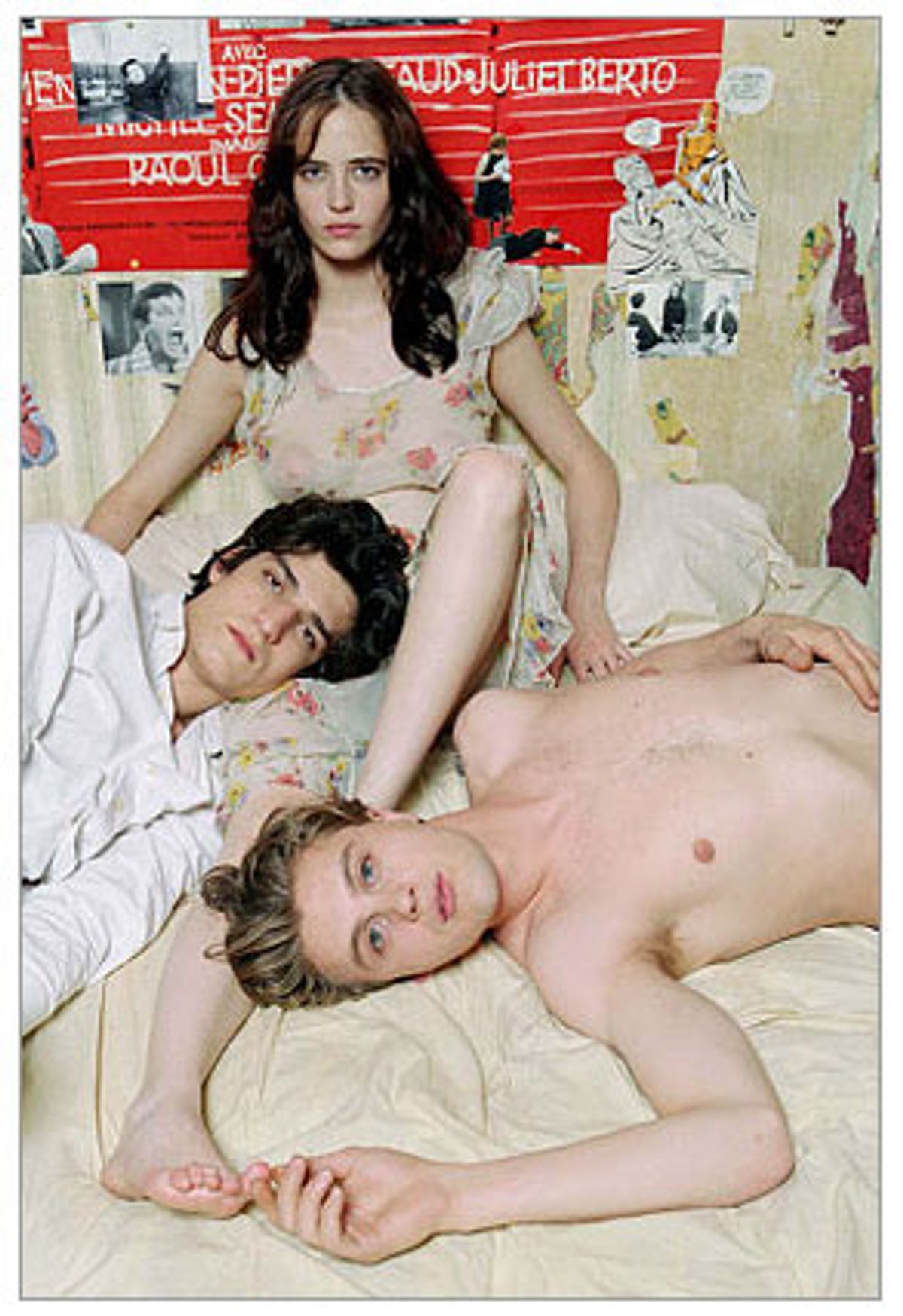

Bernardo Bertolucci's "The Dreamers" contains what may be the most startling first kiss in the movies. Matthew (Michael Pitt), a young American student trawling around Paris during the spring of 1968, is taken under the wing of Isabelle (Eva Green) and Theo (Louis Garrel), twins he's met during his nightly devotional sojourns to the Cinémathèque Française. One evening, they take Matthew home to their parents' rambling apartment for a dinner en famille. Isabelle and Theo's parents retire for the evening, leaving the three young people to themselves. Making her way to bed, Isabelle leans over to kiss Matthew goodnight, and as she does a candle flickering on the kitchen table catches her long, raven hair on fire.

