Recent history offers many examples of Americans' inability to tell fact from fiction, but none more tangled than the story of Dan Brown's "Da Vinci Code." The book is among the most popular novels of all time, with 8 million copies sold since its publication last year and what seems to be a permanent reserved slot on the bestseller list. You see people reading it on planes and trains, and if at a social event you happen to mention that you write about books for a living, someone is sure to pull you aside eagerly to discuss it. This baffles and annoys a lot of literary types, many of whom haven't read "The Da Vinci Code" or couldn't get past the first few hackneyed pages. Why is the public so preoccupied with this cheesy thriller? they wonder.

"The Da Vinci Code" is indeed a cheesy thriller, with all the familiar qualities of the genre at its worst: characters so thin they're practically transparent, ludicrous dialogue, and prose that's 100 percent cliché. Even by conventional thriller standards, the book isn't particularly good; the plot is simply one long chase sequence, and the "good guy who turns out to be evil" is obviously a ringer from the moment he's introduced. Dan Brown is no Robert Ludlum, so why has his thriller so outdistanced the work of his betters?

The answer is that what readers love about the novel has nothing to do with story, or character, or mood, or any of the qualities we admire in good fiction. They love it because of the nonfiction material the book supposedly contains, a complicated, centuries-spanning conspiracy theory. The people who buttonhole me at parties and barbecues to talk about "The Da Vinci Code" usually can't even remember the names of the novel's two main characters or anything that happens to them. What entrances these readers is the possibility that a secret society has protected a religious and historical secret for almost 2,000 years, a secret that could undermine Christianity as we know it. "It really makes you think," an earnest arts administrator told me last summer.

The story begins with the murder of a curator at the Louvre and follows his estranged granddaughter, a French cryptologist, as she and a handsome Harvard professor attempt to solve the crime while evading the police (who suspect them in the murder) and assorted bad guys. Little by little, various characters reveal to the cryptologist that her grandfather headed up a shadowy group called the Priory of Sion, whose past leaders included such luminaries as Isaac Newton and, of course, Leonardo da Vinci.

With the Knights Templar (an order of medieval crusaders), the Priory has guarded proof of the marriage of Jesus to Mary Magdalene. Furthermore, they have proof of the child produced by that marriage, who is said to have founded a dynasty of French kings. Clues to this secret can supposedly be found, among other places, in Leonardo's paintings (particularly "The Last Supper") and in early Christian scripture suppressed by the church. The legend of the Holy Grail really refers to Mary Magdalene (vessel of Jesus' blood), who also stands for the "sacred feminine," a principle Brown claims was purged from the faith by church fathers.

Fortunately for Brown, as the book has filtered into the awareness of people who are qualified to refute most of its claims, he's always been able to plead fiction; "The Da Vinci Code" is, after all, only a novel. Although he begins the book with a statement that it accurately describes real documents, and that the Priory of Sion really does exist, even this leaves him with plenty of wiggle room. The book's selling point is the impression that it contains large and provocative servings of historical fact; yet when challenged on the many fallacies in his novel, Brown can always assert that, as a work of fiction, "The Da Vinci Code" can't be held to any standard of accuracy.

