Former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean is the only Democratic presidential candidate who has stirred any interest beyond party regulars. He has established himself as the "straight talk" candidate in a field dominated by trimmers and positioners. He has shown Democrats that they can raise money without depending on big donors and soft money from labor unions. Yet if the Democrats nominate him as their presidential candidate, he is almost sure to lose to George W. Bush, and perhaps by a very large margin.

Much of Dean's current support comes because he was the only one of the leading candidates to have forthrightly opposed the war with Iraq. In a Zogby poll taken on April 4, when popular support for the war was at its height, 27 percent of the Democrats "strongly opposed," and 15 percent "somewhat opposed," the war. Many of these antiwar Democrats, whose ranks have swelled since then, look to Dean as their candidate. Dean has also won points from Democrats because he has seemed to be speaking his mind, while John Edwards, Dick Gephardt and John Kerry appeared to be taking a safe political position in favor of the war. Of the leading candidates who favored the war, only Connecticut Sen. Joe Lieberman seemed to be expressing heartfelt convictions.

But Dean's popularity is rooted in more than his opposition to the war in Iraq. While Gephardt or Rep. Dennis Kucinich try desperately to evoke the party's blue-collar past, Dean is the quintessential candidate of the college-educated professionals that began coming into the Democratic Party in the late 1960s and are now one of its key voting blocs. He expresses their political outlook better than any other Democratic presidential candidate.

Professionals are college-educated workers who produce primarily ideas and services. They include engineers, doctors, nurses, teachers, fashion designers, actors, welfare workers, architects and software programmers. They make up about 15 percent of the labor force, and (since they vote in a higher proportion than any other group) about a fifth of the electorate, but they are clustered in large metropolitan areas like the San Francisco Bay Area, Chicago, Boston, New Jersey's Bergen and Mercer counties, and the North Carolina Research Triangle. In the 1950s, they were the most Republican of occupational groups, but over the last 30 years they have swung to the Democrats, and in the last four elections, on average, they backed Democrats over Republicans 54 to 42 percent.

Their political outlook is very different from the blue-collar or minority Democrats who entered the party earlier. They retain the skepticism of "big government" that in the 1950s led them to vote Republican. They worry about budget deficits and government waste and bureaucracy. But as they have become subject to the market priorities of large insurance companies, software conglomerates and foreign-owned publishing houses, they have abandoned their support for a simple model of unfettered capitalism. They don't like big government, but they like the idea of strong public regulations that will protect the environment and consumer safety and prevent corporate abuse. They don't worry about their class interest, but they worry about managers and politicians acting in the public interest.

These college-educated workers are also products of the social and cultural revolution that began in the colleges during the 1960s and has steadily swept through the country. They avidly support women's rights and civil rights and tolerance toward gays. They are fiscally moderate or conservative and socially liberal.

Howard Dean is the product of this social transformation. He graduated from Yale in 1971 and from medical school in 1978. As Vermont's governor, he took pride in balanced budgets and his support for welfare reform. At the same time, he championed environmental protection, guaranteed health insurance for children under 18, and signed the country's first law granting gays the right of civil union. As a presidential candidate, he has continued to blend fiscal conservatism and social liberalism. Asked at an Iowa forum how he would encourage economic growth, he said his first step would be to balance the budget. That's not what a New Deal Democrat like Kucinich or Gephardt would say, but it is entirely consistent with the outlook of the professionals who have entered the Democratic Party.

While some of Dean's critics call him a "populist," he also studiously avoids what he calls "class warfare." He's not against the Bush tax cuts because they favor the rich, but because they squander scarce public resources that could be used to broaden access to healthcare, improve education, and get the economy going again. Like any other Democrat, Dean would like to attract the enthusiastic support of blue-collar ethnics or urban minorities, but they are not part of his base. His support is in places like Austin, the Bay Area and Seattle, and among the people who use and give money on the Internet.

