Like virtually all works of historical writing, Amy Chua's "Day of Empire" has more to do with the present than the past, and more to do with the writer's own society than with its purported objects of study, which range from the Persian Empire to the Tang Dynasty of imperial China and the 17th century Dutch Republic.

Chua is a professor at Yale Law School whose 2002 bestseller, "World on Fire," offered compelling evidence of the devastation inflicted on the developing world in the name of economic globalization. In particular, Chua effectively demolished the myth that so-called free markets breed democracy and progressive social change. "Day of Empire" derives from a similar impulse to resist widespread and potentially dominant dogmas of the day -- in this case, not the dogmas of neoliberal economists but those of neoconservative foreign-policy wizards and their allies.

You certainly can't complain that Chua's book lacks breadth or ambition. In fewer than 350 pages, she tries to survey the history of imperial "hyperpowers" -- beginning with Cyrus the Great of Persia in 550 B.C. and passing through Rome, China, the Mongol Empire, medieval Spain, Holland, the British Empire and Nazi Germany, with a few other stops on the road to post-9/11 America.

Meanwhile, like some knight errant in a legendary romance, she must fight off not one but two fearsome monsters along the way. On one flank, Chua struggles to spear the clanking pseudo-pragmatist argument put forward by historian Niall Ferguson and neocon think-tanker Max Boot, among others -- and all but explicitly adopted by the Bush administration -- that the United States must embrace its imperial mission and civilize the globe, by force if necessary. On the other, she seeks to banish the hollow-eyed specter of a paranoid, xenophobic society, seeking to protect its "national identity" and core "Anglo-Protestant" values, in the words of Samuel Huntington, with border fences, immigration crackdowns and English-only laws.

One of the central points in "Day of Empire" is that the positions thus represented, while they may sometimes be held by the same people, are not compatible. If Chua's reading of history is correct, imperial powers have universally thrived by accepting and accommodating cultural diversity, at least in relative terms. On the other hand, when imperial societies have turned inward, closed themselves off from the outside world and retreated into ethnic or cultural chauvinism, the end was generally in sight. Indeed, she finds in history near-inevitable progress from monster A to monster B: Nations rise to global hegemony by being extraordinarily pluralistic and tolerant, but such imperial expansion eventually reaches a tipping point, triggering internal conflict and xenophobia, which leads to imperial decline.

Chua clearly wants to argue that the United States should put down the white man's burden, abandon any imperial ambitions and back gradually away from its anguished, perched-on-the-precipice position as the world's sole hyperpower (which admittedly hasn't gone so well lately). Being a "mere superpower" in a multipolar century, potentially counterbalanced by the European Union, Russia and China, she suggests, may be a better prescription for longevity. Of course, she also wants to argue against nativism, isolationism and chauvinism, and draws appealingly on her own experiences as the American-born daughter of Filipino-Chinese immigrants.

Like much of Chua's down-with-Bush, out-of-Iraq audience, I'm inclined to agree with both of these positions. That doesn't make them necessarily connected; it's perfectly possible to hold one view without the other. Niall Ferguson, Christopher Hitchens and Thomas Friedman, for example, might all share the "liberal" notion that America's global predominance is intimately linked to our ever-shifting national tapestry of ethnicity, race and religion -- and that to embrace the first you must embrace the second. Pat Buchanan and Ron Paul, on the other hand, would like to retreat from hegemony, bring our troops home from Iraq (and anywhere else they happen to be at the moment) and let the Middle East sort out its own problems -- while expelling illegal immigrants and slamming down an iron curtain along the Mexican border.

As Democratic presidential candidates are reportedly, and uncomfortably, discovering on the campaign trail, anti-immigrant fervor is not restricted to the right wing. It may be an irrational response to economic anxiety, but it is real, persistent and evidently immune to arguments about the price of restaurant meals or supermarket lettuce. (Paul remains the longest of long shots as a Republican candidate, but he's pretty much the only contender in either party who's telling Middle American voters exactly what they want to hear on both immigration and Iraq.)

In this context -- a nation waging a failing and cripplingly expensive overseas war while internally destabilized by acrimonious debate -- Chua's appeal to an alternate vision of the U.S. as "a hyperpower of opportunity, dynamism and moral force" seems like a wistful glance into the rear-view mirror rather than a look at the road ahead.