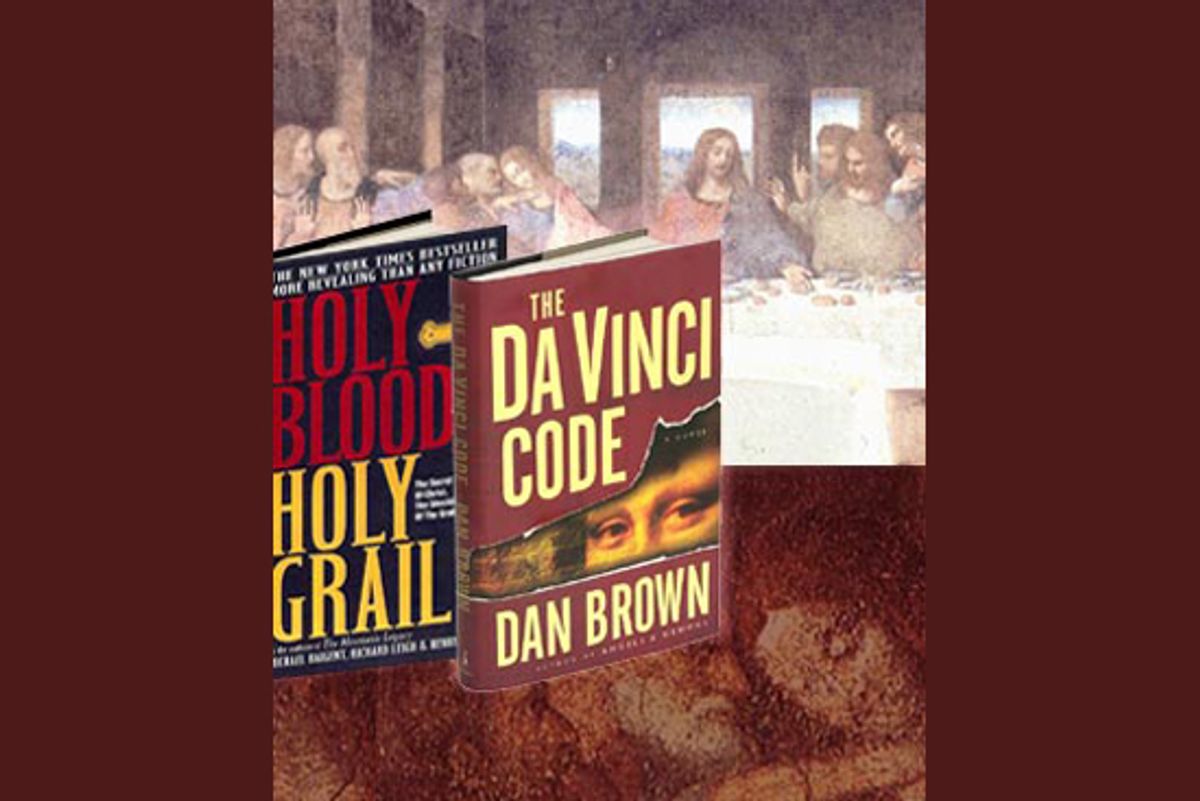

A cozy situation for Brown, but it became somewhat less so recently when, in the U.K., a lawsuit was filed against him for "breach of copyright of ideas and research." The complainants, Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh, are the coauthors, with Henry Lincoln, of "Holy Blood, Holy Grail," a bestseller from the early 1980s. Virtually all the bogus history in "The Da Vinci Code" -- nearly everything, in other words, that today's readers' find so electrifying in Brown's novel -- is lifted from "Holy Blood, Holy Grail."

This puts both Brown and the authors of "Holy Blood, Holy Grail," in a tricky position. Baigent et al. have always maintained that the "facts" supporting their theories are available to any dedicated scholar and that the theories themselves, while unconventional, have been seriously entertained by other "experts," (including some, they claim, in the "upper echelons" of the Roman Catholic Church).

Since "Holy Blood, Holy Grail" presents itself as nonfiction, it has been in its authors' interest to downplay how much of it is invented. However, if the "research" and ideas in "Holy Blood, Holy Grail" are not the original creations of the book's authors, they become harder to copyright, and the possible infringement suit against Brown might be weakened. No one, after all, has a copyright on the facts surrounding Abraham Lincoln's assassination or the Treaty of Versailles.

For Brown's part, it's to his advantage to insist that the farrago of lies and misrepresentations used to prop up the conspiracy theory in "The Da Vinci Code" (and, originally, in "Holy Blood, Holy Grail") is part of the historical record or at least in general circulation. Perhaps that's why Brown, who has avoided talking to the press about the accuracy of his book since "The Da Vinci Code" became a hit and drew fire from historians, granted a lengthy interview to the makers of "Unlocking da Vinci's Code: The Full Story." The documentary recently aired on the National Geographic Channel and earned the 5-year-old cable network its highest rating ever.

