1969 had it all. From Woodstock and Nixon's inauguration to the Manson murders, the Miracle Mets, Chappaquiddick, the man on the moon, Butch and Sundance, the Chicago Eight conspiracy trial, the Beatles' farewell performance, and "Vietnamization," the year was drenched in milestones:

And in late December, 1969 also boasted the greatest week in rock history -- seven days when revolutionary rock 'n' roll, powerhouse R&B, and shimmering pop creations all shared top billing as they never have before or since.

Singling out one week in rock history might seem absurd. Rock's about to turn 50 years old (whether you date its birth on July 9, 1955, the day Bill Haley & His Comets' "Rock Around the Clock" hit No. 1, or on July 5th, 1954, the day Elvis Presley recorded the legendary Sun Sessions) and more than 2,500 weeks have passed since. But there's a unique way to systematically rate rock's past and try to uncover the best single week: simply chose the one that had, album-for-album, the 10 best entries atop the Billboard 200 album chart. A week when the top 10 had no fluff filler, no disposable pop creations, and no dreadful trend imitators. A week that boasted the best collection ever assembled at the pinnacle of the charts at any given moment. Not the 10 best albums of all time, necessarily: that would be too much to hope for. But the week when record buyers produced a lineup of albums unmatched, taken as a whole, for quality, originality and longevity.

The method is subjective, of course, because sales charts aren't perfect barometers of quality. For instance, Bob Marley and the Wailers' reggae landmark, "Catch a Fire," only climbed to No. 171, while the Replacements' post-punk classic, "Let it Be," never charted at all, like hundreds of other worthy titles. And, of course, the charts are full of Barry Manilow, United Fruit Company and Iron Butterfly titles whose vinyl originals now repose in thrift store bins and moldy dumpsters across America. Yet over the years the charts (i.e. consumers) have proven to be a remarkably reliable way of tracking superior work -- mainly because great rock has often also been successful rock. When Rolling Stone magazine editors recently named the 500 greatest albums of all time, nine of the magazine's first 10 choices had peaked inside Billboard's top 10. (The lone exception was the Clash's "London Calling," which only reached as high as No. 27.)

That's why, for me, Dec. 20, 1969, represents rock's summit:

