I'm embarrassed to admit it, but I didn't give a shit about getting married until George W. Bush told me I couldn't. My partner and I were in one of those "dignified" gay relationships, the kind whose very longevity triggers smiles of amazement in straight people. We had all our appliances; we were jointly leveraged; and because we were the fathers of two rampaging boys, we knew that neither of us could ever leave without the other putting a bounty on his head. Who needed a fucking ring to keep us in one place?

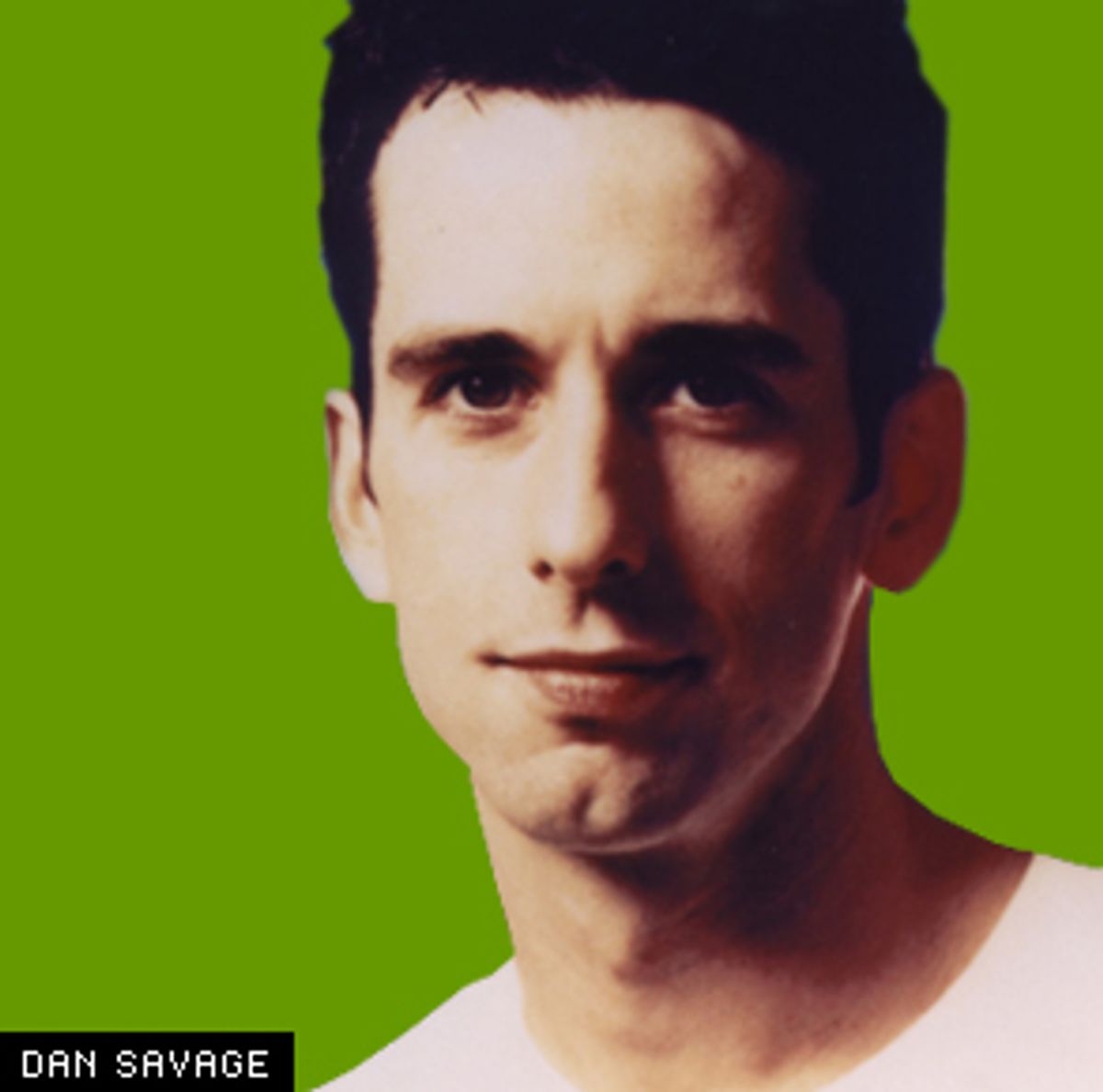

But as Dan Savage says in his fractious, uneven, ultimately moving memoir-screed "The Commitment," "Being told we can't is making a lot of homos wanna." So it was with this homo. The idea that someone could deny me a basic right of citizenship -- even go so far as to try to write me out of the Constitution -- was enough to make me sit up and notice this right, even though I (and my purported representatives in the national gay-rights movement) had never really paid it much attention before.

