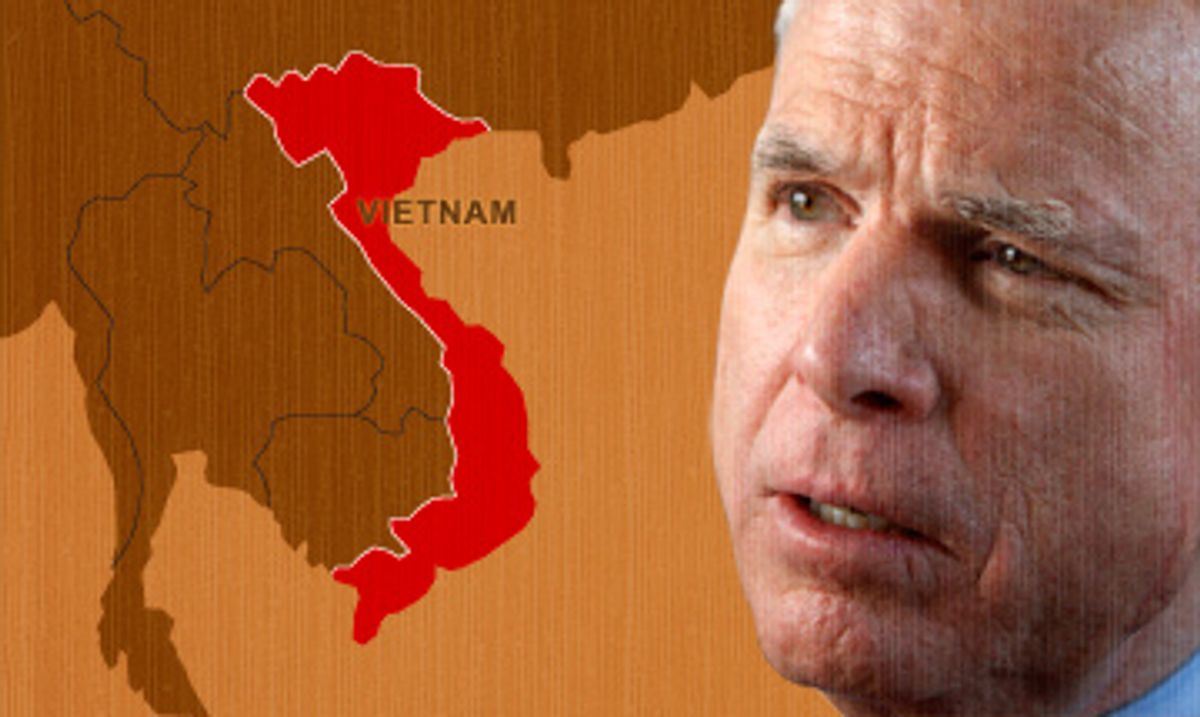

In a major national security speech delivered last week, John McCain invoked his experience in Vietnam to explain his support for a significant U.S. troop presence in Iraq for as long as it takes to prevent a wider catastrophe in the region. "I hold my position because I hate war, and I know very well and very personally how grievous its wages are," the former POW said in an address to the Los Angeles World Affairs Council. "But I know, too, that we must pay those wages to avoid paying even higher ones later."

But the truth is that it's always about Vietnam for John McCain. He has invoked avoiding the mistakes of Vietnam with a sort of religious fervor in every important debate about dispatching U.S. troops since he first entered Congress in 1983. As he put it in an Aug. 18, 1999, speech to the Veterans of Foreign Wars, he studies "every prospective conflict for the shadow of Vietnam." In fact, a look at his record shows that he subjects every major foreign-policy decision to a Vietnam-derived test similar to the famed Powell doctrine, a test summed up by the McCain quote, "We're in it, now we must win it."

So entrenched are those lessons that McCain sounds, at times, like he wishes they could be applied retroactively. "We lost in Vietnam because we lost the will to fight, because we did not understand the nature of the war we were fighting, and because we limited the tools at our disposal," McCain said at a speech on Iraq at the Council on Foreign Relations on Nov. 5, 2003. And for that reason, it might be advisable to take him at his word when he says he'll stay in Iraq for 100 years. Whether Vietnam is the prism through which he judges national security decisions, or the rationale he uses to explain whatever position he decides to take -- and even if the lessons he says he's learned from Vietnam often seem contradictory -- he has applied his Vietnam test to Iraq and come up with the decision to stay.

Former Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger was one of the first to get widespread credit for boiling down Vietnam-like lessons into a short, never-again recipe. But most often cited is Weinberger's former senior military assistant, Colin Powell, who in 1991 as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff articulated what has become known as the Powell Doctrine. Powell, who served in Vietnam, created a series of questions that need to be answered in the affirmative before the commitment of U.S. ground forces. Though Powell himself never codified the questions on any single written document, they are generally agreed to consist of the following:

- Is there a vital national security interest at stake?

- Is there a clear and attainable goal?

- Have nonviolent efforts been exhausted?

- Is there a viable exit strategy?

- Do the American people support action?