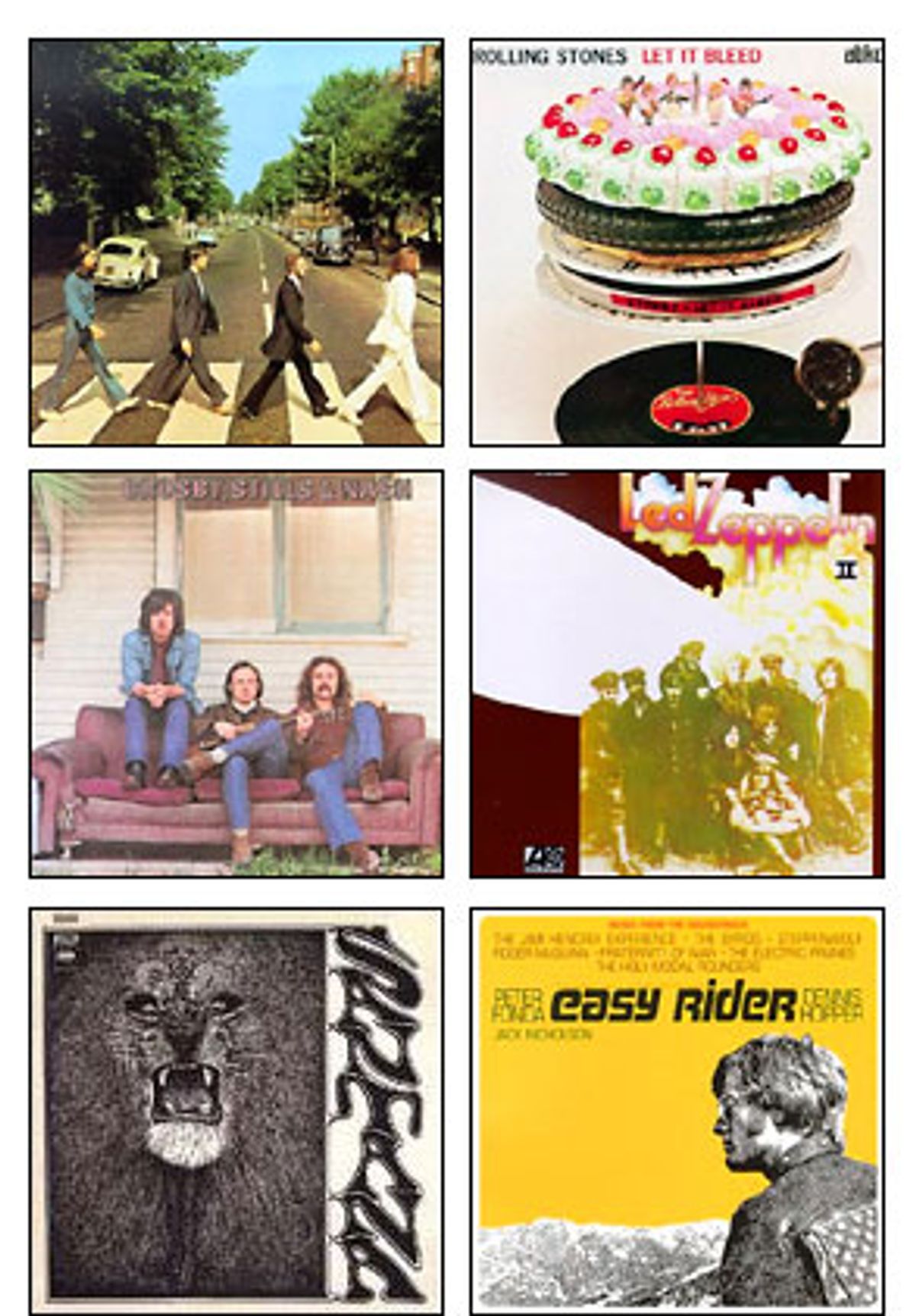

No. 1, "Abbey Road," the Beatles

No. 2, "Led Zeppelin II," Led Zeppelin

No. 3, "Tom Jones Live in Las Vegas," Tom Jones

No. 4, "Green River," Creedence Clearwater Revival

No. 5, "Let It Bleed," the Rolling Stones

No. 6, "Santana," Santana

No. 7, "Puzzle People," the Temptations

No. 8, "Blood Sweat & Tears," Blood Sweat & Tears

No. 9, "Crosby, Stills & Nash," Crosby, Stills & Nash

No. 10, "Easy Rider" soundtrack (featuring the Byrds, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and Steppenwolf)

Simply having three masterpieces together in the same week -- the Beatles' final studio gem, "Abbey Road," the revolutionary heavy-metal precursor "Led Zeppelin II," and the Stones' audacious, apocalyptic "Let It Bleed" -- would be enough to mark Dec. 20, 1969 as a special chart entry. (All right, I know Led Zeppelin isn't quite in the same league as the Beatles and the Stones, and I already hear the shrieks that C,S & N was the week's third masterpiece. But I am paying for this microphone, Mr. Green.)

But add in the historic debuts by Latin-rock guitar virtuoso Carlos Santana and the tight, high harmonies of CS&N, a classic Creedence album from a quintessential American band at its creative and commercial peak, a daring new "psychedelic soul" offering from the greatest male vocal group of all time, the Temptations, a groundbreaking movie soundtrack, jazz-rock pioneers Blood Sweat & Tears, and pop powerhouse Tom Jones, and you get a week in rock that's gone unmatched since.

Soft spots in the lineup? Some people might point to Jones, the sweaty pop swinger, or Blood Sweat & Tears. But I think they're worthy entries, although they bring up the all-star week's rear. There's something authentic and enduring about Jones' unabashed, swiveling-hips bravado. And forget the fact that middle-aged women later took to throwing their underwear at him -- the man from Wales could flat-out belt. "What's New Pussycat" still stands as one of pop's great guilty pleasures. And have you listened to "It's Not Unusual" lately?

