On Saturday, Jan. 5, 2002, a 15-year-old boy named Charles Bishop stole a single-engine Cessna airplane from the St. Petersburg International Airport in Florida and crashed it into an office building in Tampa. The boy, who was probably mentally disturbed, died; no one else was hurt. Still, in the tense months after the 9/11 attacks, Charles Bishop's flight was one of the dozens of small, strange events that set the public imagination reeling over the horrors surrounding airplanes, and cable news shows went into overdrive to cover it. The next day on CNN, Wesley Clark, the retired Army general who was at the time the network's military analyst, was asked about "the situation in Tampa.... The fact that a teenager was able to steal this plane and crash it into a building -- what does that say about the general state of aviation security?"

"We've been worried about general aviation security for some time," Clark said. "The aircraft need to be secured, the airfields need to be secured, and obviously we're going to also have to go through and do a better job of screening who could fly aircraft, who the private pilots are, who owns these aircraft. So it's going to be another major effort."

That answer -- that pilots ought to face more-rigorous screening -- seemed logical enough; but according to some critics, Wesley Clark might have had an ulterior motive in calling for more background checks in aviation. What Clark, who is now campaigning for the Democratic presidential nomination, did not tell the CNN audience was that, months before the interview, he had been hired as a board member and lobbyist for Acxiom, an Arkansas company that manages data collected by large businesses on millions of Americans. Weeks after the Sept. 11 attacks, the company developed a computerized system that would perform instant identity checks on airline passengers. The company paid Clark -- as well as other Washington lobbyists -- to "use some of his connections to make sales calls to the government," says Jennifer Barrett, Acxiom's chief privacy officer.

Acxiom was not the only company hawking background-checking applications in the months after the Sept. 11 attacks. At the time, several information technology firms -- either out of patriotic duty or to service the bottom line -- stepped up their efforts to demonstrate the virtues of surveillance programs to officials. Government records indicate that after the attacks, ChoicePoint, the giant database firm based in Georgia, spent at least $280,000 on lobbyists who discussed background checking and the PATRIOT Act with federal officials. Another firm, EagleCheck, a small start-up in Cleveland, also met repeatedly with federal officials to promote its own airline passenger identity-checking system.

None of this is surprising; after 9/11, companies that sell data-mining systems quite naturally saw a market for their wares in Washington. What is eyebrow raising is the degree to which the government was paying attention and how quickly corporate concepts morphed into government programs.

Wesley Clark's sales calls on behalf of Acxiom offer a case in point. Before the general met with federal authorities, there's no sign that officials were contemplating using background-checking systems to secure air travel. But after months of Clark's lobbying, the government announced the creation of CAPPS II -- a passenger "prescreening" system that will perform instant background checks on everyone who flies. Although much about the government's system remains a mystery, at the broadest level it looks remarkably like Acxiom's initial plans. And Acxiom has been awarded a key contract to work on parts of the system.

Did the government's airline background-checking plan, which many prominent liberal and conservative activists say is too invasive of the flying public's privacy, have its genesis in a corporate background-checking plan? The government won't say; it has generally kept mum about the origins of CAPPS II, and officials at the Transportation Security Administration did not respond to several inquiries for more information about the origins of the plan.

But it's clear that Acxiom and other data firms actively pushed the government toward data-mining security programs, and that the government's decision to embark on CAPPS II was heavily influenced by these companies. Acxiom disputes the idea that the company is responsible for CAPPS II -- "I think they were headed there anyway," Barrett says -- but the firm acknowledges that authorities needed some guidance when it came to information technology, guidance that Acxiom was happy to provide. After the 9/11 attacks, "we felt that the government was going to need to move in a direction, much like a private sector [company] already had, toward this technology," Barrett says. "And you don't build that yourself."

