Every now and then I feel the fear and start to fret that video games will be the death of culture. I read news articles reporting that fewer boys are playing Little League baseball because they'd rather be playing with their GameBoy Advances. I finish a seven-hour session of some role-playing game, my brain fried and wrists aching, and wonder what will happen to my kids, for whom the games will be even more immersive and compelling. I panic at the thought of a future in which everyone spends all their time stoking their fantasies in virtual worlds, at the expense of reading books, or listening to music, or being creative in any productive fashion.

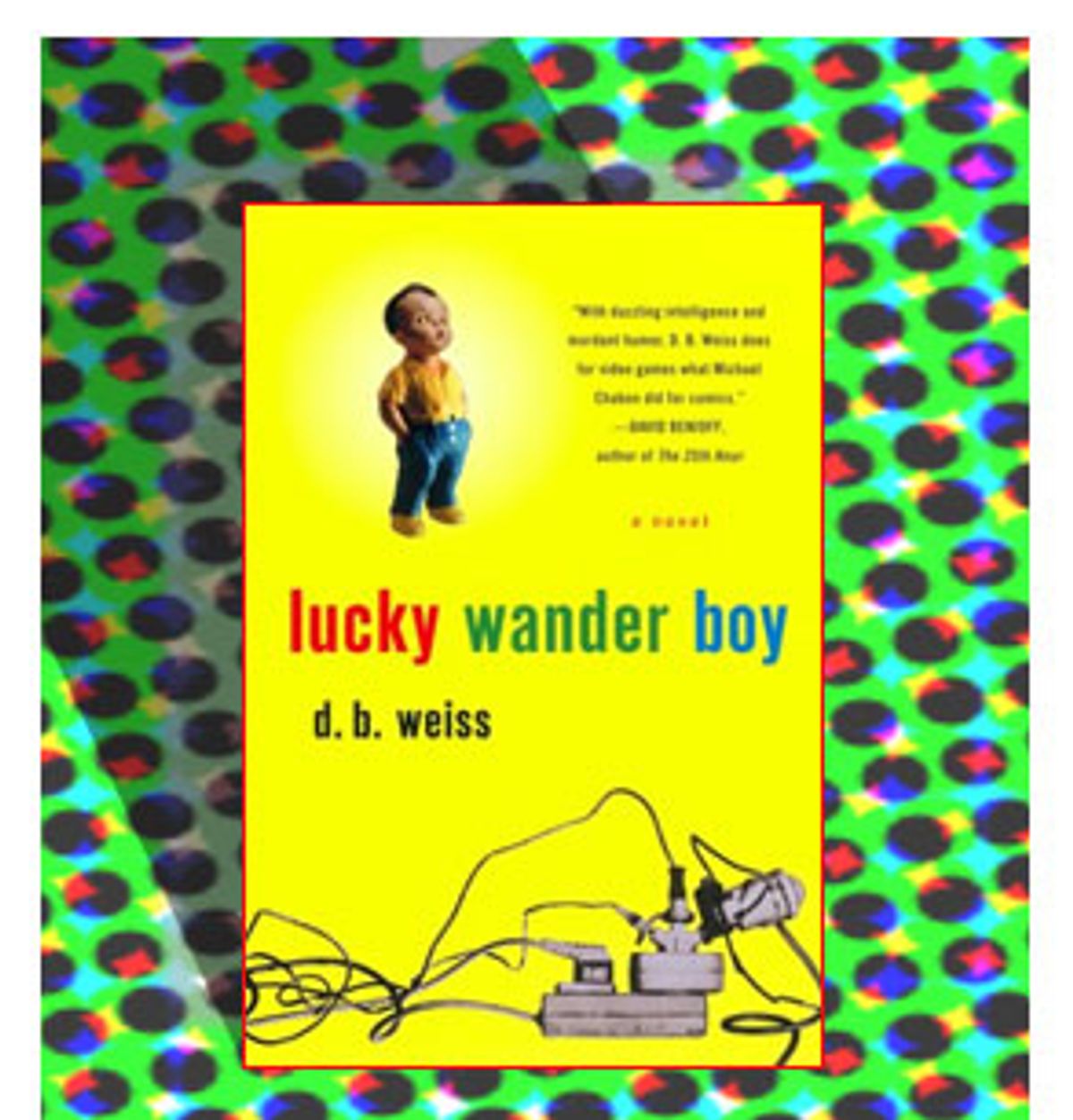

And then I read a smart, engaging novel like D.B. Weiss' "Lucky Wander Boy" and I take a deep breath and relax. No matter what methods of distractions we humans devise for ourselves, we will always be able to turn the tables and make art out of our addictions. Enduring truths lurk behind every pixel, and profound meanings are signified by Pac-Man's maw. A generation reared on video games will produce some zombies, sure, but it will also engender poets -- bards of a new digital discipline. Weiss is just such a bard, making merry with the grist of "Donkey Kong" and "Frogger," capturing the spirit of a generation raised on arcades and Atari cartridges.

