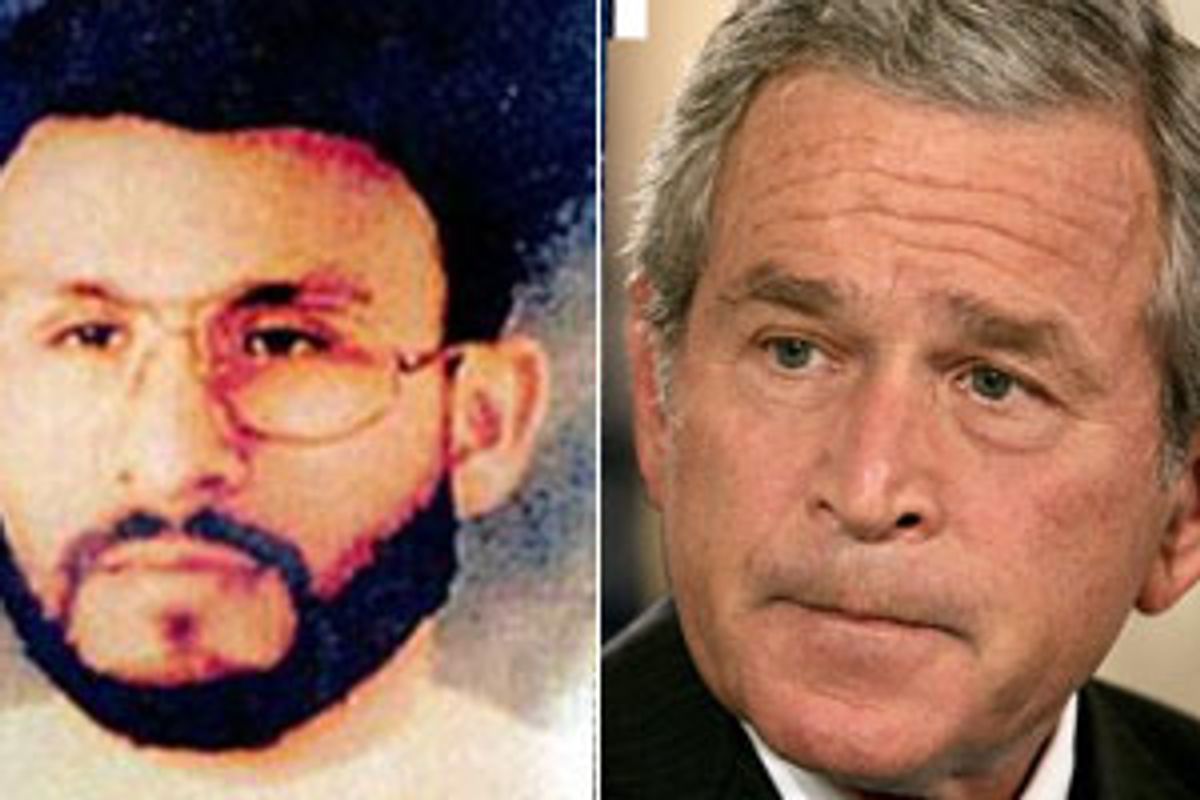

Harsh interrogation works -- that's the argument President Bush made on Wednesday even as he announced that al-Qaida operative Abu Zubaydah and 13 other alleged al-Qaida operatives will be transferred to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, to face trial. Acknowledging for the first time the existence of secret CIA prisons where the 14 men had been held, Bush claimed that the extreme interrogation techniques used on Zubaydah, whom he called "a senior terrorist leader," and others in the "war on terror," were justified. Bush said that Zubaydah, under the pressure of what Bush referred to as the CIA's "alternative set of procedures," had given up information that proved vital to the United States.

But Pulitzer Prize-winning author Ron Suskind paints a more complicated picture of Zubaydah. In one of the most hotly discussed sections of his book "The One-Percent Doctrine," Suskind reveals that at least one top FBI analyst considered Zubaydah an "insane, certifiable, split personality" and that he was mainly responsible only for logistics like travel arrangements. According to Suskind's reporting, the interrogation methods used on Zubaydah -- waterboarding and sleep deprivation, among others -- only yielded information about plots that did not exist.

Salon spoke with Suskind about how the Bush administration has tended to oversell Zubaydah's significance and why sophisticated "soft" interrogation techniques have been the most effective.

What did you think of the president's speech?

Well, I don't think that the president contradicted anything that's in the book. I say in the book that we did get some things of value from Abu Zubaydah. We found out that "Muktar" -- the brain, that's what it means in Arabic -- was Khalid Sheik Mohammed. That was valuable for a short period of time for us. We were then able to go through the SIGINT [signal intelligence], the electronic dispatches over the years, and say, "OK, that's who 'Muktar' is." Zubaydah, of course, is showing up on signal intelligence as Zubaydah.

Also, we essentially said, "You've got to give us a body, somebody we can go get," and he gave us [Jose] Padilla. Padilla turned out to not be nearly as valuable as advertised at the start, though, and I think that's been shown in the ensuing years. So that's what we got from Zubaydah.

At the same time, I think we oversold [Zubaydah's] value -- the administration did -- to the American public. That's indisputable. As well, what folks inside the CIA and FBI were realizing, even as the president and others inside the administration were emphasizing the profound malevolence and value strategically to the capture of Zubaydah, is that Zubaydah is psychologically imbalanced, he has multiple personalities. And he was not involved in various events that we thought he was involved in. During various bombings in the late '90s, he was not where we thought he would be. That's shown in the diaries, where he goes through long lists of quotidian, nonsensical details about various people and what they're doing, folks that he's moving around, getting plane tickets for and serving tea to, all in the voices of three different characters; page after page of his diary, filled, including on dates where, I'm trying to think, it was either the Khobar Towers or the Cole, where we thought he was involved in the bombing and he clearly wasn't.