To some privacy advocates Acxiom's role in CAPPS II signals the worst kind of commingling of private and public sector. A company that keeps data on millions of Americans approached the government with a plan to use that data in a way that, at least to some, resembles a vast travel surveillance program. "This may have been the most successful marketing campaign in history," says Bill Scannell, a former journalist who is now a full-time CAPPS II protester. "They came up with the product, they packaged it, and they managed to lobby to make it the government's plan. If it's true, it's so diabolical and so evil that I don't even know where to begin. You've got a company that came up with a plan to make money that directly involved messing with the U.S. Constitution and rights that the country has enjoyed for the past 200 years."

And, to further add spice to the mix, Wes Clark, on the campaign trail, has strongly criticized the PATRIOT Act and President Bush's stance on civil liberties. Lobbyist, screen thyself?

Acxiom Corp. is recognized as one of the largest "data aggregation" firms in the world, a company that makes hundreds of millions of dollars a year by collecting and categorizing information on American households. What does Acxiom know about you? Probably quite a bit. But because the firm keeps careful controls on the data it holds, Acxiom insists that it respects Americans' privacy rights.

Critics of the firm often characterize Acxiom as maintaining a giant database brimming with personal details about each of us, but executives say that, strictly speaking, that's not true. Acxiom makes most of its money by maintaining data gathered by other companies -- the world's largest banks, insurance companies, media firms, retail chains and healthcare businesses pay Acxiom to manage the information they collect on you. All of this data is not sloshing around in one shared pool, Acxiom says; Acxiom's customers, many of whom are competitors of each other, wouldn't want it that way. But Acxiom also cultivates its own collection of information on Americans, and it sells these lists to clients as a way to "enhance" their data. For instance, Acxiom keeps lists of the magazines that American households subscribe to; it can offer these lists to retail chains that want to target customers with specific products or promotions. "A golfing shop wants to know if you have an interest in golf," says Barrett, Acxiom's privacy officer. "We would append the specific variables they have selected to the data."

Barrett is careful to note that much of the data that the company keeps is sold only in lists, and not on an individualized basis. Acxiom will only tell companies which magazines they might find in a certain demographic or geographic area; you can't go to the firm if you'd like to know whether your boss gets Maxim at home. Indeed, when I asked Barrett if she could punch in my name at her office and tell me what the company could dig up on me, she said that the firm doesn't even have the technical capability to do that. It's a "misnomer that we have detailed information about customers," Barrett says. "If you subscribe to a magazine that is specific to dogs, then we might know that you have an interest in dogs -- however, it's typically not that granular. Typically it's 'I love pets.' Do I know you bought a sweater from Lands' End last night? The answer is no. That's highly proprietary information, and the companies that have that wouldn't sell it for all the money in the world."

Still, some of information that Acxiom sells is indexed on an individualized basis. These databases -- which Barrett calls "reference and risk" products -- are sold to companies and government agencies that want to look up identifying information on individuals, often to look for things like financial fraud. The databases include names, addresses, phone numbers, driver's licenses and Social Security numbers. After the 9/11 attacks, "out of curiosity we went to our reference products and we said, 'Were these people in there?'" Barrett says, referring to the hijackers. The company determined that 11 of the 19 hijackers were in its database -- and since some of them were also listed on law-enforcement watch lists or had profiles that should have raised red flags (multiple addresses or aliases, for example), Acxiom thought that its system could well have caught some of the terrorists that day.

For years, Acxiom had been using its data to help auto insurance companies check for fraud in new applications for coverage. When the company realized that it might have a future in homeland security, it decided to quickly retool the insurance-fraud system to protect the skies. "We said, 'This is not very different,'" Barrett explains. In the insurance business, "they want to know that the drivers are who they say they are -- the person hasn't lied about the fact that they have a teenager in the house who's going to drive this car." In aviation, too, there needed to be a way to determine that people were who they said they were and that they weren't lying about their backgrounds.