As the proportion of professionals in the workforce grows -- driven by the transition from an industrial to a postindustrial capitalism -- a candidate like Dean may eventually command a majority of the national electorate. Positions that now seem maverick -- like Dean's support for civil unions -- will eventually become mainstream, as women's rights and support for environmental protection have become. If Dean himself can gather a modicum of support from blue-collar and minority Democrats, he might even be able to win the Democratic nomination for president and face George W. Bush in the general election. The Democratic field this year is pretty mediocre. But if that does happen, it could lead to a long and unhappy fall for Democrats. Some of the factors that make Dean attractive to Democrats will not endear him to independent and Republican voters.

Dean's opposition to the war in Iraq may help him in the primary -- and has certainly helped make him a credible candidate -- but it is likely to hurt him against Bush. Even if the United States remains bogged down in Iraq, and even if popular doubts about the invasion and occupation grow, Americans are still likely to credit Bush with trying to wage a vigorous war against terror. And they will consider voting for a Democratic candidate only if they believe he can do likewise. The Republicans will argue that an antiwar candidate like Dean who has no foreign policy experience is ill-equipped to protect the country from attack. And a lot of people will believe those charges. At the least, a candidate like Dean will have to spend a vital part of his campaign defending his credentials on homeland security and the war against terror rather than attacking Bush's economic program. Think of Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis (who, unlike Dean, served in the armed forces) unsuccessfully defending his foreign policy credentials against Bush's father in 1988.

Dean's support of civil unions for gays would hurt his candidacy among culturally conservative voters who might otherwise back a Democrat. Another Democrat might be able to get away with supporting civil unions, but Dean is already closely identified with the issue, as Al Gore was identified with environmentalism in 2000. In general, Dean's antiwar stance and his identification with gay rights would cause him difficulty among white working-class voters in the Midwest and the South. Democrats don't have to win majorities among these voters, but if they can't win at least 40 percent, they won't be able to win traditionally Democratic states like Arkansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Ohio, Tennessee, and West Virginia. Bill Clinton was successful because he could speak to professionals in Silicon Valley and autoworkers in Fenton, Mo. Gore couldn't win those states largely because he was too culturally identified with the Northeast, with college-educated professionals, and with postindustrial social liberalism. Dean suffers from the same political disability.

To put it in regional terms: Dean, a culturally libertarian New Englander who opposed the war, could virtually forget about winning any Southern or border states. Southerners are willing to support a Southern Democrat like Clinton with whom they can identify, but they will not vote for a Dukakis or Dean. Dean would not simply get trounced in the South: His candidacy would allow Bush to take the entire South for granted and move all his resources into states like Michigan and Pennsylvania that the Democrats have to win. In the end, Dean would be lucky to hold on to Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, D.C., Maryland, Illinois, Minnesota, California, Oregon, and Washington.

Wouldn't the other candidates do just as poorly? If Bush's popularity remains high, they might also be trounced. If, however, the economy continues to falter, and if Americans become skeptical about the benefits of the invasion and occupation of Iraq, a Democrat could defeat Bush -- though only if the election pivots on Bush's successes and failures and not on the qualifications of his Democratic opponent. The Democrats would be much better off in that case with a blander, more faceless, less exciting Kerry, Gephardt or even Lieberman (perhaps with Edwards, Florida Sen. Bob Graham, or retired Gen. Wesley Clark as running mate) than they would be with a fiery, controversial Dean.