The action is both dreamy and superfast. The film blurs and, for a split second, goes into slow motion, much the way our senses do in the seconds before a first kiss. Time stretches out, as it does at the approach of ecstasy or calamity. Matthew instinctively claps the flame out between his hands, Isabelle's own hands cover his, and, their faces close, they drink each other in longingly before she leans in for her kiss.

The moment is a wonderful joke, Bertolucci's equivalent of the scenes in old movies where lovers finally kiss and fireworks erupt in the sky above their heads. Matthew and Isabelle, lovers-to-be, literally spark when they first draw near each other. And yet it's anything but a joke. That one moment -- the hint of danger, the plunge of adolescent romance, the shiver of the erotic -- holds the promise of all of the movie to come. And it's a promise that Bertolucci and his fearless trio of young actors keep.

The release of "The Dreamers" in its uncut form in this country represents a triumph for Bertolucci, who, it was thought, would have to cut the film to gain an R rating. And it represents an act of real guts on the part of its distributor, Fox Searchlight (the specialty division of Twentieth Century Fox), who stood up to the kangaroo court of the MPAA ratings board and elected to accept an NC-17 classification. Whatever you think of "The Dreamers," Fox Searchlight has struck a blow for adult moviegoers in America, and honor is due it.

During the 1960 obscenity trial of "Lady Chatterley's Lover" in England, a young literary scholar named Richard Hoggart was asked on the stand if the most explicit of Lawrence's words gained anything by being printed as "f___." "Yes," he answered, "it gains a dirty suggestiveness." This surely is what would have happened to "The Dreamers" had Bertolucci been held to his contract requiring him to cut the film to earn an R rating. Real sex makes it to the screen so seldom that it is freeing to see actors allowed to do what lovers do in real life: enjoy each other's scents, juices, contours. When Michael Pitt lies with his head on Eva Green's crotch, nuzzling her pubic hair with his nose or twirling it between his fingers, you feel the bracing pleasure of having common experience acknowledged on the screen. Art isn't always about telling us what we don't know. It's also about publicly telling us what, because of politeness or our own timidity, we don't admit to knowing.

I hesitate to say that this is the most explicit film ever released by an American studio (though it is) because I don't want people flocking to "The Dreamers" expecting hot stuff. Some of the people who flocked to Bertolucci's "Last Tango in Paris" professed themselves disappointed that it wasn't as explicit as they'd expected, that it wasn't "Deep Throat." The erotics of "Last Tango" depended not just on the sex but on the willingness of Bertolucci and Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider not to hold back, their willingness to delve into the psychology of sex in all its bitterness, anger and greed, to give us the selfishness as well as the communion between these two people.

The eroticism of "The Dreamers" is of course in the sex itself, and in the lovely unself-consciousness with which Michael Pitt, Eva Green and Louis Garrel walk around in the nude. There's a charming moment when Isabelle pulls down Matthew's pants to find a snapshot of her in a bathing suit curled around his penis, and she thanks him for his gallantry in keeping her "next to his heart." But the eroticism is also in the clash of the conflicting desires being played out in the trio's games, in the adolescent bravado they use to goad each other on. "The Dreamers" isn't, like "Last Tango," about the bitterness of adult sex, the fearfulness of reaching middle age and finding desire still as strong and confusing and destructive as ever. All those emotions may lie in wait for Matthew and Isabelle and Theo when they are adults. "The Dreamers" is about sexual discovery as a drug, the moment when fantasies start to play themselves out in reality and make reality pale by comparison.

