After I finished "In Search of Lost Time," I called the real literary types that I happen to know -- the ones who make their livings by being famously well-read -- and I asked them if they had read the whole thing, too. Mostly this was to introduce the idea that I had read the whole thing -- but I thought it was a good idea to first show deference to their superior reading programs before happening to mention this accomplishment with which I had impressed myself. Mais non! as they say in France. Yet all of them knew someone who had read all seven volumes; that person was Richard Howard, who introduces the Modern Library edition of the novel. I wondered: Could he be the only one other than me and Alain de Botton, who wrote "How Proust Can Change Your Life"? If so, I am here to tell you, we are a lucky group, and it is time for you to begin, because reading all of Proust is not hard.

First, you buy all seven volumes in a uniform edition -- mine came in a six-book set -- and you arrange them in a row next to your bed, the bathtub or your favorite chair, wherever you are most comfortable reading. For a few days, let's say no longer than a week, you glance at them from time to time and pick them up and look at the covers. You can even flip the pages -- but don't read anything. You are familiarizing yourself with this new acquaintance. You are coming to recognize his appeal. You are letting him impose upon you, because for the next 70 days or so, you are going to organize your free time around him.

You are going to find that he is both more friendly and more alien than you ever imagined. You are going to be charmed and also offended, sometimes disapproving, and occasionally bored. Quite often you are going to be impressed -- his capacity for thinking things through is going to seem almost infinitely great. Mostly, though, if you are like I was, you are going to come to anticipate your daily what? -- Dose? Encounter? Immersion? Meditation? -- with greater and greater eagerness but also greater and greater languor. You are going to come, at least in your own way, to feel French. When you have finished "In Search of Lost Time," you will be convinced that you know something visceral about Frenchness, and that that knowledge is important.

