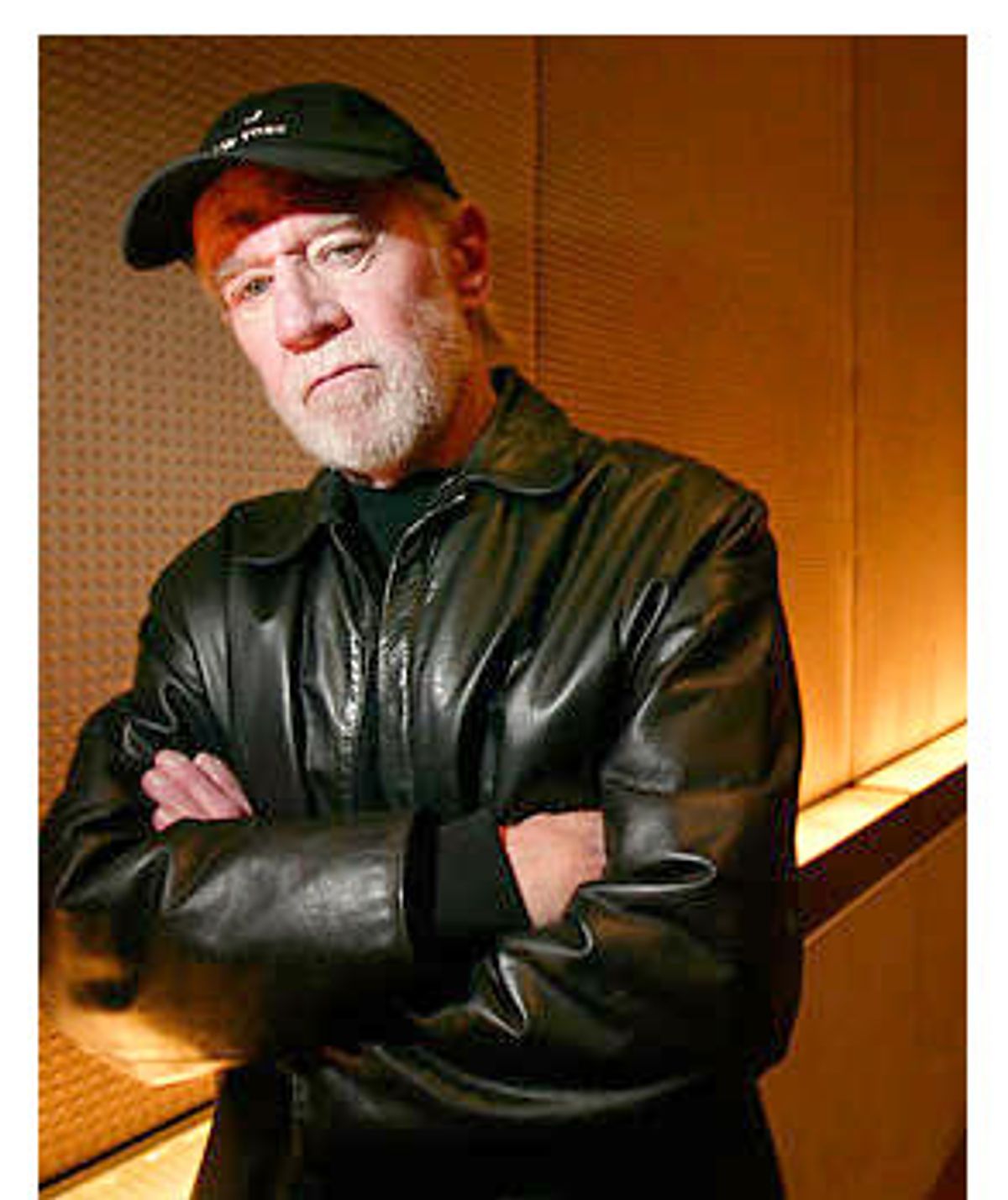

Anybody who's ever listened to George Carlin parse some absurdity of the language knows the man is a word freak. In conversation, he talks about coming from a verbal family and the need for the self-educated to prove they are as smart as the folks who actually went to college. The mere suggestion of a topic is enough to set Carlin off on monologues. But instead of feeling you're in the presence of a man who's showing off, you feel that you're listening to someone who is in love with words, with teasing out the illogic in behavior and received wisdom.

