There are two almost unbearably painful moments in Taran Davies' documentary "Afghan Stories." One assumes that a documentary about that tragic country, filmed while it was still in the death grip of the Taliban just weeks before the post-Sept. 11 American bombing campaign, would include a handful of heart-wrenching scenes. But these two stick out. In the first, a very young Afghan boy, sequestered with his large family in a small, spare Tajikistan apartment where they've fled the Taliban in hopes of someday reaching family members in Canada, sits in his mother's lap. At her urging, he sings in a tiny, predictably angelic voice, a song, or an anthem, for their lost Afghanistan.

The next scene is almost more important: At the end of the film, Davies replays the tape for the child's relatives in Canada. And Davies' story of ordinary Afghans -- some displaced, some enjoying new lives in a Western world about to wage war on their brothers -- comes full circle. The boy, himself living in exile, is singing to his Afghan grandmother about yearning for Afghanistan, while she sits crying in the modern comforts of a Western living room.

After all, as Davies explained to Salon, while he wanted to help Westerners understand the Afghans, "Afghan Stories" is also about the different ways citizens deal with a shattered homeland. The film, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival and opened in New York last week (you can catch it on the Sundance Channel on May 19 at 10 p.m.), is one of the few documentaries to emerge about Afghanistan since Sept. 11.

Davies, a former New York investment banker and part-time filmmaker (his other film, about the Chechen conflict, is called "Mountain Men and Holy Wars," also on the Sundance Channel, May 19, 9 p.m.), had a distinct advantage: A friend of a friend named Walied Osman, an Afghan-American entrepreneur, volunteered to accompany Davies on his trip. In the beginning of the film, Osman relates his sister's reaction to the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks. Immediately, she said, Afghanistan should be bombed.

Osman's story is a reassuring indication that Davies will ably convey the complicated feelings that Afghans have about their country and the West. What Davies and Osman found might have been a broken country, but the Afghans they interviewed, fully knowing that bombs would fall on their homes in days, had hope for the future. In the film, Davies spends a great deal of time with Ad Sharza, a charismatic and surprisingly cheerful Afghan man who now lives in Queens, N.Y. In Afghanistan, Davies and Osman lived for a while with Ahmad Shamsadin, an esteemed Islamic cleric -- without ever meeting any of the female members of his household.

