As dusk turns to darkness, a group of women wait in the shadows, eyeing a boldly lit truckers’ bar. Here at the crossroads, road-weary long-haul drivers stop for the night, heading for the bars in search of beer and women. Most nights, Inchope’s female entertainers enter with guitars, tambourines and sexual come-ons. But tonight, they come carrying condoms, and the songs they sing are about preventing the spread of AIDS.

In this beautiful, beleaguered African country of 19 million, nearly 2 million people, or one in eight, are HIV-positive — among the highest rates of infection in the world. Along the Beira Corridor, Mozambique’s main commercial conduit, local infection has risen to catastrophic levels — above 24 percent. In the bars and clubs clustered along the road, the HIV virus is passed from truckers to prostitutes and back to other truckers, and then on to family members.

Having survived brutal colonial rule, floods and famine, and a 16-year civil war, Mozambicans now find themselves ravaged by AIDS. The pandemic has hit sub-Saharan Africa harder than anywhere on the planet, a fact underscored when U.S. President George W. Bush, during his trip to Africa last week, urged South African president Thabo Mbeki to take more aggressive steps to fight the disease. As denial and bureaucratic red tape block aid and action, citizens’ groups like Inchope’s sex workers are playing an increasingly important role in the struggle to prevent the HIV virus from spreading.

The distance from the capital city of Maputo to Beira, Mozambique’s key Indian Ocean port, is perhaps 500 miles. Yet the loose network of roads between them is so pocked and rutted that it can easily take three days to travel by car. Instead, like anyone with hard currency here, I fly north to the sweltering colonial port, the starting point of the Beira Corridor. At the airport I’m met by a friend, Jose, a former fighter with FRELIMO, the resistance movement that battled Mozambique’s Portuguese rulers and ushered in a curious Marxist-Leninist system after the colonialists abruptly departed in 1975. After years of teaching high school science in the San Francisco Bay Area, Jose and his wife, a California nurse, recently returned to Mozambique with the idea of making a contribution to its future. “So finally you get a chance to see our little country,” he says with mock humility as we begin the drive inland.

At the Beira docks, truckers are loading their rigs with merchandise before heading east for the long haul to Zimbabwe, Malawi and the African interior. As we head out of town, Jose grows despondent: Along the waterfront, the once-elegant 1950s hotels, built by the Portuguese and nationalized after independence, are dilapidated and abandoned except for homeless squatters. Their campfires glow inside the walls, giving the hotels the appearance of a warren of caves.

In an outer district, we stop at an orphanage: Scores of toddlers and infants squirm on the polished cement deck, their parents claimed by the floods that ravaged Mozambique in 2000 — or by AIDS, which crept up more silently in the late 1980s and has left nearly half a million orphans. Up and down the coast, meanwhile, wealthy South African entrepreneurs are buying up Mozambique’s white-sand beaches and azure waters, creating $300-a-night resorts.

Entering the Corridor, we’re flanked by slow-rolling panel trucks stuffed with goods and passengers. Fifty-ton big rigs whip past us, eager to cover ground before nightfall. By and by, the verdant coastal land dries out, making way for desolate hill country. At tiny settlements en route, adults and children race toward the road with armloads of dwarf pineapple, green mangoes or charcoal, beseeching the truckers to buy.

Given that the Beira Corridor is the main transportation and commercial artery in and out of central and northern Mozambique, it seems a logical place to funnel state funds. But as the lamentable state of the road attests, the money’s going elsewhere.

In the 1990s, war-ravaged Mozambique switched from FRELIMO’s socialist system to a free-market economy — a structural revamping required by the IMF, the World Bank and international aid agencies. Since then, while infusions of global capital have greatly increased the variety of imported goods, they have also greatly widened the gap between haves and have-nots — and given rise to government corruption on a grand scale. Throughout the country, ordinary Mozambicans curse the now-endemic “corrupcao.” And so here, along the vital Beira Corridor, potholes bounce our jeep skyward; every few miles, there’s a rig with a bent axle or an overturned container alongside the pavement.

In the early afternoon, just as the air gets fresh and we enter the highlands, we come to the Inchope crossroads, at the heart of the Corridor. A riot of stalls, kiosks and bars covers every inch of roadside, all catering to the truck drivers. While life on the road is relentless, and drivers’ earnings a pittance compared to the fleet magnates that hire them, in such dirt-poor zones, they are virtually the only source of regular income for families. To locals, truckers are the high rollers. They come loaded, as one prostitute put it, “with cash and STDs.”