As for Blood Sweat & Tears, the nine-piece band in '69 was arguably bigger than the Beatles, eventually selling 3 million album copies (an unheard-of tally back then) and racking up huge hits with "Spinning Wheel," "And When I Die," and "God Bless The Child." With David Clayton-Thomas' locomotive vocals and the horn section blasting out slick three-part harmonies, the Greenwich Village group captured, however fleetingly, something distinctive on that album. (The band's co-founder, Al Kooper, left before the band's meteoric rise in '69. During the week of Dec. 20, though, he was right alongside his band-mates in the top 10, playing French horn on the Stones' "You Can't Always Get What you Want" from "Let It Bleed.")

Regardless, just imagine the mix tape possibilities from that single '69 week. "Come Together," "Whole Lotta Love," "The Weight," "It's Not Unusual," "Green River," "You Can't Always Get What You Want," "Wooden Ships," "Gimme Shelter," "I Can't Get Next to You," "It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)," "Here Comes the Sun," "Evil Ways," "And When I Die," "Bad Moon Rising," "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes," and "Born to Be Wild."

Seven of the acts from that December week have been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. And if you include the appearances of the Byrds and Jimi Hendrix on the "Easy Rider" soundtrack, as well as songwriting credits by Bob Dylan and The Band's Robbie Robertson, that's 11 Hall of Famers side-by-side in one week. Not to mention some of rock's most inventive guitarists: Keith Richards, Roger McGuinn, Jimmy Page, George Harrison, Carlos Santana and, of course, Jimi Hendrix.

And just FYI, no, this week does not represent some sort of a nostalgic trip back in time for me; in Dec. '69, I had just turned 4 years old. Later, during my key record-buying years, I had no patience for backward-looking classic rock. And in high school I managed to avoid going through a Who, Zeppelin, or Doors phase. (My lone '60s/'70s indulgence was the Kinks.)

But these '69 albums have weathered time as if coated with Armor-All. If you can somehow wipe away the countless times you've heard them on monotonous classic rock radio, or being piped into the dairy aisle in your local grocery store, and you can start fresh and hear the songs on a top-flight sound system, most of the albums still crackle with excitement, 34 years later. (I'd concede, though, that portions of the "Easy Rider" soundtrack, "Blood Sweat & Tears," and "Santana" can sound a bit dated.)

Using the Billboard album chart as the benchmark, there have been other great weeks in rock history. For instance, on Sept. 4, '65, the Rolling Stones' "Out of Our Heads," the Beach Boys "Summer Days (And Summer Nights)," "Beatles VI," Dylan's "Bringing it All Back Home," and "Sinatra '65" were all bunched together in a one-of-a-kind top 10. Unfortunately, the week also featured the soundtracks to "Mary Poppins" and "The Sound of Music" -- albums, for all their undoubted virtues, that would have a hard time going mano-a-mano with "Satisfaction."

Other weeks worthy of mention include March 23, '68 (Aretha Franklin, Simon & Garfunkel, Bob Dylan ("John Wesley Harding"), the Beatles ("Magical Mystery Tour"), Smokey Robinson, Diana Ross and the Supremes and Otis Redding); Nov. 23, '74 (the Rolling Stones, John Lennon, David Bowie and Lou Reed); Sept. 8, '79 (The Knack, Supertramp, The Cars, Chic, Neil Young, the Commodores, and Led Zeppelin); Oct. 24, '92 (Garth Brooks, REM, Eric Clapton, Peter Gabriel, Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, and Mary J. Blige); Oct. 17, '98 (Jay-Z, Outkast, Tribe Called Quest, Lauryn Hill, Sheryl Crow, Kirk Franklin, and Shania Twain), and Sept. 28, 2002 (Dixie Chicks, Eminem, Nelly, Bruce Springsteen, Norah Jones, Coldplay, and James Taylor).

Using the same album-for-album chart criteria, I'd nominate Sept. 2, 1989 as the Worst Week in Rock History.

No. 1 "Repeat Offender," Richard Marx

No. 2. "Hangin' Tough," NKOTB

No. 3. "Batman" soundtrack

No. 4. "Forever Your Girl," Paula Abdul

No. 5. "Girl You Know It's True," Milli Vanilli

No. 6. "Full Moon Fever," Tom Petty

No. 7. "Skid Row" Skid Row.