"Day of Empire" is a lively read, full of intriguing factoids and persuasive rhetoric, and the potential applicability of its case histories to America's current quandary, at least, is clear enough. Chua works hard not to oversimplify her encapsulated imperial histories, making clear, for instance, that the "tolerance" and "diversity" of the Achaemenid Persian Empire were instrumental methods of subjugating and absorbing conquered peoples, a long way from any modern conceptions of human rights or international law. Still, under Cyrus and his successor Darius the Great, the Achaemenid court became the most cosmopolitan place the world had yet seen, bringing together "Egyptian doctors, Greek scientists and Babylonian astronomers." (At its peak, Darius' realm extended as far east as India and as far west as the Danube River.) Local laws, customs and religions were widely tolerated -- most famously, Cyrus freed the Jews from their Babylonian captivity and rebuilt the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem at his own expense -- just as long as taxes and tribute kept flowing.

Apparently the empire's "official" languages included Aramaic, Elamite, Babylonian, Egyptian, Greek, Lydian and Lycian (take that, English-only campaigners!), although Darius probably couldn't read any of them. Like most subsequent empires, Chua contends, the Achaemenid dynasty came unstuck for the simplest of reasons: It lacked adequate social and political "glue." "No common religion, language or culture bound the sprawling empire together," she writes; the Persians offered no conception of imperial identity or citizenship to conquered peoples, who were assumed to be innately inferior. Greeks, Egyptians and Phoenicians went right on being Greeks, Egyptians and Phoenicians under tolerant Persian rule, and when Darius' son Xerxes and his successors apparently turned cruel and intolerant -- demolishing Egyptian cities and despoiling Athenian shrines, according to some reports -- "the distinct peoples ... eventually turned on the empire itself."

In many ways, the Persian Empire is the cleanest and clearest instance of Chua's repeated historical narrative -- an empire is built on widespread tolerance, then crumbles when imperial glue melts under the heat of internal conflict -- which makes me a little suspicious, since it's also the case furthest away in history and the one about which scholars know the least. She dispenses with the Roman Empire in 29 pages and the British Empire in 38, making essentially the same points about both: New and highly effective ideas about glue were pioneered, whether this meant the Roman notion of widespread male citizenship or the British idea of empowering an English-speaking and English-educated elite; but in the long haul their dominions were torn apart by ethnic or religious bigotry and infighting.

Chua isn't a historian, and spends too much time apologizing for that fact. But she does have a keen eye for the telling detail in these truncated, scattershot accounts. If the Romans viewed nearly all foreigners as barbarians in need of civilizing, there is no evidence that they viewed skin color -- what we would today call race -- as important in any way. (Why would they? The light-skinned people they encountered in northern Europe were probably more primitive, on the whole, than the dark-skinned people they met in southern countries.) At least one emperor, Septimius Severus, was born in North Africa, and the son of a Berber tribesman from modern-day Algeria grew up to become Quintius Lollius Urbicus, governor of Britain and finally city prefect of Rome.

She also notes that the English-Scottish union of 1707 helped launch the British Empire's global reach, by enabling the Crown to divert the formidable entrepreneurial, intellectual and warlike energies of the impoverished people on England's northern frontier to new projects all over the world. And Chua is absolutely right that Britain's failure to successfully absorb another neighboring people (the Irish) presaged the "racial and ethnic arrogance" that fatally undermined British rule in India, proverbial jewel in the imperial crown. In what I'm afraid is probably a typical overcondensation, however, she boils the Anglo-Irish relationship down to a single issue (religious bigotry), when the truth -- if there's any truth to be found in 800 tormented and incestuous years of history -- is quite a bit more complicated.

I was excited to read Chua's bite-size accounts of other imperial civilizations about which I know next to nothing. She acerbically discusses the Tang Dynasty, which presided over the most prosperous, powerful and accomplished age of the world's most xenophobic major nation -- and was founded in the 7th century by Taizong, a northern warlord of mixed Chinese and Turkish ancestry. Once the religious and ethnic tolerance epitomized by Taizong and the later Ming Huang were abandoned in subsequent centuries, Chua argues, imperial China slipped into a long, slow, inward-looking decline that left it culturally and technologically far behind the West.

She's also fascinating on the subject of Genghis Khan and the Mongols, the "cosmopolitan barbarians" who thrived on adopting the best elements of every culture they came across, and who, despite lacking any science, engineering, agriculture or written language of their own, conquered Baghdad, Belgrade, Moscow and Damascus. For that matter, Chua does a nice job of summarizing the story of the Dutch Republic, which became a commercial (but never military) superpower almost overnight by welcoming Jews and Protestants who had been driven out of many other European countries by religious persecution -- along with their money.

