Inside Room 175 of the Contra Costa County courthouse, 20 miles east of San Francisco, men and women in yellow jumpsuits press themselves up to the barred windows of a Plexiglas-enclosed jury box that holds in-custody defendants. They are straining to hear drug counselors describe a new twist in the justice system, a change that to some must sound like a dream -- or a trick. Since when is compassion the punishment for drug crimes?

In California, since November 2000, when voters passed the Substance Abuse and Crime Prevention Act, or Proposition 36. Under Prop. 36, people convicted of drug possession are automatically steered to rehab rather than to jail. They still report to a probation officer, and the stick of incarceration hovers over their heads should they rack up three "treatment failures." But the state has effectively shifted its philosophy for dealing with drug offenders, replacing a harshly punitive response with an offer of recovery.

When Prop. 36 became law, it looked like an anomaly in a nation that had recently surpassed Russia as the world's most prolific jailer. But that was before the economy tanked, tax revenues plummeted, and state governments were confronted with the worst budget crisis since World War II. Today -- after two decades of overheated anti-drug rhetoric and skyrocketing prison populations -- prison spending is losing its sacred-cow status, and compromises like Prop. 36 are gaining appeal.

The California measure is still considered an experiment, one that breaks down and even fails from time to time. Cases of ineffective treatment, tangled bureaucracy, and scamming by users in the program have tainted glowing reviews, but so far, the results are encouraging enough: More drug users are getting clean than under the old regime; the population of drug users behind bars for possession is diminishing (by 30 percent in 2001); the state is saving money ($95 million in the first year); and thousands of children are being spared the trauma of parental incarceration.

Can a shotgun marriage between drug treatment and criminal justice become a lasting union? The question is likely to be answered in California. And if the answer is yes, a setting like the Contra Costa County courthouse may represent the next front in a kinder, gentler war on drugs.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

A low-level criminal courtroom is often a place of tension and sorrow. The atmosphere in this room is, incongruously, one of relief and quiet competence: "We'll get this taken care of" is a frequent refrain. Defendants here have already pleaded guilty to drug possession. Probationers on the courtroom benches are back in court for a periodic "treatment review."

"Maybe it wasn't entirely your fault," Judge Douglas Cunningham suggests to a wizened, white-haired and faintly trembling man in his 60s who has failed repeatedly to make his way to treatment. A prosecutor refers to another defendant's dirty drug test as a "speed bump" and suggests he be given another chance. A warrant is issued here and there for those who have failed to show up in court, but that is the exception and clearly not the desired outcome: In this room, putting people behind bars is not the goal.

Vallee Sunnen, a counselor, steps to the back of the courtroom to do an intake interview with a tired-looking blond woman in her 30s huddled inside a long black leather coat. "How many children do you have? Are you pregnant? Employed? Homeless?" These questions are intended to help Sunnen determine what kind of treatment the woman needs, but before Sunnen can get through them, her new client angrily interrupts her. She'd rather spend 30 days in jail and be done with it, she says, than waste her time in treatment.

Sunnen gently suggests that the woman look at the big picture and pick the option that might help her quit drugs.

"I can get clean and sober anytime I want," the woman responds. "That's easy."

"Is it?" asks Sunnen. "You're here."

"Thirty days'll clean me up."

"For those 30 days."

"I'm leaving," the woman announces, and she strides out of the courtroom.

"She's afraid," says Sunnen, who is, like many other treatment professionals, herself a recovering addict. "Getting clean is the scariest thing.

"She'll be back," Sunnen predicts, and she is right. Twenty minutes later the woman is sitting quietly against the back wall, clutching her paperwork to her chest, her eyes fixed on the Great Seal of the state of California over Judge Cunningham's head as she waits to be told how the court sees fit to heal her.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

There are two dominant views on drug addiction and how it should be handled: The first is that addiction is a disease like any other and should be tackled through treatment and prevention. The second is that drug use is a crime and should be dealt with through the array of threats and sanctions available to the criminal justice system.

For the past two decades, the latter approach has dominated American law and politics. As a result, the country's jails and prisons now house a half million drug offenders -- a more than tenfold increase since 1980 -- and another half million prisoners convicted of drug-related crimes. California has the largest prison population in the nation and the second-greatest number of drug offenders, after Texas. Prop. 36 represents an attempt to shed this dubious distinction by merging the two opposing approaches: treating addiction as if it were a disease, but within the context of a system that continues to define it as a crime.

