I had never stopped to read a James De La Vega chalking until the spring of 2000, while I was on the way to the 92nd Street Y where I work out. It was a warm day, and I was already wearing sandals. I looked down and saw a picture of a little bird, chirping. I moved to my left to find the beginning of the sentence and read: THIS MOMENT IS MORE PRECIOUS THAN YOU THINK. I had been feeling melancholy that morning and this aphorism was an articulation of my very thought.

A few weeks later, I finally tracked down De La Vega in his small glass-encased studio on 103rd Street in Spanish Harlem to ask him about his work. The chalkings had brought me to him, and he was pleased, because this is another of his pursuits, reaching out to people who live below the interface, the invisible line at 96th Street that separates Spanish Harlem, El Barrio, from the rest of New York.

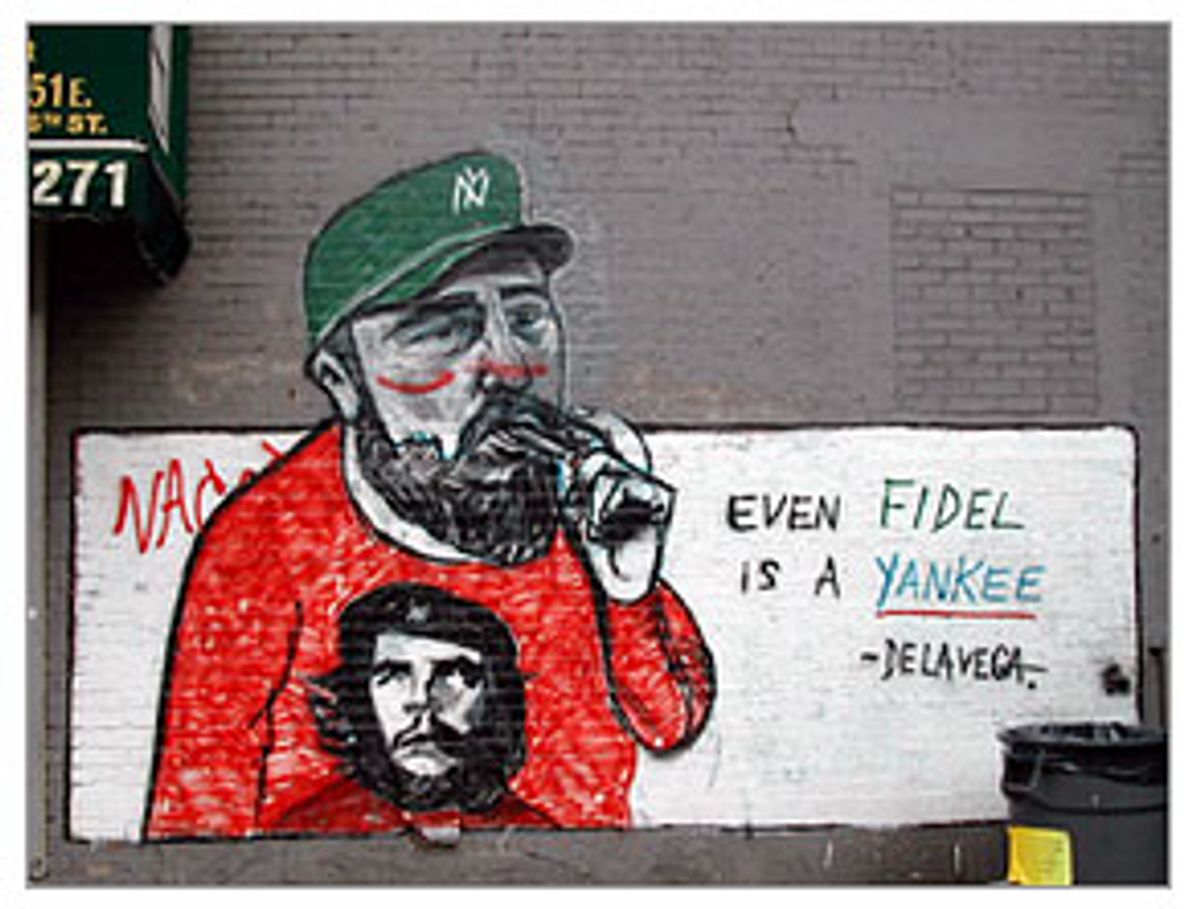

De La Vega's chalkings and murals make him probably the most revered street artist in New York; the chalkings can be found all over the city but mostly in front of subway stations and on well-traveled streets. But they may not be there for long. Last week, De La Vega entered a not guilty plea on a charge of intentionally defacing public property, after he was arrested last July 17 while working on a mural on the side of a Bronx warehouse. He was reportedly offered a 30-day jail sentence in return for a guilty plea, but instead, on June 9, he will be a defendant in the Bronx Criminal Court to challenge New York City's "graffiti laws," passed in the early 1970s during Mayor John Lindsay's administration, which made painting on a wall an act of vandalism. The graffiti task force Lindsay set up is still in operation, and De La Vega has been charged under a law that reads in part: "No person shall write, paint or draw any inscription, figure or mark of any type on any public or private building ... pursuant to a franchise, concession or revocable consent granted by the city, unless the express permission of the owner or operator of the property has been obtained."

De La Vega, 32, was arrested once before, in 1999, as he was painting the wall of the Associate Foods Supermarket near his gallery. Two hours after he pleaded guilty, the owner of the supermarket, Euripides Reynoso, came to his defense, saying he had been given permission for the painting, but it was too late -- De La Vega was found guilty and given probation. "I plan to call Mr. Reynoso as a defense witness during the trial in June," says De La Vega's attorney, Kenneth Gilbert, of the nonprofit Neighborhood Defenders. "And there are many others who love James De La Vega and his work if the judge will allow them time to speak." Meanwhile, Robert Johnson, the Bronx district attorney, recently told the New York Times, "We find it offensive that people come here and treat our walls as their canvas."