But how far do you have to twist the definition before the Netherlands, a tiny European country that as late as 1579 was ruled directly by the Spanish crown, becomes an imperial "hyperpower"? Without question, the 17th century Dutch Republic played an enormous role in spreading capitalism to every available corner of the globe. It was probably the richest nation in the world -- shopkeepers were said to clothe their wives in silk, satin and jewels -- and because of that also the best educated and the most liberal. Women had extraordinary freedom. Clerical strictures on vice and pleasure were widely ignored. Amsterdam became a center of artistic and intellectual life; if Rembrandt and Vermeer were Dutch by birth, Descartes, Spinoza and John Locke all settled there.

One could add that Holland enjoyed all this prosperity precisely because it perfected the art of buying and selling, and never tried to conquer the world militarily. Indeed, the principal Dutch military venture of this period brought an end to whatever superpower status it briefly held. In 1688, the Dutch nobleman William of Orange invaded England and usurped the British throne from King James II, who was both his uncle and his father-in-law. By transplanting the Dutch navy, its Sephardic Jewish financiers and a talent pool of skilled workers to London -- along with, as Chua puts it, the Dutch "business model" of welcoming immigrants and religious minorities -- William laid the foundation for the rise of a genuine hyperpower.

What's wrong with "Day of Empire" isn't so much that Chua gets the details wrong sometimes, makes dubious arguments or oversimplifies her case studies, although I bet that happens more times than I've been able to identify. It's something more ambiguous, something harder to pin down. It seems to me that her ideas about history -- what it is, what it does and the kinds of lessons it can offer us -- are themselves a little simplistic.

In her introduction, she discusses the potential risks of "selection bias," the tendency in social science to choose only examples that support one's existing thesis, but her entire book is about selecting data points from wildly different times and places and cramming them into a one-size-fits-all interpretation. It isn't that she's wrong in observing that the Achaemenids, Romans, Tang Chinese and British built long-lasting empires by accommodating diversity in various ways and to various degrees, while the opposite approach (viz., Nazi Germany and the Holocaust) has proven strikingly unsuccessful. But that observation doesn't tell you anything except that empires, like polar bears and elephants, tend to be large and dangerous things.

Any graduate of a third-rate business school can draw up a PowerPoint display to convince you that organizations will be judged on how they manage complexity. On the other side of Chua's coin, anybody who wasn't stoned during high-school physics can tell you that all systems of energy eventually decay into entropy. It's only half facetious to say that she assembles a miscellaneous mass of more or less intriguing evidence to support those two ideas, on the way toward a brief and interesting chapter that sways from optimism to fatalism and back again while discussing the U.S. and its current dilemma.

As Chua reluctantly admits, the examples of high imperial history -- the Romans, the British, the Tang -- have little to do with the present case. Pluralistic to its core yet perennially plagued by nativist hatred, the United States has become a combination of the Achaemenid Empire, which ruled by military force but made no effort to "Persianize" its subjects, and the Dutch Republic, which employed internal policies of immigration and toleration to build a commercial powerhouse that bought chocolate low and sold it high. Presumably, the U.S. could defeat any other nation in open military conflict -- something America's opponents are now savvy enough to avoid -- and despite mounting national debt and a massive trade imbalance, it remains the world's largest economic power.

Unlike the Roman and British empires, the American imperium so ardently desired by Ferguson, Boot and others has little to offer the rest of the world beyond a cultural and ideological bill of goods that is viewed with increasing suspicion. It's a new kind of empire facing an old problem: not enough glue. Pax-Americana advocates may be eager to invade all kinds of vastly smaller nations, but the last thing they want is to extend U.S. citizenship to Iraqis or Iranians or North Koreans or Venezuelans. Inviting the best students from those countries here to study might have been acceptable in the flush years after World War II, but something tells me that wouldn't go over big right now.