Advocates of the measure marketed it as a means to cut costs. The nonpartisan state Legislative Analyst's Office bolstered this argument by estimating that Prop. 36 would save taxpayers $1.5 billion over the first five years: A prison bed in California costs more than $25,000 a year, while treatment averages $4,000.

The strongest opposition to Prop. 36 came not from law-and-order types but from proponents of drug court, a decade-old program that operates in more than 20 states. Like Prop. 36, drug courts -- which handle a much smaller proportion of offenders than does Prop. 36 -- rely on treatment as the preferred response to drug offenses. The primary difference is that drug court judges retain the discretion to impose short jail sentences to "wake up" recalcitrant users and inspire cooperation. Prop. 36 removed that discretion, allowing judges to impose jail time only after a defendant has tested dirty or skipped out of treatment three times and been found "unamenable to treatment."

"Judges like options," says Cunningham. "We don't like to be in a corner where there's nothing we can do but incarcerate. But we also should not be put in an all-or-nothing position of not being able to impose an interim sanction" -- such as jail time.

Others suggest that Prop. 36 may not go far enough. A Prop. 36 conviction, points out Jordan Schreiber, a public defender in Contra Costa, is no free ride. "It's onerous," says Schreiber. "You're going to be offered treatment, but you're also offered all kinds of sanctions. You're on probation for three years with a search clause, so the cops can stop and search you at any time. You have to report to a [probation officer] and to drug treatment. You pay $50 a month for probation fees, a $400 fine to the court, and you're charged for drug treatment on a sliding scale."

A drug conviction also can make an offender ineligible to receive welfare and disqualify him from getting a student loan or public housing.

"If you or I had a drug problem, we wouldn't go and get ourselves arrested in order to get treatment," notes Mark Mauer, assistant director of the Sentencing Project in Washington and the author of "Race to Incarcerate." "Low-income people don't have access to the treatment on demand that middle-class people with insurance do. We haven't tried providing unlimited treatment slots. Would a third, half, 100 percent take advantage of them? We don't know."

Prop. 36 and similar measures, Mauer says, "make sense, given that the criminal justice system has become our model for responding to social problems in poor communities -- but that's a big given. Things are at such an extreme that that doesn't even get questioned in public debates."

In the political context Mauer describes, it is the economic -- rather than the moral -- argument for drug treatment that has gained growing national resonance. Incarcerating drug offenders in state and federal prisons costs taxpayers $5 billion a year. In 2000, corrections overall consumed 7 percent of state budgets.

In the past, prison budgets have held firm even in tough times, but that is beginning to change. As state budget deficits head toward an estimated $85 billion total for 2003, half the states have cut their prison spending, and several have repealed or reformed mandatory sentencing laws that impose long prison terms on drug offenders. Governors in Ohio, Illinois, Michigan and Florida have closed prisons. Newly constructed prisons in Illinois, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin have remained shut because legislatures have not appropriated the funds to open them.

In recent months, as budget deadlines loomed, this trend has accelerated. Lawmakers in one state after another have proposed, approved or implemented a shift away from incarceration toward treatment and community supervision.

A few examples:

Traditionally tough-on-crime Republican governors and legislators -- including, in some cases, the authors of the unforgiving sentencing laws that are now being revised or repealed -- have introduced many of these reforms. Republican politicians have even taken to using a new slogan to describe their approach: "Smart on crime."

The explanation for this conversion may lie in polling numbers as well as red ink. During the '80s and '90s, when harsh drug laws were passed one after another, the conventional wisdom was that once these laws were on the books, they would be untouchable: Being seen as "soft on crime" was electoral poison. Several large, recent public opinion polls have challenged this assumption. A 2002 poll conducted by Peter D. Hart Research Associates for the Open Society Institute found that two out of three Americans perceive drug abuse as a medical problem that should be addressed primarily through treatment. The majority of Republican voters polled agreed with this assertion, as did the majority of fundamentalist Christians. Seventy percent of those polled described the war on drugs as a failure. Seventy-six percent favored mandated treatment -- the foundation of Prop. 36.

Legislators and voters finally seem to be figuring out that the old approach to drug use -- wholesale incarceration -- is literally bankrupt. At the same time, decriminalization is not in the cards. Last year's marijuana legalization initiative in Nevada flopped. The Bush administration, while paying some lip service to the notion of treatment (particularly for close relatives of the president), has displayed a steadfast loyalty to the guiding tenets of the old war on drugs -- raiding the homes of elderly and frail medical marijuana patients; sending John Ashcroft north to try to scare the Canadian prime minister out of legalizing marijuana; and straining to update the drug war's image by tying it to the more popular war on terrorism. Even hardcore reformers have concluded, through focus groups and polling, that Americans still want the police and the courts in charge of drug offenders; they are not interested in setting drug users free entirely, or in handing them over to the health department.

