After finishing Ian McEwan's novel "Enduring Love" I felt that the book surely couldn't be saying what it appeared to be saying, and yet I couldn't see any other possible interpretation. Having seen Roger Michell's film of the novel, I'm relieved that someone else shared my reading of the book, and appalled to have that reading confirmed.

"Enduring Love" is the looniest bit of special pleading for the deranged since Peter Shaffer's "Equus." In that play, a teenage boy who blinds six horses with a metal spike is held up by his impotent, disillusioned psychiatrist as an exemplar of passion in a passionless world. "Enduring Love" is about how a man who is incapable of love is made a better person when he's stalked by a psychotic.

That may not be at first apparent, perhaps because Michell sucks you right into the story. The opening of "Enduring Love" has the lucidity of a very bad dream. Joe (Daniel Craig), a university lecturer, takes his live-in girlfriend Claire (Samantha Morton) on a picnic with the intent of asking her to marry him. It's a bright, cloudless day, the setting one of those impossibly green English fields. Suddenly, Claire is distracted from the question she can tell is coming by the sight of a hot-air balloon skimming the field. A young boy stands helplessly in the basket while his grandfather tries to stop it from ascending. The matter of factness with which Michell and his cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos shoot this sight gives it the quality of the truly surreal: It's concrete, undeniable, and yet you can't process it.

These moments before Joe acts to help the man and his grandson, a hesitation that feels like an eternity, are one of the most effective depictions of the intrusion of catastrophe into everyday life that I've ever seen in a movie. Other men in the field join in the rescue attempt and by a cruel twist, both grandson and grandfather are saved while one of the rescuers is killed.

The next scene, where Joe relates the ordeal over dinner to his friends Robin (the wonderful Bill Nighy) and Rachel (Susan Lynch), suggests that the movie is going to be about Joe's survivor's guilt (he believes he could have done more to prevent the disaster) and about how we are cut adrift by the sudden, absurd intrusion of death into the safety of our lives. Both the content and the rhythm of the conversation in this scene feels authentic. Robin, being honest but also trying to bolster his friend, says he himself would have been a gibbering idiot in those circumstances. But both Robin, with his admiration, and Joe, with his feelings of inadequacy, are buying into a myth of heroism, ignoring the plain truth that an unthinking competence takes over in many of us during moments of disaster. (That may help victims as well as rescuers, giving the former what assistance they need while allowing the latter to distance themselves from the horrific reality in front of them.)