Just before I left for Mozambique, a friend who had lived four years in the Congo gave me some valuable advice. “When you meet people in Mozambique, don’t walk in asking questions about how AIDS has affected them. Start by telling them that there’s a problem here in your own country. That there are many people in the U.S. who’ve died of AIDS, friends whom you’ve known. Only then, they may be willing to talk with you. Africans are sick of having Americans and Europeans acting as if AIDS is an “African problem.”

Now, a week after Jose and I set off from Beira, I find myself unexpectedly back at Inchope — invited by a local women’s group known as OMES, the Organization of Women AIDS Educators. Founded in 1994 by women alarmed by HIV’s ravaging of communities, OMES began to provide counseling, education and treatment services for local prostitutes. Over the past decade, their counseling projects have begun to receive small amounts of funding from British and German NGOs.

On this day I accompany the group’s coordinator, Joana Siahamba, to the Inchope crossroads. There OMES will hold a weeklong workshop, training sex workers to teach their neighbors and customers about AIDS and AIDS prevention.

At dawn, Siahamba comes around in OMES’s ivory-white pickup, then backtracks along the Corridor toward the settlements that ring Inchope to gather up the women who will attend the workshop. Most of the women are single mothers with children. Siahamba knows from experience they are preoccupied with daily survival, and may not show up unless transportation to the site comes right to them.

It is the peanut harvest, and as we drive along the Corridor in the early-morning mist, legions of displaced or destitute farmers, hoes across their shoulders, head out to marginal plots of land, often two or three hours’ walk away. Here, the tiny, tough red peanut is the main protein source for the thousands who lost out when collective farms went private in the early ’90s and loans for subsistence farmers dried up. Like most people in Mozambique, one of the four or five poorest countries in the world, they are just barely hanging on.

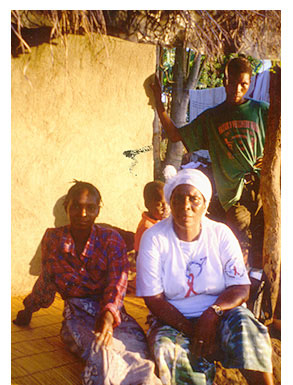

The OMES workshop begins in a large, round gazebo with stucco walls and a cone-shaped, thatched roof — the same place that many of the women work at night. The 18 women gathered are ordinary Mozambicans — carefully groomed, as is the custom in these parts, but casual in T-shirts and bright flip-flops. Like the OMES workers, most range in age from their early 20s to their early 40s. Many seem tired. Some spot familiar faces; others are strangers, and eye each other warily. The gathering of women feels oddly familiar: There are the aloof ones; the social negotiators; the big sisters; the comics; the vivacious; the impenetrable.

To ease the tension, one of the new participants, a sturdy, take-charge woman with turquoise pants and tiny dreadlocks, calls the group into a circle. They begin a slow, synchronized dance and a cappella singing, a customary icebreaker in this region.

Glancing down the row of chairs where the women are settled in, I encounter a gaze that cuts like a laser. On a continent where all eyes are a deep, loamy brown, the eyes looking back at me are strange and startling — flat, jade green like glass, like the Indian Ocean where it nears the shore at Beira. Here, eyes like these are said to be the legacy of seafaring Arab traders who, beginning in the 10th century, plied Mozambique’s 1,500-mile shoreline. Or perhaps they are the mark left by some white Rhodesian farmer like those who today are streaming across the nearby border after the recent land confiscations in Zimbabwe.

The eyes belong to a young woman named Eileen. At the break, she asks me if I’ll be heading to Harare, in her native Zimbabwe, and if I can possibly deliver money to her mother there. She and her husband, who brought her here to work, would like to return home as soon as they earn enough rand to do so. When I ask when that might be, Eileen tilts her head and says nothing; her jade eyes look away.

In upcoming days, seated before a blackboard drawing of the male and female reproductive organs, the women will cover basic anatomy and physiology, how the HIV virus is spread, and how condoms can act as a barrier. But OMES’s leaders reserve the first day for a discussion of the participants’ daily life and work. “Why do women sell sex for money?” Siahamba asks. “Who has an opinion? Who goes into sex work and why?”