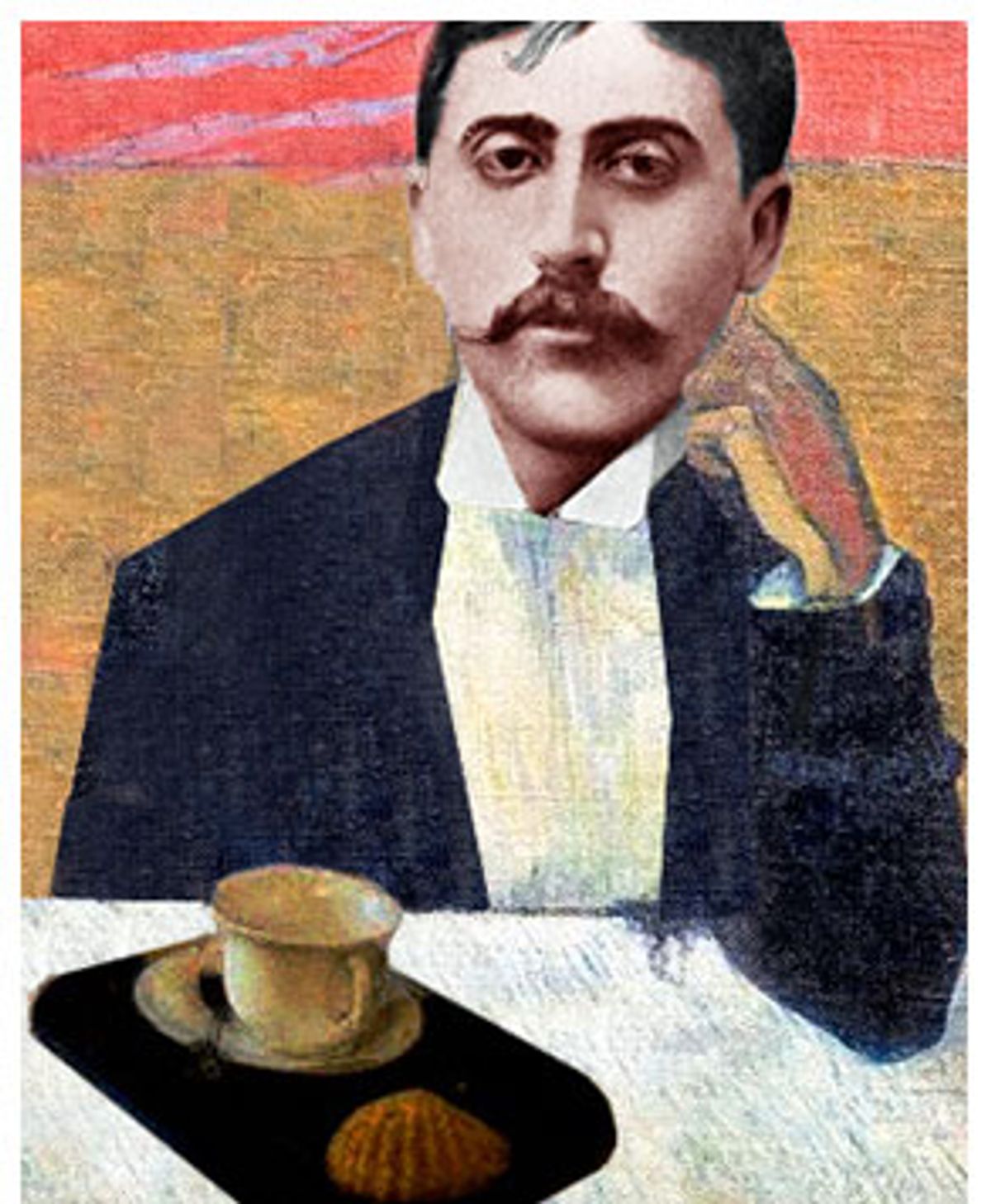

Of course everyone knows that "In Search of Lost Time" begins with a madeleine dipped in tea, except that it doesn't. It begins with falling asleep while reading a book. Someone, "I," a voice who occasionally calls himself "M.," closes his eyes and wakes up a half-hour later, thinking that his book is still in his hands, and by a process of association, begins to think about all sorts of things: the time, an imagined traveler, the comfort of his bed. He sleeps again and is reminded of earlier nights and long ago dreams. The first event he relates is one that happens to have been singular in what seems to be a lonely childhood; unable to sleep and longing for his mother, he is discovered on the stairs by his parents as they go up to bed after a late evening of socializing with their neighbor, Swann. M. expects to be disciplined ("Too late: my father was upon us. Instinctively, I murmured, though no one heard me, 'I'm done for!'"), but he is not. The normally strict father is sympathetic and merciful, and suggests that M.'s beloved mother spend the night with the child.

In order to pass the time, she reads him a novel by George Sand; already his literary sensibility is at work -- "Beneath the everyday incidents, the ordinary objects and common words, I sensed a strange and individual tone of voice." And so have you. Fifty-five pages in, and something has happened. In 10 more pages, you will have done your first day's reading without getting to the madeleine, but Proust's rhythm is well established. It is, let's say, andante: measured, conversational, even ordinary, but seductive and intimate. And that constitutes his promise for all of the 4,200 pages left to go -- his seven volumes will be seductive, intimate, measured and conversational in a way that was unprecedented in the novel of his day and unmatched since.

Sixty-five pages a day is a good goal. Devoting less than an hour every day to "In Search of Lost Time" hardly gets you in the mood, and devoting more than an hour and a half a day for over two months might interfere with your other responsibilities. At the very least, you have to build up some momentum, but not be tempted to skip. (I skipped four pages in the fifth volume when I felt he was being repetitious in his complaints about his captive, Albertine.) Since "In Search of Lost Time" is a story and an essay on what stories mean, skipping sections quickly turns into stopping altogether as you lose the thread of his argument and the relationship of his argument to his story. Besides, there is no way to imbibe his "strange and individual tone of voice," both the Proust-ness of it and the Frenchness of it, without prolonged exposure.

Proust's seven volumes ("Swann's Way," "Within a Budding Grove," "The Guermantes Way," "Sodom and Gomorrah," "The Captive," "The Fugitive," and "Time Regained") form a cycle. They are not, though they pretend to be, Proust's memoir. Many significant facts have been changed to enhance the effect of the novel, in order for it to seem, to the author and the reader, to actually recapture the past -- that is, Proust's childhood and the ambience of pre-World War I France. Here is where the madeleine comes in. Shortly after telling about his single night of bliss with his mother, he recounts how it was a family custom to visit his elderly great-aunt on Sunday afternoons. As refreshment, she often offered her visitors madeleines and cups of lime-flower tisane. When, as a young man, M. happens to enjoy this combination again, a sense memory of visits to the long dead great-aunt returns to him. As he gets older, and the volumes of the novel progress, he despairs of making anything of his life and his literary aspirations until several repeated instances of this effect show him how he might portray scenes and senses from his past with enough intensity to go beyond memory, and therefore beyond loss, grief and sadness. In the last volume, he tells how three sense memories in a short space of time motivate him to finally get started, and to produce the seven volumes you have beside your bed.

M. is a friendly fellow, and the past he wishes to recapture is a possibly unique period of European and French history -- the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As you progress through "Within a Budding Grove" you will certainly be able to picture it when you think of all the Matisse, Pissarro, Cezanne, Toulouse-Lautrec and Monet paintings you have ever seen. The light is bright, ocean and sky are everywhere, the human figures are beautifully dressed, and that astonishing combination of lush vegetation and stone buildings that is the French countryside is constantly in your mind. Here are the mirrored cafes and there is the flashily attired army on parade, and M. and his friend Albertine even see a hot-air balloon. But after all, M. is French, and closely related, in a literary sense, to the Marquis de Sade on one side and Honoré de Balzac on the other.

