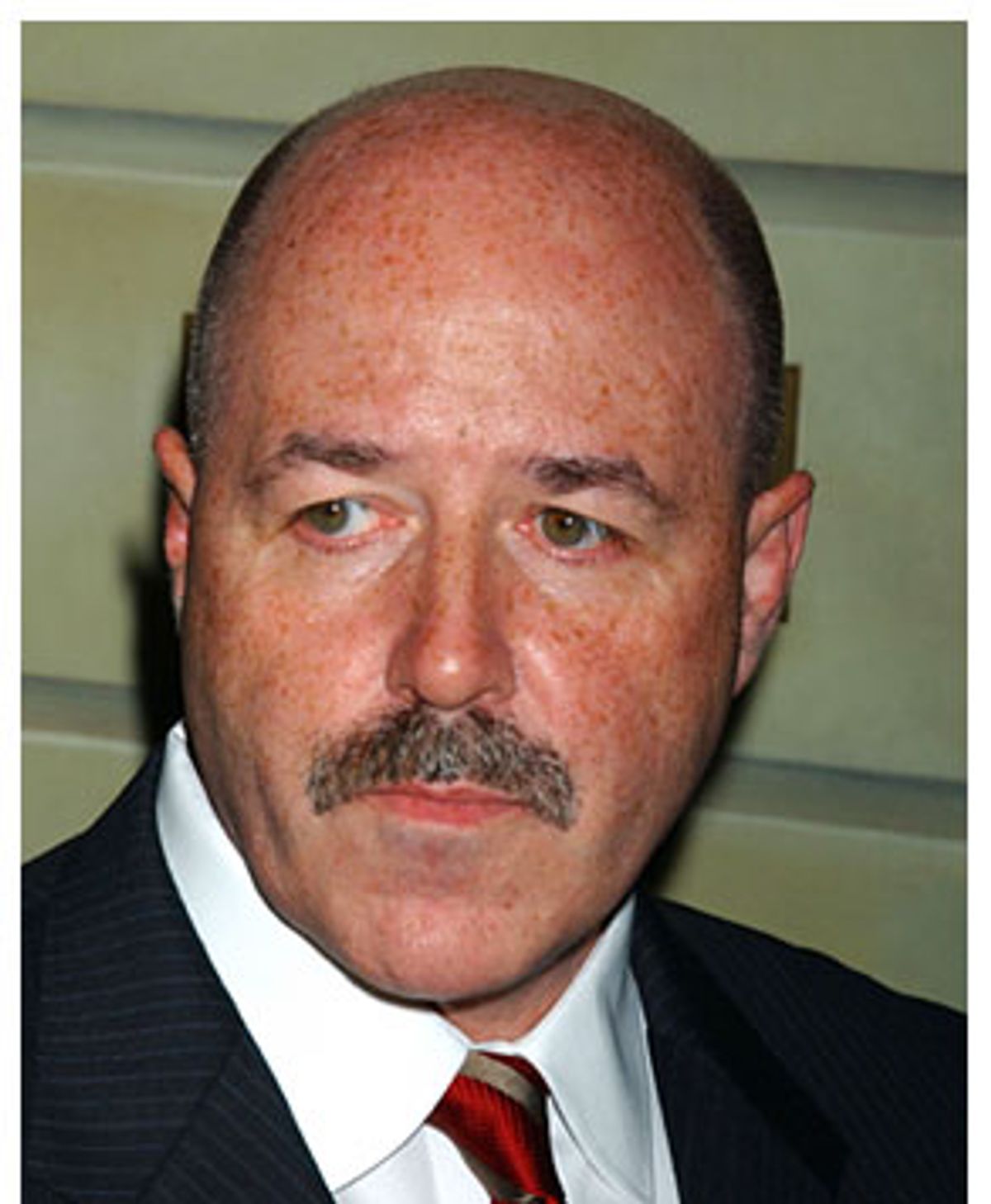

In the legend of the war on terrorism, Bernard Kerik, with his trademark shaved head, bristling mustache and black belt in karate, occupies a special place as rough-and-ready hero. Having risen from military policeman to narcotics detective to New York police commissioner, he finds himself on the fateful Sept. 11, 2001, shoulder to shoulder with former Mayor Rudy Giuliani. As the towers crumble the mayor confides in his buddy, as Giuliani recalled in his speech to the Republican National Convention: "Bernie, thank God George Bush is president." After the invasion of Iraq, Bush assigns Kerik to train the new Iraqi security forces. Mission accomplished, he returns to Giuliani Partners LLC and becomes motivational speaker to captains of industry, his net worth skyrocketing into the millions of dollars. One of his most notable aphorisms: "Political criticism is our enemies' best friend."