On Sept. 25, 2001 -- two weeks after the attacks -- Acxiom sent out a press release announcing that it was building a "security-enhancing identity verification system to help airlines quickly validate personal information supplied by their passengers." This was, Barrett notes, "before the act that created the Department of Homeland Security, and before the decision was made that security was going to be a function of the government" rather than the domain of the airline industry -- very early in the process. Still, the company wanted to let the government, the airlines and the flying public know that it was working on the problem. In the press release, Charles Morgan, Acxiom's company leader (Acxiom's term for CEO), said that "after recent tragic events, consumers seem to be in overwhelming agreement that reasonable forms of identity verification be conducted before they board airline flights." He promised that the system would protect the privacy of the flying public, and he added, "We are confident that they'll welcome the opportunity to participate in a shorter, less involved process to better ensure their safety." Acxiom believed it had the perfect way to secure air travel; all it needed now was a friendly ear in the government.

Because Acxiom's business is sensitive to many kinds of federal laws and regulations, the company has maintained an extensive lobbying presence in Washington for several years. In 2000, it created its own political action committee, and since then the Acxiom PAC has given hundreds of thousands to congressional candidates. The firm seems to have a slight preference for Democrats, but Acxiom has given money to many influential Republicans as well; in 2000, Acxiom supported both John Ashcroft (then running for reelection in the Senate), and Hillary Clinton.

But unlike some of its competitors in the data-mining business, Acxiom did not have extensive contacts with federal law enforcement and security agencies, and after 9/11, it moved quickly to cultivate those connections. Acxiom hired the Washington lobbying firm Patton Boggs, where Rodney Slater, who was Bill Clinton's second secretary of transportation, was working. Slater began to make calls for the firm in Congress (federal regulations prevented him from selling Acxiom to his former cabinet department). And Acxiom then set its eyes on Wesley Clark, the Arkansas native who was beginning his own lobbying career.

According to Acxiom representatives, officials in Clark's campaign, and others who are familiar with how Clark came to the company, the firm first offered the general a position on its board before the Sept. 11 attacks. He turned it down. But Clark had a neighbor who worked at Acxiom, and he was familiar with what the company did. After the attacks, he began unofficially talking up the company to federal authorities; after a while, the company made him another offer. Late in 2001, Clark joined the company's board and began meeting with officials on Acxiom's behalf. For his work, he earned about $500,000.

According to his lobbying records and the Center for Public Integrity, a Washington watchdog group that has investigated all the presidential candidates' corporate ties, Clark met with, among others, officials at the Justice Department, the Defense Department, the State Department, the Transportation Department, the CIA and the White House to sell them on Acxiom's screening system. The Clark campaign describes the candidate's discussions with federal officials as broad in scope, focusing on the general weaknesses in aviation security and on Acxiom's solutions to those problems. It's not clear whether, in his meetings with the government, Clark mentioned ways to address the privacy concerns with the kind of system Acxiom was proposing, though his campaign maintains that Clark has always been a strong advocate of privacy rights. In September, federal officials told Robert O'Harrow, a Washington Post reporter who was the first to report Clark's Acxiom ties, that Clark was "thoughtful and persuasive" in discussions of Acxiom's system. A follow-up story by Post reporters Ben White and R. Jeffrey Smith also reported that Clark met with Vice President Dick Cheney to discuss Acxiom: "Mr. Vice President, we know you only have a short time, and we have some very important matters to discuss," the paper quoted Clark as telling Cheney at one encounter. "So if you don't mind, I'd like to just jump into the meeting."

The Transportation Security Administration created CAPPS II late in 2002. Lockheed Martin won the main contract to work on the system; Acxiom won a subcontract under LexisNexis. Both Acxiom and LexisNexis declined to comment on the size of the contracts or the nature of the work they'll be doing for CAPPS II, referring inquiries to the government, which did not respond. (Acxiom's lobbying efforts were apparently not limited to transportation authorities. According to documents obtained by the Electronic Privacy Information Center, the firm was also well-regarded by John Poindexter's Total Information Awareness project. In an e-mail to Poindexter in May 2002, Doug Dyer, a Defense Department official, praised Acxiom for its ability to escape media scrutiny, and he said that Acxiom's officials "offered to provide help" to TIA. "Ultimately, the U.S. may need huge databases of commercial transactions that cover the world or certain areas outside the U.S.," he wrote. "Acxiom could build this mega-database.")

