Tough-but-tender blondes who harbor deadly secrets; upstanding citizens with reputations to protect; kids from the other side of the tracks whose common decency always shines through: There are a million stories in the naked city, but there are a million more in high school. "Veronica Mars" has dug up some of the best ones.

In its first season "Veronica Mars," which its creator, Rob Thomas, originally envisioned as a series of noir novels for young adults, neither sentimentalized the high-school experience nor milked it for Janis Ian-style pathos. Instead, Thomas and his writers took the seemingly mundane matters that seem like life-or-death issues to a teenager (What does it say about me if I'm invited to eat at the rich kids' table? How do I feel about my old boyfriend going out with another girl?) and turned them into something more than just metaphors.

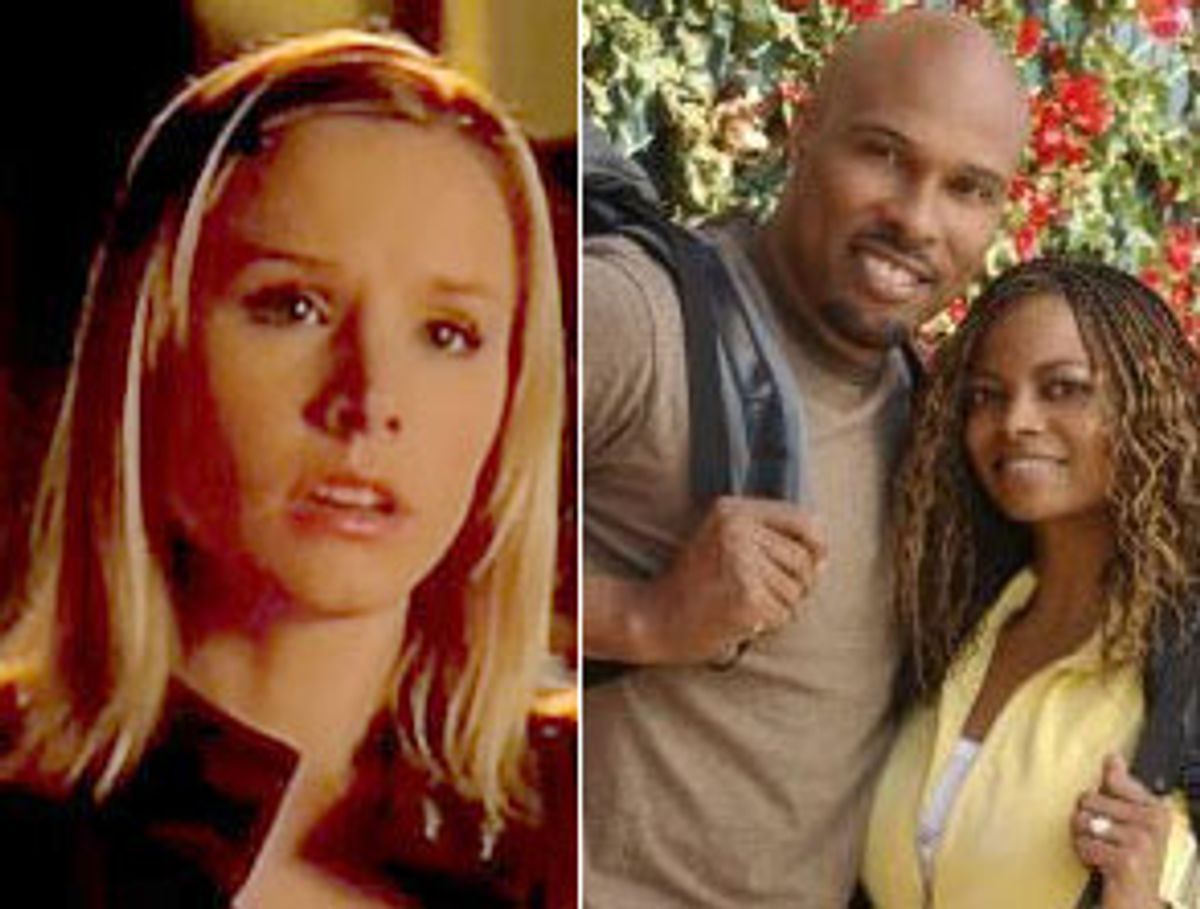

The show's heroine, Veronica Mars (Kristen Bell), who helps out part-time with the private-investigation business run by her dad, Keith Mars (the wonderful Enrico Colantoni), is so well-adjusted and self-possessed (and so sharp with a one-liner) that she barely fits in with the adults around her, let alone the kids. Formerly part of the "in" crowd in the Richie-Rich town of Neptune, Calif., she and her dad are now financial and social outcasts. (He used to be the town sheriff, but lost his job when he refused to go along with the easy and, of course, incorrect assumption regarding the perpetrator of the town's most scandalous murder.) Veronica is the perfect gumshoe loner, like a much prettier Bogey in jeans and a hoodie, and on last night's season finale, she finally unlocked the secret to the mystery that has tortured her for the better part of the school year: She caught the murderer of her best friend, Lilly Kane (Amanda Seyfried), who, the year before, had been found near the family pool with her head bashed in. (The murder weapon, we learn, was a red crystal ash tray, costly, weighty and deadly.)

The season finale of "Veronica Mars" -- the show has, thankfully, been renewed for another season -- was just the sort of satisfying capper you look for in a series that, week after week, keeps you asking questions. We found out whodunit (Aaron Echols, played by Harry Hamlin, the movie-star father of Logan Echols, Lilly's boyfriend) and why (he was sleeping with Lilly, and there were incriminating videotapes). But in keeping with the show's sharp, inquisitive sensibility, in addition to answering all our questions this season finale opened up some new ones: Veronica's mother (Corinne Bohrer), who left the family suddenly and mysteriously only to return after a stint in