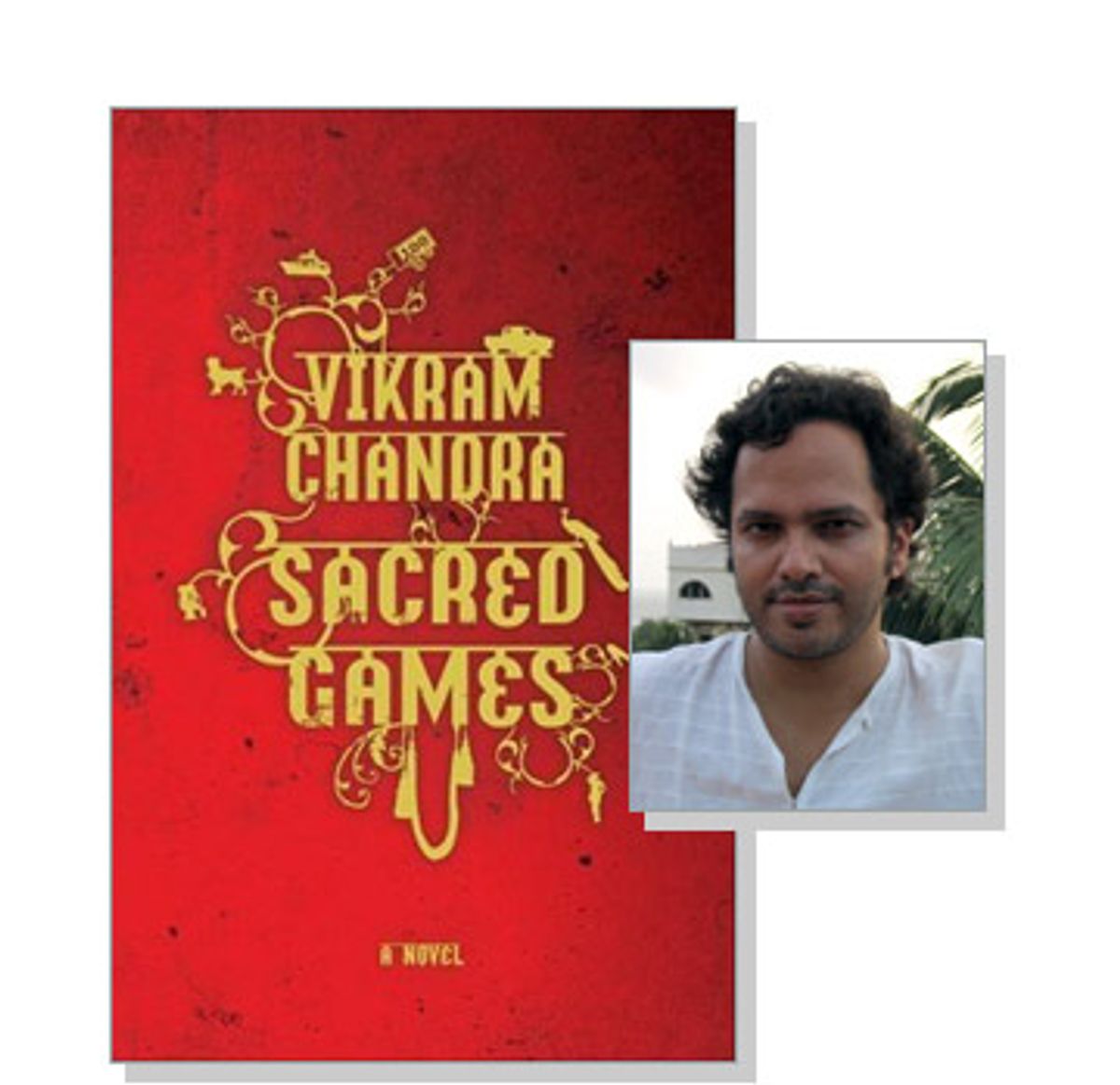

"When a man is tired of London," said Dr. Johnson, "he is tired of life." This, I realized as I turned the 900th page of Vikram Chandra's absorbing second novel, "Sacred Games," is also the theme of the book I'd just finished. Like all big, fat Indian novels, "Sacred Games" is profoundly influenced by the big, fat British novels of the 1800s -- "Our Mutual Friend," "Vanity Fair," etc. -- and if almost none of it is set in London itself, the big, dirty, maddening, glorious city of Mumbai makes a worthy successor. When the people in "Sacred Games" feel tired of Mumbai, they are tired of life, and vice versa. They get run down, disgusted, harried, misanthropic or old, but no sooner do they hightail it out of the city, than they find themselves jonesing for it again, longing for the perpetual noise and what one character calls "that particular Bombay stink in the thick air, of petrol fumes and pollution and swamp water." As with life, the only way to get Mumbai out of your system is by dying.