Clark's views on CAPPS II have been difficult to determine. Officials in his campaign said that the general had not studied the system very carefully, and they referred Salon to his comments during a Democratic presidential candidates' debate in New Hampshire on Jan. 22. In that debate, Clark was asked how his work with Acxiom fit with his criticism of the PATRIOT Act and his frequent attacks on the Bush administration's civil liberties record. "Well, I don't know about CAPPS II because I have not seen the program, and I don't think many of the people who are worried about it have," Clark said. He explained that he believes that "we need to use all of the tools and tradecraft at our disposal to help keep this country safe, and we need to do so in a way that doesn't violate people's privacy." Clark added that when he worked with Acxiom, he insisted that the company keep "a firm grip on privacy issues." If he were still working with the firm, Clark said, he'd ask the American Civil Liberties Union and other privacy advocates to "pre-approve CAPPS II": "There's nothing intrinsic in the system that we're using that can't be made fully compatible with all of the privacy concerns," he concluded.

Because Clark's opinions are murky -- and because he may one day be running against Bush, whose opinions on civil liberties are not at all murky -- some privacy advocates have been reluctant to criticize him. Peter Swire, a law professor at Ohio State University's Moritz College of Law and Bill Clinton's chief counselor for privacy in the Office of Management and Budget (a position that does not exist in the Bush administration), says that he sees no problem with Clark's work for Acxiom. "In the wake of Sept. 11 people wanted to help our country," Swire says. "At a basic level, that explains it." And Swire doesn't think it's hypocritical for the general to rail against the Bush administration's record. "Here's the difference between the Democratic candidates and the current administration: Bush wants every comma of the PATRIOT Act re-approved and he'd like to go further. The Democrats say, 'Let's do security but let's do civil liberties at the same time.' It's a little like their views on environmental regulation -- you want industry, but you want some pollution controls. You want the information society, but you want controls on the spills of personal data."

Bill Scannell, whose Web protests at Boycott Delta and Don't Spy On Us launched much of the initial concern over CAPPS II, says that initially, he too didn't mind Clark's work for Acxiom. Scannell, an ardent opponent of Bush, believed that even a lobbyist for a data-mining firm would be better on civil liberties than the current administration.

But after reading Clark's CAPPS II comments from the debate -- especially the line that there's nothing intrinsically wrong with the system -- Scannell changed his view. "If he thinks you can make an invasive program such as CAPPS II at all acceptable, if he thinks that's possible, clearly he drank too much purple Kool-Aid working for Acxiom," Scannell says. "If I were Clark's advisor I would tell him that what he needs to say -- if he believes this -- is, 'After 9/11 I wanted to help defend my country, and I come from Little Rock and the biggest data-mining company is from Little Rock, and they were saying they knew who some of the hijackers were.' He should say he went around and knocked on doors for them, but that he realized that this information was so powerful and so prone to misuse that he could never advocate using it on our people."

Unless Clark says all that, Scannell believes that "this is a man who doesn't deserve to be president."