Anyone expecting an idyllic consciousness-raising session would find their hopes dashed. “Women sell themselves because they are bad,” says Nelda, a slim woman in a floral skirt at the back of the gazebo. “Because they have no moral character.”

“They are lazy! They don’t want to work,” volunteers another.

“They want to steal other women’s husbands. Eh! They do!” adds a lively pair standing near the doorway. The young women alternate between Portuguese — Mozambique’s colonial tongue and its national language — and Shona, the lingua franca of the region. Listening to them talk disparagingly about sex workers — as if speaking about someone other than themselves — I wonder if they have absorbed society’s contempt for prostitution, or if they are merely saying what they think people expect them to say in public.

Siahamba’s face registers a weary patience. She prompts the class to break up into smaller sessions to discuss the same subjects in a more private, fresh-air setting, where greater candor and reflection can occur.

Outside, Manica’s sugarloaf mountains loom above the bare ground of Inchope, and the women gather there in groups of four below the acacias. The OMES team hands out new paper pads and pens — items put straight to use during the breakout discussions, and rare enough that the trainees pose with writing instruments in hand, as if poised to take notes, for a group photo portrait.

In the course of the group discussions, a small girl with a halo of curls catches my attention. Gangly and giggling, she tries to goad older girls into a game of tag. I ask a couple of women who have been welcoming to me about her age. Isn’t she young? She’s 15, they answer. But from the girl’s lack of grown-up poise and barely budding breasts, I’m not convinced. Her family sent her here to work, the two add, as if to make it more acceptable. The effect for me is the opposite, and while I make no overt comment, I unintentionally grimace for a moment — a message as unmistakable as if I’ve said aloud: “Surely her family must be able to find another solution?”

Just then, I glance up, feeling Joana Siahamba’s hard stare. In earlier talks at the OMES office, Siamhamba has been personable and engaging. Now her eyes flicker with a hint of ire, like a protective mother determined to shield her children from imminent harm.

I decide to drop it, to look around and learn what I can. In the evening, we backtrack along the Corridor in the OMES truck. We’re headed for Chimoio, capital of Manica province, and the largest city in the Mozambican interior.

To an American, Chimoio most resembles some broken-down Oklahoma town after Wal-mart has packed up and left. Among Mozambicans, Manica is known as a rich province and Chimoio a place that has everything, where a hardworking man or woman can surely find a job.

The reality is different. On the outskirts of Chimoio, the sprawling, ghostly TechnicaMoz complex lies abandoned. Once among the most important textile mills in the country, TechnicaMoz produced reams of capulanas — the brilliantly printed cotton wraps Mozambican women fashion into skirts, headwear and baby carriers. A decade ago, due to mismanagement and lack of capital, the factory closed its doors. When it did, hundreds of local families lost their source of livelihood.

As throughout East Africa, Chimoio’s handful of storefront shops are owned by Asians — Indian or Pakistani immigrant merchants — and staffed almost exclusively by their families. Here, one can find specialty items such as a drafting tablet or Pond’s facial cream. But the dog-eared pad will be 5 years old, and the moisturizer costs the equivalent of a week’s food. Instead, the average Manican buys manufactured goods — enameled tin plates, tools, second-hand clothing — at the local open-air market.

Here in Chimoio, the First World’s safety net of menial, low-wage jobs simply does not exist. While an uncle or a second cousin may secure work as a security guard or servant for international aid offices, for the great majority, there is no work at all: no McDonald’s, no lawns to mow, no streets to sweep, not even toilets to clean. For families in the region, the passing truckers’ money is the surest guarantee of survival, and the commodity the drivers wish to purchase is sex.

Back at the OMES workshop, participants gather again to analyze the work they do. In the small breakout groups, the women have spoken more freely. Indeed, by day’s end, the few sex workers still toeing a self-deprecating line are shouted down by others incensed about the stingy, precarious economy, the corruption and the virtual disappearance of the clinics and basic education that existed under FRELIMO’s 1980s socialist regime — a regime that, while too dogmatic and unskilled to achieve its grand ambitions, at least provided basic education and health services, for the first time, to most Mozambicans.

Riled up or lost in thought, OMES’s trainees filter out of the compound just before sundown. Nascent pride and anger will spur a number of these women to become vocal AIDS educators in their communities. It’s a decision they don’t make lightly. Although OMES’s undeniably effective work today elicits a certain degree of admiration in and around Chimoio, the original activists and counselors were ostracized for admitting what they did to make a living. Even today, while women who support families as sex workers are expected to send money home, they are not welcome to return there.

