David Lynch should come with a personal Surgeon General's warning: If you're the right kind of ex-smoker with a vaguely bohemian past, hanging out with him can make you furiously want to light up.

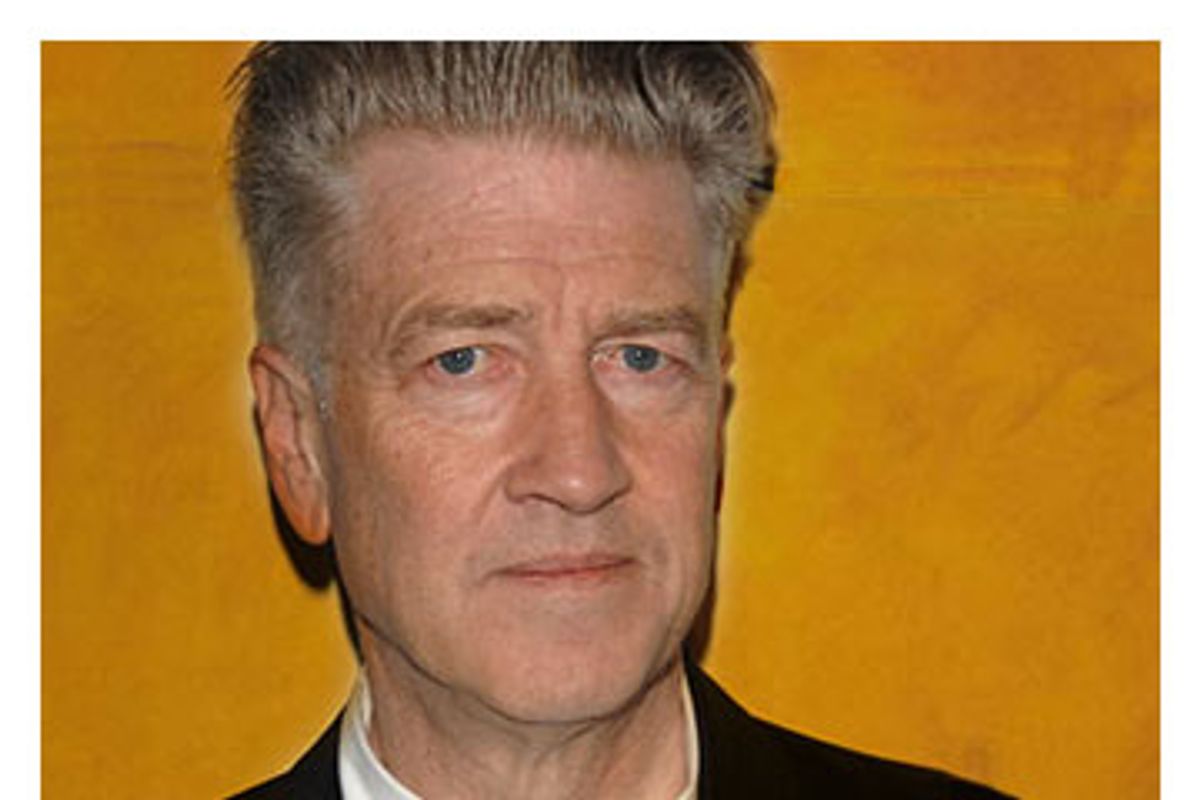

I avoided smoking when I met Lynch the other day in a freezing artists' loft overlooking the West Side Highway in New York, but the Lynchian mood of total enthusiasm and commitment, saturated in caffeine and nicotine, was contagious in other ways. (Listen to a podcast of the conversation here.) At age 60, Lynch is a long way from being the enfant terrible of American film. His hair has gone completely white and his face is seamed. He looks and sounds like the eccentric, charismatic art or drama teacher at a Middle American high school (Lynch grew up in Missoula, Mont.), the one the oddball kids flock to. He was dressed like an undertaker, in a starched white shirt buttoned to the neck and a black coat that reached his knees.

