Robert Altman has been moving large casts of characters smoothly through his movies and orchestrating passages of overlapping dialogue for so long now that he has often seemed as much choreographer as director. So it's fitting that he's gotten around to making a dance movie. "The Company," filmed with members of Chicago's Joffrey Ballet, must be the least flossy movie ever made about the world of dance. Ballet and modern dance haven't been particularly well served by the movies. There was Carroll Ballard's film of the Maurice Sendak-designed "Nutcracker," but mostly there are fragments: the Roland Petit ballet that opened "White Nights," and Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gregory Hines' Twyla Tharp-choreographed duet in the same movie; and the few precious moments of Baryshnikov dancing in the otherwise appalling "The Turning Point."

That stinker was pretty typical of the way the movies have always approached high art -- with genuflection and blandishments about the discipline and sacrifice to which the artiste must submit. Who needs it? I'd have traded all of it for the moment from the 2000 "Center Stage" where the statuesque Zoe Saldana uses the point of her toe shoes to stub out a cigarette. That image from a throwaway teen movie was connected to the details of real life in a way that movies about art rarely are. Who the hell can appreciate any art if you're made to feel that becoming an artist is joining the priesthood?

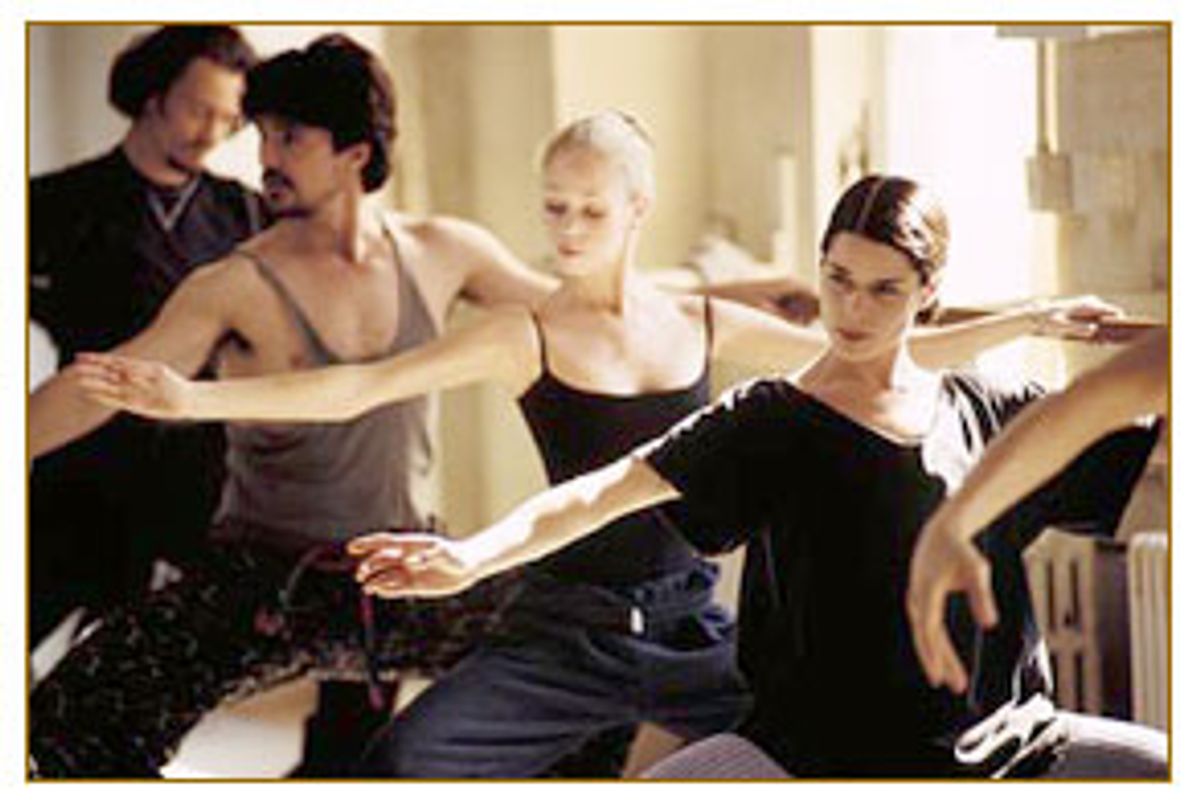

"The Company" has no more time for preachments about the nunnery of "the dahnce" than Altman's "Vincent and Theo" had for preachments about the priesthood of art. "The Company" isn't fevered and tortured the way "Vincent and Theo" was. It isn't about the agony of making art but about the pleasure of it. In this case, that pleasure is inseparable from the nearly sexual excitement of young people finding out what amazing things their bodies are capable of. Altman's movie is lighter than air, but it's also one of the most fluid expressions of his technique. You could say that it's all grace notes, but I prefer the description of my Salon colleague Stephanie Zacharek, that it's all pulses. A choreographer distills everything to movement; Altman distills the meaning of "The Company" to the movement.