a rehab joint for alcoholics, apparently hasn't kicked her habit -- and while we all like to think, wistfully, that it's always better for families to remain intact, "Veronica Mars" has the guts to explore the idea that some families are better off splintered. We don't know what has happened to Logan (Jason Dohring), whom Veronica at one point suspected of having murdered Lilly; he was last seen teetering, drunk and depressed, on the edge of a bridge. (The additional complication is that he has fallen hard for Veronica, a turn of events that has given him some complicated, fascinating angles, as well as upped his charm.) And in the episode's final scene, Veronica, having dropped into bed, exhausted (she's just saved her father's life), is awakened by a knock at the door. She opens it, and we can't see who's standing on the doorstep, but Veronica's face glows with a relieved, relaxed radiance we haven't seen in her for several episodes.

"I was hoping it would be you," she says, with just a hint of flirtation. And just at that moment, the image of her standing in the doorway fades away from us, a gentle, soothing cliffhanger to keep us suspended until next season.

It's fitting that the first season of "Veronica Mars" ends with more questions than answers. The answer to "Who killed Lilly Kane?" has turned out to be relatively clear-cut. But the whodunit structure of "Veronica Mars" is something of a red herring, because what really entangles us, and keeps us on the hook, are the bigger questions -- they're the key to the show's momentum, its sly sense of fun, and its emotional resonance. Veronica is played by Bell with such eminently reasonable self-assurance that we're almost fooled into thinking we don't need to worry about her -- with her small frame, no-nonsense blond locks and dark, glittering eyes, she seems both sophisticated and mischievously elfin. Veronica can, and does, take care of everything: She tries hard to help out with the family finances, and she gives up her own hard-earned college savings to help her mother straighten out so she can come home. Each successive episode only confirms Veronica's perceived invincibility -- which is why it's so devastating when we see her confused or afraid, or when she's overcome with missing her mother. And in some ways, I think the show's most shattering revelation occurred in last week's episode: Before Lilly's death, Veronica attended a party with her upscale friends, only to wake up in a strange bedroom the next morning, unable to remember what had happened to her. Her panties had been removed, and she knew she had been drugged and raped -- but she didn't know who was involved, or how many people were involved.

