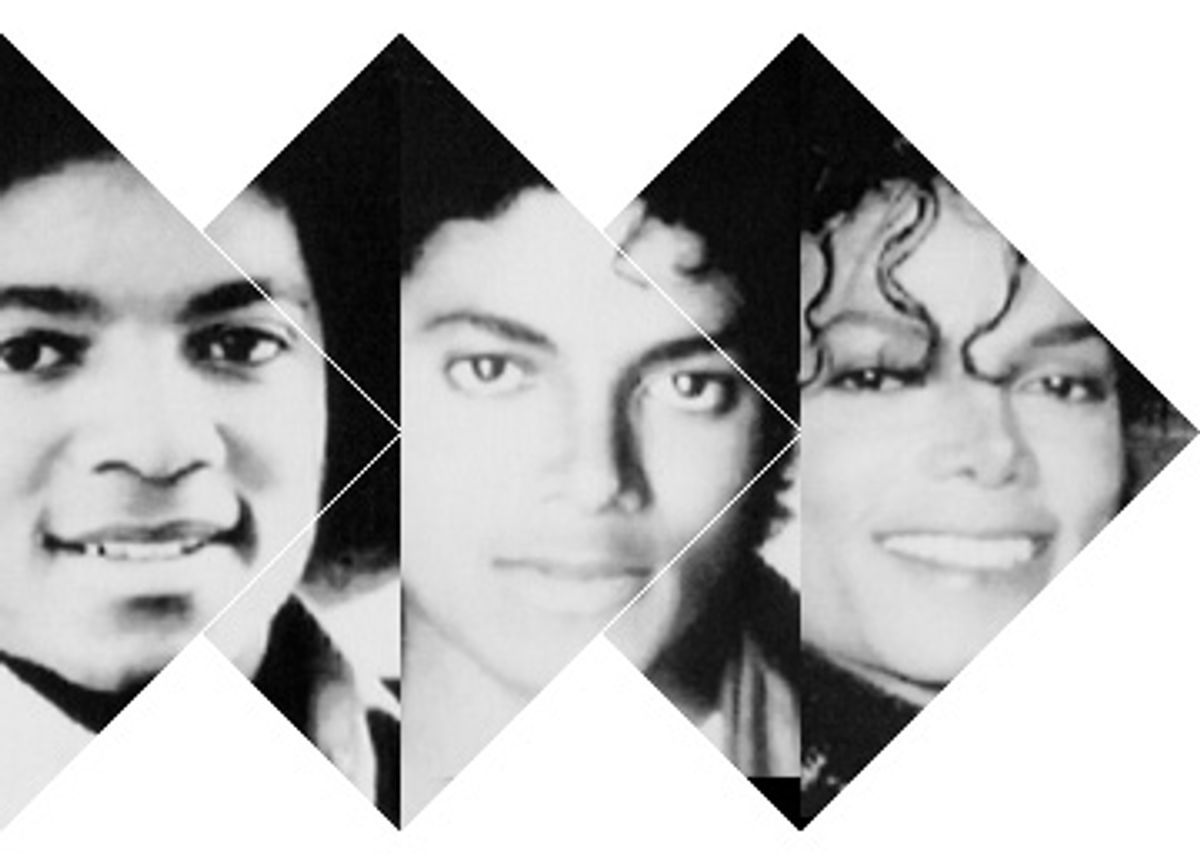

Anybody so inclined can see the psychological demons behind Michael Jackson's facial work-in-progress. In contemporary psychiatric jargon, such morbid obsession with one's looks is called body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), from "dysmorph," the Greek word for misshapen. Though few are as alarming as Jackson, we all know folks who are preoccupied with the shape of their nose, the cleft of their chin or the size of their breasts, and are constantly seeking the latest cosmetic fix, be it surgery, Botox, collagen, fat injections or various implants. Estimates of the incidence of BDD vary widely; there is no yardstick for when body image concerns should be considered excessive and presumably pathological. A good guess is that BDD occurs in about 1 to 2 percent of the general population, but in as much as 7 to 30 percent among those seeking repeated cosmetic surgery.