No. 8. "The Raw and the Cooked," Fine Young Cannibals

No. 9. "Cuts Both Ways" Gloria Estefan

No. 10. "End of Innocence," Don Henley

The nation's collective ears must have been stuffed with wax that week (or year). You almost feel sorry for Petty, Henley and the Fine Young Cannibals, trapped forever with this rogues' gallery of career offenders. (Milli Vanilli??)

Readers may wonder why there are no contemporary charts like these -- no weeks when Radiohead, Norah Jones and Alicia Keys all rub shoulders in the top 10, without bumping into forgettable pop entries. There are several reasons why critically acclaimed rock albums charted higher in the '60s than they do now. First, there were simply fewer records released back then, so the odds of having success were better. Also, far fewer people were buying records, so it took fewer sales to hit the top 10. By the end of 1969, only 20 albums in the history of rock had ever sold 1 million copies. ("Crosby, Stills and Nash" and "Santana" were the 18th and 20th, respectively.) By contrast, this year alone nearly 50 albums sold 1 million copies or more, a difference that far outpaces the country's population gains since 1969. Also, young teens were still buying more singles than albums in 1969. That meant the demographic of heavy album buyers was concentrated among white college-age kids, giving their favorite rock acts an inside track on the Billboard charts.

But it wasn't just the individual songs and singles that made the week of Dec. 20, '69, stand out. In many ways, rock 'n' roll was the '60s -- it played a defining role in American culture that's hard even to imagine now. Listening to this music, even for those of us who didn't live through those days, summons up the extraordinary and tumultuous history of which they were such an integral part.

Screenwriter Buck Henry once reminisced to the Los Angeles Times about the summer of '69: "I had a house up above the Strip and I could look down on about a dozen houses, which all had swimming pools, and not a day went by when there weren't naked people in those pools. There was a lot of dope-inspired, orgiastic behavior. It was like Hollywood was this pond filled with drugs and hippie girls." (All that free love would soon have a consequence: California's no-fault divorce law went into effect Jan. 1, 1970, helping to usher in the Me Decade.)

In December 1969, that orgiastic mix of sex, drugs and spirituality spilled off the Billboard album charts. While the Beatles were urging us to "come together," Mick Jagger and the crew were busy searching for "someone we can cream on." Around the same time, roadies one day knocked on Jimmy Page's hotel room door to tell him that they were gang-banging Cynthia Plaster Caster upstairs in a bathtub of baked beans. Jimmy went up to watch, according to Stephen Davis' band biography, "Hammer of the Gods: The Led Zeppelin Saga." The boys in CS&N also overindulged: "We'd get so high," David Crosby once said of the group's early time in the studio. "I cannot tell a lie. We used to smoke a joint and snort a line before every [recording] session. That was a ritual." (As for the Stones, bassist Bill Wyman, accustomed to having groupies attend to his needs after every show, reportedly became severely depressed one night when the girls failed to show up. When someone asked him what the matter was, he despondently replied, "No birds.")

It was also a time of jarring violence that seemed to unfold with numbing regularity. Just look at this bloody newsreel covering four days in December '69:

Of course, the backdrop for the killing culture was the ongoing Vietnam War. In April 1969, U.S. troop levels there hit 543,400, the highest reached at any time during the war. By the week of Dec. 20, Nixon's "Vietnamization" policy of slowly withdrawing troops had drawn down that force to approximately 470,000. Nonetheless, by '69 American combat deaths in Vietnam topped 33,700, surpassing the U.S. death tally for Korean War.

On Dec. 1 of that year, the Selective Service conducted its first draft lottery since 1942, pulling out Ping-Pong balls at random with birth dates. The event determined the order of call for induction during calendar year 1970, that is, for registrants born between Jan. 1, 1944, and Dec. 31, 1950.