In Paris, there is society -- which M. investigates at length in Vol. 3, when he becomes something of a protégé to a very wealthy and aristocratic neighbor, Madame de Guermantes. By this time, M. is in his early 20s. At first he is fascinated with everything that Madame de Guermantes stands for in French society and French history. Her family is older and more aristocratic than that of the king, or, indeed, of any king. Kings and queens litter her get-togethers and she does them the favor of being kind to them, even though she prefers the company of M. She laughs at her own lineage and prides herself on being modern and ordinary, but M. does not let you forget the lands and the architecture that Madame de Guermantes is the human embodiment of. You feel a bit privileged to be at her parties, in fact.

And then there is love, which M. explores by imprisoning his beloved Albertine (who is based not on a girl but on a man Proust loved named Agostinelli) in his house in Paris (Vol. 5) and keeping her until she manages to escape and run away (Vol. 6). It is clear from the beginning that M. is ambivalent about Albertine. When he meets her, she is part of a larger group of girls who are breezy, active and liberated. They play tennis and ride bicycles, perhaps have lovers, and perhaps are each other's lovers (M. can never decide). He chooses Albertine out of the group almost by chance, but once he has chosen her, he becomes obsessed with her, while also doubting whether he can marry her, or, indeed, marry at all. He lures her to his Paris maison while his mother is away in the country and keeps her there, partly by promising her marriage and partly by giving her gifts. Whenever she acts trustworthy and affectionate, he is put off and grows bored. Only when she arouses his jealousy does he actually experience love (remember, this is a book about a very young man). During this section, you might want to take a break. I did, of about a week. I read "R Is for Ricochet," by Sue Grafton.

M. also explores ideas of love by spying upon the homosexual encounters of many of his male friends and discovering what he soon realizes is a broad and deep underground of ruling-class homosexual connections partially concealed by wealth, marriage, costume, parties and politics. If "In Search of Lost Time" is undeniably about everything that passes through the consciousness of M., one of those things is sex -- what he feels about it, how he gets it, who else seems to be getting it, what it means to individuals and to social networks, whether it is worth it, what is more interesting and less interesting, and what it makes people do that they otherwise might not do. He seems to agree with the opinion that the Marquis de Sade expresses in the 18th century novel "Justine," that woman are for making economic, social and familial liasons; what men really want is to be buggered, or whipped, by the lower orders.

But, as I say, M. is a narrator of great charm. By the time you get to his "homosexual agenda," many days into your reading of the novel, it will not seem that he is trying to persuade you of anything, only that he is reporting what he sees and thinks and that his greatest desire is to report faithfully and truthfully. As with all novels, you may take it or leave it. Only those who take other people's private sexual choices as personally threatening (and he portrays those types of boors from time to time, the blind, narcissistic and truly self-centered who don't have the capacity to hear or appreciate the nuances of the "strange and individual tone of voice" that is the pleasure and fascination of great literature) might want to quit reading at this point.

It is important that you go about your business while you pursue your reading project. You have to take M. with you on planes and trains and into hotels and to the dentist's office and into your child's piano lesson. "In Search of Lost Time" will not have its full effect if you sequester it. It must diffuse into your life, color every place you go and every scene you look at with its own tints. When you lift your eyes to glance into your own backyard, you want to do so with the sight of Albertine in your mind, quiet in her own chamber, forbidden to awaken M. too early in the morning; or the sight of M.'s friend, Saint-loup, stepping athletically over the backs of banquettes in a mirrored restaurant in Paris, making his way to M., who is sitting eating his supper; or the sight of Madame de Guermantes in one of her elegant turn-of-the-century Fortuny costumes and her red shoes. You want to listen to M.'s quiet voice in your head even while the news is on or while the dog is barking at the arrival of the UPS man. Seventy days in a row to spend with one narrative sensibility is a long time, but after you are finished, it will seem as though you were with him for years and are with him still.

Biographies of Marcel Proust make him out to be an odd man, who lived in a cork-lined room and worked by night for most of the latter part of his life, but M., his narrator, goes on so eloquently and at such length that it ceases after a while to be tempting to diagnose him. He almost pronounces his own diagnosis at the very beginning, right after his mother stays with him for that one night -- if she had stayed away, if they had disciplined him, maybe the twin indulgences of love and literature would not have come to have such a power over him. In the course of his seven volumes, M. hints at efforts the family made, and he made, too, to render him more productive and employable. He goes for cures. He takes too much care of himself. He nearly goes bankrupt buying things for Albertine. He knows he is, and in some sense has always been, a disappointment to his parents. But M.'s sensibility is so fine and so unfiltered that diagnosing him is forgotten in favor of observing him as he observes himself observing everyone around him. His sense of discrimination is robust; his eye is keen; his literary being is abundance itself. He is a man too busy to mourn because he must re-create what is no longer.

Shares