Iraq makes Americans more safe. And it also escalates the violence consuming Israel and Palestine." Later, she nailed her bellicose host when he tried to insist there was no secret U.S. bombing campaign in Cambodia.

"It's a drag to have to defend yourself and your profession and the entire antiwar movement," she says. "I'd rather a more qualified person do it. Having said that, I'm constantly immersing myself in the subject. I don't come to any of these news programs lightly. It's a huge responsibility and I respect that."

Penn, too, brought a note of thoughtful skepticism onto CNN. Unlike Garofalo, he's not terribly well-spoken and has a tendency to mumble, but his words were judiciously chosen. While not arguing against war under any circumstances, he insisted on the inadequacy of the administration's case for invasion and implored the audience to consider the human cost of combat.

He urged viewers to take out a pad of paper and write, "'Dear Mr. And Mrs. So-and-so, we regret to inform you that your son has died in combat.' Then you have to finish the letter in a way you can feel comfortable with. If you can do that, you have one side of the debate and I respect that ... But if we go to war without having examined those things, we're left with the question of what kind of country have we protected."

Shares