Appropriately, just as unlucky draftees were about to be shipped off, farewells were in the air on pop radio at the close of December 1969, with "Leaving On a Jet Plane" (Peter, Paul, and Mary), and "Someday We'll Be Together" (Diana Ross & The Supremes) coming in at 1 and 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. Those were sentimental expressions of hope. Sitting behind them at No. 3, though, was a song that had Vietnam on its mind, that put its stamp on the '60s at its close, but couldn't be bothered with sentimentality -- Creedence Clearwater Revival's pounding "Fortunate Son," which stands among rock's most exhilarating 2:18.

In it, growling lead singer John Fogerty declares unabashed class warfare:

Some folks are born silver spoon in hand

Lord, don't they help themselves, oh.

But when the taxman come to the door,

Lord, the house look a like a rummage sale, yes

and undresses the Pentagon:

Some folks are born made to wave the flag,

ooh, they're red, white and blue.

And when the band plays "Hail To The Chief,"

oh, they point the cannon at you, Lord.

Fogerty, who until two years earlier was serving once a month in the Army Reserve, wrote "Fortunate Son" in 20 minutes, sitting on the edge of a bed with a legal pad in his lap. "It's a confrontation between me and Richard Nixon," he once said.

Incredibly, "Fortunate Son" doesn't even appear on "Green River," the CCR album in the top 10 for Dec. 20, '69. That's because Fogerty was so prolific, his singles and albums were beginning to pile up on the charts. (The band's first three albums each cost $2,000 to make and were recorded in one week's time.) In 1969 alone, CCR released an unheard-of three studio albums that produced not-a-note wasted classics like "Proud Mary," "Bad Moon Rising," and "Down on the Corner."

In just over 18 months the band tallied seven top 10 singles, most of them with B-side winners to boot. Like Elvis in '56, the Beatles in '64, the Bee Gees in '78 and Michael Jackson in '83, CCR, with its mixture of Southern Creole styles and tight rockabilly touch,owned American pop music in '69. As Rob Sheffield put it in Rolling Stone, "for a year or two there, Creedence were as great as any rock & roll band could ever be."

At the same time, the Rolling Stones also found themselves in a wicked groove. Rebounding from the psychedelic mess of 1967's "Their Satanic Majesties Request," the band answered with "Beggar's Banquet" in '68, and then hit back even harder with "Let It Bleed." From the opening masterpiece "Gimme Shelter," which writer Greil Marcus dubbed "the greatest rock and roll recording ever made," "Let It Bleed" is soaked in addiction ("All my friends are junkies") violence, ("I'll stick my knife down your throat, baby"), more violence ("You knifed me in my dirty filthy basement"), and lament ("You can't always get what you want"). It's all wrapped around some of the sturdiest, most exhilarating songs ever put to vinyl. "THIS RECORD SHOULD BE PLAYED LOUD," the inside album sleeve commands, and millions of rock fans happily obeyed.

"No rock record, before or since, has ever so completely captured the sense of palpable dread that hung over its era," wrote Stephen Davis in his Stones book, "Old Gods Almost Dead."

"It's kind of an end-of-the-world thing," Jagger said of "Let it Bleed." "It's Apocalypse; the whole record's like that." (The best trivia tidbit: That's not Charlie Watts smacking the skins on the closing "You Can't Always Get What You Want," it's producer Jimmy Miller, the same "Mr. Jimmy" who Jagger sings about seeing at the Chelsea drugstore.)

In the fall of '69, the band, never shy about its love of money, even while playing to the Woodstock nation, faced critics' wrath for charging high prices -- $5.50 and $8.50 -- for its 13-city, 18-concert tour of the U.S. Writing in the San Francisco Chronicle, respected music scribe Ralph J. Gleason complained, "Can the Rolling Stones actually need all that money?"

At a Beverly Hills Wilshire Hotel press conference, Jagger fended off the criticism by suggesting the band might play a free thank-you show at the conclusion of the tour. Or, as the band's promoter later told the New York Times, "It's a Christmas and Hanukkah gift from the Stones to American youth."

That "gift," fittingly for this "Let it Bleed" moment in rock history, turned out to be Altamont.

