On the second day of Kansas' mock trial of evolution, Kathy Martin created a moment to remember.

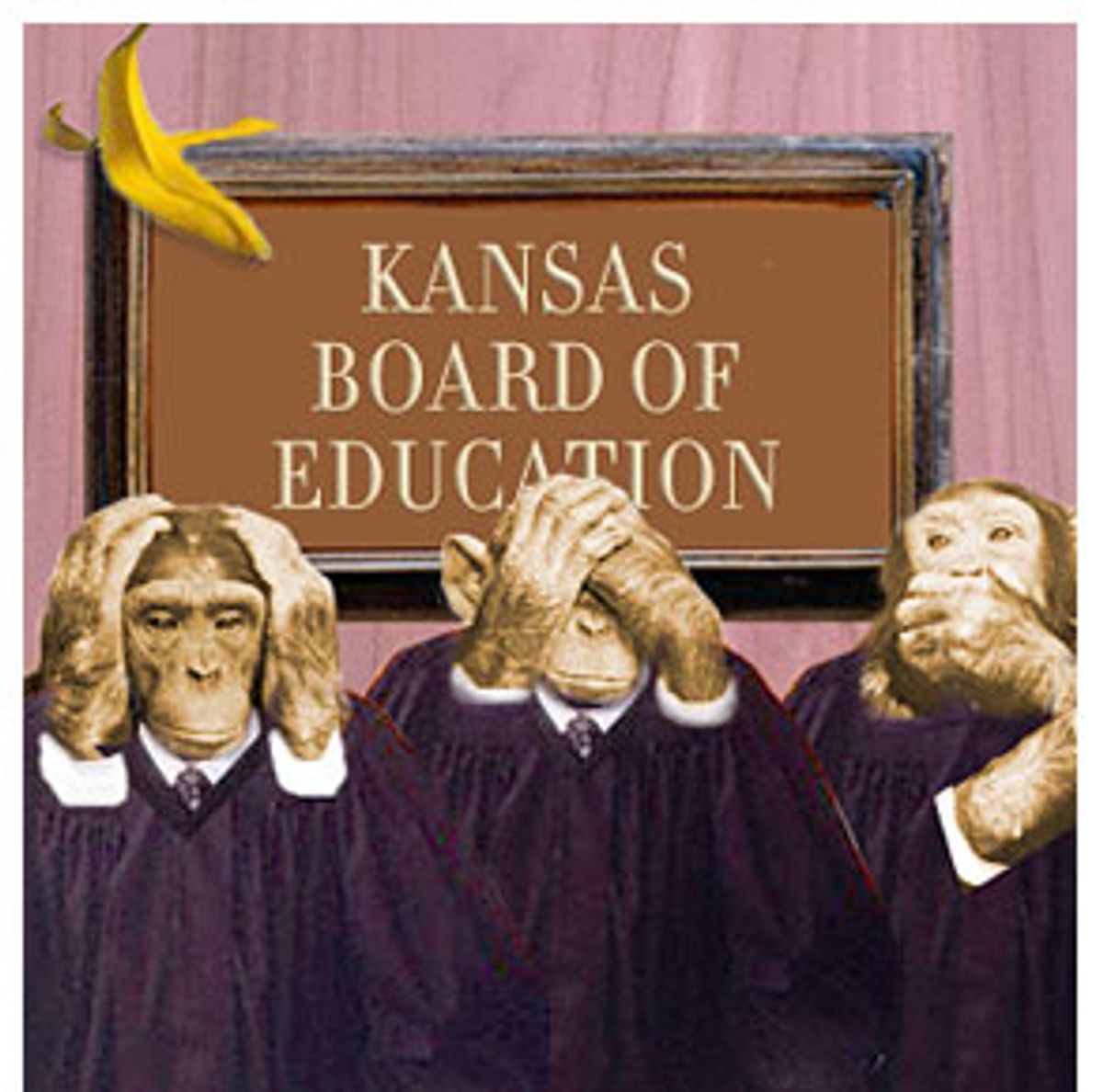

Martin is a member of Kansas' Board of Education and part of a 6-4 majority that appears dead set on changing state standards so the creationist theory of intelligent design, and perhaps other religious ideas, can be taught in science classes along with evolution. Martin and her creationist colleagues are ready to override a report recently issued by scientists and educators on Kansas' curriculum committee, which wants to keep the state's solid science standards intact.