Standing at the Crossroads and looking eastward toward the mountains, my thoughts wander back to the events of the 1970s and ’80s, when thousands of young Mozambican men were forced to put their bodies on the line — first, fighting against the brutal rule of the Portuguese; later, defending the country from vicious attacks by the white-supremacist regimes of South Africa and Rhodesia and finally from RENAMO mercenaries who massacred whole villages, routinely leaving alive a pair of terrorized witnesses to recount the details. These sons had little hope of surviving the war or taking part in the new society they hoped to build. But they did what they had to, for their communities and their families. They are justly regarded as heroes.

Here, in the dusty fields of Inchope, I see a situation that is in many ways parallel. But this time, it is Mozambique’s daughters who have placed their bodies on the line, defending their families from a massacre of a different kind — slow starvation. Instead of bullets, they face a lethal virus. And yet the reward for their sacrifice is not veneration, but exile and ostracism. And their chances of survival are even slimmer than that of the boys who went to war.

A month later, in Maputo, I ask a public health nurse how many of the sex workers I met in Inchope are likely to contract the virus? Her answer: Close to 100 percent.

At noon, the workshop breaks for lunch, and the trainees head for the doorless entrance of a nearby building — a low-ceilinged club where many of the women entertain truckers by night. Inside, the bar owner comes round with a platter holding fried egg sandwiches and a soda for each trainee; both count as a considerable luxury.

Jumbo hand-painted posters of Michael Jackson, Bob Marley and South African reggae star Lucky Dube lend the nightspot a good-time air. Still, Manica’s weighty history is never far away: Wrapping round the dance floor are folk murals of Ian Smith’s Rhodesian air force bombing local villages to smithereens, and — painted in touchingly gentle strokes — Rhodesian prisoner-of-war camps with guards feeding poison to Mozambican refugees. (Local doctors and nurses confirm that this actually happened.)

Back at the table, the club’s manager, a plump-faced woman with a brash manner, presides over the luncheon. After methodically pocketing payment for the food, she sits down and listens in, fingering the heap of free condoms Joanna Siahamba has deposited on the tabletop. Intrigued by the lively discussion of condoms and STDs, she inches closer. “You know,” she says, inserting herself in the conversation, “I’m going to put a packet of these damn things in every room,” gesturing toward the cement huts outside where women service the truckers. “In all the years I’ve spent running this place, I don’t think I’ve ever seen one of those guys put on an overcoat.”

OMES activists and counselors devote 20 hours a week to community HIV education, including condom distribution and street theater, in bars, marketplaces and communities. For this, they earn between $12 and $19 a month — a significant subsidy in a country whose average monthly income is estimated at between $85 and $214. Their efforts have apparently born fruit: A local Chimoio health group known as Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices, or KAP, reported that 97 percent of all local sex workers the group surveyed had been given classes, counseling or condoms by OMES. Still, the crucial question — the number of men who have actually opted to change their behavior and use condoms — is extremely difficult to answer.

Sex workers’ wellness has rarely been the first item on the agenda for health ministries in southern Africa — or anywhere else, for that matter. In the early 1990s, Kenyan doctors identified truckers as major HIV “vectors” (epidemiology-speak for insects or organisms that transmit pathogens) in sub-Saharan Africa, and a number of studies since have tracked drivers’ activities and their health. The same cannot be said about prostitutes and their health.

In Mozambique, as in many poor countries, no nationwide government studies have been done on sex workers. In most cases, public health workers must glean epidemiological data from nearby regions. In one such study, a 2002 survey carried out at a truck stop in Messina, South Africa (a crossroads much like Inchope), 60 percent of the truckers, many of whom also pass through Mozambique, reported having had STD-type penile ulcers and discharge in the previous six months. Of those men, one in five went without treatment.

In that same South African Medical Research Council report, fewer than half the 320 drivers surveyed claimed they consistently used condoms with prostitutes; 30 percent said they never did. One in three told researchers they always stopped for sex at truck stops. Seventy-five percent had wives or girlfriends, with whom they said condom use fluctuated. And 56 percent of the truckers tested HIV positive. Yet why the truckers risk unsafe sexual activity and block out the danger to their families is perhaps not such a mystery: Life on the road is wrenchingly hard; the HIV virus is invisible and the rumors about its origin myriad.