- Is there broad international support?

Once the decision has been made to take action, the Powell Doctrine says that the application of force should be overwhelming.

As a member of the House and Senate over the past quarter-century, McCain has used his own version of the Powell Doctrine to analyze national security issues and explain his decisions. For McCain, the lessons from Southeast Asia are clear. Prior to committing U.S. troops, carefully define the objective of an engagement, determine if the goal is achievable and is a vital national interest and weigh the potential cost. Should military action begin, commitment must be total, force should be overwhelming, and action must be seen through to its conclusion.

But as horrifying as his POW imprisonment in Vietnam must have been, McCain's Powell Doctrine is not based on his own experience there. As an A-4E Skyhawk pilot, McCain was shot down over Hanoi in October 1967 during his 23rd combat mission and spent the next half-decade imprisoned until his release in March 1973. He set about learning the lessons of the conflict in Southeast Asia soon after he got back to the United States. McCain spent a year at the National War College at Fort McNair in southwest Washington pursuing a "personal tutorial" on Vietnam, according to Robert Timberg's "John McCain: An American Odyssey." He read everything from David Halberstam's "The Best and the Brightest" to the Pentagon Papers.

Ever since he got to Congress in 1983, McCain's mission has been avoiding or, if necessary, winning another Vietnam. His votes often show him trying to avoid another military quagmire. "John McCain voted the way Vietnam Syndrome would have dictated," explained Charles Stevenson, author of "Congress at War," who worked on national security issues for two decades as a Democratic Senate staffer.

And regardless of his hawkish reputation on Iraq, McCain's efforts to learn from history have resulted in him publicly questioning national security policy advocated by presidents of both parties. He has cast at least one unexpectedly dovish vote, and has voted against the majority of his own party more than once. He has also used Vietnam to support diametrically opposed positions. "You can look at it as he is independent and examines each decision on its merits or you can argue that he is inconsistent," said John Isaacs, who closely follows national security issues in Congress as executive director of Council for a Livable World. "I actually give him credit for not being knee-jerk."

Randy Scheunemann, the McCain campaign's director of foreign policy, says any apparent inconsistency is because the candidate does "not approach use of force issues with a cookie cutter and rigid list of criteria. He evaluates them on a case-by-case basis. And he also makes his judgments according to events on the ground, which can change over time."

Scheunemann did confirm, however, that the candidate applies a Vietnam-derived test very like the Powell Doctrine to military decisions. "The right way to think about Vietnam is, think very carefully about getting in before you get in, about the goals and how do you plan to achieve those goals. If you get involved, prosecute it to victory."

As one of his first high-profile acts as a freshman House member from Arizona in 1983, McCain shocked his colleagues by joining 26 other House Republicans in voting against President Ronald Reagan's effort to keep U.S. troops in Lebanon for an additional 18 months. During a debate long on references to Vietnam, McCain delivered a speech on the House floor on Sept. 28, 1983, that could have come right out of the Powell Doctrine playbook:

"The fundamental question is, What is the United States' interest in Lebanon? It is said we are there to keep the peace. I ask, What peace? It is said we are there to aid the government. I ask, What government? It is said we are there to stabilize the region. I ask, How can the U.S. presence stabilize the region? ... The longer we stay in Lebanon, the harder it will be for us to leave. We will be trapped by the case we make for having our troops there in the first place. I am not calling for an immediate withdrawal. What I desire is as rapid a withdrawal as possible."

Congress voted to keep troops in Lebanon anyway. Less than a month later, on Oct. 23, 241 service members were killed in the bombing of the Marine barracks in Beirut.

In the run-up the Gulf War eight years later, McCain, by then a senator, again used Vietnam to warn about the dangers of placing ground troops in harm's way. In the months leading up to the U.S. invasion of Kuwait, McCain repeatedly and publicly expressed serious concern about committing ground troops to the effort. "Listen, if there's one lesson of the Vietnam War, it is that you'd better have enough to do the job when you get there, so I don't know what the level of casualties are going to be," he said on Oct. 25, 1990, on CNN. "I believe that a scenario of 10,000 or so is not unreasonable or unbelievable, but I'll tell you this: We'd better not fight a tank-war battle on the ground. We'd better use what we've got the most of and the best of and that's our air power."

But on Jan. 11, 1991, McCain voted with his party and with the congressional majority in favor of using force. And again he invoked Vietnam. "During this debate," he said on the Senate floor, "we hear time and time again references to the Vietnam War and how we want no more Vietnams ... I think you could make an argument that if we drag out this crisis and we don't at some point in time bring it to a successful resolution, we face the prospect over time of another Vietnam War."

A year later, he used Vietnam to justify two contradictory decisions on the use of American military force. In a Dec. 3, 1992, interview, CNN's Frank Sesno noted that McCain had cited Vietnam as a reason for supporting the first President Bush's decision to send forces into Somalia. He asked McCain why Somalia did not carry the same risks as Lebanon, given that McCain had invoked Vietnam to explain his opposition to committing troops there.