And at first, I could see gay marriage only through the prism of its enemies. It seemed to me that the best reason to marry was to piss off, in one stroke, George W. Bush, James Dobson, William Buckley, Ann Coulter, Fred Phelps and the pope. There was a certain luster to that; a glamour, even. But when I thought about it, I realized I could just as easily piss them off by giving out free condoms or morning-after pills or voting Democratic or skipping church -- or going to church -- all of which would entail significantly less expense and taffeta than a wedding. Regardless of whom I angered, what would I gain? In today's America, why should any gay man or woman (outside of Massachusetts) get married? Would it be an act of revolution or just volition? Would it bear a public or strictly private meaning? And would I have to buy a tux?

That's just it, you see. The debate is being waged from pulpits -- holy and secular. Voices are raining down on us, some of them shrill, some (Andrew Sullivan, most notably) eloquent -- all speaking in abstract cadences because they're trying to define an institution that has barely begun and, in some quarters, may never exist. What we need, clearly, is someone to field-test these abstractions, to show us what gay marriage actually looks, feels, sounds, smells like in these legally and culturally proscribed times.

Well, OK, I didn't know we needed that until I read "The Commitment." But having realized we did, I can now see that Savage was just the guy to fill this peculiar niche in our national discourse. In addition to penning the sly and scabrous sex-advice column "Savage Love" (his most sustained work -- an underground comédie humaine), Savage has, in his last two books, staked out the front lines of cresting social movements and given us a view from the trenches. "The Kid" was a funny, achy, refreshingly unsentimental look at how Savage and his boyfriend, Terry, went about acquiring a baby. (It was also an ur-text for a whole generation of gay parents.) "Skipping Towards Gomorrah" was a takedown of William Bennett and the virtuecrat movement in which Savage (not always convincingly) went about committing or witnessing all seven of the deadly sins in order to show how little harm they posed to sinners or the surrounding populace.

So it stood to reason that, if anyone were going to scout the terrain of gay marriage, it would be Savage -- although he spends most of the book wondering if he should venture in at all. On the face of things, he and his partner (a word Savage hates) have no particular need to tie the knot. They have long ago graduated into the "dignified" category of relationships. They are living comfortably in a politically liberal community in the Pacific Northwest; Savage's career is singing along; Terry stays home with their 6-year-old son, D.J., who likes skateboarding and Iron Maiden.

But their 10th anniversary is fast approaching, and they want some way of commemorating it (Terry suggests tattoos) without, of course, putting any jinx on the relationship and, oh, maybe they could have some kind of ceremony or maybe they shouldn't have any ceremony -- and through this valley of indecision gusts an alarming new prospect: Why don't they get married?

This idea is most vigorously propounded by Savage's mother and most vigorously resisted by Savage's son, who announces that, if his dads persist in this course, "He's not coming to the wedding. He'll come to the party after the wedding -- provided there's cake -- but there's no way he's going to the ceremony." (Boys, he insists, do not marry boys.) And even Savage is skeptical: "I can't see going to Canada or Massachusetts to marry Terry when all we're going to get for our trouble is the jinx and a scrap of paper that would be worthless in the state where we live."

And nevertheless -- is it fate? family pressure? his publisher? -- he does inch closer to matrimony. And for me, the best part of reading "The Commitment" is seeing Savage come up against all the hurdles -- internal and external -- that have put me off that institution. And if he doesn't exactly clear them, not every time, he at least negotiates them in a plausible manner. Beginning with:

Hurdle 1: The "Notes on Camp" thing

Camp, according to Susan Sontag, is "failed seriousness." At the risk of being rude, may I suggest this perfectly describes the average commitment ceremony? Those handsome men (and women) in their matching white tuxedos and boutonnieres have always looked absurd to me -- like schnauzers in sweaters. The more seriously they take themselves, I'm afraid, the more ridiculous they seem. And no wonder, says Savage: The rituals they're enacting are "pregnant with heterosexual symbolism." He asks: "Wouldn't two gay men walking down the aisle together look just as silly as two gay men doing the foxtrot?"

Solution: Throw a big Chinese New Year party. Invite everyone you know. Wear a T-shirt and jeans. If something happens at or before or after the party, so be it. No tuxes.

Hurdle 2: The baby-with-the-bathwater thing

I've always felt that my "dignified" gay relationship really does have a certain dignity, which is largely the product of surviving in the face of society's vast indifference. I don't think I could have expressed it, though, as well as Savage does: "Unlike heterosexuals, we had to do the hard work of building a life together in order to be taken seriously, something we did without any legal entanglements or incentives. Without the option of making a spectacle out of our commitment -- no vows, no cakes, no rings, no toasts, no limos, no helicopters -- we were forced to simply live our commitments. We might not be able to inherit each other's property or make medical decisions in an emergency or collect each other's pensions, but when our relationships were taken seriously it was by virtue of their duration, by virtue of the lives we were living, not by virtue of promises we made before the Solid Gold Dancers jumped out of the wedding cake at the reception." If gay men start letting in the wedding cake and the Solid Gold Dancers, Savage suggests, "something else will be lost, something intangible, something that used to be uniquely our own."

Solution: Get two cakes. Don't hire dancers. Trust that the "something intangible" will still be in place after it's all over.