Given that sex workers desperate to earn money haven’t the clout to insist on condom use, I was curious about what other options they had to protect themselves. Alternatives to the male condom are hard to find. Asking around at possible outlets for female condoms — latex sacs that can be inserted into the vagina to line and protect it — the only sample I came across was in a pharmacy in a posh quarter of Maputo. At about $1 apiece, these devices are far beyond the reach of the average sex workers. AIDS health monitors in neighboring Zimbabwe recently reported that prostitutes who manage to find female condoms use them repeatedly with successive customers because they are so expensive. The effect: While the hired sex worker is fairly well protected, STDs can potentially be passed from one trucker to another via contact with leftover infected semen.

As throughout much of the Third World, the HIV epidemic is threatening to destroy Mozambique’s already barely functioning economy. In the beginning, the virus was disproportionately contracted by the affluent and educated professional class — people who had the ability to travel and have more sexual partners than the poor. But in the past decade, the infection has taken off in poor communities as well, where notions that AIDS is carried by mosquitoes, or that an HIV-positive person can contaminate well water (an essential village resource) has led to their expulsion. Widespread, also, is the belief that condoms bring HIV (since both the disease and the prevention device showed up in many rural areas at around the same time) and that, since prostitutes are thought to spread AIDS, sexual relations with a virgin will cure it.

Poverty facilitates the spread of AIDS. Though lethal, HIV is actually less transmissible than many viruses: In strong and healthy people, infection results in only 1 percent of exposures. But malnutrition, malaria and cholera, all common here, weaken the immune system and lower a body’s resistance to HIV. Other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as gonorrhea, chlamydia and syphilis commonly plague both truckers and sex workers and further help the spread of AIDS. In wealthier countries such bacterial STIs are generally discovered and cured early on. Not so in countries like Mozambique, where few have access to adequate healthcare. If untreated, such bacterial STIs cause breaks in the genitals’ soft epithelial tissue, paving the way for the much tinier HIV virus to enter the bloodstream.

Experts say that the STI-HIV link is what accounts for heterosexual HIV infection rates in Africa being much higher than in the U.S. — a difference often cited in the press without scientific explanation. “Such omissions implicate sexuality rather than microorganisms,” a local nurse practitioner points out, “and play into the image of Africa as a place of wild, fantastic diseases with no relation to those people face in the rest of the world.”

In my first week in Mozambique, a popular fifth-year medical student at the national university in Maputo fell to his death after his apartment building’s decrepit elevator gave way. The young man had been greatly loved by his classmates, but his death was doubly tragic in a country that is, for historical reasons, acutely in need of doctors.

Throughout their 400-year colonial reign, the Portuguese barred Africans from higher education. Upon independence, the Portuguese fled Mozambique en masse, taking with them nearly every trained professional in the former colony. As a result, on Independence Day in 1975, only eight doctors remained in the entire country. New M.D.s have been trained since, but there are still 30,000 citizens to every doctor. Nurses and lay health workers have carried much of the load, especially in strapped rural areas.

While no comprehensive data exists for Mozambique, in neighboring South Africa, one out of five health workers is now HIV positive. The Mozambican health ministry has estimated that, soon, AIDS patients will occupy 20 percent of all rural hospital beds. Caring for them will strain to the breaking point the already grossly overburdened healthcare system.

The epidemic has struck hard and fast here. During the late 1970s and 1980s, under siege from the white supremacist regimes next door in South Africa and Rhodesia, Mozambique was closed off — and so was hit with AIDS much later than the surrounding states. In 1992, after the war ended, soldiers and refugees returned and Mozambique reopened its borders with adjacent countries — all of which had higher rates of HIV. HIV transmission skyrocketed. According to the Centers for Disease Control, in that decade, AIDS cut life expectancy in Mozambique by 27 years — or, as one policy analyst put it, “back to what it was in the 1900s.” Each day here, some 600 Mozambicans are newly infected, nearly half under the age of 24.