"That information has been out there for a long time," Brown told the filmmakers when asked about the historical "underpinnings" of his novel, "and there have been a lot of books about this theory. The interesting thing is that they're all history tomes that sit in the back corner of bookstores. 'The Da Vinci Code' has taken a lot of that information and put it in a different genre, and there's an enormous part of the population now that's hearing this for the first time. And it feels brand new."

But what exactly is this "information"? The theories encompassed in "Holy Blood, Holy Grail" and its derivative, "The Da Vinci Code," have a certain invincible panache. They are proof of the adage that the hardest lie to refute is the Big Lie. Unlike, say, speculation about the "real" author of Shakespeare's plays, these theories span so many historical specialties -- ancient Hebrew customs, early Christian texts, regional French folklore, ancient and contemporary church history, medieval dynastic minutiae, Renaissance and neoclassical art, esoteric movements of the early modern age, and so on -- that no one person has the expertise to refute all of the fabrications.

In fact, as enormous crocks of nonsense go, "Holy Blood, Holy Grail" is a kind of masterpiece, certainly more so than its pipsqueak descendant. In "The Da Vinci Code" Brown had one really good idea: to use a rudimentary thriller plot to spoon-feed readers the Grail theory concocted by Baigent, Leigh and Lincoln. You get the impression Brown never expected "The Da Vinci Code" to take the world by storm or that it would invite the kind of scrutiny his novel cannot withstand. As a result, Brown makes several dumb, careless mistakes that put the lie to his pretensions of extensive research, such as having a "Grail expert" describe the Dead Sea Scrolls as being "among the earliest Christian records," when the documents are Jewish and do not mention Jesus Christ at all.

The authors of "Holy Blood, Holy Grail," who girded their loins against attacks from legitimate historians from the very start, knew better than this (although they do erroneously refer to the collection of largely Gnostic texts found in Nag Hammadi, Egypt, as "scrolls" rather than books, and they include the Gospel of Mary among the texts in that collection, though it was found elsewhere). When it comes to spinning a masterful line of bull, they have few equals, and if we cannot admire them, we can at least respect their peculiar genius, much as Sherlock Holmes respected the Napoleon of crime, Professor Moriarty.

Baigent, Leigh and Lincoln are the Moriartys of pseudohistory, and "Holy Blood, Holy Grail" is their great triumph. Their techniques include burying their readers in chin-high drifts of factoids -- some valid but irrelevant, some uncheckable (the untranslated diaries of obscure 17th century clerics, and so on), others, like the labyrinthine family trees of various medieval French noblemen, simply numbing, and if you trouble to figure them out, pretty inconclusive. A preposterous idea will first be floated as a guess (it is "not inconceivable" that the Knights Templar found documentation of Jesus and Mary Magdalene's marriage in Jerusalem), then later presented as a tentative hypothesis, then still later treated as a fact that must be accounted for (the knights had to take those documents somewhere, so it must have been the south of France!).

Each detail requires extensive effort to track down and verify, but anyone who succeeds in proving it false comes across as a mere nitpicker -- and still has a blizzard of other pseudofacts to contend with. The miasma of bogus authenticity that the authors of "Holy Blood, Holy Grail" create becomes impenetrable; you might as well use a rifle to fight off a thick fog.

Nevertheless, the Grail theory touted in "Holy Blood, Holy Grail" and "The Da Vinci Code" can be broken down into two main parts: One concerns the historical details of Jesus' life and the establishment of orthodox Christian tenets in the three centuries after his death. The second part describes the survival of the suppressed, hidden and unorthodox "truth" about Jesus and his descendants via the Priory of Sion and its military arm, the Knights Templar. Clues to this truth are supposedly embedded in the art, architecture and literature produced by the intellectual superstars who, with the occasional aristocrat, are said to have run the Priory of Sion. (Why people who are sworn to keep this secret would go around planting all these clues is never explained.)

Almost all the furor "The Da Vinci Code" has caused in America surrounds the first part of this theory. In the past year, numerous books have been published refuting the novel's depiction of Jesus' life and Christianity's early years, but most of these have been written by defensive evangelicals. They aren't particularly interesting to a secular reader -- or reliable, since their authors are deeply invested in a particular view of Jesus. They don't apply standards of proof (or, to be precise, plausibility) of much use to nonbelievers.

