Early last year, John McCain seemed to lash his political fortune to the success or failure of the troop "surge" in Iraq. Backing the surge fit his carefully tended reputation as a maverick; his allies noted that McCain was bravely risking his political career to do what he believed was right. "I have just finished an election campaign," Sen. Joe Lieberman said last January when he and McCain pushed the surge at a meeting at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. "If rumors are correct, he may be starting one," Lieberman said of McCain, standing at his side. "He is not taking the easy way out here. But he is taking the way that he believes is best for the safety of our children and grandchildren and the values and the way of life that America has come to represent."

A year later, leaving aside the question of its long-term effects, the surge has had a tangible short-term security impact in Baghdad. And McCain, in his campaign for the Republican presidential nomination, isn't going to let us forget that he knew better all along. "I'm proud to have been one of those who played a key role in bringing about one of the most important changes in recent years," McCain trumpeted during the GOP debate in Manchester, N.H., on Jan. 6. "And that was the change in strategy from a failing strategy in Iraq pursued by Secretary Rumsfeld." Two days later, McCain won the Granite State primary.

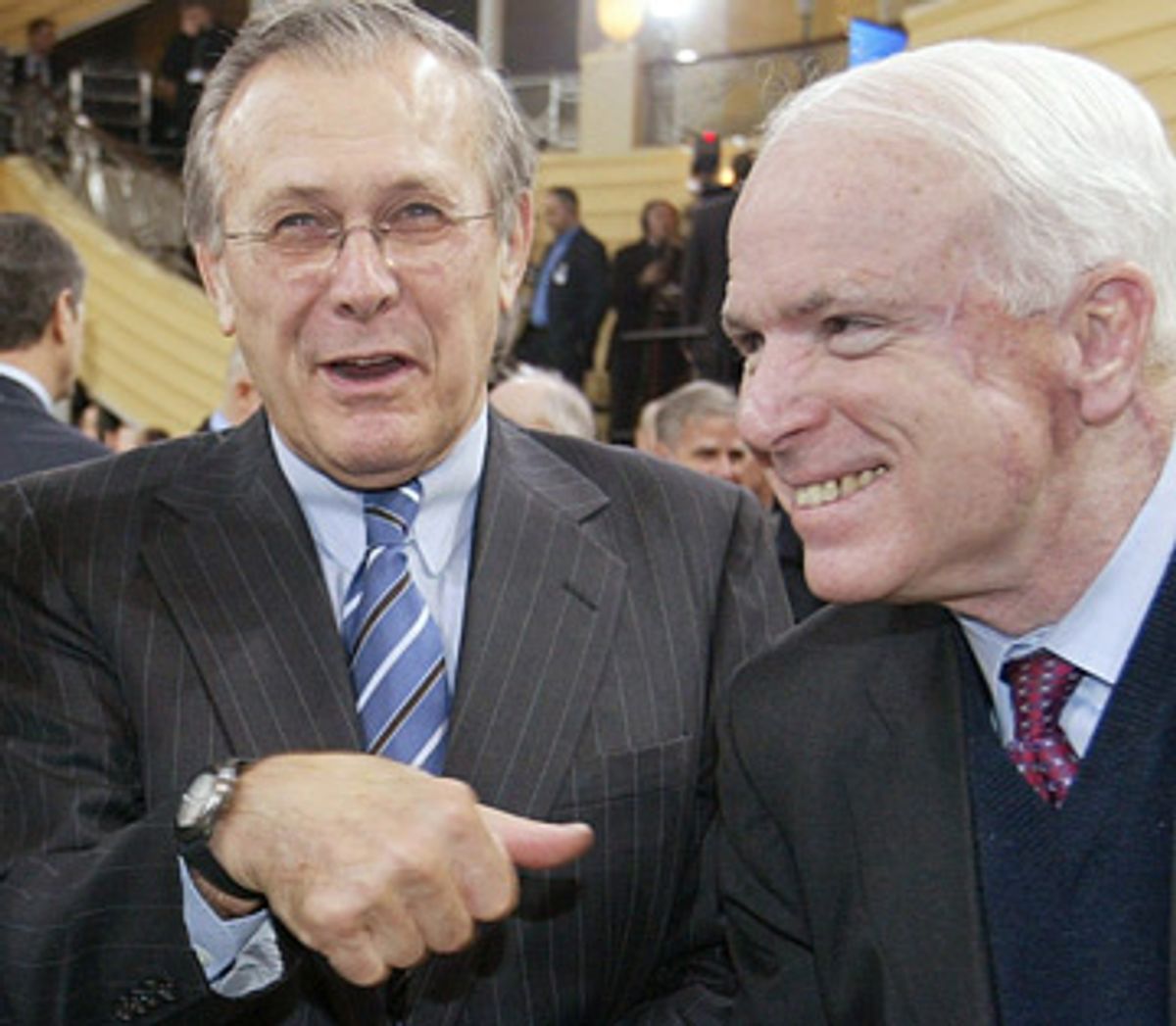

In fact, lately former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld has become quite the punching bag for McCain on the campaign trail. Part of the McCain mantra, whether recited on the stump or to reporters on his campaign bus, is that he knew that Gen. David Petraeus' surge of troops would work better than Rumsfeld's light footprint approach. It's his way of supporting the war while criticizing the way it was executed by the Bush administration without ever uttering the word "Bush." It is also meant to be proof of the gravitas McCain would bring to the job of commander in chief. "I have the knowledge and experience and judgment, as my support of the Petraeus strategy indicated, and my condemnation of the previous Rumsfeld strategy," said McCain in a Jan. 9 NBC "Today" show interview. "No other candidate running for president did that on either side."