If efforts to prevent the spread of AIDS face daunting obstacles, attempts at diagnosis and treatment are virtually futile. As in developing countries worldwide, the great majority of Mozambicans do not know their HIV status. The exorbitant price of diagnostic equipment means that there are only three clinics in the entire country where a person can be tested for HIV. Costly antiretroviral drugs, $350 a year at their subsidized lowest price, lie far beyond the range of the vast majority of the infected. Says one Maputo nurse: “The health establishment is split on the question of how to combat AIDS here. There are those pushing for international aid for antiretrovirals. Others believe the country will never be able to afford them, and that Mozambique must concentrate on home-based care and prevention that will improve a patient’s quality of life.”

In stark contrast to the response to his Middle-East war-making, President Bush’s surprise January announcement that the U.S. would commit $15 billion to fight AIDS in Africa has been received without cynicism. “Most people here are nothing but grateful,” says an American AIDS worker in the capital. “But the question is, as always, if and when that money will filter down.”

At the 2002 International Conference on AIDS in Barcelona, Spain, researchers warned that of the 45 million people worldwide with HIV/AIDS, 28 million are in sub-Saharan Africa.

Indeed, international aid, which today makes up an astounding 60 percent of Mozambique’s earnings of $3.9 billion, ought to have a hefty impact. But too often, restrictions set by international banks blunt its effectiveness. So do red tape and graft, as well as the slating of funds for culturally inappropriate projects that are dreamed up in foreign offices and offer little real help to Mozambicans.

The country’s overwhelming AIDS catastrophe is compounded by eerie silence. Though funeral processions take place every day in cities throughout Mozambique, few people are willing to admit they are HIV positive. Even the newspaper obituary columns in cosmopolitan Maputo resort to euphemisms, every month listing scores of young Mozambicans who have died of “a prolonged illness.” Relatives of the dead generally explain that their loved ones — up to and including government ministers — have died of tuberculosis, malaria, cancer or some rather more acceptable malady. In a culture where death has traditionally been an extremely private matter, social stigma against AIDS and its victims is intense.

As I bristle at the apparent cowardice and hypocrisy, I am forced to recall the sentiment surrounding AIDS not much more than a decade ago in the United States. While the gay community had no option but to face the epidemic, for the general public, the tide of superstition and fear of those with HIV began to turn only in 1991, when basketball superstar Magic Johnson announced to a stunned nation that he had contracted the virus. It took years of example-setting by societal icons — Magic, or Princess Diana visiting AIDS hospices with toddlers Harry and Wills — before Americans began to keep their own dying sons company.

There are psychological explanations for the denial as well: In combat zones, people frequently talk about subjects other than war to keep from going mad. Given the holocaust Mozambicans are facing — and with no cure in sight — how else shall people here continue to function, to survive psychically? There is only so much the human mind can take.

And the silence contains something else: fortitude. Despite AIDS’ bleak reign here, I have not heard a single Mozambican complain of his or her personal misfortune. Having flown in from a country where one is encouraged to divulge every intense feeling publicly, where the most intimate matters are exposed and made thoroughly banal, the grace and quiet depth of emotion here takes one’s breath away, as does the gentleness in everyday interactions among strangers. Mozambicans’ pride is profound but not for public show. Even in the capital, where the newly disenfranchised rob the villas of the nouveau riche, thieves often come to ransack unarmed. And after weeks in Maputo, I did not hear a single gunshot, not even a raised voice.

How the AIDS epidemic spread among human populations is now fairly well documented: unprecedented travel between countries, mass migration from rural areas to urban centers, and income disparities between rich and poor that foster commercial sex, including what social scientists refer to as “transactional sex” — sex bartered for, say, transportation, a chance at employment, or for contraband humanitarian-aid distributions. (While hardly surprising given the level of poverty, instances of the latter were recently reported along the railways in northern Mozambique, to great international disappointment and scandal.)

Whatever the causes, Mozambican AIDS workers say that mass public HIV education is the only effective way to curb the epidemic’s tide.

In Uganda, to the north, an intensive HIV and safe-sex media campaign featuring pop singers, musicians and sports stars is credited with successfully lowering HIV infection rates among the country’s youth.

Health organizations in Mozambique today are slowly following suit. Along the capital’s boulevards and highways like the Beira Corridor, a nationwide pro-condom billboard campaign, aimed at a younger generation of Mozambicans less attuned to indigenous tradition than to MTV, is going head-to-head against the taboo on discussing AIDS.

“Live Positively!” has become the slogan promoted by AIDS public health workers wrestling day and night to improve quality of life for the nearly 2 million Mozambicans already infected with HIV. Fledgling community-based care for AIDS patients may help break the silence now enveloping the disease, as home-care booklets for families become more commonplace, and nurses and medics nationwide advocate for the HIV-infected patients in their towns and villages.

