Sofia Coppola's magnificent and delicate "Lost in Translation" is a love story but not a romance, a picture that fits into no identifiable genre because there's no category fluid enough to properly cradle it. Bill Murray plays Bob Harris, a Hollywood action-movie star who's been flown to Tokyo to make a whiskey commercial, giving him a respite from his kid and his wife of 25 years, with whom he's settled into either a wobbly holding pattern or a businesslike truce that prevents them from killing each other -- it's hard to say which. Scarlett Johansson is a quiet, bookish young woman named Charlotte, who has come to the same city with her hotshot photographer husband (played by Giovanni Ribisi). She clearly cares for him, and yet the two float in parallel spaces that never intersect. They're like strangers who wake up in a rumpled bed together only to realize they've been married for two years.

Charlotte and Bob meet in the bar of the Tokyo Park Hyatt. The two of them have drifted there after spending sleepless hours' worth of channel clicking in their respective rooms, like zombies who can no longer bear the boredom of being undead and need to at least go through the motions of feeling alive.

And after that meeting, everything and nothing happens in "Lost in Translation": The picture's muted intensity isn't just a vague mood -- it's a subtle but very specific type of narrative drive. Coppola (who also wrote the screenplay) is a stealth dramatist: Instead of unfolding in precise pleats, her movies unfurl like bolts of silk. There are no handy place markers between scenes to help us tick off how many minutes are likely to pass between this or that point of conflict and the denouement. Revelations don't click into position; they swoop down, seemingly from nowhere, and settle in quietly, like a bird coming to roost.

To some people, this is a maddeningly diffuse type of filmmaking, but I'd argue that Coppola's precision is simply the sort that's measured in sine waves, not milliseconds. "Lost in Translation" is Coppola's second movie, and it marks her as one of our most gifted filmmakers (of either gender). Her first picture, the elegiac and gorgeously made "The Virgin Suicides," was cautiously praised by some critics, but I remember encountering, in conversation at least, plenty of people who took glee in cutting it down, basing their arguments not on the specifics of the movie itself but on their convenient perception that Coppola was able to make movies only because she has a famous dad, Francis Ford Coppola. Or, more preposterous yet, many refused to acknowledge that she could be a good filmmaker since she had given such a bad performance in "Godfather III."

Strangely enough, or perhaps not so, no one has accused Sofia's husband, Spike Jonze (the director of "Being John Malkovich" and "Adaptation"), of riding on the Coppola coattails, even though, as Lynn Hirschberg pointed out in a recent New York Times Magazine profile of Sofia, Jonze's movies have also benefited from the Coppola family support network. Jonze is not without talent: He's an occasionally entertaining filmmaker. But it's frustrating that he's received so many more accolades than his wife, who is well on her way to becoming a great one.

"Lost in Translation" is a movie about dislocation and the blessed salve of connection. Both Bob and Charlotte are strangers in a strange land, the strange land not being Japan, but their own skins. The very surface of "Lost in Translation" -- it was shot, beautifully, by relative newcomer Lance Acord -- seems alive with nerve endings, from the lonely waltzing molecules of the hotel bar to Tokyo's blaze of blinking neon, which seems both welcoming and reserved. (New Yorkers will probably be struck by how much parts of Tokyo resemble Times Square; it's as if New York has a mirror complement on the other side of the world.) A strong sense of place is a necessity in a movie about dislocation: The city knows for sure who it is; it's the people moving through it who are riddled with doubt and uncertainty.

Bob is undergoing something of a midlife crisis, but it's not the usual kind, perhaps because in Coppola's view, there's no usual anything when it comes to human emotion. He's obviously frustrated with his marriage, but you get the sense he's bound to his wife by some sort of dutiful calcification, if not love. (She never appears; she's merely a surly, disembodied voice on the phone, ringing Bob at all hours to demand a decision on what type of carpet he'd like for his study at home.) Charlotte, who is in her early 20s and who has been married only two years, is far too young to have a midlife crisis. She's youthful and radiant and possessed of a very fine-grained intelligence that announces itself in whispers. But it's as if her heart has aged too fast inside her. Bob first spots her in an elevator, nodding a courteous but bland "hello" to the only other American in that tiny space. Later, they recollect that first encounter. "Did I scowl at you?" Charlotte asks, as if she believes the aura of her inexplicable unhappiness is the first thing anyone would notice about her.