But to buy into the McCain-knows-best version of the Iraq war, you have to ignore a lot of history. McCain was among the most aggressive proponents of a preemptive strike against Saddam Hussein, cosponsoring the resolution authorizing the use of force against Iraq. He also expressed full faith in the way it would be executed -- a war plan conceived and executed by Rumsfeld.

He did call for more troops in Iraq sooner than some, but later than others who made the same argument before the first shots were even fired. And McCain's support for Rumsfeld only evaporated over time, as it became painfully clear that the war in Iraq was going south.

Bert Rockman, the head of the political science department at Purdue University, said McCain's commander-in-chief argument is tarnished because he advocated "the right tactics and the wrong strategy."

"It was a mistake probably to have gone in, that is the real issue," Rockman explained. "We have discovered there are worse things than Saddam Hussein."

During the run-up to the war, McCain argued vociferously in favor of an invasion, quoting the logic of Vice President Dick Cheney. "As Vice President Cheney has said of those who argue that containment and deterrence are working, the argument comes down to this: Yes, Saddam is as dangerous as we say he is," McCain said in a saber-rattling speech at the Center for Strategic and International Studies on Feb. 13, 2003. "We just need to let him get stronger before we do anything about it," he added sarcastically.

In the period leading up to the war, McCain sounded, at times, less like a straight-talking maverick and more like the neoconservative former Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz. "It's going to send the message throughout the Middle East that democracy can take hold in the Middle East," McCain said about the war on Fox's "Hannity & Colmes" on Feb. 21, 2003. He seemed to think Iraq would be a cakewalk, predicting that the war "will be brief."

He also sounded like Wolfowitz's boss, Donald Rumsfeld, as far back as late 2002. Despite all his talk now about more troops, as the war drums built toward a crescendo, McCain argued that better technology meant fewer troops were going to be needed in Iraq. "Our technology, particularly air-to-ground technology, is vastly improved," McCain told CNN's Larry King on Dec. 9, 2002. "I don't think you're going to have to see the scale of numbers of troops that we saw, nor the length of the buildup, obviously, that we had back in 1991." It was pure Rumsfeld.

But even back then, not everyone was so sure that the war would be brief or that Rumsfeld's smaller force would be sufficient. On Feb. 25, 2003, then-Army Chief of Staff Gen. Eric Shinseki famously warned the Senate Armed Services Committee that "several hundred thousand" soldiers would be needed to take and hold Iraq. Rumsfeld publicly disagreed with Shinseki's estimate.

If McCain shared Shinseki's position, he didn't say so at the time. "I have no qualms about our strategic plans," he told the Hartford Courant in a March 5 article, just before the invasion. "I thought we were very successful in Afghanistan."

And while he was quiet about Shinseki, McCain shouted down some naysayers who proved to be much more prescient than he. On the cusp of the invasion, West Virginia Democrat Sen. Robert Byrd took to the Senate floor on March 19, 2003, to denounce the war. It was a speech that predicted the future debacle so accurately that it now seems that the senior senator from West Virginia had a crystal ball in his Senate desk. "We proclaim a new doctrine of preemption which is understood by few and feared by many," Byrd warned. "After the war has ended, the United States will have to rebuild much more than the country of Iraq. We will have to rebuild America's image around the globe."

McCain pounced, taking to the Senate floor to predict that "when the people of Iraq are liberated, we will again have written another chapter in the glorious history of the United States of America."

By June 2003, McCain was still generally in the "Mission Accomplished" camp. "I have said a long time that reconstruction of Iraq would be a long, long, difficult process," he told Fox News on June 11. "But the conflict, the major conflict is over ... The regime change is accomplished."

It was during an August 2003 visit to Iraq that McCain seems to have realized that the Iraq tale was not unfolding as another chapter in the glorious history of the United States. (It is not entirely clear when he came to the realization, since the McCain campaign failed to return my call asking for a staffer to go through this history with me.) While he was in Iraq, insurgents used a truck bomb to blow up the United Nations headquarters in Baghdad on Aug. 19, killing U.N. envoy Sergio Vieira de Mello. McCain told NPR on Aug. 29, 2003, that "we need more troops" in Iraq. "When I say more troops, we need a lot more of certain skills, such as civil affairs capability, military police. We need more linguists," McCain added.

And McCain was not always sour on Rumsfeld. As late as May 12, 2004, in the wake of the Abu Ghraib scandal, McCain was asked on "Hannity & Colmes" whether Rumsfeld could still be effective in his job. "Yes, today I do and I believe he's done a fine job," McCain responded. "He's an honorable man."

It is true that by late 2004, McCain was down on the secretary of defense, telling the press that he had "no confidence" in Rumsfeld. But the clips show that he stopped short of calling for Rumsfeld's resignation, saying it was the president's prerogative to pick his own national security team.

To be fair, McCain has been calling for more troops for years now. And political experts do think McCain's argument on the surge may still gain some traction among GOP voters. "We still have about two-thirds of Republicans who support the effort in Iraq," explained Stephen Wayne, a professor of government at Georgetown. "It certainly would work with the Republican audience he is appealing to." That may depend, in part, on the memories of the people in that audience.

Amanda Silverman contributed reporting to this article.

Shares