In Kevin Smith's "Jersey Girl," Carlin gives a convincing, unsentimental performance as Bart, a working-class Jersey stiff who winds up taking in his hotshot publicist son and granddaughter after his daughter-in-law dies in childbirth. For Carlin, the role was a chance to show there were more sides to him than those seen in the 90 nights a year he does stand-up. But he's very proud of the work that he's done on more than a dozen HBO specials (the next is next year) and, since he insists that his comedy comes out of his writing, of the two books he has published so far. ("When Will Jesus Bring the Pork Chops?" appears in the fall.)

As you'd expect from a man whose work received some unwanted attention back in the 1970s from the government (a father heard Carlin's "Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television" on the car radio with his son in attendance and the resulting case was argued to the Supreme Court. Here's a hint: Free speech didn't win) Carlin has plenty to say about the FCC's latest follies (call it The Pro Bowdlerizer's Tour), as well as the political impulse behind it, the tyranny of boomer parenthood, the source of his own comedy, and at least a half-dozen more issues.

Salon reached Carlin by phone during his tour to promote "Jersey Girl."

You've been in the news indirectly with the FCC fracas and people have harked back to the "Seven Words" case --

Thanks for saying "harked." So many people say "harkened back." I give you a medal.

Thanks. What I wanted to ask you is, Do you think things are worse now, are these things cyclical, is it because we're in an election year?

There are suggestions in that series of choices you gave me. Definitely, I see the need for them to secure not just the vote of the far right. As you probably know, [Bush] disappointed a lot of the far-right people with their spending and their deficits, not living up to the full conservative image they had of him. There's a need on the right, not just to get them to vote for him, but to get them to work for the ticket. And the Massachusetts Supreme Court threw the gay marriage thing in his lap as a gift.

I don't know how it works, maybe they say to the FCC, keep an eye out on things, or maybe they just wait for the Janet Jackson thing. The other answer is, yes, there is a cyclical nature to some of this. It's like being in the Air Force or the Army and having inspection. You're in a permanent outfit and everyone does their job well, so discipline gets a little lax. And then every now and then, a general or a colonel or someone will notice and suddenly there are inspections. They want your shoes shined, your coat hangers in a certain way, they want the hospital corners on the bed. They get very chickenshit for about a month. And that goes away. It's similar to that. It's a chickenshit thing that comes and goes.

But overall, the impact of John Ashcroft and the PATRIOT Act -- the impulse to want to control behavior better among the populace, and to legislate patriotism and religiosity -- has created a chilling effect on expression. And I'm sure there are people censoring themselves at these networks and all these media outlets. And it's not a long leap between that and someone saying, "You know, these left wingers, they're starting to say things that are really not in the interest of this country and perhaps they ought to be controlled, too." From dirty language to political speech doesn't seem so far of a leap once you get people used to the idea that a government body can do this.

How do these people get away with the idea that they are protecting kids?

I think in terms of the dirty language and the overprotection of children in general -- God, you need a helmet for everything these days. I have never seen any sort of study or even an informal body of opinion that thinks these words alone are somehow morally corrupting, that the words do any damage. What they do in many cases is they have a potential of embarrassing the parents because they know they don't want their kids to say them in front of the neighbors. I don't know that there's ever been any evidence shown that that father in the car who reported the "Seven Dirty Words" -- by the way, that name was what the L.A. Times called it, I never used the word "dirty," I called it "Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television" and I didn't like them called dirty because that was my argument: that they weren't. But anyway, they are now. So that father and that son sat there. I believe he belonged to something called Morals in Media. They didn't turn that off. They weren't appalled. They weren't shocked into turning the radio off or changing the station. He let the child listen, and he listened, and my assumption is that neither of the two were morally corrupted or injured in any way by this experience. They were actually exposed to the words and what damage did they do?

When my little girl was growing up, we cursed around our house and she heard me curse. She was 9 years old when the "Seven Dirty Words," so-called, case hit. We told her, "Listen, Kelly, we don't mind you using that kind of language among people who don't mind you using that kind of language. But you go to someone else's house and you're not sure how that mother or father feels, and most of them won't like it, that's not where you say it. You don't go there and insult other people and violate their own rules that they have. You're at school or in a setting where that language isn't called for or accepted, you honor what's going on there. But there's nothing wrong with the words. They're fine. They will not hurt and neither will the things they represent, which you'll find out more about later."