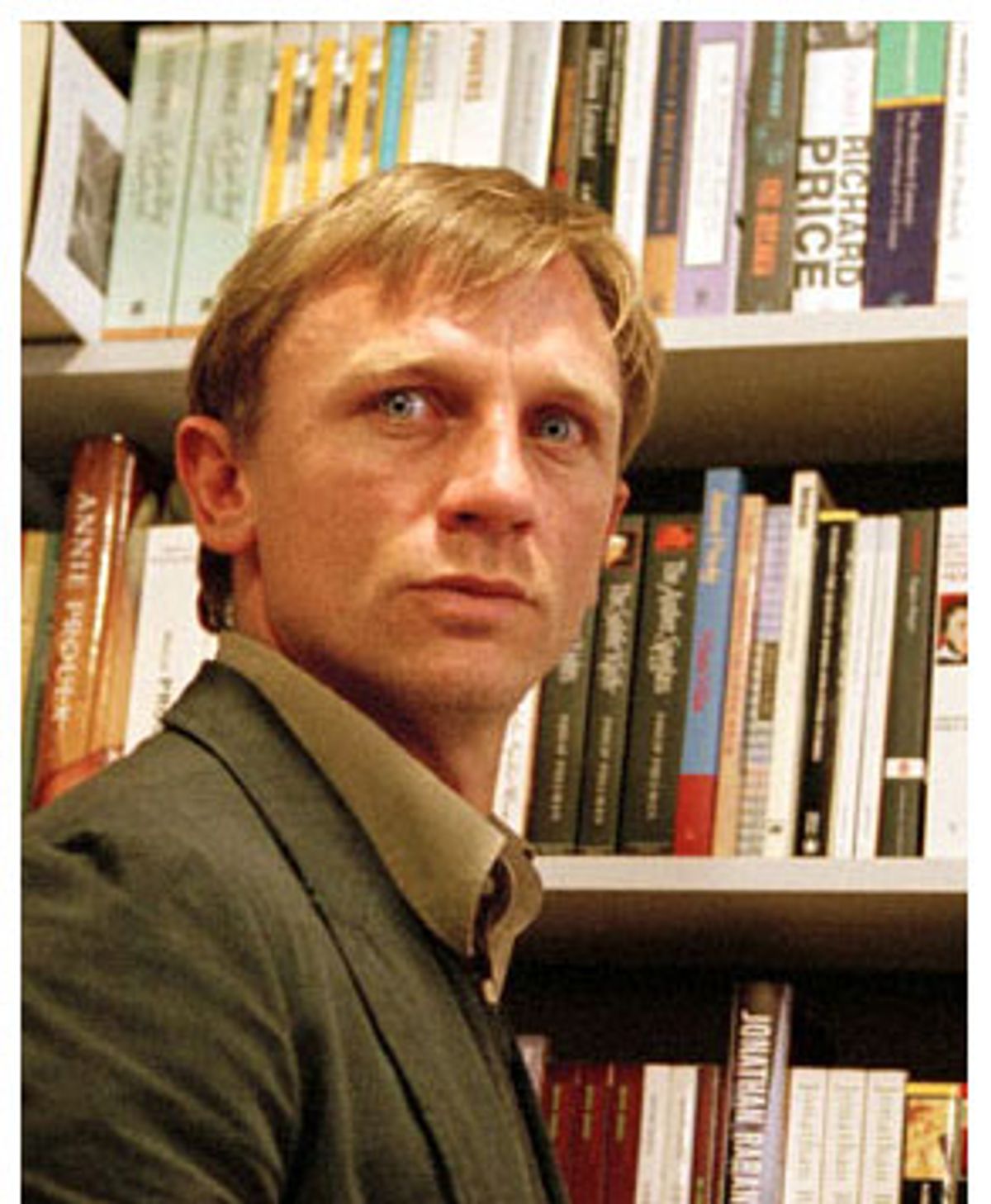

But the movie is about something else altogether. Joe gets a call from one of his fellow rescuers, wanting to meet up with him. Jed (Rhys Ifans) is a gangling, scruffy fellow whose gentle voice and timid demeanor hide a frightening certainty and intimidating persistence. At first Joe believes Jed just needs someone to talk to about their shared trauma. But Jed starts pleading with Joe, challenging him to admit to what Jed sees as a shared moment of love between them. Rightfully believing Jed to be deranged, Joe begs off, but soon Jed is shadowing him, snapping his picture while he's browsing in a bookstore, turning up in his lectures, standing in the playground across from Joe's apartment in the middle of the night.

"Enduring Love" is skillfully, if showily, made. Michell's direction doesn't have the art-installation starkness it had in his last film, "The Mother," but he still makes a spectacle of his technique. (The medium shots, in which characters are held in close-up while we peer to see what they're looking at in the blurry background become especially annoying.)

The picture is being sold as if it were a thriller, and it might be useful to look at it as if it were. Hitchcock used the derogatory name "the plausibles" to refer to the people who asked him why his characters didn't just go to the police. It's hard not to feel like one of the plausibles, though, while you're wondering why Joe doesn't report the cuckoo Jed. Granted, if the stalking laws in the U.K. are anything like they are in the U.S., the response Joe would be likely to get would be pitifully inadequate. But Joe doesn't even consider going to the cops. And even though a madman is sitting across the street watching his bedroom window through the night, nobody -- especially not Claire (Morton is, as always, believable, but wasted in a girlfriend role) -- considers this might be what's making Joe so difficult.

But if "Enduring Love" doesn't make sense as a thriller, it's equally nonsensical as the parable it wants to be. The movie raises the specter of Jed's fear of his homosexual feelings for Joe and the way he tries to pass those feelings off as religious and nonsexual. (And it should be said that Ifans is excellent in an essentially unplayable role, bringing us as close as we can come to empathy for the insane, destructive Jed. ) But neither Michell nor screenwriter Joe Penhall -- nor, I'm betting, McEwan -- probe Jed's psychology very deeply, for the same reason they don't send Joe to the cops: They want nothing to hinder Jed in his role as the movie's deus ex machina.

Several times we see Joe lecturing his classes about how love and goodness may simply be constructs human beings have devised to make our biological imperatives seem more noble than they are. At home, he's more and more distant from Claire. Joe isn't a bad person -- he doesn't kill or steal, he doesn't cheat on Claire, he pitches right into a dangerous rescue effort. We may all know somebody like Joe -- decent but cold (the distracted quality in Daniel Craig's acting plays into Joe's aloofness) -- and we may like them but not be particularly anxious to spend time with them. But a character who questions the reality of love, who wonders if goodness isn't a human construct instead of a moral value, is just the sort to bring out the combination of social worker and missionary that resides in some people. They conclude -- as the movie concludes -- that such a person must be leading an empty life. So in the movie's scheme Jed, who represents unwavering faith in love taken to a crazy extreme, is the avenging angel sent to punish the cold, analytical Joe for his inability to love.

The only reason the filmmakers get away with this scenario is that Joe is a man. Try to imagine the reaction to a movie where an independent woman was stalked by a man who insists, despite her protestations, that she is really in love with him. And imagine the reaction if the movie said she were a better person because of it, as "Enduring Love" says that Joe winds up a better, more loving man.

There are a few oases of sanity in all this. Corin Redgrave, as a witness to the accident, has one scene late in the film that delineates a survivor's guilt without the masochism that hangs over the rest of the movie. And in three brief scenes, Helen McCrory, as the widow of the man killed in the rescue attempt, demonstrates the skill she did in her one scene in "Charlotte Gray": She's so good she stops the movie dead in its tracks. She is the most effective sort of scene stealer, not one who accomplishes it by design or deviousness, but by embodying her role so fully and believably that she makes the reality of everything around her suspect.

Calling "Enduring Love" an irresponsible movie only invokes the specious argument that movies can send crazy people over the edge. I don't believe that. But I do think Ian McEwan in writing the novel, and Michell and Penhall in making this film, have been callous. Perhaps they've been lucky enough to be spared the nutters that writers and artists can attract. But you don't have to be famous to be stalked and what would any of them say, I wonder, to someone who has -- that they should open themselves up to a potential growth experience? "Enduring Love" takes the "You're not crazy, you're special" argument to a new extreme. It's affirmative action for psychos.

Shares