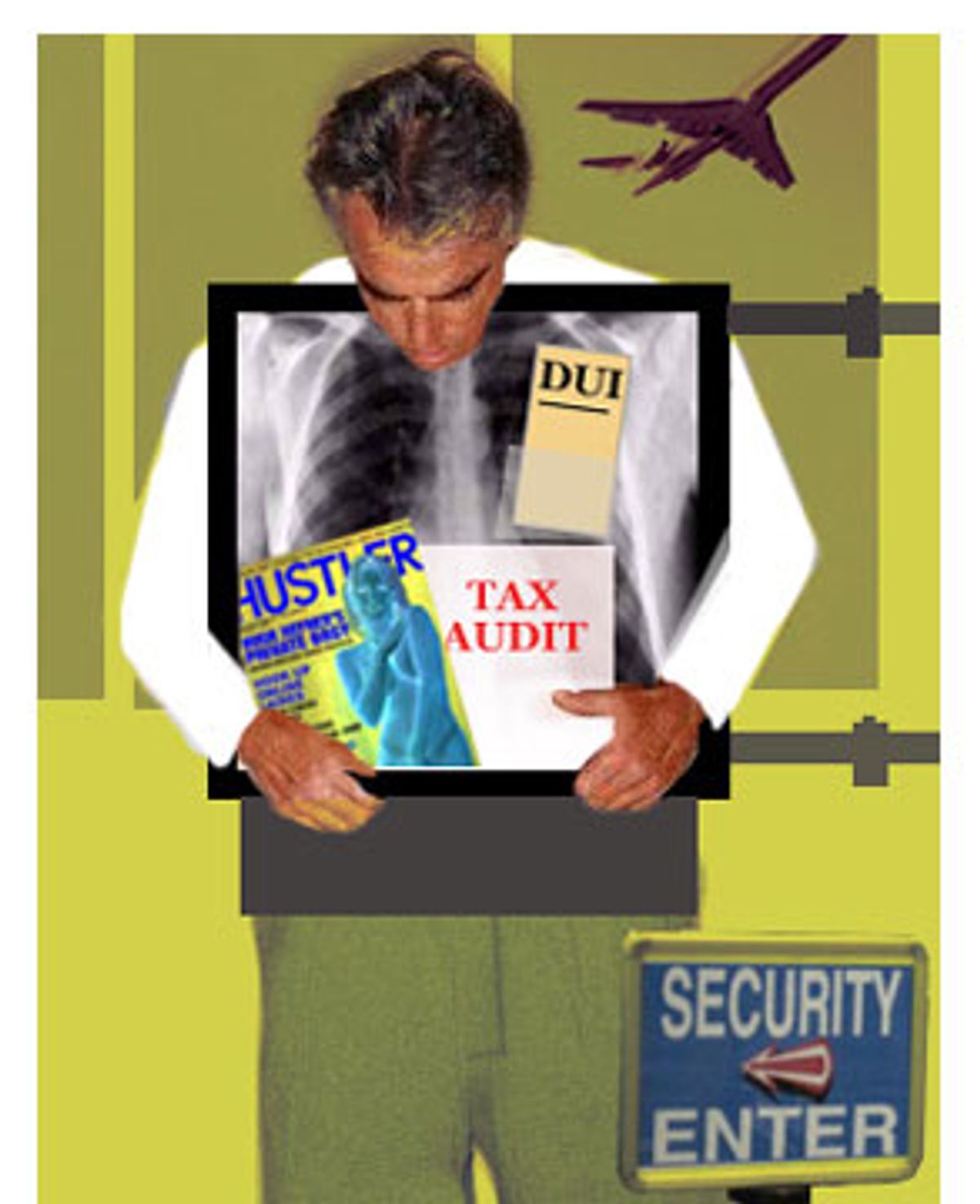

In an interview with Salon last April, Heather Rosenker, a spokeswoman for the Transportation Security Administration, described how CAPPS II, the TSA's passenger-screening system, would work. In order to make a reservation with an airline, she said, a passenger will be required to provide a name, a home address, a telephone number and a date of birth. Then, when the passenger checks into the flight, the computer will send the identifying information to commercial databases like Acxiom's to see if the passenger is "rooted in the community," Rosenker said, meaning "that you routinely are where you say you are." At the same time, the computer would check federal law enforcement databases to make sure that you aren't on a terrorist watch list or wanted for a violent crime. Depending on the results of these tests, each passenger will be given a green, yellow or red flag. Green means go. Yellow prompts more rigorous searching. Red calls in the police.