The popular novels of the Victorian era hung on tales of inheritance and marriage; the popular fiction of our day hangs on crime. And so "Sacred Games" is a cops and robbers tale, albeit a vast and exquisitely constructed one. The cop is Sartaj Singh, a tall, handsome, thoughtful Sikh police inspector who has never been conniving enough to muscle his way to the top of the force, and the robber (and killer and smuggler) is Ganesh Gaitonde, a celebrated Mumbai gangster, the Indian equivalent of a Mafia don. At the beginning of the novel, Sartaj follows an anonymous tip to an odd, cube-shaped house on the edge of town, where he discovers Gaitonde holed up in what appears to be a near-impenetrable fortress.

The showdown ends in bulldozers, bullets and death, but somehow, even though the bad guy's been killed, the real mystery has only begun to emerge. Muckety-mucks in India's national intelligence agency want to know what Gaitonde was doing in this strange house, and who the dead woman found beside him could be. Sartaj's boss and mentor, a superb political gamesman, assigns him the task of solving these puzzles. Into the story of his investigation comes barging the first-person voice of Gaitonde himself, who in alternating chapters tells us how he remade himself from a young, no-account hired thug into one of the two biggest godfathers in the country (the other being Suleiman Isa, a Muslim and Gaitonde's great rival). Meanwhile, Sartaj slowly gets to the bottom of a plot that menaces no less than the future of Mumbai itself.

"Sacred Games" offers as much murder, ruthlessness, malfeasance, scheming and profanity as an average season of "The Sopranos" -- though you'll only be able to appreciate the abundance of the profanity if you take advantage of the glossary at the back of the book. I didn't even realize the glossary was there until I finished, but by then I'd figured out that "randi" means "whore," "gaand" means "ass" and "maderchod" surely referred to someone who engages in erotic relations with his own mother. I kind of enjoyed figuring all this out by context, but my favorite specimen of Indian slang needed no translation. "It's too filmi," characters in "Sacred Games" often say, meaning that some situation or suggestion or even film too much resembles the glossy, overblown melodramas in the Bollywood movies they all watch obsessively.

"Sacred Games," though often suspenseful, is never filmi. Although the meat of this novel clings to the bones of a crime story, and there's certainly plenty of crime in it, the book is really a passionate tribute to contemporary India in all its vigor and vulgarity. Because it's not a family saga, it blessedly avoids what have become the clichés of the Indian literary novel; you will find no moldering colonial mansion here, with a couple of colorful, bickering, scolding aunties rattling around inside, and no brainy, ambitious young lad who becomes enamored of British culture to the point of losing his own. Chandra's characters are thoroughly modern, and Mumbai is the center of the universe as far as they're concerned. Some minor players, whose stories are robustly sketched in interludes Chandra calls "insets," broaden the canvas further; they include a double agent working with Islamist militants in London, a teenage girl in suburban Virginia and, most riveting, a farm boy turned scholar turned Marxist guerrilla turned small-time gang leader.

The two men who pull this far-flung ensemble together, Sartaj and Gaitonde, appear to be opposites. One is a lawman, the other an outlaw, but more important, one is the awesome force of human ambition untrammeled by conscience or fear, while the other is a modest man with a "loyalty to the ordinary," who only wants to do his job as well as he can and keep his head down. One has a spectacular movie star for a mistress and virgins shipped in from all over Asia for his delectation; the other has hardly touched a woman since his wife divorced him. But Gaitonde sees a kinship between them all the same (the parts of the novel narrated by him are directed at Sartaj). By the end of the book that kinship comes into focus as the threat to Mumbai grows ever closer, giving "Sacred Games" a satisfying completeness that's all too rare among today's baggy, doorstop novels.

The biggest threat to Chandra's Mumbai might seem to be religious friction (the characters are Hindu, Muslim, Sikh and Christian) in a nation whose commitment to secular democracy has wobbled under many sectarian blows. Sartaj's mother lost her beloved sister in the Hindu-Muslim riots during the Partition of India and Pakistan in the 1940s, and Mumbai itself was reconfigured by the unrest following the destruction of the Babri Mosque in the early 1990s, both depicted in "Sacred Games." But Chandra takes an even longer view; to him the battle is literally between life and death, between those who understand that this world is necessarily chaotic, flawed and painful and those whose craving for order, calm and purity make them so very, very dangerous. Finally, the choice is not between believer and infidel, or even between good and evil, but between Mumbai and the grave.

Shares