Altman has never had any use for the theatrical method of introducing movie characters. It isn't surprising that he has no use for the conventions of backstage drama. The familiar plot strands in Barbara Turner's script -- the overbearing stage mother of a promising dancer, the young male dancer whose pushy mentor is jeopardizing his career, another young dancer who's shuttling from one crash pad to another -- are deliberately introduced so they can be left dangling. In conventional terms, nothing happens in "The Company." We watch the young dancers of the Joffrey rehearse, get picked (or not) for performance, fall in love, injure themselves, deal with their families, work their part-time jobs.

When a dancer snaps a tendon demonstrating a move in rehearsal, Altman doesn't do what another director would, shifting the scene to the hospital while the company breathlessly awaits news of her condition. The girl is taken away to be cared for, her replacement is chosen and rehearsals continue. That's the reality of a dance company, not some ballet equivalent of "42nd Street." Nothing happens in "The Company," but only if you consider a master director's ability to put life on-screen nothing. At moments "The Company" recalls the work of the French director Jacques Rivette, whose long, seemingly inconsequential movies give the great gift of allowing audiences to live in, and savor, each moment.

Altman has always been a weird mix of humanism and cynicism. For all his ability to plumb the contradictions of his characters, he's always been susceptible to the caricatures of the adolescent wiseass. He hits a jarring note here in the scene where a dancer relates an anecdote about a relative's recent suicide, but for the most part "The Company" is one of the most celebratory movies he's ever made. Altman seems completely seduced by the young dancers on-screen. How could he not be? At 78 he's still working with an eagerness and vigor most filmmakers never attain. In the director's statement accompanying the press kit, Altman says, "On a daily basis and in the most impossible and dramatic terms, dancers face what we all face: biological clocks and the force of gravity telling us NO. Yet for some part of their working lives dancers literally prevail over those forces. The fact that they (like the rest of us) will all ultimately be trumped by time doesn't diminish or compromise their efforts."

For years now Altman has prevailed over not just his own biological clock but the forces that want to ground any independent-minded director working in American movies. Somehow, maybe through sheer stubbornness, he's kept making movies his way. Even at its most hit-and-miss, his career represents one of the least compromised that any major filmmaker has ever managed in this country.

One of Altman's tricks has been to deceive us with characters who seem like utter fools (like Geraldine Chaplin in "Nashville") only to have them say things that are anything but foolish. Here, as the director of the Joffrey, Malcolm McDowell spouts arty little pensées. He's the essence of every "resident genius" coasting on his associations and the showy panache of his dedication to art. This is one of those guys who knew just everyone (you expect him to talk about taking tea with Pavlova), who keeps his underlings at his beck and call and slyly hands them all the problems that arise, all the while insisting that he's the man in charge.

He seems to have no idea of the nuts and bolts of a performance, always swooping in to change bits and pieces of a dance, no matter that the clock is ticking and the movements have to be set. (I attended a college with a fairly renowned dance department, and the head of the department was always wandering into rehearsals a night or two before opening, insisting on lighting changes.) It's a hilarious caricature. But at the end of one of his speeches -- the old saw about how young people today can't understand what the '60s were really like -- he says, "Thinking the movement is not becoming the movement."

That could be a summation of the way Altman has always gambled on instinct -- even here, in the midst of a movie about one of the most disciplined of arts. Altman knows when not to interfere. He allows us to observe rehearsals, the painstaking process by which phrases of movement cohere into a dance. And then, just as his movies have always done, he erases all the evidence of that work with the seeming effortlessness of the final product.

The dance sequences in "The Company" are among the most dazzling ever put on film. Altman and his cinematographer, Andrew Dunn, allow us to experience each performance from both sides of the footlights, to both watch the movement and be in it. The film opens with Alwin Nikolais' "Tensile Movement," in which the dancers move among ribbons strung out across the stage and then dance in perfect synchronization with large elastic bands framing their four splayed limbs, changing size and shape to correspond to their movements. The film ends with Robert Desrosiers' "Blue Snake," a silly, storybook extravaganza with bright colors that are pretty to look at, though the visual clutter tends to upstage the dancers.