Kerik, the decorated detective, leads an investigation into the safety of cheaper Canadian prescription drugs and accompanies Giuliani to his appearance before the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations, where he testifies on their danger. (Kerik and Giuliani are rewarded handsomely by their client, the U.S. pharmaceutical drug lobby.) After John Kerry closes the gap in the presidential debates, Kerik rushes to the rescue, ominously warning of terrorist attacks: "If you put Senator Kerry in the White House, I think you are going to see that happen ... and I don't want to see another 9/11." At last, having pledged to keep America "safer," Bush announces Kerik, rags-to-riches personification of post-9/11 resolve, as the new secretary of homeland security. The legend lives on.

The Department of Homeland Security is a bureaucratic Byzantium consisting of 22 agencies with a budget exceeding $40 billion. Its current secretary, former Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Ridge, has made it best known for his announcement of color-coded terrorist alerts and his call to citizens to wrap their houses with plastic and duct tape. The department's notorious dysfunction prompted a devastating analysis by expert Stephen E. Flynn in this fall's Foreign Affairs: "The transportation, energy, information, financial, chemical, food, and logistical networks that underpin U.S. economic power and the American way of life offer the United States' enemies a rich menu of irresistible targets. And most of these remain virtually unprotected."

The department's creation was first proposed in the report of the bipartisan U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century, commissioned by President Clinton and delivered to President Bush. "A direct attack against American citizens on American soil is likely," it warned. Like the pre-9/11 alarms by the CIA and the National Security Council's former counterterrorism chief, Richard Clarke, this was studiously ignored by the Bush administration, which had dismissed terrorism as a "soft" issue, a "Clinton thing."

After 9/11, Senate Democrats proposed a new department, which Bush initially resisted. Then he offered his own version that would deny labor union recognition to workers. In the midterm elections of 2002, Bush declared that the Democrats were "not interested in the security of the American people." Republican TV commercials morphed the faces of Osama bin Laden, Saddam Hussein and Democratic senators into one another -- and the Republicans captured the Senate.

Kerik's appointment was suggested to Bush by Giuliani. With this favor, Kerik's meteoric career has reached its zenith. The son of a prostitute, high school dropout Kerik fathered an illegitimate daughter in Korea whom he refused to acknowledge and support. He was a bodyguard for members of the Saudi royal family and then became a New York narcotics cop. In 1993, he was tapped as Giuliani's chauffeur and bodyguard. It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Giuliani made Kerik deputy police commissioner and chief of the Corrections Department, a Republican patronage dump. One million dollars in taxpayer money used to buy tobacco for inmates disappeared into a private foundation run by Kerik without any accounting. In 2000, Giuliani leapfrogged Kerik over many more qualified candidates to appoint him police commissioner.

Kerik's coordination of command and control on 9/11 was excoriated as "not worthy of the Boy Scouts ... a scandal" by John Lehman, the conservative Republican member of the 9/11 commission.

After 9/11 Kerik spent much of his time writing a self-promoting autobiography, "The Lost Son." The city's Conflict of Interest Board eventually fined him $2,500 for using three policemen to conduct his research. Kerik developed a close relationship with his publisher, Judith Regan, of Rupert Murdoch's HarperCollins. When she told him her cellphone was missing after a TV appearance on Fox News, Kerik sent detectives in the middle of the night to question the TV employees. It turned out Regan had simply misplaced the phone. Kerik made her an honorary police commissioner.

Dispatched to Iraq to whip Iraqi security forces into shape, Kerik dubbed himself the "interim interior minister of Iraq." British police advisors called him the "Baghdad terminator," and reported that his reckless bullying was alienating Iraqis. "I will be there at least six months -- until the job is done," he said. He left after three.

In waging bureaucratic battles among complex organizations and players, Kerik has less experience in Washington than he had in Baghdad. He cannot be expected to change the funding formula determined by Bush's political calculations to favor interior Republican states -- more per capita to Montana than to New York. And, undoubtedly, many of those seeking the department's lucrative contracts will be signing up as clients of Giuliani Partners. The looting of Washington, unlike post-invasion Iraq, is legal.

In line with other second-term Cabinet appointments -- Alberto Gonzales as attorney general, Condoleezza Rice as secretary of state -- Kerik will be an enforcer, a loyalist and an incompetent. In the made-for-TV version of the Bush administration he plays Kojak; in the true-life version he would be played by Peter Sellers. He is a deadpan caricature of a parody. Now the body man becomes the body. The resemblance is less to Inspector Clouseau or Chauncey Gardiner than to Caligula's horse.

Shares