The man who made "Eraserhead" and "Blue Velvet" and "The Straight Story" and a notorious, doomed version of "Dune" has been through Hollywood and come out the other side, more of an outsider now than he's ever been. After making the international cult hit "Mulholland Drive" in 2001, he could easily have gone back to a major or "mini-major" studio and commanded an eight-digit production budget. Instead, he spent almost four years with Laura Dern, a large supporting cast and an off-the-shelf digital video camera (the Sony PD-150, for you equipment mavens), making up a movie as he went along.

By Lynch's own account, he began writing and shooting scenes without knowing how or even whether they were connected, and only late in the process began to stick them together into something resembling a narrative. And the resemblance, one has to say, is pretty vague. The resulting movie is called "Inland Empire," although I don't think any of it takes place in the suburban desert valleys of southeastern California that bear that name. It might be about a Hollywood actress named Nikki (Dern), married to a rich but sinister Polish aristocrat, whose comeback project turns out to be a film haunted by a Gypsy curse, and who suffers a psychotic breakdown (or, if you prefer, travels through a portal into an alternate reality or two).

Trying to force Lynch's films into some unitary interpretive structure has rarely been helpful, and it's even less so here. No plot summary can capture all the salient elements of "Inland Empire" -- the hopscotching from Los Angeles to the snowbound city of Lodz in Poland; the cryptic fragments of thriller; the interpolations from "Rabbits," Lynch's Dada-style Internet serial; the eerie dance number featuring a bunch of Hollywood Boulevard hookers performing the Locomotion. More than anything else, "Inland Empire" is about its own haunting auditory and visual experience; in her marvelously written review, New York Times critic Manohla Dargis argues that it's best understood as a series of crumbling, glorious interior spaces, the kinds of locations Lynch has always employed to powerful and mysterious effect.

I'm on record as expressing exhaustion and frustration -- as well as fascination -- with "Inland Empire" after seeing it at the New York Film Festival, and there's no need to repeat all that. Talking to Lynch (and also to Dern and costar Justin Theroux) reminded me that no single viewer's response is sufficient or explanatory when it comes to a movie like this. Lynch is trying to push beyond the boundaries of 99 percent of contemporary cinema, trying to reinvent, or at least re-access, the revolutionary cinema of his idols Bergman and Fellini. While I remain skeptical that there's much of an audience in 2006 for a film this deliberately abstruse, there can be no doubt about the nobility of the effort.

Lynch's company will be distributing "Inland Empire" entirely on its own, without help from any major studio or indie distributor. When I met him, Lynch had just flown in from a promotional screening in Boston, and had only a few minutes to talk to me before heading for another at Manhattan's IFC Center. One of his assistants told me that setting up a traditional media junket at a midtown Manhattan hotel would have cost $50,000, so instead reporters met Lynch, Dern and Theroux in a donated, and apparently unheated, arts space on 11th Avenue.

The experience was not unlike a scene in "Inland Empire" itself. You entered through an unmarked red door on the wind-blasted avenue, and ascended a long, dim and steep staircase with portable closet lights strung along the floor. I sat down with Lynch in a stark but cheerful studio space, hung with abstract paintings in bright primary colors. It was a perfect setting, not ironic in the slightest.

Himself a former painter, David Lynch is an artist to his bones, and his core audience will always be the art-school types, the film geeks, the true believers. But Lynch has an artist's purity and optimism, and perhaps naiveté as well. James Joyce apparently believed that ordinary, bourgeois 20th-century readers would intuitively understand the stream-of-unconsciousness narrative of "Finnegans Wake," a book long since abandoned to the academic priesthood. Lynch talks in similar terms about the ponytailed 14-year-olds he hopes will flock to see "Inland Empire."

If there still are ponytailed teenagers in Middle America, outside the patented small towns of Lynch's imagination, no less likely audience for this film can be imagined. On the other hand, if he can get them sufficiently stoked on his David Lynch Signature Cup coffee blend -- as I told him, this is by far the most marketable idea he's ever had -- then anything is possible.

So, David, you've got this new film, "Inland Empire," and you're basically putting out the darn thing yourself. Most of the time when somebody makes a movie and we get to see it, either a big company in Los Angeles puts it out or a small company in New York puts it out. You don't have either of those.

No. I've done that before. Any one of those companies has a team -- one person does this thing, one person does that thing. So I have a team; it's just not at a studio.