But Martin had trouble even articulating just what she dislikes about the current standards. Martin, you see, has not really read the curriculum committee's report, nor does she think such scrutiny is necessary.

"Please don't feel bad that you haven't read the whole thing," Martin told a creationist "witness" at the hearings on the science curriculum, "because I haven't read it myself." Audience members groaned. To clarify, Martin later explained: "I'm not a word-for-word reader in this kind of technical information." So it went at Kansas' evolution hearings, which concluded Thursday, a Board of Education event where a concrete understanding of all that pesky technical information involved in science was apparently considered unnecessary to reach a verdict on evolution.

"This is absolutely and thoroughly a kangaroo court," says Jack Krebs, a science teacher who co-founded Kansas Citizens for Science (KCFS), a pro-evolution group, to combat the state's notorious 1999 decision -- since reversed -- to drop evolution from its required science curriculum. "The board committee was not even capable of understanding science at the high school level. They had neither the desire nor the competence to be any kind of judge." Nonetheless, having staged its elaborate mock trial, complete with testimony and cross-examination, the board is expected to approve by August new guidelines that many feel will allow religious views to be a part of science education.

Fearing the fix was already in for creationism, scientists around the globe adhered to a KCFS-organized boycott of the event, regarding it as a publicity stunt concocted by officials. "It's frankly not a controversy," said Alan Leshner, chief executive officer of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, about the hearings. "In the scientific community, evolution is an accepted fact." Krebs, though, sat through the hearings, which began in Topeka on May 5, watching a parade of creationists testify about intelligent design, and working with evolution's lone advocate in the proceedings: Topeka civil rights lawyer Pedro Irigonegaray, who concluded matters with a presentation highlighting the religious underpinnings of intelligent design -- the contemporary version of the 19th century argument that life is too complex to have evolved incrementally from simple forms.

Krebs, like others around the country who have stood up for evolution in recent years, regards the current creationist fixation on intelligent design as a wedge, intended to open the door to the introduction of a wide range of creationist ideas in science classrooms. For that matter, he also views the entire struggle over evolution as merely a wedge in the religious right's efforts to tear down the constitutional wall between church and state. "This is all part of a bigger political struggle," says Krebs, matter-of-factly. And some creationists agree. "If you believe God created [a] baby, it makes it a whole lot harder to get rid of that baby," Terry Fox, pastor of the Southern Baptist Ministry in Wichita, told a Washington Post reporter this spring. "If you can cause enough doubt on evolution, liberalism will die."

Indeed, while the battle over evolution is not necessarily fought along strict party lines, it contains many of the familiar dynamics of contemporary American party politics. Evolution's advocates feel they have the facts on their side but admit they struggle with complacency within their constituency. The pro-evolution forces also acknowledge they must catch up to creationists in organization and strategy, in order to combat a well-funded, aggressive opposition with a penchant for slick sound bites, message discipline, and a current strategy of cloaking radical aims in innocuous-sounding rhetoric. More than any other event this year, the mock trial in Kansas -- timed for the 80th anniversary of Tennessee's famous 1925 Scopes trial, in an apparent signal to religious fellow travelers -- bring these issues into sharp relief and lay bare the strategies and tactics of the two sides in this struggle.

More than anything else, the nature of the struggle in Kansas demonstrates how much creationist tactics have changed since the state's 1999 anti-evolution episode. Now as then, the driving force behind the creationists is Steve Abrams, a veterinarian, former Kansas gubernatorial candidate, one-time chairman of the state Republican Party, and current chairman of the Board of Education. In 1999, however, Abrams and his allies backed a version of creationism heavily dependent on the biblical creation stories in the book of Genesis. By contrast, for this month's hearings, the Board of Education brought in a long string of advocates of intelligent design, who argued that standard evolutionary biology is based on incomplete evidence and that some sort of designer must have been at work to develop life.

Abrams himself still publicly admits he is a so-called young-Earth creationist -- one who believes Earth is as little as 5,000 years old, based on a reading of the Bible. Intelligent design advocates are more likely to acknowledge an age closer to the current scientific standard -- 4.5 billion years -- and, in their testimony at the hearings, held fast to the current creationist strategy of publicly de-emphasizing religion as the source of their beliefs.