Fortunately, Bart D. Ehrman, who chairs the department of religious studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has just published "Truth and Fiction in the Da Vinci Code" (Oxford University Press), a book-length expansion of his list of 10 errors in Brown's novel, first circulated widely on the Internet. Ehrman's specialty is the ancient history of the Christian church, and he is the author of two books, "Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew," and "Lost Scriptures: Books That Did Not Make It Into the New Testament" (both Oxford University Press), so he can hardly be accused of participating in a coverup of the unorthodox and heretical early Christian texts that the authors of "Holy Blood, Holy Grail" and Brown claim support their theories.

"Truth and Fiction in the Da Vinci Code" is written in eminently clear, basic English (a pleasant surprise, because Ehrman's previous books can be pretty heavy sledding), and its tolerant, "more in sorrow than in anger" tone is probably more effective than the annoyance to which most of the novel's critics (including this one) succumb. It's a little repetitive, but given the many relatively unsophisticated readers Ehrman is addressing, that's probably justified.

Ehrman methodically demolishes a sizable chunk of the conspiratorial claims in "The Da Vinci Code," which are mostly cribbed from "Holy Blood, Holy Grail." To hit some of the high spots: Early Christian texts excluded from the New Testament did not depict Jesus as human rather than divine; in fact, quite the opposite. The emperor Constantine was not involved in establishing the New Testament's canonical texts; it was a process that began before his reign and continued after his death. Jesus' experiences and teachings were not recorded by "thousands" of his followers during his lifetime, as nearly all of them were almost certainly illiterate. It was not unheard-of for a Jewish man of Jesus' time to be either single or celibate, particularly if he was part of the apocalyptic prophetic movement of the day, as Jesus most likely was.

Some of Brown's mistakes are minor but telling. For example, his "Grail expert," Leigh Teabing, smugly declares that "any Aramaic scholar will tell you" that the word "companion" used in the uncanonical Gospel of Philip in describing Mary Magdalene's relationship to Jesus, "in those days, literally meant spouse." But, as Ehrman explains, the Gospel of Philip is written in Coptic, not Aramaic, and the word in question is borrowed from yet another language, which is also not Aramaic, but Greek. And it does not mean "spouse" or "lover," but "companion," and is "commonly used of friends and associates."

Brown picked up this bit of bogus "proof" from "Holy Blood, Holy Grail." (In a lumbering stab at playfulness, Leigh Teabing is named after the coauthors, "Teabing" being an anagram of "Baigent.") The authors of "Holy Blood, Holy Grail" in turn got it from the Protestant theologian, William E. Phipps, who, in an admirable effort to liberalize church attitudes toward women and sex, made the claim in "Was Jesus Married?" a "theological potboiler" published in the early '70s. The mistranslation of the Gospel of Philip has been kicked around for a while (it turns up in the National Geographic documentary, for example), but not, seemingly, by anyone who can read the languages in question.

Ehrman does not concern himself with the modern component of the Grail conspiracy theory. In fact, the Priory of Sion element of the theory has received little attention in America, which is surprising when you consider that this organization is supposedly still extant, possesses proof positive of Jesus' bloodline, and could settle the matter once and for all. The fundamentalist vein in American culture makes a fetish out of scriptural legitimacy and, as a result, quarrels over the exact nature of Jesus and his ministry attract all the heat.

But the latter-day aspects of this conspiracy theory are important. After all, both "The Da Vinci Code" and "Holy Blood, Holy Grail" begin with a contemporary puzzle that leads investigators down a long, twisted path to the biblical past and the "truth" about Jesus and Mary Magdalene. In Brown's novel, the murder of a Priory of Sion master draws his granddaughter and the hero, Robert Langdon (a professor of "symbology" -- a nonexistent discipline -- at Harvard), into the story. In "Holy Blood, Holy Grail," the question of how a priest in a provincial French town suddenly acquired a lot of cash and posh social connections sets the authors on the trail.