Such patients are easy to mock; some less than sympathetic journalists have dubbed BDD the "imagined ugliness syndrome." However, to the sufferers, every bodily deviation from perceived perfection is both real and profoundly disturbing. Many become socially isolated, have difficulty holding jobs and suffer from serious depression. In a prospective study, over 50 percent of patients with BDD admitted to thoughts of suicide, with an attempted suicide rate of 2 to 3 percent per year, and an overall suicide rate of greater than 20 percent.

Because BDD is a serious disorder with potentially tragic consequences, a better understanding of its root causes would be a welcome medical advance. But how are we to think about a condition that is associated with widely disparate personality types and seems so driven by cultural pressures? Unlike mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, where biology clearly plays a major role, it's hard to see how excessive concern with the shape of one's nose or lips arises from brain mechanisms gone askew.

Now medical researchers believe they have found a biological cause. In December, a team of UCLA psychiatrists conducted an fMRI study of BDD patients. Their results suggest that BDD patients may suffer from faulty visual processing, causing them to have skewed images of themselves and others. While it's an intriguing study and could provide some insights into BDD, it is ultimately inconclusive and underscores the fallacy of basing behavior on fMRI brain scans.

At UCLA's obsessive-compulsive-disorder treatment program, James Feusner and colleagues asked 12 patients with BDD and 13 normal control patients to examine a series of photographs of unfamiliar faces, while undergoing fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) scans. Each face was shown in three versions: an unaltered photo, a blurry image that eliminated detail and a photo that exaggerated facial outlines. Previous fMRI research has suggested that each category -- -- normal, blurry or exaggerated -- is processed by separate neural pathways. When the image was normal or blurry, control subjects used neural pathways involved in analyzing the face as a whole; only when presented with exaggerated facial features did the control patients activate neural pathways known to focus on details. However, the BDD group viewed all three categories via the neural pathways that zero in on details, while not engaging those pathways that evaluate the face as a single unit.

Feusner's interpretation is that BDD patients' "brain hardware is fine, but there's a glitch in the operating software that prevents patients from seeing themselves as others do ... There is an abnormality in how BDD patients' brains interpret what they see." Though not offering an explanation of why "their brains are programmed to extract details -- or fill them in where they don't exist," Feusner says that "BDD has a biological link and can no longer be attributed solely to our society's focus on appearance." He adds that in the future, patients' brains might be retrained to perceive faces more accurately.

The study has been widely reported as being the first demonstration of "a biological reason for BDD patients' distorted body image." Newsweek opined, "Doctors and patients can only hope that such tangible evidence of pathology will help remove the stigma attached to most mental illnesses."

But can an fMRI determine a "glitch in the brain software" or that a mental condition is the reflection of an underlying brain abnormality? Can it make the arbitrary determination of whether a behavioral disorder has a primary psychological or biological basis? To approach these questions, let me briefly present a classic study of brain development that offers a basic insight into the "biology" of "hard-wiring." Though I've chosen a simple rat study, the underlying principle of neural organization applies equally to humans.

The rat's auditory cortex -- the part of the brain that processes incoming sounds -- continues to develop for about two weeks after birth. After that, the circuitry becomes relatively fixed. This two-week postnatal window of brain plasticity allows researchers to study how changes in experience during that time might affect what will be seen as "hard-wired" neural circuitry.

The auditory cortex of rats (and humans) is subdivided so that neurons in different regions preferentially respond to a relatively narrow bandwidth of sound. For example, some cells respond to high-pitched sounds but not low-pitched ones, while others respond to low-pitched sounds but not high-pitched ones. By exposing adult rats to different-frequency sounds while recording electrical activity from individual cortical neurons, researchers have been able to create topographic maps of which regions of the normal rat auditory cortex respond to which frequencies.

But the circuitry of the adult auditory cortex depends upon what the rat hears during the critical two-week postnatal period. If rats are exposed to a full range of ambient sound, the adult cortex will have a normal sound frequency distribution. If during the first two weeks of life, rats are exposed to only a single sound frequency, the adult rats will have many more neurons and a greater cortical area devoted to this frequency, and far fewer neurons and a diminished cortical representation for other frequencies. In short, the developing brain uses environmental cues to determine its final structure.