After the plea hearing, De La Vega said, "I could not admit to intentionally damaging property. I did not think of the wall as private property; it is a wall of art. For years it has always been filled with graffiti. I added to it. My intent was to share my art in the hopes of bringing a smile or a thought to the commuters stopped at the traffic light at a busy intersection in the Bronx."

So now De La Vega will face the court with the possibility of up to a year of jail time. It will also put him at a much higher risk of a tougher sentence if he continues making street art when he is released. And it's a particularly dangerous moment for an artist who has seemed to be close to the brink of widespread success, a Basquiat to be, but who has yet to commercially break out of the East Harlem community he stays loyal to.

Not that his art is contained there. On any given morning, De La Vega will go out early and choose a location and an aphorism that suits his mood, selecting from 150 or so he has stored in his head. Some of them are quotations; others are stirred by his reading. When I first met him, he was reading the poems of Pablo Neruda. A well-worn Bible is frequently at his side; Ecclesiastes is a particular inspiration.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

De La Vega had a new chalking in his head on that first warm spring day I visited his studio. He felt trapped inside, unable to open the floor-to-ceiling glass windows, and there was no air conditioning, so we spilled out onto the street, a fruit stall on one corner, a communal garden in the middle of the block, and as people passed, they greeted James and he greeted them. Many know him as a prominent man in the community, someone with gravitas, despite his youth.

We crossed the street in search of a smoother sidewalk and then, without saying another word, he bent down and began his drawing. It was abstract, a series of geometrical and morphed forms one on top of the other, like a series of acrobats climbing on each other's shoulders at the circus. I stood at a distance and watched the drawing take shape, moving with James upward and away from Third to Lexington Avenue, and then he suddenly stopped and signed "De La Vega" at the bottom. The drawing was playful, and also mysterious. I asked a passerby what he thought it meant and he said, as though it were the most obvious lesson in the world: "Life must be in balance." The communication between the artist and his neighbors seemed as kinetic as the drawings.