A back-cover blurb on "Lucky Wander Boy" declares that Weiss does for video games what Michael Chabon did for comic books in "The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay." That's high praise, and more than a little hyperbolic, but not without some merit. Both authors take low culture and treat it with high regard.

As befitting a lad reared in the surreal absurdities of the classic age of video games, Weiss also treats his subject matter with ironic disregard, which gives his narrative a nicely subversive twist. "Lucky Wander Boy's" protagonist, Adam Pennyman, spends his spare time working on a "Catalogue of Obsolete Entertainments" in which he eulogizes and deconstructs the games of his past as if he were some bastard crossbreed of Proust and Derrida. He's serious, but he's also ludicrous.

The result is a delight. When Pennyman invokes Hegel or Marx in the same breath as Pac-Man, you sense the author is having purposeful fun, mocking both the games and his own protagonist. It's just plain silly to argue that Pac-Man's "insatiable hunger" reminds us of "Marx's 'need of a constantly expanding market' that 'chases the bourgeoisie over the entire surface of the globe.'" In fact, it's the kind of profound observation that could only be generated by someone who had spent far too much of his life wrapped around a joystick.

Furthermore, I'd venture to bet that the number of "Pac-Man" players who were ever reminded of Marx as they plunked their quarters into arcade machines is vanishingly small. But the juxtaposition is still fun, and the notion of a character who would dive so deep into the morass of his obsession that he could generate a whole pop-cultural critique easily rings true. Who cares if that critique has no validity outside the crazed brain of Pennyman?

There is a plot in "Lucky Wander Boy" -- Pennyman's search for the mysterious Japanese game of the same title provides a motive force for the novel. The book also takes aim at dot-com era shenanigans: Pennyman, a feckless layabout who is good at games but not much else, ends up working as a Web site copywriter for a Hollywood dot-com that makes schlock movies, many of which are based on video games.

But the plot is window dressing for Weiss' long-distance journey into the heart of video gaming. Pennyman isn't just a young man who thinks too much about the deeper meaning of video games; he's a product of a life spent gaming. He slithers in and out of jobs and relationships and passions as if he were rolling his mouse through an on-screen world where consequences don't really matter, because you can always start over, provided you have another quarter.

Similarly, the novel isn't just about a man whose formative experiences came while trying to get a digital frog safely across a highway. Structurally, it's a literary representation of a game itself -- right down to the point where several crucial scenes are "replayed" to produce different outcomes.

Death is never final in an arcade. But what does that mean for a generation raised with such virtual powers? Do grown-up gamers believe, deep in their subconscious, that they get unlimited extra chances? Does this prevent them from truly engaging with the harsh edges of reality? Do the alternative endings that blossom at the end of "Lucky Wander Boy" give the author an excuse for not nailing down a conclusion?

A novel about gaming lends itself to adventurous literary techniques that would seem forced, or too self-consciously postmodern, in other contexts. But those various techniques can also create an atmosphere of superficiality -- more flashy distractions for an attention deficit disordered generation. But isn't that, in turn, utterly appropriate for a novel exploring a kingdom ruled by Donkey Kong?

Forget about poor Adam Pennyman and his existential plight. The larger truth of "Lucky Wander Boy" is that anything we do as humans, no matter how apparently evanescent, creates a substrate for our lives that is worth examining. Maybe it's true, as Pennyman observes in a moment of self-doubt at his own analysis, that his metaphorical flights of fancy are too "suspiciously obvious" and that "these kinds of interpretations belie the poverty of imagination that has become all too typical of practitioners of the interpretive arts."

But that just sets up the real challenge. We're human, and increasing numbers of us are spending increasing numbers of hours playing video games. It's got to mean something.

"If Pac-Man and the games that followed in its wake mean anything to us," observes Pennyman, "if they are central switching stations through which thousands of our most important memories are routed, it is our duty to dig deeper."

Think about that the next time you are playing "Solitaire" or "The Sims." There may be a novel, or at least a Ph.D. thesis, waiting to be born.

Shares