The closest I can come to dissecting the mechanics of Coppola's talent (since you can't dissect alchemy anyway) is this: She frames a movie around her actors instead of around her own vision. Coppola has said that she wouldn't have made the movie if she hadn't been able to get Murray, for whom she wrote the role. He was reportedly reluctant to take it at first, but, thankfully, he did.

Murray has always been an actor of almost subterranean sensitivity (in pictures like "Scrooged," Michael Almereyda's "Hamlet" and "Rushmore"). But this is his finest performance. Murray is often funny here -- his lines loop around us, their unwitting victims, like licorice whips. But he also shows us a range of feelings that we immediately recognize, among them lovesickness, bewilderment, self-deprecating resignation -- such feelings are, after all, universal. But Murray makes them feel new and raw, as if he has locked onto the most universal and most painful truth of all: that even as our bodies age, we're all teenagers inside, susceptible to intensity of emotion and heartbreak that we all think we left behind long ago.

Murray's Bob Harris is a huge star, and the Japanese in particular adore him, relishing even his deadpan surliness. The photographer who's shooting the whiskey ad instructs him, in clear but impressionistic English, that he's looking for sort of a "Rat Pack" mood, only of course (since Coppola delights in all cultural differences, not just those readily deemed politically correct) it comes out "Lat Pack." Bob, bemused, adjusts himself in his chair accordingly: "Joey Bishop, would you like?" he asks, knowing that the joke will sail over the photographer's head, but unable to resist making it anyway.

Early on, he threatens to explode the picture, and I'm talking physically: Coppola and Acord move the camera in so close to Murray that he almost bursts out of the frame, an ungainly Godzilla plopped down in the middle of a petite, orderly country. Then Coppola shows him in an elevator, a very tall man towering above the bobbing heads of a mini-sea of Asians. It's a stunning visual joke: Both literally and figuratively, Bob Harris is big in Japan.

Charlotte is sized much more to scale. When she sets out from the hotel in her boyish, preppy, no-nonsense clothes, she's like a schoolgirl on holiday; even with her resolutely American features, she hardly looks out of place. And yet Johansson shows us the nameless discontent that's like a rumble of thunder inside Charlotte. Despite the difference in their ages, their circumstances, their everything, Charlotte and Bob connect instantly -- it's as if something deep inside each of them is reaching out, with instinctive recognition and relief, for its counterpart in the other.