So that's the real story of Zubaydah, more complicated than the administration would like, and maybe more complicated than the president at this point feels comfortable saying in an election season. It's one of the many instances where you could shine a light through this prism and see an awful lot about some of the dilemmas of the war on terror.

In the case of Zubaydah, when it comes to some of the harsh interrogation tactics he was put through, what occurred then was that he started to talk. He said, as people will, anything to make the pain stop. And we essentially followed every word and various uniformed public servants of the United States went running all over the country to various places that Zubaydah said were targets, and were not.

Ultimately, we tortured an insane man and ran screaming at every word he uttered.

And what do you think of the interrogation procedures the president described?

The fact is that the history of interrogation shows that you do not do particularly well when you confirm expectations, when everybody plays their preordained role. In this case, al-Qaida operatives are trained to believe that the United States, and representatives of the U.S., are bloodthirsty mobsters who will dismember and disembowel. The fact is, when we use harsh techniques we essentially say, "We are going to confirm your expectations."

What has largely worked in all the interrogations, what we got -- and in many cases it's not very much -- but whatever we got, for the most part occurred because we were, let's just say, a little more clever than that. Instead of going medieval, which is the tactic our enemies here embrace, we essentially find a way to confuse their expectations. In many cases, just by treating them as human beings we have created an environment where we get what we so desperately need, which is information that might help save American lives.

That's the key. The key is to not give in to anger, but to do whatever works best. There's clearly been a learning curve on that; some of the harsh techniques used early on have been I think largely abandoned because they didn't work.

That's what we're finding today, in terms of these competing press conferences. The president vs. the Pentagon; the Pentagon folks are listing out two dozen or so techniques that we'll use, which are fairly tame. Going forward, the president is saying, well, we got some valuable things from using these harsh interrogation techniques. Ultimately, one is message, the other is reality. This is the way the White House does a very careful bit of calibration to say that we thought at the beginning it wasn't quite right in terms of using harsh or extra-legal methods, many of them qualifying as torture, on the folks who've been captured.

What techniques have they dropped?

Death threats, waterboarding, profound deprivation issues, heat, cold, denial of medical attention -- those are now abandoned.

One of the dark moments in the so-called war on terror, as I disclosed in the book, along with all the other stuff, is that we threatened Khalid Sheik Mohammed's children to get him to talk. According to those involved in that incident, he pretty much looked them straight in the eye and said, "Fine, they'll be in a better place with Allah." Once you threaten someone's children there's pretty much nowhere else to go in terms of building the kind of relationship where they at some point tell you things that you really need to hear.

The president said today that Zubaydah was a "senior terrorist leader" and a "trusted associate of bin Laden," and that the "intelligence community believes he had run a terrorist camp in Afghanistan where some of the 9/11 hijackers trained, and that he helped smuggle al-Qaida leaders out of Afghanistan after coalition forces arrived." What do you think of that characterization?

Zubaydah was not involved in key operational planning for al-Qaida. He was involved largely in logistics.

So you think describing him as a "senior terrorist leader" and a "trusted associate of bin Laden" is an overstatement?

I think, again, that the president is overstating a little less than the overstatements when Zubaydah was first captured, but nevertheless, still a bit of an overstatement.

The president also talked about Zubaydah giving away "what he thought was nominal information -- and then stopp[ing] all cooperation," and then they used these harsher tactics and he gave up what the president said was "information on key al-Qaida operatives, including information that helped us find and capture more of those responsible for the attacks on September the 11th. For example, Zubaydah identified one of KSM's [Khalid Sheik Mohammed] accomplices in the 9/11 attacks -- a terrorist named Ramzi bin al Shibh. The information Zubaydah provided helped lead to the capture of bin al Shibh. And together these two terrorists provided information that helped in the planning and execution of the operation that captured Khalid Sheik Mohammed."

Zubaydah gave us the information he gave us because, in using softer techniques, we convinced him that his religious belief in predetermination was such that he believed that he wasn't killed, but captured, when other people died, obviously, that he was wounded and captured for a reason, and the reason was to give us some information. That was why he gave us some information, that was the rationale he used. That was what one would consider more sophisticated, "soft" interrogation techniques, where we got the stuff of value.

So the stuff about bin al Shibh, that came through softer interrogation tactics?

Bin al Shibh, no. I'm not talking about the bin al Shibh stuff or the KSM stuff. Ultimately, we ended up getting the key breaks on those guys, KSM and bin al Shibh, from the Emir of Qatar, who informed us as to their whereabouts a few months before we captured bin al Shibh. That was the key break in getting those guys. KSM slipped away; in June of 2002, the Emir of Qatar passed along information to the CIA as to something that an Al Jazeera reporter had discovered as to the safehouse where KSM and bin al Shibh were hiding in Karachi slums. He passed that on to the CIA, and that was the key break. Whether Zubaydah provided some supporting information is not clear, but the key to capturing those guys was the help of the Emir.

So considering the parts of the speech we've just discussed, how do you feel about it generally now?

The president is trying to stick to message here, and it's not easy, because the facts are more complex, and in some cases contradict the claims of the U.S. government. This is the White House trying to do a bit of a recalibration as to the views and strategies in terms of interrogation and the handling of prisoners without having to admit that it made mistakes early on and maybe even learned something along the way.

Shares