Meanwhile, Africa’s ruling officials are gradually tapping sex workers’ help in the battle against the epidemic, with Uganda again taking a courageous — if slightly jarring — lead: At a recent International Congress on Occupational Health Hazards in Uganda’s capital city of Kampala, health minister Mike Mikula told an auditorium of cheering nurses: “As we continue the struggle against HIV and AIDS, I wish to thank our sisters on the streets for their serious use of condoms. Though the act of streetwalking is not good, these ladies are ensuring the survival of both themselves and their customers in the process of giving them fun.”

In 1999, Mozambican officials under current president Joaquim Chissano also relented, concluding that “prostitution cannot be stopped” and announcing that sex workers’ cooperation must be tapped to help stop the rise of AIDS. In 2001, officials began to advocate education and counseling services similar to those OMES provides to Manica sex workers: Today, under the highway offramp where big rigs rumble into Maputo, and in rural truckstops including those in Inchope, Mozambican doctors such as Ricardo Barrera have set up STI treatment clinics for truck drivers and local women.

Barrera says aggressive STI treatment for truckers makes sense: Men infected with bacterial STIs like gonorrhea and chlamydia often notice discharge and pain on urination. But women who contract these diseases usually experience no symptoms — and so may never know they are infected.

Multiple exposures further raise the risk of contracting any STI — whether bacterial, like gonorrhea, or viral, like HIV. In a 2002 survey undertaken by the Chimoio-based KAP, clients of local sex workers (mainly truckers) reported they had an average of six different partners monthly. The men’s notions about transmission — essential to prevention — were also notable: while 14 per cent believed that HIV could be contracted though a handshake, and 40 percent by kissing — entirely safe activities — a full 97 percent said that oral sex presented no risk at all.

For now, the social stigma against sex workers — and the disease most of them will probably contract — is overwhelming. I think back to Inchope — to Eileen, Nelda, the women arguing, the young girl I inquired about there — and wonder what will become of them, once they begin to show symptoms of AIDS.

Down the road a few days later, I stop by the shantytown of reeds and mud on the outskirts of Chimoio. Clashing with grinding poverty were the jewel-like colors of the late afternoon: the purple and red earth, the ochre glow of adobe huts, the indescribable beauty of Africa.

Alongside a rutted lane, I reach a home run by a group of abandonados — people with AIDS thrown out by their relatives, an increasingly common phenomenon in this region. The group lives together for daily survival, supported by a local church NGO, Kubatsirana. Surrounded by mango trees, the household includes several adults as well as shy boys and girls who rise, according to the gracious manners with which they were raised, to shake my hand before settling in on the mud porch or a tree swing hanging from the mango branches.

These housemates have been cast out of their homes on several accounts: fear that whoever cursed them with the illness will condemn the rest of the family, but also because their families haven’t enough to feed even healthy members. Again, I’m stunned at first by the apparent evidence of cruelty, but then am reminded how common this solution is among human beings during remorseless catastrophe. I think of Ireland, China, the Balkans, the rural United States, in times of famine or drought. It is the weak — usually babies and old people — who are left to die.

They are depressed, the grown-ups tell me. And much of our conversation revolves around how much flesh remains on their bodies. “You see?” says a middle-aged women, patting her thin buttock, “I have nothing, nothing.”

There aren’t many places to sit, and we’re sharing a sawed-off tree stump. Our backs rub against each other so that her frail vertebral column presses into my side.

At a complete loss for words, I finally blurt out: “Here, you can have some of mine” — grabbing a fistful of my own. It is an impulsive joke of the dark, mocking variety that I learned from dying friends in San Francisco.

The air goes silent. The abandonados, startled, are trying to assimilate what they have heard. I am a stranger, a foreigner, unknown. Agitated, they search my expression to make sure they’ve heard correctly, double-checking amongst themselves in whispers, then burst out in laughter. Some, in tears.

“Eh, senhora!” sighs a sinewy old man, smiling and wiping his tears. “E a primeira tarde em que sentimos alegria.” This is the first joyful afternoon we’ve had in a long time.

I would say: It doesn’t take a lot. Once flesh has dissolved, and truly nothing remains except the relationship between one human being and another, joy can be a fairly simple thing.