"The Dreamers" isn't a pessimistic film; it's a melancholy one -- and an elating one. This is the most playful film Bertolucci has ever made, a surprise considering the source. The screenplay for "The Dreamers" was adapted by Gilbert Adair from his 1988 novel "The Holy Innocents," a rewrite of Jean Cocteau's "Les enfants terribles" ("The Holy Terrors"). Cocteau's novel appeared in France in 1929 and was exquisitely filmed by Jean-Pierre Melville in 1949, six years before Rosamond Lehmann's English translation appeared.

Cocteau's novel is a story of the cursed enchantment of a pair of pampered, narcissistic siblings who live in their own self-created fantasy world. Luring a male friend, whom they adore and despise in equal measure, into their games, Paul and Elisabeth set themselves, their friend Gerard, and a young woman who makes them a foursome, on a course of self-destruction. There's a hothouse morbidity to both the book and Melville's film. When I saw it about 20 years ago, it made me feel as if I were gasping for air. It's both rarefied and voluptuous; it teeters on the same edge that flowers do between the time they exude their headiest perfume and the smell of corruption they give off as they rot.

Adair reset the novel in the Paris of May 1968, a few months after the tumult that followed the dismissal of the Cinémathèque's curator Henri Langlois by De Gaulle's minister of culture Andre Malraux, and at the time when student demonstrations had spiraled into a general strike, with 10 million Frenchmen, from laborers to professionals, walking off their jobs. Keyed into the elevated tone of Cocteau's poetic depravity, Adair wrote a gamier, funnier, more overtly sexual novel, which is why the tragic ending he supplied felt more like obeisance to "Les enfants terribles" than suited to the story he was telling. Bertolucci must have sensed that. He and Adair have lightened the tone of the book here, and the lightness is the key not only to why the film feels so freeing, but why it frees Bertolucci as a director. The trio's games no longer take a Sadean detour, and Matthew no longer becomes Isabelle and Theo's "martyred angel." If there's anything perverse about "The Dreamers" it's that a story of shared obsession and sexual manipulation has become bittersweet -- and it feels right that way.

Isabelle and Theo's parents having gone to the country, and Matthew having moved in, the three spend most of their time in the bourgeois warren of the family apartment, oblivious to the events outside. With movies their only true religion and the Cinémathèque still closed by order of the authorities, there is, to their minds, nowhere for them to go. So they create their own movie.

They start out enacting scenes from "Scarface" or "Blonde Venus" as part of a game they call "Name the Film." And they move on to scenes of their own devising, paid as forfeit by whoever fails at the game. With their desire to shock their American visitor, and each other, Isabelle and Theo keep raising the stakes, going about their game with the serious frivolity of children at play. Isabelle challenges Theo to masturbate in front of her and Matthew while she caresses her brother's bottom with a feather duster. (Theo kneels before a still of Dietrich in "The Blue Angel" like a penitent at prayer.) As payback, Theo challenges Matthew and Isabelle to make love in front of him. And Matthew, a kid too enraptured by his movie-fed fantasies to have made many friends, is so in love with both of them, so happy to find this sophisticated pair who share his obsessions, that he makes the mistake of thinking Isabelle and Theo regard him as an equal. (They're so umbilically joined, they even have matching strawberry birthmarks on their arms.)

The incest of the book has become mere cuddling here (Isabelle and Theo share a bed like babes in the woods), and the movie only hints that Matthew's sexual passion also extends to Theo. But those choices don't diminish the impact of what we do see and, dramatically, they don't lessen the inevitable tensions that spring up when Matthew's presence threatens the bond between the siblings. Sex is a potent force here, the most potent force -- disruptive as well as liberating. One of the most beautiful moments in the movie occurs after Matthew and Isabelle first make love and he's shocked to find that he's taken her virginity. (That Theo knew his sister was a virgin when he dared her to make love to Matthew is part of the cruelty of his challenge.) Matthew's hands covered in Isabelle's blood, he clasps her face and kisses her as if he's worshiping a goddess for her sacrifice. This is the kind of excessive romanticism that Bertolucci is capable of, the kind that can make you dizzy.