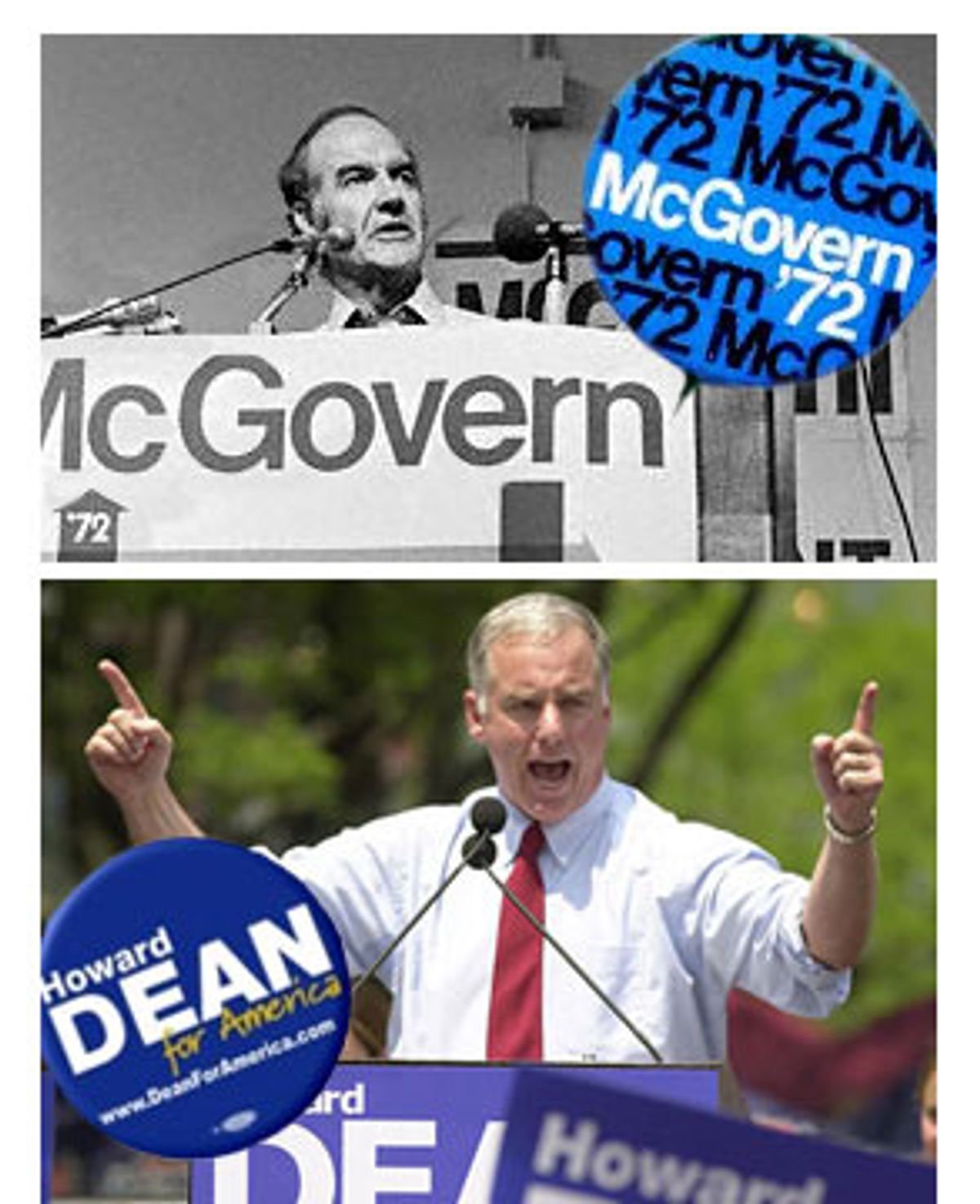

Dean's detractors most often compare him to the 1972 Democratic nominee, George McGovern, who was routed by Richard Nixon in the general election. The comparison is apt in more ways than one. McGovern was the first Democrat to capture the imagination of the students who would become professionals and lead the social and cultural revolution of the past 30 years. He pioneered direct-mail fundraising. And many of the Democrats' most innovative politicians and political consultants, including Gary Hart, Pat Caddell, and Bill and Hillary Clinton, got their start in the McGovern campaign. Dean enjoys this part of McGovern's legacy. But he also, sadly, may suffer from the other side of McGovern's legacy. Just as the country was not ready for McGovern in 1972, so it is probably not ready for Howard Dean in 2004.

Shares