With their new '69 album "Puzzle People," the Temptations were offering up a different kind of gift intended for black America. The greatest male vocal group of all time ("My Girl," "Get Ready," "Ain't too Proud to Beg," "Just My Imagination"), the Temps were a testament to the polished Motown sound that helped define the decade. By '69 though, the group was staking out new territory. Yes, the albums boasted the prerequisite fireball single, the R&B smash "Can't Get Next to You" that crossed over to No. 1 on the pop charts. But two years before Motown icon Marvin Gaye tackled social issues with his breakthrough release, "What's Goin' On," the Temps took a hard look around. On "Puzzle People," gone from the album cover photo was the trademark Motown matching suits. Instead, it was the Temps in afros, psychedelic shirts and smart street suits, hanging out on the stoop of a inner-city building, far away from the safe supper clubs they often played. "Puzzle People" was part of the Temps' "psychedelic soul" phase, which began earlier that year with the release of the "Cloud Nine" album.

Politically, the "Puzzle People" highlight was "Message From a Black Man": "Your eyes are open but you refuse to see/The laws of society were made for both you and me." It was the Temps' answer to James Brown's anthem, "Say It Out (I'm Black and I'm Proud)."

The timing was dead-on: On Dec. 20, 1969, in the wake of the Black Panther slayings, Chicago's superintendent of police announced there had been "no misconduct by the police officers involved" in the raid. "Message From a Black Man" emerged as an unofficial Black Power anthem.

The Beatles came bearing a gift of their own in late '69: "Abbey Road," which reigned at No. 1 for 18 weeks in the U.K., 11 in the U.S. Unhappy with the recording of "Let it Be," which was actually released after "Abbey Road," the world's most famous rock band returned to EMI Studio No 3, Abbey Road, London NW8, in July and August of '69 for their final sessions.

For a band that was on the verge of breaking up, amid personal squabbling and broken business deals, "Abbey Road" is surprisingly bright, at times seamless, and often silly ("Maxwell's Silver Hammer," "Octopus's Garden.") Not as groundbreaking as "Rubber Soul" or "Revolver," "Abbey Road" is still a classic of pop songwriting, led by John Lennon's "Come Together," which was inspired by Timothy Leary's run at California governor (Leary's slogan was "Come together, join the party") and the hard-rocking "She's So Heavy." Side 2's suite of song fragments, with their haunting melodies and great transitions ("You Never Give Me Your Money," "Carry That Weight") is unique in the Beatles' repertory. And of course pop doesn't come much more perfect than George Harrison's unabashedly optimistic "Here Comes the Sun," written using a guitar borrowed from Eric Clapton, while sitting in his friend's garden.

As the final true track on "Abbey Road," the last album recorded by the Beatles, "The End" served as the band's good-bye to the decade and an era. And they signed off with a Paul McCartney note of unquenchable optimism: "And in the end/The love you take/Is equal to the love you make."

On Dec. 20, '69, "Abbey Road" sat at No. 1 in the U.S. At No. 2 was "Led Zeppelin II," and barreling into the '70s? the band offered a radically different take on love. Opening with the carnal "Whole Lotta Love," complete with Jimmy Page's famous guitar stutter, the song single-handedly ushered in rock's next major chapter: "Way way down inside/ I'm gonna give you my love/ I'm gonna give you every inch of my love."

Heavy metal was born. Not just the relentless, thundering sound, but the strutting, cocksure attitude that would dominate rock (often in inflated, caricatured forms) for years to come. "'Whole Lotta Love' was an emergency telegram to a new generation," wrote Davis in "Hammer of the Gods." "In its frenzy of sex, chaos, and destruction, it seemed to conjure all the chilling anxieties of the dying decade. Ironically, the song (and Led Zeppelin) didn't much appeal to the kids of the sixties, who had grown up with the Beatles, the Stones, Bob Dylan. Tired, jaded, disillusioned, they were turning towards softer sound, country rock. But their younger siblings, the high school kids, were determined to have more fun. Zed Zeppelin was really their band. For the next decade Led Zeppelin would be the unchallenged monarchs of high school parking lots all over America."

The '60s were over, literally and figuratively. And during the final week of '69, in a nice piece of symbolic symmetry, the Beatles, the quintessential '60s band, and Led Zeppelin, soon-to-be '70s rock gods, flip-flopped their No. 1 and No. 2 spots atop the Billboard album chart.

Shares