Hurdle 3: The gay-membership-card thing

To a certain class of gay theorist (Edmund White, say), the whole idea of aping traditional institutions like marriage is unredeemingly heterosexist. And in its current frangible condition, marriage might not be something we should aspire to, anyway, and even if we did take the plunge, maybe we wouldn't be so hot at it? Savage is even more pessimistic: "I, in fact, fully expect us to be worse at it. With so many homos forced to sit at dinner tables and in pews listening to parents and preachers dismiss same-sex love as diseased or nonexistent, it's highly likely that thousands of immature and/or insecure homos will marry to prove to themselves, to their families, and to their preachers that gay love is so real."

Solution: ... well, this is how Savage's mother responds when Terry makes something of the same point:

"Jerkos have told you both that you're not worthy of marriage. You could flip off the jerkos by doing the right thing and getting married anyway, but you're way too clever for that. So you've decided to flip them off by refusing to get married. You say it's 'acting like straight people' ... You should stop worrying about acting like straight people, Terry, and start acting like the person I know that you are -- a serious, grown-up, responsible person who should be mature enough to make a serious commitment to the person he chose to start a family with, just like his parents did."

And with that, the final hurdle is cleared. Or is it?

Savage's books tend to be ungainly constructions, and "The Commitment" is no exception. It dawdles, it feints, it repeats itself. The personal and political don't so much interweave as collide. Far too much time is spent on baldly Socratic dialogues between Savage and his siblings. We get long vacations in Saugatuck, Mich., dips into the old gene pool, digressions on cake, sexual-fetish anecdotes -- there are times you'd swear that the only thing driving the book was the book contract. (Savage might be the first to agree.) But, as he always does, Savage locates his target -- just when you thought he'd forgotten it. The fact that he's funny helps. "Anyone who denies the existence of the obesity epidemic in the United States," he writes during a trip through the heartland, "hasn't been to a water park in Sioux Falls, South Dakota." On a New Age wedding: "The only thing worse than organized religion. Disorganized religion." On the music in a Chinese restaurant: "It sounded like a live cat in a George Foreman Grill."

He also has a vein of tenderness, more appealing for being tapped so sparingly. It comes out particularly in his descriptions of D.J.: "the rich, humid scent of your child, the way your child's hand feels resting in your own, the trusting, contented weight of your child sitting in your lap while you read or watch TV." Without revealing too much of the climax, I will say only that it takes place in Canada, that D.J. plays a prominent and hilarious role in it, and that he undertakes the same useful function that 6-year-olds have been performing since the dawn of Family: mocking the po-faced adults who have inexplicably been put in charge of them.

"The Commitment" was written, of course, at a time of unprecedented political retrenchment. Gay-marriage opponents, energized by the Karl Rove goon squad, have rammed through constitutional amendments in more than a dozen states. They've deleted homosexuality from textbooks, pulled gay books from library shelves, torpedoed domestic-partner benefits, denied gay parents the right to adopt. (My own neighboring state of Virginia has banned not just civil unions but any "partnership contract or arrangement between persons of the same sex purporting to bestow the privileges and obligations of marriage.") The proliferation of these "Nuremberg-lite laws" imparts an even whiter heat than usual to Savage's prose. And unlike the resident scolds of the gay movement (Larry Kramer springs to mind), Savage's rage actually makes him a better, more coherent writer. He's especially good at isolating the bait-and-switch tactics of the religious right: "From Anita Bryant through early Jerry Falwell, gay people were a threat because we didn't live like straight people. Now we've got Rick Santorum and late Jerry Falwell running around arguing that gay people are a threat because some of us do live like straight people."

"The problem for opponents of gay marriage," Savage writes, "isn't that gay people are trying to redefine marriage in some new, scary way, but that straight people have redefined marriage to a point that it no longer makes any logical sense to exclude same-sex couples. Gay people can love, gay people can commit. Some of us even have children. So why can't we get married?"

No reason, but as Savage knows, reason doesn't enter into it. You can beat the opponents of gay marriage on every conceivable debating point, and they will retreat behind the carapace of "faith," which is really their projection of how things should be -- their prejudice. And since there is prejudice enough on both sides, we have arrived at an age of really horrifying division: people shouting across a gorge and hearing only the echoes of their own voices. And ultimately, Savage's book, far from changing any minds, will become just part of the noise.

Time, I suppose, may erode the animosities, the certainties. Until then, orthopraxy will have to do what orthodoxy can't. Which is to say, gay men and women will have to go on making their private decisions in the hope of someday reaping a public concession -- which we may not live to see.

A few years back, Don and I bought rings at a Provincetown, Mass., gift store. Titanium bands with a narrow gold stripe. We put them on without a word of explanation to anyone. We went to dinner at Bistro Bis and we murmured a few silly words -- nothing resembling a vow -- and we said nothing more.

I'll add only this: Don never takes that ring from his finger. (Economics, partly: He lost the first one and doesn't want to have to buy another replacement.) I feel it sometimes in the middle of the night, when he rolls toward me in bed. A chaff of metal against my cheek or my shoulder. It never scrapes too hard, but even in a state of half-consciousness, I marvel at the thing's resilience. That it can go on, even in our deepest slumbers, attesting to us.

Shares