During cross-examinations, Irigonegaray asked questions intended to bring out this connection, making intermittent headway. For instance, when Russell Carlson, an intelligent design advocate and biochemist from the University of Georgia, testified, Irigonegaray queried him about the integral role a deity plays in the theory. "In your view the intelligent designer is God, is it not?" asked Irigonegaray. "Well, yeah, I would agree with that," Carlson replied. It may not seem likely that a Christian who believes in intelligent design pictures a designer other than God, but most intelligent design advocates were more circumspect in their answers than Carlson.

Looming behind this kind of sparring, like backdrops on a stage set, lie political and legal events that show why creationists are taking a more indirect approach. Politically, in 1999, Kansas became the butt of jokes after bluntly dropping evolution from its science requirements. The ensuing backlash helped pro-evolution moderates regain power on the Board of Education. "At the time, I said democracy got us into this and it will get us out of it," says John Staver, a professor of science education at Kansas State University, who co-chaired the state's science curriculum committee after the 1999 debacle and helped reinstitute evolution in the classroom.

But in 2004, some conservative Republicans unseated their more moderate GOP counterparts in primary elections for the Board of Education, tipping the balance back to the creationists. "When the primary elections were tallied last summer, we knew we would have an ultra-conservative religious-right majority of 6 to 4," says Staver. Democracy, he adds wryly, has "now gotten us back into it." Abrams, Martin, and their creationist colleagues promptly used the state's regularly scheduled curriculum review to reopen the door for creationism -- by handpicking pro-creationist allies to serve on the state's curriculum committee and draft their own report (as a counterpart to the one Martin has merely skimmed).

A principal aim of the creationists is to scrub the definition of "science" from Kansas classrooms -- now described as "human activity of systematically seeking natural explanations" for phenomena -- and to replace it with a more general definition lacking the words "natural explanations." If that sounds like an innocuous change -- well, that's the aim. By removing the notion of "natural explanations" as part of science, the creationists aim to give religion a foothold in the classroom, in the name of scientific balance.

"They are just as creationist as ever," Eugenie Scott, president of the National Center for Science Education, an Oakland, Calif., pro-evolution clearinghouse, told me in an interview before the Kansas hearings began. "But they've learned not just to boot evolution out, since that gets them laughed at on 'Letterman.'" Fox, the Wichita pastor, acknowledged as much in March: "The strategy this time is not to go for the whole enchilada. We're trying to be a little more subtle."

This approach is not just a political or public-relations strategy, however, but a legal one. The legal backdrop to the 2005 Kansas evolution dispute is, plainly, the U.S. Supreme Court's 1987 decision banning creation science from the classroom -- a ruling that also fits into some familiar-feeling political contours. When then-Gov. Bill Clinton of Arkansas lost his reelection bid to Republican Frank White in 1980, White, riding a wave of conservative confidence after the election, wasted little time signing the so-called Balanced Treatment Act mandating that creationism join evolution in the classroom. Based on the model recommended by the dominant creationist think tank of the time, the Institute for Creation Research in Southern California, the act featured an approach to creationism based on biblical literalism.

The American Civil Liberties Union challenged the Arkansas law in court and won, with the presiding judge ruling that the law was inspired by the book of Genesis, had "no scientific merit," and had as its sole goal "the advancement of religion." This violated the First Amendment by bringing sectarian beliefs into the classroom. Soon after, a Louisiana judge struck down a similar measure in that state -- a ruling creationists appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court upheld the ruling, with Justice William Brennan's majority opinion saying the Louisiana law was meant to "provide persuasive advantage to a particular religious doctrine that rejects the factual basis of evolution."

These days, therefore, Genesis and biblical literalism are out as the public rationales for creationism. Intelligent design and its leading think tank, the Discovery Institute of Seattle, are in, as creationists search for an approach that appears broad enough to withstand legal scrutiny. In this vein, this year the Kansas Board of Education also brought in advocates with a variety of religious backgrounds -- like Mustafa Akyol, a Turkish newspaper columnist and Muslim who tried to make the case that teaching evolution in the United States generates "anti-Westernism" in other parts of the world. In so doing, they are trying to present a public face for creationism that cannot be defined as representing a particular religious sect.