"We don't run initiatives to lose them," says Daniel Abrahamson, director of legal affairs for the Drug Policy Alliance, who drafted Prop. 36. "The public would not have gone at this point for ending prohibition, but treatment vs. incarceration was an easy one for them."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

In a small conference room at the Contra Costa County Department of Probation, Prop. 36 clients struggle to explain themselves to a probation officer, a treatment provider, and two representatives of the Recovery Gateway Unit, the county office that coordinates Prop. 36 care. Prop. 36 clients come before this hybrid tribunal -- a cross between an encounter group and the principal's office -- at the beginning and end of their treatment, and whenever they slip up in between.

Christopher (all participants' names are changed), is the first to appear. He looks like a college kid in jeans and a white T-shirt, his straight brown hair in a shaggy layered cut. His bad teeth are the only visible sign of his long-term addiction to methamphetamine. Users' drugs of choice vary from county to county -- in Contra Costa, 60 percent of clients use meth as their primary drug. Meth is also the most popular drug among Prop. 36 clients statewide, at 44 percent. Cocaine and crack are next at 15 percent, followed by heroin at 14 percent.

"I know I was supposed to set up an appointment" to resume treatment after a lapse, he begins, launching into what will be a familiar refrain, "but I didn't know how to go about getting the phone number." The excuses, while plentiful, are also fairly credible. Each Prop. 36 client is responsible to several authorities -- probation, a treatment provider, the Recovery Gateway Unit, sometimes the child welfare department -- and drug users' lives are often chaotic enough to make fulfilling these simultaneous mandates a genuine challenge.

"We didn't know where you were," says Prop. 36 program manager Lenny Williams, a sunburned man with the ice-blue eyes of a Marlboro cowboy. "You have two treatment failures. I wonder if you are still confused as to what you have to do?"

The proceedings are immensely polite, as ritualized as typical courtroom behavior but several degrees milder, designed to instill trust rather than respect and fear. But if Williams can afford to speak softly, it may be because ultimately, the court still carries a big stick: One more treatment failure and Christopher will find himself behind bars.

"I'm sick of going to jail," Christopher concedes.

"It's really important, Christopher, that this time you follow through," Williams scolds gently.

"I will," promises Christopher, as solemn as a groom. He dutifully recites the date and time of his next appointment, then asks to borrow a phone so he can call his mother for a ride.

For others, the stick is not quite big enough to induce such docility. Lester enters carrying bottled water and a leather-bound planner, a pair of sunglasses hanging from his neck. He had been close to completing an outpatient program when he tested positive for meth. He uses the drug, he informs the group, to manage his depression-- "to get my ass out of bed, take a shower if need be."

In recent weeks, Lester's mother set him up with a chiropractor who specializes in "nervous system things." His doctor has put him on Wellbutrin. That, he implies, ought to be sufficient.

Williams has a different plan for Lester: His probation will be extended and he will be referred back to outpatient.

"Can I ask what you're doing over there for treatment?" Lester asks with exaggerated politeness, directing his question to a representative from the program he previously attended. "Has anything changed over time? Because I don't consider listening to a meditation tape for 45 minutes treatment."

"We don't do that anymore," she says flatly.

Lester's impertinent question ---what exactly qualifies as treatment? -- goes to the heart of the challenge California faces as it scrambles to serve the 36,000 users who have poured into rehab since Prop. 36 went into effect. For the initiative to demonstrate the kind of long-term success that will ensure its survival ---not to mention its replication -- those funding and implementing it will have to ensure that clients get high-quality treatment tailored to their individual needs. That will take not only planning and oversight but also money, a commodity in increasingly short supply.

At the national level, research is showing that even relatively costly, high-end treatment can save money by helping to stop both drug use and its associated crime. A five-year evaluation of Brooklyn's Drug Treatment Alternative-to-Prison program found participants 87 percent less likely to return to prison than those who were simply incarcerated and released. The program provides repeat offenders with as much as two years of residential treatment -- more than six times the national average -- as well as vocational training and social and mental health services. Even this intensive level of service, researchers found, costs about half what it would have to incarcerate the same offenders. (By way of contrast, a study by a consortium of the Claremont colleges found that California's harsh three-strikes law has done absolutely nothing to reduce drug offenses.)