We have to remember what most of this springs from is religion. Probably among humans there is a natural and an innate modesty. In northern climates you were forced to cover certain parts of your body because it was cold as a motherfucker. But the church took what may have been a natural modesty about the bedroom, and a natural sort of a shyness, and exploited it into this idea that the body is somehow dirty and evil or at least potentially evil. Well, of course, you can raise a stick and kill somebody. The body is capable of all sorts of nastiness. Two of the most irresistible urges in nature -- "I gotta take a shit!" "I gotta get laid one of these days!" I know it's imperfect and it won't look great in print. But those two things are bodily needs. Sure, shit is nasty and dirty but so are a lot of other things, so is the garbage that comes out of the bottom of a grease trap in the kitchen. But the church has over the centuries has given us guilt, fear and shame about our bodies and the things that they do.

In a recent interview, you said you were anxious to take the role of Bart [in "Jersey Girl"] because you wanted to show you were capable of more things than people thought. I don't know how many people remember that you played a gay man in "The Prince of Tides." What do you think the image of you is versus what you can do?

I don't worry about my image that much. The movie people are very unaware of my career and the success of my stand-up, month in, month out and year after year. They sort of know it but they don't really. So they think of me as a kind of comedian, and I am that. But they think of me one-dimensionally and haven't really listened or heard or the seen the fact that there are a lot of things going on in my comedy besides just showing up and doing superficial jokes.

So I've tried to show that I have other sides to me besides what they see on a stage, which is a highly intensified, theatricalized, strident, confrontational thing that some people read as anger. They don't see me as a person with a well-rounded personality. Granted, "The Prince of Tides" was a great exception. Everything else I've been offered and not done has been very cartoony and one-dimensional -- you're the high-school principal and the kids get the better of you and your temper explodes. But because I cared to act a little, because I would like to entertain that part of myself, I wanted Hollywood people to see that I could do more. Whenever I meet a guy who makes movies I say, "If you ever need someone to kill six children, call me, because I have other things I can do."

I'm surprised people think of what you do as confrontational. My idea of your stand-up has been that there is always something gentle about it. It starts in observational humor. I think of someone standing on stage, very wryly and very calmly, talking about absurdities.

The comedy has always been drawn from three wells. First, the English language, the interesting ways we use, abuse, and overuse certain terms and lingo and faddish trendy buzzwords and catch phrases and Americanisms. And the very common mistakes that bother me. Because I'm not formally educated. Those who are self-taught generally need to prove to the rest of the world how smart they are. We like saying, "You're saying that wrong." Especially the media, the college-educated people who are supposed to show the way ... I like catching them.

Then there's what's commonly called observational comedy, which draws on the real world of universal experience, things we all know very well and mostly agree about -- kids, pets, driving, the stores, television commercials -- all of these things that are perfectly universal and that don't create controversy when you discuss them.

And then there's what I think of as the larger world, the world of issues -- sometimes they're political issues -- that we will never all agree about and that generally will never go away: race, war, politics, government, big business, all of those institutional larger things, religion, and the interplay among them and how badly we're doing in managing these important things. This is what I've evolved to in terms of my personal way of looking at the world, which is to say, "you folks aren't doing a very good job." I've really divorced myself from it. So it's a critique of the human species and their follies, the bad choices that they've made, and in particular the so-called leader of the human species, American culture, consumer market culture that has made a lot of bad choices and let itself get to where it's now circling the drain.

So these three areas each reveal a different feeling. The first one is kind of a classroom person, a person who's clever and can show you some patterns that you didn't notice before. The observational one reveals that gentler and more vulnerable fellow. And then the third one is when I am complaining about things -- in a tone that people read as anger because it's in a large theater, it's heightened, it's intensified. There's a degree of confrontation in it because I look for the things that push people's buttons. I want people to feel uneasy at first. I want to find out the things that disturb them a little.

[I get asked] "Are you able to shock people anymore?" I never set out to shock. Shock is just an uptown version of surprise, and humor is based on surprise, so if shock is built in there, fine. So if somebody started swearing just to shock you, that's him. I use these words as ornaments and seasonings in my stew.

But taboos and bothering people and pressing their buttons and getting them a little riled up, those things are religion, God, the flag and children. Children especially as they relate to the parent-child syndrome now, this cult of parenthood, the cult of the child, this terrible boomer manifestation of their self-regard by wanting to make their children perfect. Because their children are, after all, genetically them. They didn't get it quite all right, so they want to make perfect children. And when I talk about these people there is a definite feeling in me of disdain and dissatisfaction.

When people say, "What are you so angry about?" Well, that's a terrible oversimplification because I don't live an angry life as people who know me for five minutes or five years will say. They rarely see me in an angry mood. I get irritated like anyone else, in traffic or in a long line that's not moving. But I don't carry anger around. What I feel is a sense of betrayal by my species and by my culture -- that they lost their way and misled me, too, to a degree.