De La Vega painted his first wall portrait in 1993 after a teenage drug dealer he knew was killed. "Sam's family asked me to paint a memorial for him on a public wall on 102nd Street," he explains. "It was my gift to the neighborhood, to the parents. People stopped by to watch me paint and I realized, this is where I belong, out on the street making art." Tragedy has touched his life, as it has touched a lot of the young men raised in El Barrio. De La Vega's father died of AIDS in 1989. And although his younger brother is doing well now, he once belonged to a gang. Men and boys he knew and loved have fallen dead, but he has resurrected them through his portraits, painted boldly on the bricks of the neighborhood, giving the walls new life. "The walls breathe again," he has said.

Unlike the chalkings or wall paintings, which feel easier to render and loosen him, the portraits and paintings he makes in the studio are a discipline. They are mostly self-portraits or portraits of his mother, Elsie Matos -- she is ubiquitous in his work -- or his daughter, or other family members, or political leaders. Some of the paintings are lightly stenciled, playful and light; others are volcanic and dense. He only uses acrylic, which he applies with thick brushes and a palette knife. These dense paintings are often disturbing, particularly the self-portraits. And this is puzzling; De La Vega has beautiful, near-perfect teeth, and his smile is broad and engaging. He is soft-spoken and thoughtful, with the manners of a gentleman.

"It's the animal in me," De La Vega explains. "The animal in all of us that I paint."

Not many sons and daughters of El Barrio -- or any other barrio -- escape the hardships of the community and then return by choice. A graduate of Cornell (he received an MFA in 1994), De La Vega has done this, consciously and purposively. Although he lives in the Bronx, he returns every morning to his studio, which is also a gallery, in El Barrio. He does not consider living in the Bronx a defection, explaining that he requires distance to work. His mother, stepfather and brother still live in the apartment where he grew up. His 2-year-old daughter and her mother, a former girlfriend, live nearby.

How can an artist like James De La Vega break out of El Barrio? And does it matter, apart from the obvious financial reasons, if he doesn't? Those were the questions that held me throughout the weeks I interviewed him in Spanish Harlem.

"You're asking the wrong questions. You should be asking why the art galleries aren't picking James up," says Yazmin Ramirez, consulting curator at El Museo del Barrio. "Why have they suddenly lost interest in vanguard artists? In the '80s, he would have been picked up in a second."

Most agree that De La Vega has great talent. The pop painter LeRoy Neiman has become one of De La Vega's advisors (they serendipitously met in a restaurant some years ago) and attends all his shows. Neiman seems unconcerned that De La Vega has not had a major gallery opening downtown, and pooh-poohs thoughts that De La Vega could somehow be managing his career more wisely. "He doesn't need an agent. He's a crackerjack and has a big talent. He's deserving and he'll make it," Neiman says.

De La Vega's studio is next to a flower shop on 104th Street and Lexington Avenue, across the street from the schoolyard of P.S. 72, which has become his outdoor gallery. He organizes shows there at least twice a year, not only for his own work but for that of other artists in El Barrio as well. The work hangs from the fences or leans against the walls. The gatherings are always gala events, drawing many from the community and still too few from outside.

On a day that I stopped by, his mother, his muse, also dropped in with some lunch for De La Vega and a bag of plums from the market. "Still feeding your son," I said facetiously, and she smiled broadly, maternally offering me a plum as well.

"She's the main woman in my life," De La Vega says.

People walked in and out at a steady pace. A self-taught artist, Francisco Lopez, came by asking for advice. De La Vega looked through his portfolio and kept a piece on consignment. I thought the young man would faint from happiness.

Helping others is one of the few things that makes De La Vega smile these days. "I'm an artist, not a criminal," he told me ruefully on the telephone the other day. He sounded sad, and wondered if he'd made the right decision to plead not guilty. It was a rare moment of doubt for him, and he ended with a more positive thought: "I think of the art in this neighborhood, and my history here. People come up to me and say, I'm living in Spanish Harlem because of the art. This neighborhood was hurting before you started painting on these walls."

Shares