More broadly, a much cited RAND Corp. report concluded that every dollar spent on drug treatment saves more than seven in drug-related costs. There is mounting evidence that drug treatment can have a tremendous impact on the lives of the children of drug users -- and on the costs associated with their care. Researchers at the University of Chicago, for example, recently concluded that child welfare costs added $18.8 million to the $147.5 million spent to lock up women from Cook County alone in 2000.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

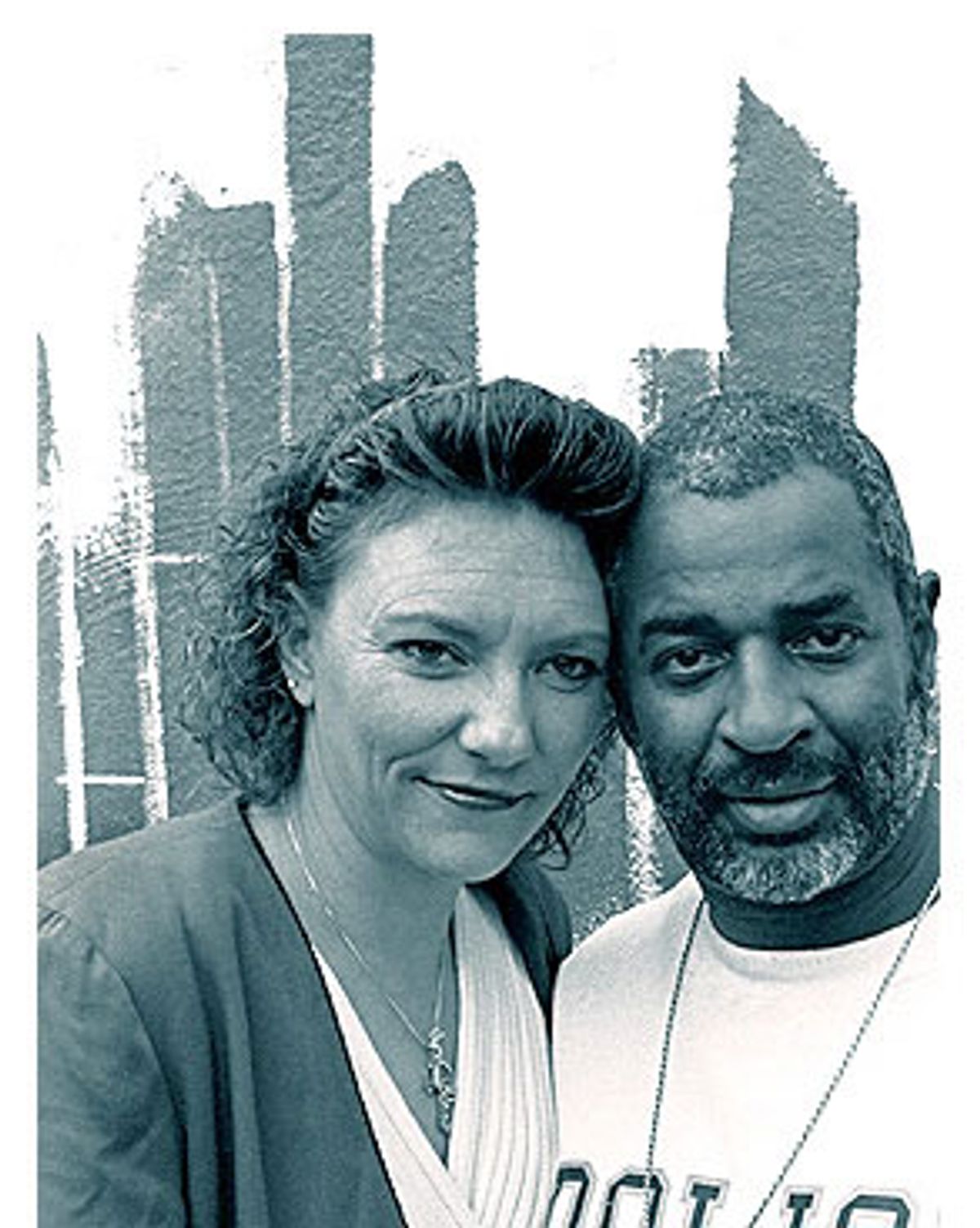

Zina Carse perches on the couch of the Oakland home she shares with her boyfriend CJ and his grandmother while CJ brings her breakfast -- bacon, ham, raisin toast. When Carse was using methamphetamine, she would disappear for days, coming home haggard and skin and bones. CJ, a limousine driver, cared for her in the intervals and tried to "fatten her up." Carse has put on 20 pounds since she got clean, but CJ has yet to break the habit of making sure she eats.