With its dependence on commercial databases to check a passenger's identity and perform quick risk assessments, CAPPS II appears almost identical to the insurance-fraud-inspired passenger-screening system Acxiom envisioned in the fall of 2001. The government's test to see if passengers are rooted in the community is the same kind of test Acxiom performs for the financial industry, and one that the company has long been saying would benefit the airlines. For instance, in a speech to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in December 2001 -- a speech attended by Ted Kennedy and James Ziglar, then the chief of the Immigration and Naturalization Service -- Jerry Jones, an Acxiom executive, declared that "technology used every day by the finance and business industries can be applied to enhance airline safety." He went on to ask why, if background checks are considered routine for insurance, they aren't used for airlines. "Because airport security today remains overly focused on finding weapons as opposed to finding terrorists," Jones answered.

The mechanism behind CAPPS II is almost completely secret; privacy advocates routinely complain that the TSA is silent on the inner workings of the system, a silence that grew so deafening by October of last year that Congress ordered the program halted until the General Accounting Office performs a rigorous study on the system. (That study is due in the middle of February.) Still, what the TSA is willing to say about CAPPS II fits exactly with what Jones outlined at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce -- CAPPS II changes the focus of the airport authorities from searching for weapons to searching for terrorists, implanting data mining at the core of transportation security. For a company like Acxiom, that has got to be a dream come true.

But Acxiom has not been the only company pushing the government toward a passenger-screening system to secure air travel. Since 2001, Jason Karosec, the CEO -- actually, "chief eagle" -- of EagleCheck, a small company in Cleveland, has also been meeting with aviation security officials to sell them on his firm's screening system, a program that he says is both more effective at catching terrorists and more respectful of privacy rights than CAPPS II. EagleCheck's system was, like Acxiom's, inspired by the 9/11 attacks. When Karosec and David Akers, his business partner, examined the records of the hijackers, they too concluded that many of the attackers might have been stopped by a computerized screening system. As the firm points out on its Web site, many of the hijackers used multiple aliases, listed different birthdays on different forms, and used stolen Social Security numbers. Some were wanted by federal authorities.

To Karosec, an engineer whose expertise is in credit-payment systems, all of this seemed like "easily catchable" stuff. "Why should people be getting in planes with fake I.D.'s?" he asks. So the company, which is funded by private investors, set to work on its system. The program that it eventually came up with is still likely to irk privacy advocates, though probably less than CAPPS II does. Instead of relying on commercial database aggregators -- like Acxiom -- Karosec says that EagleCheck would look up passengers in source databases (like your state's DMV or the federal government's electronic Social Security number database), so that no central pool of passenger data will need to be accumulated for EagleCheck. And unlike CAPPS II, EagleCheck would not rely on the airlines passenger-reservation records -- instead, the system would get your data right from your driver's license, which you'd swipe through a reader at the airport. This way, you wouldn't have to worry about the airline keeping your information after you've flown, which is one of the major concerns with CAPPS II.

Karosec is heartened by the fact that the government actually seemed to be listening to EagleCheck in the many meetings he had with officials. Despite the differences, the more he reads about CAPPS II, Karosec says, the more it sounds just like EagleCheck. "From a societal point of view, the more CAPPS II looks like EagleCheck, the better off we all will be," he says. "So we know we've influenced them. We were in there October of 2001 meeting with them. So part of me feels vindicated. They're adopting my ideas."

As a businessperson, though, Karosec is frustrated by the government's imitation of his product, and he doesn't rule out enforcing EagleCheck's patents against the government. Because, notwithstanding its claims to protect passengers' privacy, EagleCheck was not eventually awarded a contract to work on CAPPS II.

Part of this might have had to do with its size: "We're a small company in Cleveland, Ohio, and I don't know if the government wants to hand over this project to us," Karosec says.

Far better to give it to a company with the resources to hire as a lobbyist a prominent retired general with an eye on the White House.

Editor's note: This story has been corrected since its original publication.

Shares