So, in both the novel and the "nonfiction" work, there is a mystery that, when pursued, leads to evidence of a secret society dedicated to protecting yet another secret. Unless the secret society actually does exist, the persuasive litany of "clues" ostensibly alluding to its existence and the nature of its closely guarded secret is meaningless. If Leonard da Vinci had not been privy to the secret that Mary Magdalene stood foremost among Jesus' disciples and bore his child, he would not have planted "codes" in his paintings intimating as much. And then there would be no reason to read great significance into the fact that the figure Leonardo painted to right of Jesus in "The Last Supper" is pretty and beardless with long flowing hair and that this figure's left arm, with Jesus' right arm, forms a V shape, symbol of "the sacred feminine"!

If you point out to a "Da Vinci Code" buff that there's plenty of artistic precedent for depicting the disciple John as young and beardless, he will talk about the Gnostic gospels that supposedly hint at intimate relations between Jesus and Mary Magdalene. And if you point out that other suppressed scripture suggests exactly the opposite, he can point to the weird and ominous carvings in a church in a tiny town in southern France, which surely support the idea that a terrible secret was buried there. This is how conspiracy theory works: Build a big enough pile of suggestions and to some people it will look like truth. "Evidence" of a secret society in turn becomes "evidence" of a secret that the society protects; each phony scenario props up the next.

The Priory of Sion did exist -- sort of -- but not in any form even remotely resembling the fantastical claims of the authors of "Holy Blood, Holy Grail" or Brown. (In one of his few unqualified claims to nonfiction, Brown includes the sentence "The Priory of Sion -- a European secret society founded in 1099 -- is a real organization" on a page labeled "Fact" placed before the prologue of "The Da Vinci Code.") In reality, the Priory of Sion was the invention, in the 1950s, of a man named Pierre Plantard who had a history of fraud, embezzlement and membership in ultra-conservative, quasi-mystical and virulently anti-Semitic Catholic groups. These tiny extremist groups sought the reunification of Europe under the dual leadership of an orthodox Roman Catholic Church and a divinely ordained monarch, somewhat like the Holy Roman Emperor and preferably French.

Plantard learned of rumors surrounding a town in southern France, where the late priest's unexplained affluence led to talk of buried treasure in the local church. (The priest's wealth actually came from charging superstitious Catholics to have Mass said on their behalf, and he was censured for it by the church.) Plantard capitalized on the "mystery" of Rennes-le-Château by insinuating into the grapevine further rumors: that the priest had discovered evidence of an explosive secret and was being bribed to keep it under wraps.

Plantard wanted to pass himself off as the descendant of the Merovingian dynasty, a family of medieval French kings and, ultimately, of Jesus and Mary Magdalene. (In reality, he was the son of a butler and a cook.) With his accomplice, a genuine but dissolute aristocrat and expert forger, Phillipe de Chérisey, he produced a set of fabricated parchments full of encoded and suggestively prophetic verse alluding to this Merovingian fantasy. With a restaurateur interested in drumming up tourist business for his establishment (located in the priest's former villa), they disseminated a story that the priest had discovered these parchments in the church, inside a hollowed-out pillar of Visigoth origins. (The pillar was later determined to be solid.)

The parchments and a variety of other faked documents pertaining to the Priory of Sion and the Merovingians -- including that list of past Grand Masters, featuring Leonardo and Newton -- were planted in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. This institution, alas, cannot be said to run a tight ship, and there are apparently no records indicating who exactly deposited the infamous "dossiers secrets" in their collection. However, investigators eventually determined that the printing press used to produce them was the same press used by Plantard to print his right-wing newsletters and broadsides.

The entire case for the existence of the Priory of Sion and the bloodline of Jesus extending into the French monarchy rests on this cache of bogus documents. There is no other "proof" anywhere that the Priory of Sion ever existed. A third confederate of Plantard and de Chérisey's, Gérard de Sède, who seems to have bought the story initially, published a lurid bestseller about the "mystery" of Rennes-le-Château. At this point, once a truly interesting sum of money entered the picture following the book's success, the three men fell out, quarreling over who deserved how much of the proceeds.