"I think there's no doubt that in order to solve some problems that got defeated back in the 1980s, the I.D. movement has been designed to make things look more like science, and less like religion," says Krebs. And it might work. While both sides, predictably, have claimed to have scored points at the hearings, the Kansas' Board of Education will almost certainly get its way for now.

That only underlines some of the inherent problems that evolution's advocates face -- like usually being in a reactive position. In most states, after all, science's backers merely want to maintain the status quo, while creationists can create energy for themselves by trying to overturn the established order. "It's an asymmetric situation," notes Nicholas Matzke, a spokesperson for the NCSE. Foundations like the Discovery Institute, which produced creationist witnesses at the Kansas hearings, are better funded than their pro-evolution opponents and churn out sound bites by the score. "Teach the controversy," for instance, is a favorite slogan of creationists, who say their own dissent is evidence that a scientific controversy exists.

Similarly, in many states, creationist efforts to change curricula are based on the template of the "Santorum language," a nonbinding statement that GOP Sen. Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania attached to the 2001 No Child Left Behind education bill, which stipulates that where "evolution is taught, the curriculum should help students to understand why this subject generates so much continuing controversy." That claim, evolution's backers say, is a back-door way of introducing religion-based theories of creation to science classes.

There are some basic rules of engagement evolutionists have developed in recent years, though. One is that these tussles are, ultimately, local. "It's always got to be an on-location fight," says Krebs. Politically, these are battles for seats on school boards, at both the state and the district levels, and involve monitoring the regular reviews of state science curricula, which usually occur every four or five years. Thus, getting local pro-science figures involved is crucial. Statements of support from the AAAS might sound good in theory, but local scientists carry much more influence.

Take the situation in New Mexico, one of the most interesting successes evolution's backers have had in striking back against creationists. After the state Board of Education slipped pro-creationism language into the curriculum standards in 1996, physicist Marshall Berman of Sandia National Laboratories ran for a position on the school board himself. Helped in part by the endorsements of New Mexico's admittedly high percentage of prominent scientists, Berman won a seat in 1998 and within about a year had changed the school standards back.

Berman also says he cultivated a strategy an increasing number of science groups are now taking up -- reaching out to moderates and religious leaders who are willing to accept evolution. "I think the appropriate approach is to make it very clear that this is not a struggle between religion and atheism," Berman says. "After people realized I didn't have horns and was not a monster ... we returned modern biology and geology to the curriculum." Like Krebs, Berman also believes that "evolution is just a wedge -- the beginning of an attempt to do away with the separation of church and state in this country." Thus he thinks a crucial part of forming a solid pro-evolution coalition is recruiting religious leaders who still appreciate that separation.

This is where national organizations can, in fact, combine with local pro-science groups to reach out to religious groups. The AAAS, for its part, is publishing a new book for distribution in religious communities this summer, "The Evolution Dialogues," about the process of balancing both religious belief and acceptance of evolution. "We're trying to demonstrate that it's not necessary to abandon faith to believe in evolution," says Jim Miller, a program manager at the AAAS who has led many of the organization's religious outreach efforts and who is also an ordained Presbyterian minister.

That may not be the approach favored by, say, fans of evolutionary biologist (and noted atheist) Richard Dawkins. But as Miller points out, many religious moderates already believe in the idea of a transcendent intelligence behind the world; intelligent design appeals precisely to these groups of people, "most of whom don't have any scientific background at all," he notes.

Finally, in states like Kansas and Michigan, where creationist efforts have coincided with state policy programs to improve the economy by developing the life-sciences industries, pro-science advocates are beginning to express support for evolution in economic terms: A good educational system will help the kids of today get jobs tomorrow and help attract business to the area. Even as his side suffers a setback in Kansas -- and in part because of it -- Krebs thinks active support for protecting the teaching of evolution will grow.

"The mainstream religious community, the business world, the scientific community, they haven't always taken this as a serious threat, but they're starting to," says Krebs. "We're seeing a much greater level of concern than we had in 1999." After all, the notion that bad science education can lead to fewer jobs in the future is an argument almost everyone can follow -- even if they don't want to read a bunch of technical stuff about science.

Shares