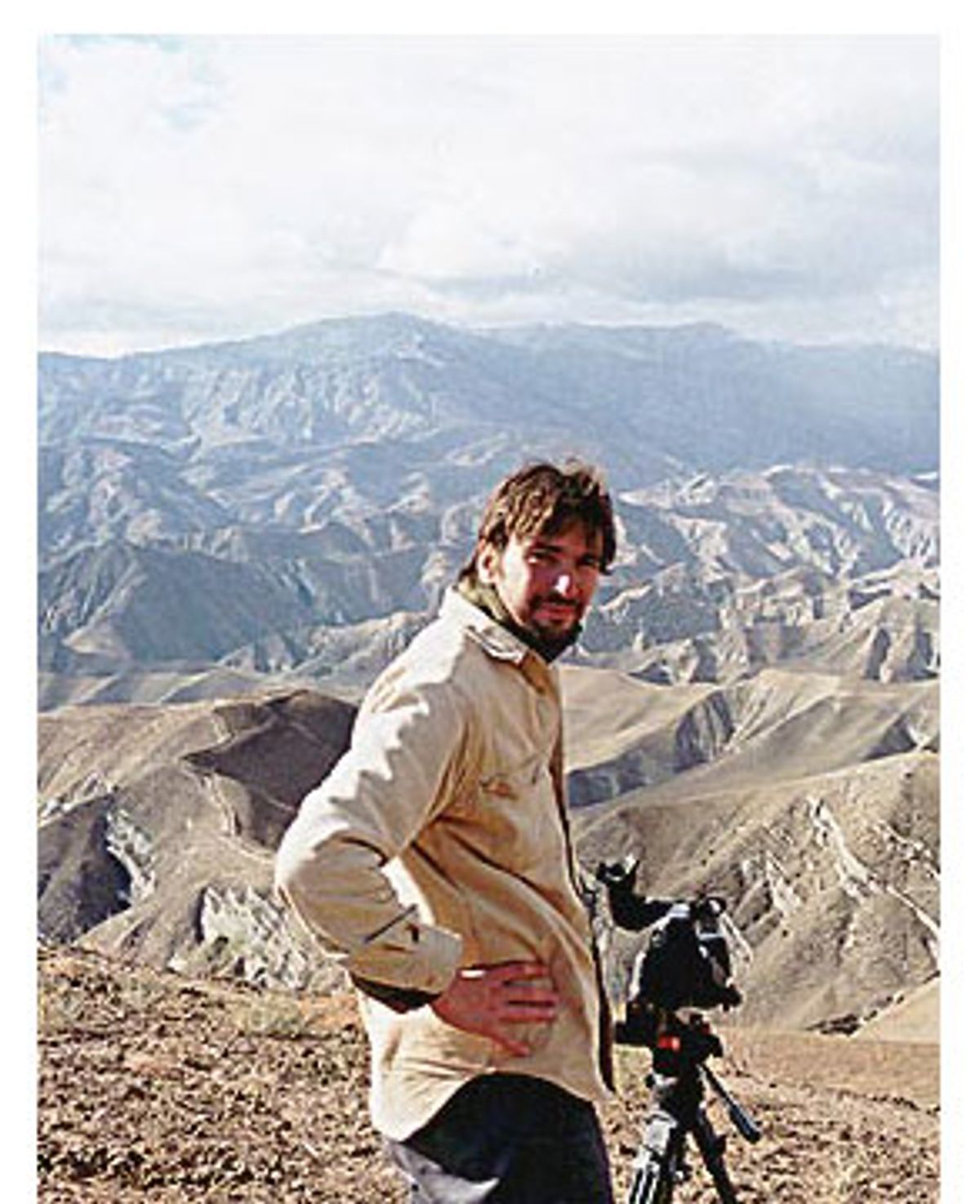

Salon spoke to Davies, now 32, about warlords, reporters hungry for war footage, and the Afghans' expectations of their new relationship with the West.

You were a banker. Why did you decide to make "Afghan Stories"?

My office was just a couple of blocks away from the World Trade Center and I live in TriBeCa, so I witnessed everything. Like everyone else I was moved to help in some way, as much for myself as anyone else. Because I had traveled so extensively and made films in that part of the world, I felt like Afghanistan was a place I could get to easily. We sensed that the U.S. was about to bomb Afghanistan and I thought I could bring some understanding to that. In the U.S. we had very little sense of who the Afghans were. When I left for Afghanistan, there was only one film being shown on CNN, "Beneath the Veil," which served a great purpose but, I felt, didn't give us a sense of who the ordinary Afghans were, the ones who weren't terrorists or refugees, the ones leading quasi-normal lives. These were the people we were going to bomb, too.

Was Walied Osman, the Afghan-American who accompanied you on your trip, a friend?

He was a friend of my girlfriend. When I told him my idea, he immediately said he wanted to come. We met 10 days after Sept. 11 and we left Oct. 15. In about two weeks, we went from our meeting to having arranged everything we needed to do to get into Afghanistan -- including [dealing with] the moment when one tells one's parents.

What did your parents say?

My mother rang my girlfriend up and said, "Natalie, under any other circumstances, I would never ask anything like this. But just tell Taran that you're pregnant."

Can you give a sense of how dangerous a trip this was? What were other Afghan-Americans telling you?

Everyone's counsel was not to go. That was why we went to meet Ad Sharza, Walied's family friend. I wanted to go live with Afghan families and tell their stories. As Sharza said to us, at any time this would be impossible, let alone at a time of war, because two young men staying with Afghan women is impossible. And he was right. When we were living with the Islamic elder Ahmed Shamsadin, we never once in the weeks that we stayed with him saw his female relatives.

Can you talk a little bit about Sharza?

Sharza had traveled back to Afghanistan at the invitation of the Rabbani government to help rebuild the Afghan airline. That government was captured by the Taliban and Sharza had to go to jail.

He said one of the most shocking things in the film -- that someone should just drop a bomb on Afghanistan and obliterate it. What did you make of that?

Sharza is more patriotic than anyone else I met. He loves his country unquestionably, so his comment shouldn't be taken too literally. He was suggesting that Afghanistan had become reduced to nothing over the past 24 years. It had been beaten down to nothingness. It's a country that could no longer see into the future or remember their past. He is an extraordinary character, a really good man. At the bottom of his heart all he wants is the restoration of his country.

Does he want to return?

I think he longs for it desperately.

What about Walied? What about the Afghans in Afghanistan? Did they want their people around the world to return?