It's a slight miscalculation because, dancewise, the movie reaches its peak midway through with the Lar Lubovitch pas de deux to Rodgers and Hart's "My Funny Valentine," played on piano and cello by Marvin Laird and Clay Ruede and danced by Neve Campbell and Joffrey dancer Domingo Rubio. I don't think it's too much to say that this is one of the most surpassingly romantic sequences ever put on film. Every cliché you've ever heard about dance being a metaphor for sublimated lovemaking might have been invented to talk about this scene.

To the accompaniment of what must be the most achingly melancholy of American standards (Altman uses different versions of the song throughout the movie, in somewhat the same way he used different versions of John Williams' theme in "The Long Goodbye"), Campbell and Rubio play out a scenario of seduction and rapture and heartache in movements that are as simple and suffused with feeling as Lorenz Hart's lyrics are. Dance, along with music and movies, is the most ephemeral of forms, and you can't help thinking of the longing that great vocalists have put into the line "Stay, little valentine, stay," as you watch the exquisite and all too fleeting beauty of this dance. Altman heightens the drama of this outdoor performance by adding the rumbling of a looming thunderstorm. It's as if God couldn't abide this moment of human perfection without adding His own complementary touch.

Altman gives this sequence the perfect coda, cutting between Rubio rehearsing alone in the studio and Campbell's Ry returning to her apartment and crying -- who knows why? Maybe because her moment of triumph is over. Whatever the reason is, Altman doesn't spell it out. What registers in the scene is seeing each dancer alone after the union they achieved onstage. The conception and editing of the sequence (by Geraldine Peroni) suggest the sequence in Jean Vigo's film "L'Atalante" where the separated newlyweds dream of embracing each other in their sleep.

Neve Campbell had previous dance experience and trained with the Joffrey for this role. She also wrote the film's story with Barbara Turner and is one of the producers. After her fine performances in "The Craft," "Wild Things" and "Panic," it shouldn't still be necessary to defend Campbell as an actress, but there are plenty of people, some of them critics, who still regard her as a "TV actress" or a teen idol. (You run into the same thing with Michelle Williams and Katie Holmes.) Campbell is no more the star here than anyone else (the title of the movie is, after all, "The Company").

She fits as beautifully into Altman's ensemble as she does among the Joffrey dancers. Her solo in "Blue Snake" is the one moment in the ballet where we're not distracted from the dancing by the design elements. Ry is the focus of the movie's preoccupation with the beauty of youth, and that particular look of Campbell's, her air of bruised expectancy, adds a touching element to the film's casual lightness. Altman doesn't use Ry, who works as a bartender in the off-season, to illustrate the difficulty of a dancer's life -- probably because at her age, having a crappy part-time job is part of what being an artist is all about. The bloom of youth is the same thing here as the bloom of creativity, the excitement of being on your own and making your own friends and choices.

There's a funny moment when a dancer who rents out space on the floor of her cramped apartment to other dancers who need places to crash goes creeping among the sleeping bodies in her living room, trying to solicit a spare condom. The lives of the dancers look pretty good to Altman, even with the disappointments and injuries, because they have the freedom to work. The struggles will come later; Altman lets them relish their ambition.

He's just as affectionate in his treatment of young love. Ry's involvement with Josh (James Franco), a young man she meets in a bar, is sketched in a series of seemingly tossed-off scenes that capture their comfortable intimacy. We don't see much more than the two of them watching TV or making breakfast or Ry coming home late from her bartending job to find Josh sacked out on the couch after preparing her a surprise New Year's Eve dinner. Here, as elsewhere in the movie, by showing us the textures of these lives instead of just the drama, Altman has made a very evocative movie. It's not until after you've seen it that the substance in the movie's lightness becomes apparent.

It's one of the mysteries of movies that directors sometimes express more of themselves and more of the themes that preoccupy them in what seems like their lightest movies. Howard Hawks never went deeper into the camaraderie of makeshift communities than he did in "Rio Bravo" and "Hatari!"; George Cukor gave the most polished demonstration of his casual elegance in "Pat and Mike"; Woody Allen finally made the serious comedy about love and death he had always wanted to in "Manhattan Murder Mystery."

"The Company" feels as light as those movies, even though it's the flip side to Altman's most turbulent film, "Vincent and Theo," which was about the agonies of the artist who defies commerce. "The Company" is about the glories of the artists who defy time. The dancers in "The Company" achieve what the racehorses in "Seabiscuit" failed to -- they express the astonishing poignancy of creatures whose strength and fragility are inseparable.

Altman, who has defied time more than any filmmaker can be expected to, is in total harmony with them. The measure of that harmony is in the recurring motif of the love affair between Campbell and Franco: The sight of the two of them mouthing to each other across crowded rooms. For a director who has always delighted in the babble of overlapping dialogue, it must have been a pleasure to find two characters who can communicate above the surrounding din.

Shares