Bertolucci has long been infatuated with the sensual possibilities of decay. The apartments in "Last Tango" and "Besieged," and the apartment of "The Dreamers," a ramshackle womb, all share the same scarred wood and peeling paint. Fabio Cianchetti (who also shot "Besieged") has shot the film in warm colors, golds and dark blood-reds. This is the sensual richness you expect from Bertolucci, and it makes the trio's haven even more inviting; you're drawn into it as they are, away from the world outside. Lounging together in the bathtub, the three of them are as coolly indolent as sleeping cats.

The tensions that exist in this ménage can't help breaking the surface, because these kids live in a constant state of self-dramatization. When Isabelle says she entered the world in 1959, the year that Jean-Luc Godard's "Breathless" was released, she's saying that life didn't exist for her before the emergence of the nouvelle vague. The statement is funny because it's both true and showily self-aware. She's like a movie star delivering a line she knows will tickle her audience. Later, in one of the most startling shots, Isabelle appears in a blackened doorway, swathed below the waist in a sheet, her arms hidden in long black gloves, to become the Venus de Milo. It's a moment of great triumph for her -- turning herself into a work of art. Every role Isabelle and Theo try on is derived from the movies. They carry those images in their heads and can't resist emulating them. When Theo declaims Mao's famous remark that a revolution is not a dinner party, Bertolucci wittily frames him in front of the poster of Godard's "La Chinoise" showing Juliet Berto peeking out from behind a fort constructed of copies of Mao's little red book. Revolutionary is simply another part for Theo to play and, luckily for a movie fanatic living in Paris in 1968, one that's very chic.

At times the movie plays like a comedy of manners about the meeting between European decadence and American innocence. Matthew might almost be the movie's Daisy Miller. He's capable of being shocked, but he's not so much of a naif he's unable to protect himself. He's both drawn to Isabelle and Theo's world and able to sense what's suffocating about it. He's aware of the privilege they take for granted, and his own privilege as well. When Theo goes off on a rant about American soldiers in Vietnam, Matthew informs him that not every young American male is as lucky as he was to obtain a student deferment. Theo rather grandly proclaims that he would rather go to jail than kill people -- an easy statement for someone who doesn't have to face the draft. And when Matthew tries to dissuade Theo from hurling a Molotov cocktail at a squad of riot police, it's because he associates violence with pain. All Theo can see is himself in the role of revolutionary. Like Isabelle appearing to have chained herself to the gates of the closed Cinémathèque when she's really just wrapped the dangling chains around her wrist, Theo leaves himself the possibility of a Houdini escape when the next pose that suits him comes along. But, as themselves, they are already playing the greatest roles they will ever have.

The movie references here come thick and fast, and not just in the clips that act as pointillist illustrations of the trio's reenactments. Watching the three walk down a staircase by the river at night may remind you of the trio in "Jules and Jim" doing the same thing. And Matthew's funny and surprising dinner-table speech before his friends' astonished parents (Robin Renucci and Anna Chancellor), a reflection on a Zippo lighter as a symbol of cosmic unity, plays like Bertolucci's version of the scene in Godard's "Two or Three Things I Know About Her," where a cup of coffee is made to stand for the cosmos. When Matthew insists on taking Isabelle out for a real date -- they share a Coke at a cafe while Françoise Hardy's "Tous les garcons et les filles" plays in the background, then neck in the back row at a showing of "The Girl Can't Help It" -- the scene plays like both a parody of the movie version of '50s teenage romance and a distillation of its sweet essence.

Movie heritage is also present in Bertolucci's casting. Louis Garrel is the son of French filmmaker Philippe Garrel, and Eva Green is the niece of Marika Green, the star of Bresson's "Pickpocket." Garrel's Theo comes off as a bit too much of a Euro-brooder. He would have been better served if he were given more chances to poke fun at Theo.