And it's a lot smaller. Can your team really do all the things you need to do, to get people to come see your movie?

You know, money is great. But there are things that can be done these days without spending a bunch of money. A lot of it's tied to the Internet. Distribution is changing. The people at distribution companies are human beings. Sometimes they get it right, sometimes they don't. There's no real experts. There's no studio head that always picks a winner. So the bottom line is, in the past I've gotten advances and never seen anything beyond the advance. [Long pause.] There's, um, no guarantee I see anything this way either. [Laughter.] But at least it'll be my fault. I think it's the way things are going. Advances are going down for films. There's no big payoff anymore. This has already all happened in the music business, and now it's starting in films. It's better to go this way.

And you're all set to put out the film on DVD when the time comes?

Oh, yeah, yeah.

I'm just guessing you have a lot of great extra stuff for the DVD.

People love extra stuff. And this is a heartache to me. Because the film is the thing! But the film isn't the thing [on DVD]. I mean, it is the thing, but people want Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. Do you know what I mean?

That's interesting. I do sometimes feel like the film itself recedes into the background on DVD. People get so interested in the back story, the peripheral stuff. You know, if you want to watch "Citizen Kane," watch "Citizen Kane"!

Yeah. Beginning, middle and end. At least once. And then get going on the extras.

OK, let's try to talk about your movie. I know you have your reasons for not discussing things like intention or meaning. But you're asking people to go see a three-hour film by David Lynch. So what can you tell them? What's it about?

A woman in trouble.

Right. Well, that's short and pithy. What else can we say about it? That woman is played by Laura Dern, who's playing, I don't know, either three different characters or one character split up three ways. It takes place in a lot of different settings, in California, in Poland, maybe other places. It's partly set in the film industry, and it feels partly like a commentary on the film industry.

[Lynch smiles but doesn't respond.]

Well, look. With or without your help, you know people are going to devote tremendous energy to figuring it out and piecing it all together. On Salon, there was a ferocious discussion about "Mulholland Drive" between our readers and a couple of writers, trading theories and trying to figure out what was going on in that movie. Are you OK with that kind of thing?

Absolutely! You know, people -- we're all detectives. We all have intuition. We're all sensing more than what meets the eye, deciphering things, figuring things out. So beautiful for the human being. It's part of it, it's part of us. Some films can be great, they're entertaining, you love 'em, but that's it. You're on to the next thing. And others, you can roll 'em around, you can think about them, live with them. And if you like that world that you get to go into, that's a beautiful thing. You can visit that world again, and go in and, in a way, get lost, like Chet Baker -- "Let's Get Lost." You get lost in a dream, and there's indications of things, that you can put it all together. It's all there.

OK, that's a good, cryptic David Lynch answer. I'll run with that.

OK. [Laughter.] That was completely straight-ahead, man.

I've heard you say before that you personally like to experience movies that are like dreams.

Well, that have room to dream. That get you going on what you could say was a dream.

So what movies have done that for you, in your life?

Well, like, Bergman and Fellini. Hitchcock, in a way. Kubrick. A lot of film directors -- Billy Wilder -- they make such a place, such a world, that you want to go there again and have that experience. It's an experience and a mood, and some abstractions that you can't necessarily put into words for your friends, but you say, "You have to feel, to experience that. You have to go in there and experience that. It'll make you dream."

This is a tricky one, maybe. You don't want to mess with my understanding of your film, and I can respect that. But don't you believe that your subjective understanding of what "Inland Empire" is about -- given that you directed it -- is necessarily more accurate than mine or anybody else's?

Maybe. [Laughter.] But yours is accurate for you, and as valid as anyone else's interpretation. It's like the world around us. We all maybe think we see the same world, but they say that we don't. They say that the thing is, the world is as you are. A lot of people are really, like, say, political. And they'll see films in terms of politics. Other people are into something else, and they'll see any film in terms of that, but it really means in terms of themselves. Their interpretation comes from that. As I say, the analogy is [gesturing at the paintings on the walls] standing in front of an abstract painting. The more abstract it is, the more varied the interpretations. And each viewer standing in front of that painting is getting a different thing. It's hittin' a different system each time. Same painting!