An aqua-eyed 39-year-old with feathered, red-tinted hair, Carse pulls out a photograph of herself taken right before she went into treatment less than six months earlier, when she was arrested with methamphetamine in her purse. She is gaunt, pale, with stringy cropped hair, saucer eyes, drawn mouth. The only thing recognizable is her bright pink lipstick, the same shade she wears today.

Being arrested saved her, Carse believes -- she calls it her "God shot" -- but so did being released. "I don't think staying in jail would ever have gotten me clean," Carse said. "What did it was my program."

"Fake it till you make it" is one of several aphorisms ubiquitous in drug treatment settings. That's what Carse did. She was assigned under Prop. 36 to a weekly Thursday afternoon outpatient meeting. She got high on weekends and then stayed clean for three days so her urinalysis would come out negative. That worked fine until she and CJ got in a fight and she used on a Wednesday to console herself. Knowing she would test dirty, she stopped going to rehab.

At that point, CJ gave her an ultimatum: drugs or me. Her probation officer put out a warrant for her arrest. The combination was enough to bring her back in. This time, she was assigned to the Ozanam Center, a drug treatment program in Contra Costa. Her experience there is a testament to the power of intensive residential care in a well-run facility -- the kind of care only a minority of Prop. 36 clients receive.

At "Oz," Carse was introduced to an iconography of healing -- a collection of stories and symbols that helped her understand what had happened to her and what she had to do next. Her addiction was her "red dog," her recovery her "blue dog" -- it was up to her to choose which one to feed. A paper heart torn to pieces represented what she did to those who loved her every time she used.

Carse saw a therapist who helped her deal with the childhood sexual abuse that Carse believes triggered her initial descent into drugs. She took parenting and anger management classes, a class on codependency and another on relapse prevention. She cooked and cleaned and learned to get along with her housemates. She discovered how to relax without drugs, by meditating or swinging on the swing set in the spacious back yard.

After a few weeks, Carse called CJ and told him, "I cannot think of a single reason why I would want to do any dope right now." She couldn't remember the last time she had felt that way.

Next, Carse reached out to her children, who live with their father. When she completed her time at the Ozanam Center, they came to the awards ceremony. Now Carse sees her kids every weekend, asks them how school is going, checks up on their grades. "They're proud of me," she said. For now, that's enough.

Carse is well aware that many Prop. 36 clients are "perpetrating" -- manipulating a system they perceive as permissive and going back to drugs at the earliest opportunity. They're just not ready yet, she says -- but Prop. 36, unlike the system that preceded it, gives them the time and opportunity to get there.

"Prop. 36 is a big opportunity to save a lot of lives," Carse says, "where jail wouldn't."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

There is no question that the California model is a work in progress. For every Zina Carse, there is another user with a story of bureaucratic chaos, conflicting requirements, unhelpful or even unnecessary treatment. One Prop. 36 client tells of going through treatment in one county only to be required subsequently to serve six months' jail time in another county on a bad-check charge related to her by-then-defunct habit. Another complains that Prop. 36 and the child welfare department couldn't agree on which rehab she should go to; when she followed the orders of one system, she was penalized by the other.

A public defender tells of a client who tried meth once and had the bad luck to be caught; the treatment program to which he was referred was about as useful to him as traffic school. Two teenage girls tell parallel stories: Their addicted mothers were released under Prop. 36 but months passed and they never received the paperwork they needed to begin treatment. One is using heavily again; the other recently received a long prison sentence for a new charge.

Prop. 36, because it requires both addicts and bureaucrats to change long-term habits, faces considerable hurdles. Its impact, and that of the related changes taking place across the nation, is still a drop in the bucket: The nation's prisons remain filled to overflowing with people who are there because they use drugs.

But the hypothesis that Prop. 36 is testing -- drug treatment can save the money, lives and families that incarceration squanders -- is a crucial one. As President Bush's latest round of tax cuts threatens to intensify already dire budget crises across the country, it may finally get the large-scale trial it has long deserved.

If California's Proposition 36 can demonstrate better results than the policy that preceded it, it might do more than save local lives and dollars. It might herald the end of a decades-long drug war -- rife with wastefulness, fiscal as well as human -- that an ailing economy will no longer support.

Shares