When we were in Afghanistan, Shamsadin made the plea that we deliver this message to the Afghan diaspora in the West and in the U.S.: "We have not forgotten about you, don't forget about us. Come back and help rebuild your country." We returned to the U.S. with great excitement to deliver that message, and what we encountered was reality. Which was that, as much as the members of the Afghan community in the West want to return, the actual realities of doing so are maybe too difficult to overcome -- their children have grown up here in the West, there's less security and less income in Afghanistan now. Fewer have gone back than were expected; nevertheless many people have gone. Walied hasn't returned, but his sister and mother did.

When you were there, were people in Afghanistan looking forward, beyond the bombing? Did they have expectations for the future?

They were all looking beyond the bombing. Everyone had a vision of what would happen. They had a vision that bombing would oust the Taliban and that a loya jirga [a tribal council unique to Afghan culture, in which elders come together to make decisions] would come to power. Their dream has come true in large part. To say that they expected the Afghans in the West to return -- I don't know. What I do know is that Ali Baig, the man in Tajikistan ... Let me ask you, would you go back? You heard Ali's story, would you want to go?

I understand what you're saying -- the conditions under the Taliban were horrific and that family endured so much tragedy. But I figure that it depends. Some people always want to go home.

What I think is interesting about "Afghan Stories" is it applies this story of the relation to one's homeland from all different perspectives. We first visit Sharza, who fled many years ago, went back to help and got screwed. You have Ali Baig, who stuck it out for so many years and now would do anything to get out. There's Shamsadin -- he has stuck it through and will die in Afghanistan. Then you have Najib Najibullah, who actually chose to stay to help his people. He also has the best job you could ask for -- the head of the World Food Programme -- but this is a man who lost his brother to the Taliban. He loves his country so much he has stayed.

I wanted to ask you about one story related in the film. Someone said that he'd seen reporters paying the Northern Alliance to fire on the Taliban. Is that true?

We met a Canadian journalist who said the worst thing he'd seen was Western television reporters paying the Northern Alliance to fire on the Taliban and then the Taliban firing back. I'm not saying that that actually happened -- he is.

What was the worst thing that happened to you, the most uncomfortable situation or the saddest?

I'd love to be able to give you one, but ... It's interesting to go into a country that you're bombing and not take the path of the journalist, but go and live with members of the Afghan community and feel safe and expect to be welcomed. What can I say? We were received with open arms. "Serendipity" would be the key word. I couldn't have done this without Walied -- he was the only Afghan-American on the ground at the time that we ever encountered or heard of. Because I was traveling with him, we were able to go places that others weren't.

Did either of you have any political agenda?

Part of what motivated this film was the question of what people think of what happened in the U.S. [the 9/11 attacks] and what they think of the U.S. bombing Afghanistan. I learned that in Afghanistan these people were more moderate in views -- whether it was Islamic leaders or refugees. When it came to matters of religion and politics, they were more middle of the road than you find here.

Did they want the U.S. to bomb their country?

They hated the loss of life, but they felt that there was a price that needed to be paid for their freedom.

What was your impression of the women?

The really exciting thing for us was that we began in Tajikistan with an Afghan family. There we had access to women and lived with them in their apartment for a week. That was rare and unique.

Completely. It seemed all quite normal. It wasn't until I got to Afghanistan and saw everyone covered ... Shamsadin is such an extraordinary man and I'm afraid my film doesn't do him justice. This is an Islamic elder [not a member of the Taliban regime, but a leader of his town of Faizabad] and he was one of the first to unveil his wife. He himself is horrified by the veil, but, as he says, it's for women's protection because there is no law.

The towns are run by factions of warlords; they're the ones with the guns. It's one thing in Kabul for the women to unveil themselves, but it's another thing in the country where it's more religious. Shamsadin's son talked about it as a tradition: "If you come to a country of one-eyed people, you must blind one of your eyes." In other words, if this is what the law is, this is how it must be.

What were your encounters like with the warlords?

The head of the World Food Programme has a relationship of sorts with this warlord. There's a scene where we're trying to leave the warlord and he's asking us to stay. We have to negotiate to return to Faizabad after having tried to get to the end of the road. The warlord asks us to stay for tea and we say no, but he insists. There's something threatening about it, but it's really a matter of protocol. You do show your host respect. We learned that it's the reality of the situation on the ground -- the warlords control much of Afghanistan and they always have. These are the people who we have to work with to get things done. The effort to change that could take centuries.

Shares