Green is, I think, phenomenal, though her performance may strike some (wrongly) as overacting. Although she has appeared in a couple of Paris stage productions, this is her first movie, and starting out with Bertolucci must have been both exhilarating and terrifying for her. What she's doing here is almost reckless in its daring -- Green is an untested actress attempting not so much a stylized performance but a performance that aims to get at the core of a creature who stylizes herself. She has the type of sullen beauty that seems made for a movie camera (when you see her in a beret with a smoldering pink Sobranie dangling from her lips, you want to laugh and applaud at the rightness of it). The flicker of pride in how she presents her figure, both slim and voluptuous, for our delectation is not only assured for a young actress but integral to the character.

It's unfortunate that Bertolucci intercuts Green playing out a scene from "Queen Christina" with clips from the movie itself. The inclusion is perhaps necessary for the audience to know what's going on, but comparing a first-time actress to Garbo is a burden no one could carry off (though she acquits herself with a witty parody of Garbo's drawn-out diction). Green manages the tricky feat of balancing the knowing look in Isabelle's eyes and the knowing tone of her deep voice, with the moments when you catch a teenage girl's insecurity sneaking through. Because she plays even Isabelle's greatest affectations as a way to reveal the character, Green seems both in control and completely unprotected, a singular mixture of conscious artifice and exposed nerve endings. It's a brave performance.

Michael Pitt, the most experienced of the three young actors, has appeared in movies like "Hedwig and the Angry Inch" and "Murder by Numbers," and he's brilliant. Pitt's unusual looks, a cherub's full lips set in the unfinished face of a newborn, is the key to Matthew. He's a sensual toy for this pair, but at the same time he has too much pride to completely allow himself to be used. Pitt has a slow, just-waking-up delivery, and yet he can change moods at a quicksilver pace. He makes Matthew both green yet possessed of surprising reserves of common sense -- and good instincts. Matthew is as much spectator to Theo and Isabelle's games as participant. That's what saves him, and it's also what will eventually drive the trio apart. Pitt manages to suggest a young man who freely gives up his heart to be broken but one also strong enough not to be done in by heartbreak.

For viewers old enough to remember the events of May '68, to have taken part in them or to have watched as sympathetic observers from the rest of the world, "The Dreamers" may seem a trivialization of the politics of the time. It's true that Bertolucci and Adair are not much interested in the specifics of the issues that drove the students into the streets. (It's likely that most of the countrymen who followed them didn't much care about those issues either.) The bottom line is that the demonstrators and strikers were responding to a chance at freedom.

What Bertolucci and Adair honor in "The Dreamers" is the deliriousness that comes through in the memoirs and slogans and fiction that month inspired, a joy that not even the tear gas and beatings dispensed by the CRS, the paramilitary police anti-riot squad, could fully dissipate. A revolution that expressed itself in graffitied poetry like "All power to the imagination," "I decree the state of permanent happiness," and "Beneath the pavement, the beach," could never be fully defined or contained by any political ideology. "Shining faces" is the way British novelist Jill Neville, who was there, described the people she saw in Paris that month in her 1969 novel "The Love Germ," people who looked to her "as if they were living in the present, as if the present were no longer a wearisome assembly line that had to be hastened on and got out of the way. And in his book "Lipstick Traces," Greil Marcus described the atmosphere as this: "There was only public happiness; joy in discovering for what drama one's setting is the setting, joy in making it."

It may be offensive to veterans of the time to compare the nascent revolutionary movement that swept through France to the playacting of adolescents. But Bertolucci and Adair are teasing out a connection between their trio's sense of discovery and the sense of discovery in the streets. Had Bertolucci used "The Dreamers" to mourn a generation's lost revolutionary fervor he would have betrayed the very spirit he is honoring here. That approach could easily have seemed as if the director were using the '60s as a club with which to belittle and shame the generations that followed (as other '60s veterans have, using their memories of the '60s in the way the staid respectability of the '50s was used against them). Instead of forcing his actors to live up to unapproachable icons, Bertolucci has given them the freedom to find their own personas. (In a report on the shooting in the January issue of "Sight & Sound," Gilbert Adair writes that instead of character being the bottle actors are poured into, actors must be the vessels in which characters find their own shape.)