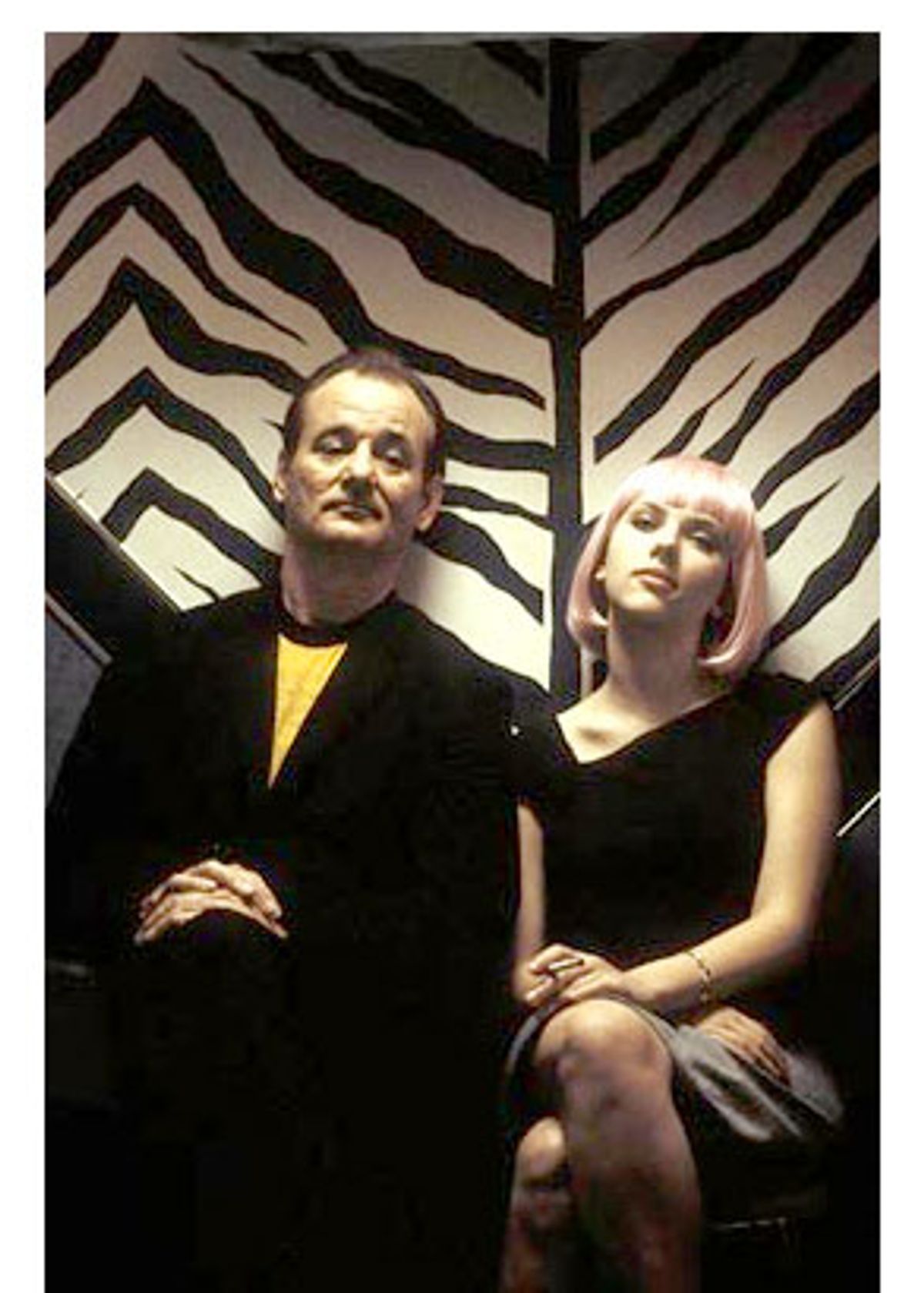

They spar and flirt with each other: Charlotte has some friends who live in the city, and she invites Bob to tag along on an outing. They end up, drunk and boisterous, taking turns at karaoke. Charlotte, having donned a pink Louise Brooks wig, chooses the Pretenders' "Brass in Pocket," and mimes it, purely for Bob's benefit, and with mock seductiveness that's a transparent mask for the real thing. Bob responds with Roxy Music's "More Than This," a song of Byronically lush romanticism. Murray, as we all know, can't sing -- the song comes out in a cracked warble. But he pulls it from somewhere deep inside him, a place where every note is steady and true and right on the money.

Charlotte and Bob fall together and pull away; their tentative movements connect smoothly to form the rhythm of the movie, and it's like the rocking of waves. One sleepless night, they lie awake on the same bed, chastely, fully clothed, talking. Charlotte's husband has gone off for a few days to shoot a rock band in a nearby city. They talk of things that are simultaneously ordinary and gargantuan: Marriage, children, making a living. Bob lies on his back, his body a straight line; Charlotte lies alongside, curled up and facing him, her toes just touching his leg, as if that one small connection point meant everything.

It's a visual hint of the picture's quiet but devastating conclusion -- a moment between characters that's so private, we're not even allowed inside it. But we can see their faces, which tell us all we need to know. In that instant, Coppola and her actors redefine the meaning of the word "lover" -- a lover, we realize, is anyone who loves. The connection between Bob and Charlotte, as Coppola shows it to us at the end of "Lost in Translation," is a moment of intimate magnificence. I have never seen anything quite like it, in any movie.

Many critics and faithful filmgoers often mourn that now long-lost golden age of moviemaking, the '70s, when young directors like Robert Altman, Brian De Palma, Hal Ashby and, of course, Francis Ford Coppola, were stretching the boundaries of what mainstream movies could be. Those days are over. It's not that terrific movies aren't still being made; it's simply that it takes more digging to find them, and no corner can ever be overlooked. Good movies are scattered here and there. There's no wave of bright young filmmakers, working independently and yet unwittingly in tandem, to forge a body of astonishing pictures that will go down in history.

But there's hope in Sofia Coppola. Her movies may not be exactly mainstream (at least not in today's terms), but they're certainly accessible -- there's art to them, but no artiness. And, even more important, no artifice.

If there were more young filmmakers like Coppola, we'd have a movement. As it is, though, we just have a director whose career will be a thrill and a pleasure to watch, and that in itself is no small thing. "Lost in Translation" is such an intimate movie that it feels strange to call it great; physically speaking, its scale is as epic as the human heart is small.

But then, what is an epic but a map of the unmappable? Sofia Coppola works on a seemingly small surface, and yet the emotional landscapes she surveys are as expansive as the ocean. She's not just the progeny of a great filmmaker, but the heir to a tradition. She's our own mini '70s revolution.

Shares