They began to tell outsiders of the scheme and eventually, de Chérisey confessed on camera, displaying the forged parchments and explaining the methods used to produce them to the French journalist Jean-Luc Chaumeil, who has devoted himself to exposing the hoax. Plantard tried intermittently to sustain the fable, but in the 1980s, he got into trouble with French authorities when a financier who Plantard had claimed was a member of the Priory of Sion committed suicide. In the subsequent police investigation, Plantard was forced to admit he'd invented the whole thing.

Although the Priory of Sion hoax had been debunked within France, the authors of "Holy Blood, Holy Grail" were still able to pass it off as authentic in their book and in subsequent media appearances. (Insiders swear the authors knew all along that the story was phony.) Even today, with "The Da Vinci Code" and its preposterous conspiracy theories on the lips of 8 million American readers (and more worldwide, now that translations are appearing), the truth about the Priory of Sion -- a major component of the novel -- isn't widely known. (An excellent summary of the case by Amy Bernstein, based on French sources, can be found in "Secrets of the Code," a collection of writings of varying degrees of gullibility, edited by Dan Burstein. Exhaustive documentation of the multifarious frauds of Pierre Plantard can be found at the Web site maintained by Paul Smith.)

Without the Priory of Sion to hold the Grail conspiracy theory together, most of the provocative "evidence" Brown presents in "The Da Vinci Code" crumbles. Take that supposedly ambiguous figure to the right of Jesus in Leonardo's "Last Supper." If there's no real reason to suspect Leonardo of believing in a special relationship between Mary Magdalene and Jesus Christ, why should we see that figure as a woman? Yes, the figure looks somewhat feminine but, in addition to following established conventions in representing the disciple John, Leonardo was quite fond of painting androgynous-looking young men. His reason for doing this was the same one that Michelangelo had for painting lots of muscular male nudes and Botticelli had for depicting long-limbed, ivory-skinned lovelies. You don't need a degree in symbology to figure that one out.

This emphasis on Leonardo is one of the few original additions Brown has made to the Grail conspiracy theory. (Plantard and the authors of "Holy Blood, Holy Grail" focused on Nicolas Poussin, an important French painter who is relatively little known to Americans, but whose "Bergers d'Arcadie" is a node of significant kook fascination elsewhere.) Brown's other contribution is the introduction of the idea that the Priory of Sion is a champion of "the sacred feminine," a foggy spiritual principle with roots in "paganism," supposedly purged from early Christianity by the dastardly Constantine.

Although this notion is so vaguely conceived that it approaches stupidity -- What "pagans"? People who have worshipped multiple gods range from the ancient Greeks to Hindus to the Norse and the Aztecs, and their religions have little in common and are certainly not free from patriarchal values -- the intention is hard to argue with. A significant portion of the fan base for "The Da Vinci Code" consists of women who are uncomfortable with the male-dominated, slightly to very misogynistic nature of the Christianities they were raised in and who see Brown's version of early Christian history as a corrective.

As Ehrman points out, it does appear that women had a more prominent role in Jesus' ministry than might be expected of a religious movement at that time and place. Some of that status is apparent in the canonical texts. The New Testament, most notably, holds that women, particularly Mary Magdalene, were the first witnesses to the Resurrection. Yet Ehrman also concludes that while some of the early Christian texts excluded from the New Testament honor Mary Magdalene and Jesus' women followers, others emphatically do not.

The early Christian scriptures -- the earliest having been transcribed from oral accounts 30 years after Jesus' death, and some a century or more later -- were written by people who were the product of a patriarchal culture that subscribed to many values we abhor today -- slavery, for one. Most of Jesus' followers assumed the world as they knew it was about to end very soon, to be replaced by an earthly kingdom of heaven. They were wrong about that and a lot of other things. To try to recast them as people with egalitarian attitudes about the sexes is to imply that we can't improve our own society without some kind of precedent from them. This idea could be even sillier than anything in "The Da Vinci Code."

Shares