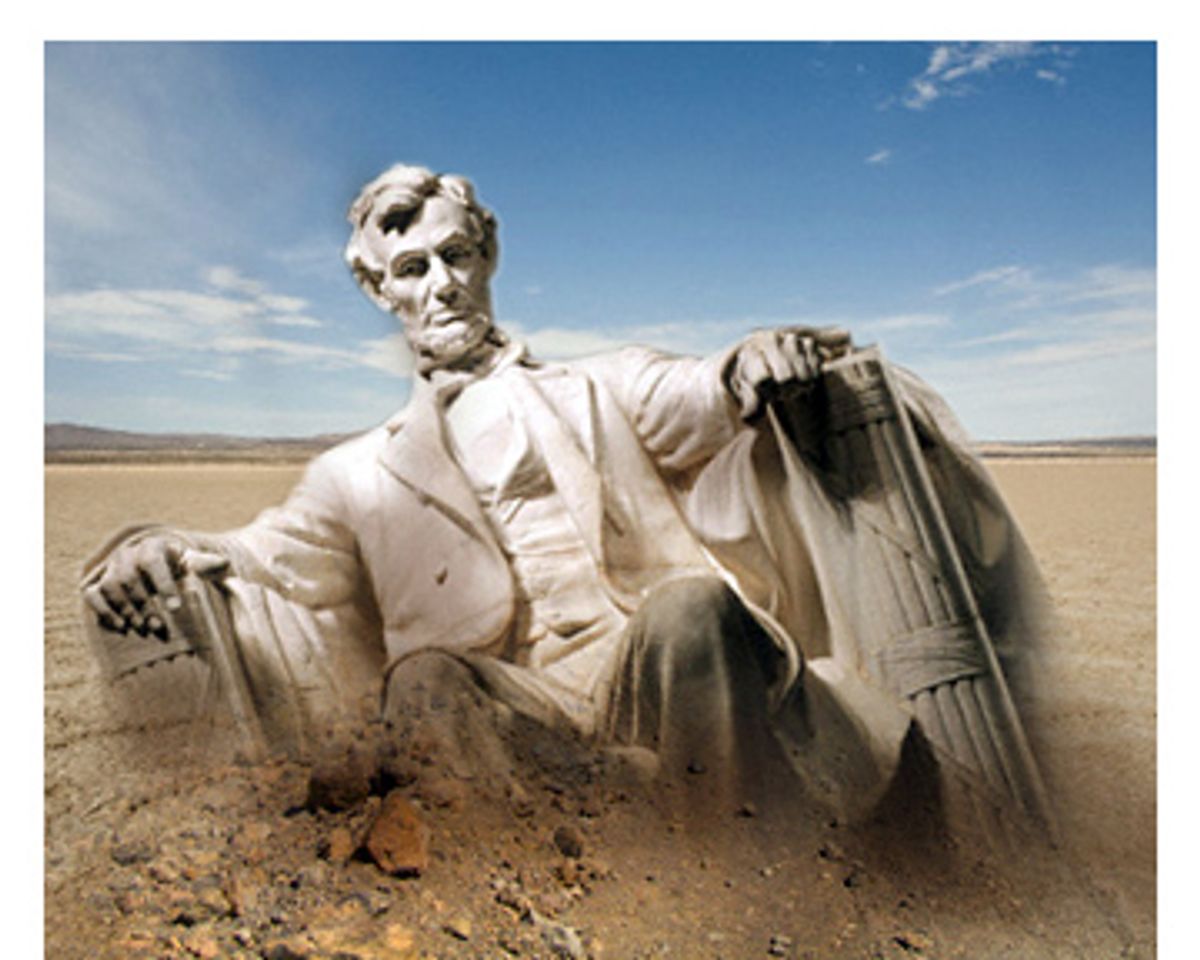

Instead, our decrepit colossus lumbers around the world feeling unloved, bearing freedom's cup in one hand and an M16 rifle in the other. But the cup is made of plastic and came free with a BK Double. The American promise of a blend of democracy and capitalism that could make the whole world America-like is hardly taken seriously by anyone anymore, and it's only Americans, cosseted by a soft 'n' squishy mountain of consumer debt and buffeted by wall-to-wall media coverage of Britney's latest indiscretion, who don't know it.

Do we seriously believe the world hasn't noticed that American democracy has been eaten out from within, like a cotton boll infested with weevils, and that American consumer capitalism, cruel as it can be, bears almost no resemblance to the "free markets" inflicted on the developing world? After surveying the global wave of anti-Americanism that flowed from the invasion and occupation of Iraq, and the xenophobic post-9/11 backlash within the U.S., Chua concludes that transforming the country into "an aggressively militaristic hyperpower" would be massively costly both in human and financial terms, "without any of the benefits that accrued to empires of the past."

That's a fine conclusion as far as it goes. Chua's mistake, I believe, is to assume -- naively, after all the reading she's done -- that political leaders in 21st century America still possess the will, the ability or even the power to stop the inexorable process of imperial decay.

Shares