One of the joys of "The Dreamers" is the way that this approach frees Bertolucci. The wooziest parts of his movies have always been the ones having to do with politics. The split in the director has always been between his Marxist beliefs and his romantic-sensualist nature. In "The Last Emperor" he may have wanted us to believe that Pu Yi was happier when he was "reeducated" to be a simple gardener for Mao. But it was obvious Bertolucci's heart was in the scenes of Pu Yi's life as a decadent playboy, or tussling beneath a silk sheet with his two wives. And he may have tried to make the agrarian masses the heroes of "1900," but their toil and the fantasy triumph of these honest peasants in the film didn't look nearly as much fun as Dominique Sanda, one of the corrupt ruling class, snorting cocaine in a swank hotel room with her gay uncle.

Here, for perhaps the first time since "Before the Revolution" (made when he was only 22), Bertolucci is willing to acknowledge the discontents of political commitment. And because he's older now, he can acknowledge those discontents with affectionate humor instead of the self-critical guilt his films sometimes seemed to indulge in, as if he were chastising himself for his own political shortcomings, using film as a tool in his own revolutionary reeducation. (At those moments Bertolucci would have done well to have remembered another slogan from May '68: "Boredom is always counterrevolutionary.")

Bertolucci has been where these characters are, and that's what lets him love them. He knows that, in the young, dedication to anything -- politics or art or what have you -- goes hand in hand with narcissism and superiority. The compromises the young will have to make are, for them, inseparable from corruption. That's why Bertolucci allows some sympathy for Robin Renucci as the siblings' father, a celebrated poet who feels it is not a poet's place to sign petitions and thinks his children's belief that demonstrations will change the world is a pipe dream. He speaks in the superior tones of the literateur who has placed himself above the world. But he also knows something his kids don't, and we see his hurt when Theo tells him cruelly, "I never want to be like you." (Though in this movie, it's not the kids who lose their innocence, but the parents.)

Bertolucci realizes that to love the young, to celebrate them as he is celebrating them here, means accepting that narcissism and untested self-assurance are part of what gives them their glow. Bertolucci understands that sometimes folly is inseparable from glory. Isabelle and Theo are both worldly and naive, and Bertolucci suggests that there is something of the closed-off world they inhabit in the utopian dreams of the students and strikers passing by their windows, pulling up the cobblestones to make barricades, writing "Be Reasonable: Demand the Impossible" on walls. He's aware of the differences. (The students who got their heads bashed in by the CRS were not playacting.) But when Theo encourages Matthew to think of Mao as a film director making an epic with a cast of millions, and Matthew says he's frightened by the idea of a cast of millions acting as identical extras, all in the same uniform, chanting the same slogans, you feel that, at last, Bertolucci has freed himself from an old vexing fixation.

It's not the student masses in the street who are the heroes here, the way the peasants were in "1900," it's Isabelle and Theo, spoiled and narcissistic and casually cruel as they are, and Matthew. Their revolution may be taking place behind closed doors, but it is, however naive, however sheltered, their attempt to give all power to the imagination. When Bertolucci shows us protesters hurling Molotov cocktails, and the CRS charging in response, to the accompaniment of Edith Piaf singing "Non, je ne regrette rien," it's a moment that fuses parody and love and pride. He's linking the demonstrators to a strain of French romantic self-dramatization, and he's saying that he regrets nothing. "The Dreamers" is his tenderest film, a salute and a valentine to comrades, whether they were on the barricades or in the dark of movie theaters. To take a line from an earlier generation of French revolutionaries, he's made a dream that loves its dreamers.

Shares