Now, to get a sense of the problem in attributing causation to fMRI findings, pretend that you are a neuroscientist who has just received your latest shipment of lab rats. They arrive without any accompanying papers documenting involvement in any prior experiments. One, Helen, seems different from the others; she never responds to her dinner bell. Being curious, you slip poor Helen into the fMRI scanner. To your surprise, you discover that high-pitched sounds produce very little cortical activation in her, when compared with her cage mates.

It would be logical to conclude that Helen's decreased auditory cortex activation correlates with her inability to hear high frequencies. You would be justified in issuing the not-very-meaningful observation that there is a biological link between Helen's defective hearing and the structural anatomy of her auditory cortex. But here's where modern neuroscience needs to have a healthy dose of self-restraint: You can describe correlations; you cannot ascribe causation.

Without Helen's pediatric history -- knowing what sound frequencies she was exposed to as a baby rat -- you could not know that her adult fMRI findings represented a normal response to an abnormal auditory environment during a crucial phase of brain development. You wouldn't be justified in using the fMRI findings to postulate a possible underlying brain disorder, disease or software glitch. FMRI measures brain activity at any given instant. It does not tell us why this activity is occurring; it cannot tell us about the root causes of behavior.

I suspect that the UCLA study is documenting the human equivalent of Helen. Rather than offering an insight into a possible biological cause of BDD, the UCLA study may be a more sophisticated way of showing what we already know -- that childhood events can physically shape the developing brain into a different way of seeing the world.

Though some degree of brain plasticity persists throughout life, the earliest years, when the brain is under development, are the most crucial. It is easy to see how a young child -- criticized by parents or schoolmates for ears that stick out too far, or a nose that is too big or too long -- might begin comparing herself with the gold standards offered up by TV, movies and magazines. Each new image is yet another opportunity for self-evaluation. This process invites a feature-by-feature comparison, and what originated as a purely psychological state -- dissatisfaction with one's appearance -- gradually is converted into a biological tendency to see facial details rather than the entire face.

The UCLA study also underscores the difficulty of distinguishing between "emotional" and "biological" causes of a mental disorder. With BDD, it is easy to argue that a child may have a genetic predisposition to obsessions -- seen in families with obsessive-compulsive disorder -- and so might be more inclined to ruminate over each perceived facial feature flaw. But against this genetic backdrop, keep in mind that Helen was a completely normal rat whose abnormal brain function was exclusively the result of environmental deprivation.

Even conventional language contributes to the confusion of emotional vs. biological. If a person believes that a perfectly normal-shaped nose is too wide and ugly, and his fMRI is different from those of a control group, is his problem now "real" as opposed to "all in his mind"? All beliefs, no matter how bizarre or ill-founded, will be manifest as physical brain changes. Demonstrating these changes says nothing about the realness of the belief, nor does it document the presence of a tangible pathology.

Even with these caveats, the UCLA fMRI study may be giving us a very different insight into the evolution of BDD. Ride a subway and watch a 10-year-old girl reading a teen fashion magazine, her index finger intently tracing the outline of a waif-thin model's collagen-fattened lips, and then, with a sullen sense of defeat, examine her own reflection in the subway window. I can't know with certainty, but I suspect that the UCLA study is documenting the power of our culture of appearance to shape our ability to see ourselves and others, even to the extent of creating or at least facilitating a psychiatric disorder of monumental consequences.

Since the beginning of time, parents have worried about kids' role models. Can bad ones be destructive? Neuroscience is saying yes. So perhaps it's time to see our obsession with "perfect" features as being as toxic as secondhand smoke or exposure to pesticides, as likely to cause mental problems as war is to cause post-traumatic stress disorder in soldiers. Kids deserve better. They need to learn from parents and authority figures that self-esteem isn't dependent upon a cookie-cutter imitation of the celebrity du jour. The best medicine is preventive medicine. And the best single preventive for BDD is the simple lesson that beauty comes in all sizes, shapes and personalities.

Shares