Well, it's my judgment that "Inland Empire" is the most abstract or experimental film you've done, at least since "Eraserhead" and maybe ever. Do you agree with that, and was it part of your intention?

No, my intention -- there's no intention. Ideas come along and you fall in love with them. In some ways that could be right, but it's a different thing. Each film is different, because the ideas are different. My hope is that the 14-year-old girls, maybe with a ponytail, going down the tree-lined streets in the Midwest, embrace "Inland Empire." Get their boyfriends into the theater with them. Have this experience. It would be so beautiful. [Laughter.]

Wow. I can only hope you succeed. Talk about the process of making this film, because I think it's quite different from anything you've done before. When you started shooting, you still didn't know where you were going, is that right?

Exactly. Always, I don't know where I'm going, but by the time I finish writing a script, I know where I'm going. This time, there were just scenes written. A scene written and shot, another scene written and shot. Scene 1 doesn't relate to Scene 2 whatsoever. Then I get an idea for a third scene, and I don't know how these are relating, or if they will ever relate. At this point, I'm just doing this on my own. Somewhere around five, six or seven scenes in, it happens that I see the unification, and a larger thing growing out of it. That would happen in writing a script before, and now it's happening as I'm shooting. Always, when you get one idea that you love, it is like a bait and it draws other things. It's like getting pieces of the puzzle one at a time. If the puzzle is green grass and a blue sky and a house, you get a piece of blue, you get a little thing of green -- you can't even see the grass, it's in the shadow, say, dark green -- and a little bit of roof tile. And you kind of wonder about these things, but then some other ones come, and lo and behold, one day there's the whole thing.

Did this approach change the actors' performances? The fact that they didn't know where they were going?

They talk about that. Not knowing, like, the arc. They've got a term now, it's called an "arc." I know there is one, an arc. [Laughter.] Scene by scene is what you shoot a film with, anyway. You're shootin' this scene and you're working it to make it feel correct. Everybody involved is talking -- action and reaction, rehearsal and talk, rehearsal and talk -- to get 'em to zero in on the original idea that's driving the boat, and working it till it feels correct based on that idea. So scene by scene, it goes that way anyway.

But sometimes they [the actors] know something that's going to happen later. Now, if they know that they are lying in this scene, I don't know if there's some subtle little -- what do you call it in the card game?

A tell.

Right. This way there's no possibility of a tell. It's honestly this scene. I say, "You're you today. You don't know what's going to happen tomorrow." It's kind of interesting to go that way. There was a certain point when I had the future scenes, and so they knew some things that were going to happen, and it became more like the regular way of working.

Do you think that somebody who's trying to impose a single coherent narrative on one of your films is wasting their time, or closing themselves off to the whole experience?

Yes. If I said something beforehand, you mean? If they knew upfront what I thought it meant?

Well, that. But even if they're trying to impose something ...

As they watch? Well, yeah. Many people have said, "You know what? A couple of scenes in, or halfway through, I just said, screw it, I'm just gonna let it wash over me and not worry about it." Honestly, that's the best way. All you've done is you've turned off the intellect a little bit. Other things are still really working, but the thing that tries to make sense of it in a traditional way has surrendered itself. [Laughter.] I think that's kind of beautiful. I think about, you know, like, um, seeing ... [long pause] It's just -- get in that world and let it be.

I think if any of your movies really accomplishes that ...

It's this one. Uh-huh. [Laughter.]

I know you have to go. But this is really important: Tell me about your new line of coffee.

David Lynch Signature Cup. It's the coffee I drink. And I really love drinking coffee.

I've heard that. I wish we had some right now.

Yeah! So it's gonna be sold on the site at first, and then it's going into stores. Yesterday I was at the Brattle Theatre in Boston [actually Cambridge, Mass.], and they want, you know, to put it in the lobby. It would be very cool if it was in art houses. It's a filmmaker's coffee. But a coffee that all people, I hope, will enjoy. It's really good.

Maybe your coffee can help save the art houses of America.