The sexual assault was never a key plot point in "Veronica Mars" -- it was more of a heavy specter hanging over the show from week to week, rarely mentioned but always present. And while Veronica was humiliated and hurt by the experience, she never allowed it to define her or to drag her down. But naturally, she did want to know what happened to her. She asks questions of her classmates and friends, and entertains numerous what-ifs before finding the answer: It turns out that her then-boyfriend, Duncan Kane (Teddy Dunn), Lilly's brother, who had also been drugged at the party, had discovered her zonked-out in a guest bedroom and, in his own impaired state, decided it would be romantic to make love to her. The revelation is significant because it deals, in a shatteringly adult way, with the gray areas of human sexuality.

Did Veronica have sexual intercourse without her knowledge, and thus against her will? Yes. But was it her boyfriend's intent to rape her? No. It's made clear that, in Veronica's out-of-it state, she was happy to see Duncan, and she sent out signals that he understandably misread. The revelation doesn't allow Veronica the comfort zone of claiming easy victimhood, of railing against an unknown aggressor who intended to do her harm, because in some ways, Duncan was a victim too. The incident was tragic for both of them, an unpleasant (and potentially controversial) reality that the show wasn't afraid to crack wide open.

At the beginning of the season, in particular, "Veronica Mars" seemed like just the salve for all those still-in-mourning "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" fans out there (myself included). The two shows are similar in some ways. They both feature teenage girls -- blond California girls, to be exact -- with heavy-duty responsibilities: One has to solve a crime that has affected her deeply; the other merely has to save the world. But perhaps because of those broad similarities, it's become fashionable in some circles to trash "Buffy" in order to praise "Veronica Mars," as if all shows with teenage girls as heroines were required to be judged along some mysterious sliding scale of how "realistic" or "unrealistic" they are.

"Buffy" was a very different show from "Veronica Mars," with a markedly more fatalistic tone and an almost operatic sense of tragedy. But it did lay some crucial groundwork for "Veronica Mars": While both shows pretend to be geared toward a teen audience, it's really adults, well past the trauma of teenagerhood but still all too aware of how much it can sting, that gravitate toward them. The character Veronica is very much grounded in the real world: Formerly a member of the rich, cool crowd, she's now a pariah at her school; she has good reason to believe she's the victim of a rape, but she can't remember it; and, worst of all, her best friend has been murdered. To people with only a passing knowledge of "Buffy," the vampire slayer was a perky-but-serious teenager who spent nights trolling her town for the undead instead of studying for exams. But "Buffy" ultimately wasn't so much about the supernatural as it was about all-too-earthly confusion, suffering and fears. Recall how Buffy (Sarah Michelle Gellar) woke up on the morning after her 17th birthday, after having slept with her boyfriend, the "good" vampire Angel (David Boreanaz), for the first time, only to discover that he's not the man she thought he was -- in fact, he's no longer the man he thought he was. He has turned against her; he's unspeakably cruel to her. (It's not completely his fault -- he's been cursed.) But that turn of events was one of the most wrenching I'd ever seen on television, a supernatural version of a very realistic teenage fear: If I have sex with my boyfriend, will he, as the Shirelles once asked, still love me tomorrow? In Buffy's case, the answer was a horrifying no.

The heartbreak Buffy endured in Angel's bed is neither more nor less realistic than anything we've seen on "Veronica Mars." I think the fairest and most accurate way to compare the two is to accept that "Veronica Mars" is a continuation of a broad theme that "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" set in motion -- the idea that teenagers, as both Shakespeare and the Shangri-Las realized, are near-adults whose seemingly innocent disappointments and fears aren't really innocent at all: They're just nascent versions of our ongoing grown-up ones. I'm glad Veronica Mars solved the mystery of Lilly Kane's murder in this season closer, but what meant more to me was the way Veronica crumpled into her father's arms when he told her that he now knew for sure that he was really her father. (Some previous infidelities on the part of Mrs. Mars had made his paternity questionable.) The moment, played by two superb actors with ardent emotion and, amazingly, zero sentimentality, is a small instance of television perfection. Veronica and her dad are in charge of saving no world but their own, and that's enough.

Shares