I'm a disappointed idealist. I think of myself as a skeptic, a realist. I think the cynics are the people who left the gas tank on the Ford Pinto, companies that kill people and just cross them out because they can't afford to retool. That's a cynical position. But the saying goes, if you scratch a cynic, you find a disappointed idealist, and that's what's going on with me. Down deep and underneath, the flame still flickers. I wish for an idealist, utopic world but the realist in me says it's never gonna happen because of the way they've structured power and money and control and the hierarchies they've established.

Bart is a guy who could have been easily played as the lovable old codger. You've kept some nice rough edges on him.

First of all, when Kevin told me he wrote this in my voice, I knew that this fellow inhabited me somewhere. I would have loved to have been a trained actor from, say, mid-adolescence -- learn the craft, learn the traditions, work in stock, work all the classics, work with well-trained actors and really develop. Lacking that, I find that I have, in my observational life -- because I am smart, and I do retain well -- a lot of colors in my paint box. I know something about Eastern, blue-collar men who hang around, more or less neighborhood guys. I mean, I know from them just absorbing them. From the initial stuff about looking at the character, I write a little back story so that I know he has a history of things that has made him the way he is now.

I was amused to see you playing a priest in "Dogma" because didn't you have a run-in with Cardinal Cushing when you were a DJ in Boston?

I was at WEZE. I came from a Top 40 station and went to Boston for the allure of the larger market, and my friend who had become the station manager, an older gentleman who liked me and knew my mother and tried to look out for me a little when I was a young DJ, brought me on board with him when he went there. I went there knowing that it was an NBC station. The music they played at night was all like Keely Smith, Frank Sinatra, Nelson Riddle. Daytime they had soap opera, and fairly straightforward middle-of-the-road programming.

So one of the things they had was the rosary live led by Cardinal Cushing, this much larger-than-life figure. He, of course, was this almost mythical and legendary figure and powerful and [lowers his voice to the texture of slowly rolling gravel] he had that voice.

A voice you never forgot.

... Almost as if it were coming through the clouds. So he led that rosary each night for 15 minutes from 6:45 until 7 p.m., and I was the board announcer. I'd interject a commercial or a station break here or there and I'd essentially turn the knobs and dials and bring in the network and bring [the cardinal] in, he was on a remote, he was somewhere across town.

Well, this particular night he was doing the sorrowful mysteries [gravel voice again], "the five sorrowful mysteries. Hail Mary ..." and the nuns would answer. It always timed out very well. Seven o'clock he was finished and he closed it out, and then you went to "NBC News on the Hour." And it was either sponsored or faded. The sponsored ones were more important to be sure you got 'em in, and that night it was Alka-Seltzer. And I'm sitting there at the board and he is running long because he started the 15 minutes giving a rambling speech about the Little Sisters of the Poor. [Gravel voice mumbling about the orphans and the old people] So he started late and by the time five seconds before 7 o'clock rolled around he's only in the middle of the fifth sorrowful mystery.

So I went just to the network, "NBC News brought to you by Alka-Seltzer." So within two or three minutes he was on the phone and I was the only one there, and I answered the phones and he said [gravel voice again] "I'd like to speak to the young man that turned off the holy word of God." And I said, "Well, that was me, Cardinal Cushing." I hid behind the government. I said, "I have a program log I have to follow, the FCC, and I'm bound by the law to follow this log" -- I was, at the time, 22 years old -- "and if I don't follow it I can get in trouble because I have to sign off that these things got done. That was a sponsored newscast. My job would be at risk." I told him, "Of course, I hope you'll speak to the station manager." And the station manager backed me up. I'm sure he was full of apologies but he backed me up. So that was just a wonderful moment and a harbinger perhaps of future run-ins with religious authorities.

NBC got a call from the New York archbishop's office while you were hosting the first ever "Saturday Night Live," didn't they?

Before we were off the air, that's how the legend goes. Part of what I was doing at that time was a thing called "God Is Not Perfect." My argument was, "Look, he can't make two fingerprints the same. He can't make two leaves. Take a look at two leaves -- no two of them are alike. This is not good. Look at a mountain range, they're all crooked." So it's clearly satire, it's clearly an absurdist thing, and the story goes, the chancery was on the phone before we off the air. We were all kind of proud of that.

Thanks for talking to us.

I want a final sentence: All you folks who've read and come this far, I'm much more coherent and articulate when I have a fuckin' keyboard in front of me. Gimme a break, I was on the phone!

Shares