Well, the art houses have got to come back. It's tough going right now. But things go in waves. That's why I'm holding out hope for those 14-year-old girls. I'm not kiddin' you! Hollywood, the blockbuster mentality, has gone around the world killing the art houses, alternative cinema. But it is alive, that cinema! It's everywhere now, but it's hard to see it in the theaters in America. It's hard to see it in the theaters in Europe! So I'm hopeful that this change can occur again, like we saw in the '60s. It would be cool.

You know, there was a time when they said painting was dead. Painting ain't never gonna be dead. No medium is gonna be dead! Infinite possibilities, always surprises coming along. There are not that many surprises in a formula, an arc. Some solid entertainment, nothing wrong with it. But there's room for much, much more. And let's not miss out on the much more.

"Inland Empire" is now playing at the IFC Center in New York and the Brattle Theatre in Cambridge, Mass. It opens Dec. 15 in Los Angeles, with openings in Austin, Texas; Chicago; San Francisco; Seattle; Washington and other cities to follow in early 2007.

Fast forward: Visit "Bergman Island"! The umpire strikes back in "Off the Black"; "Family Law" offers love, Argentine style

My schedule has been too smushed to catch "Bergman Island," documentary filmmaker Marie Nyreröd's interview with David Lynch's No. 1 hero, 88-year-old Ingmar Bergman, on the island home he now plans never to leave again. Suffice it to say I'll find a way to get to New York's Film Forum to catch it this week, if I have to burrow in from the Varick Street subway station, and I know some of you will be with me. (Other engagements should follow.)

Also opening this week is "Off the Black," a subdued coming-of-age picture in a classic Amerindie mode, starring Nick Nolte in one of his crusty local character roles. This time Nolte is Ray, an aging, alcoholic high-school baseball umpire who forges an uneasy friendship with the teenager who vandalizes his house one night. The almost girlishly handsome Dave (Trevor Morgan) is a star pitcher whose team loses a game Ray has umpired, but the poles of their relationship reverse when he realizes that Ray is actually a lonely, sentimental drunk -- who wants Dave to pose as his son at a high school reunion.

Written and directed by James Ponsoldt, "Off the Black" is restrained and graceful, giving us only minimal information about Ray and Dave outside their scenes together. Ray was married and has a real son somewhere, Dave's mom bailed out a few years ago and his dad (Timothy Hutton) can't talk about it, or much of anything else. In fact, I think the movie is so restrained, and holds back so much on conventional plot and characterization, that its emotional impact is severely blunted. Nolte is excellent, I suppose, but we've seen this damaged-American-dude shtick from him before. (Opens Dec. 8 in New York and Los Angeles; Dec. 15 in Chicago, Minneapolis and San Francisco; Dec. 22 in Boston, Philadelphia and Washington; Jan. 5 in Salt Lake City; Jan. 12 in San Diego; and Jan. 19 in Athens, Ga., with more cities to follow.)

More cheerful, but at about the same middle-interest level, is "Family Law," an alternately charming and frustrating comic entertainment from Argentine writer-director Daniel Burman. I'm a big fan of Argentine cinema in general, but this is not up to the recent standard of Fabián Bielinsky's "The Aura," Lucrecia Martel's "The Holy Girl" or Pablo Trapero's "Rolling Family," a vastly superior comedy.

It's great to see Arturo Goetz, one of that nation's finest character actors, playing "Doctor" Bernardo Perelman, a cheerfully cynical Buenos Aires Jewish lawyer, operator and all-around bon vivant. But the film is supposed to be about his relationship with his son Ariel (Daniel Hendler), a repressed, uptight public defender who sleeps with his suit on, and -- as that suggests -- is a lot less interesting than his father. You can say that "Family Law" is sweet-tempered and nonjudgmental, and handles this comic soap-opera material much more elegantly than a similarly themed Hollywood movie might. I guess that's why this is Argentina's official Oscar candidate. (Opens Dec. 8 at the IFC Center in New York, Dec. 14 in Boston, Dec. 22 in Los Angeles, Dec. 29 in Chicago, Jan. 20 in Oklahoma City, Jan. 26 in Seattle, Feb. 9 in Albuquerque, N.M., Feb. 16 in Washington and Feb. 23 in San Francisco. Also available pay-per-view on certain cable TV systems; check local listings.)

Shares