"I see significant differences," answered McCain. "I do see a way in, a way to affect the situation, and a way out. I did not see that in Lebanon, when I opposed our deployment of Marines in Lebanon. I do not see that in Yugoslavia, as tragedy -- as tragic as that situation is." He also conceded that Somalia did not meet one of his Vietnam-derived tests of U.S. military involvement, but said he was setting that aside. "In this case, clearly United States national -- vital national security interests are not at stake, and that's usually a criteria [sic] that I always use. But the fact is that the magnitude of this suffering is so horrible and so inhumane that I think it compels us to act with other nations, but clearly with the United States in the lead, to try to alleviate this suffering."

On Oct. 10, 1993, McCain sponsored an unsuccessful amendment to cut off funds for the military operation in Somalia. Two things had changed since the previous December: A Republican president had been replaced by a Democrat, and on Oct. 3 and 4, 19 American soldiers had died in the debacle known as the Battle of Mogadishu and memorialized by the book and film "Black Hawk Down." On the Senate floor, McCain criticized the mission in Somalia as "some kind of warlord hunting, nation-building law and order endeavor, which has no beginning, no end, no clear-cut policy, no military objective ... Bring those young men and women home from Somalia and stop the killing."

Speaking about the resolution to Bob Schieffer on "Face the Nation," McCain used Vietnam to explain why he now wanted to leave. Oddly, he applied a Vietnam-derived lesson about "chaos" that was the precisely the opposite of the one he is now using to justify staying in Iraq:

"I would hope that chaos would not ensue if we left because I believe there's other United Nations forces which would take our place and, hopefully, carry out their responsibilities. But frankly, it's eerily reminiscent of the Vietnam rationale for remaining in there, and when we left Beirut after a disaster along the lines which we have now, we did not suffer from some kind of a serious loss of our prestige. There's so many holes in this argument for remaining there it's difficult in a short period of time to identify them all, but I can tell you right now, Bob, the American people are not c -- are not deceived by this. They want our troops out. They think we've completed our mission and I agree with them."

In the summer of 1994, McCain applied the kind of Vietnam-derived lessons he'd used to explain his desire to leave Somalia to oppose an invasion of Haiti, which President Clinton was considering. "I am opposed to an invasion of Haiti," said McCain on the Senate floor on Aug. 5. "I do not think it is in our national interest. I do not think it is worth the risk of American lives.

"I believe once we are there, without the ability to disengage, the ability to form some international force -- which we are finding nearly impossible to get together -- the chances of their succeeding are about the same as those of the multinational force that tried and failed in Somalia."

The next year, McCain seriously questioned the introduction of U.S. troops into Bosnia to enforce the Dayton Peace Agreement. Once they were there, however, he fought to continue funding for those forces, putting him at odds with other GOP lawmakers who were trying to cut funding.

But after weighing the situation in Kosovo in 1999, McCain decided that vital American interests were at stake. McCain agreed that the United States had a moral duty to protect Albanians there, but he also argued that a successful effort by Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic to defy NATO would embolden America's enemies across the world. He was one of 16 Senate Republicans to vote for the bombing campaign in March; he was also a reluctant supporter of an abandoned Clinton proposal to send 4,000 ground troops.

Once military action commenced, McCain became more hawkish on Kosovo than Clinton. After NATO airstrikes began in March 1999, Clinton announced that the United States would not be sending ground troops. McCain responded by introducing a resolution allowing the president to use "all necessary force," including ground troops, to get the job done. "Many of my colleagues oppose this war and would prefer that the United States immediately withdraw from a Balkan conflict which they judge to be a quagmire so far removed from America's interests that the cost of victory cannot be justified," he said in an April 20, 1999, speech on the Senate floor. "I disagree." It was in response to Clinton's reluctance to commit ground troops that McCain said, "We are in it, now we must win it."

In each of these conflicts, says Randy Scheunemann, differing circumstances explains his candidate's varying responses. "Lebanon and Somalia were fundamentally different from Kosovo and Iraq. In Kosovo and Iraq it was essentially a war against a state that had undertaken an action that needed to be reversed, whether that is conquering the territory of Kuwait or aggression against the people of Kosovo. In Lebanon the mission was essentially an interpositional force to hopefully provide some stability between warring factions. In Somalia, it was initially the delivery of humanitarian supplies and then escalating into seeking out some of the tribal factions that were preventing the delivery of humanitarian supplies. These are very different in terms of the type of intervention you are talking about, in terms of who the enemy is and what the goal is and how you would achieve victory."

In 2003, McCain unreservedly supported the invasion of Iraq. He predicted on the Senate floor as the invasion began on March 19 that "when the people of Iraq are liberated, we will again have written another chapter in the glorious history of the United States of America."

And by late 2006, when McCain famously tied his political fortunes to the upcoming escalation of troops in Iraq, he issued several more aphorisms he said were based on Vietnam. More than once, when asked about the stress longer deployments would place on U.S. ground forces, he said, "There's only one thing worse than an overstressed Army and Marine Corps, and that's a defeated Army and Marine Corps."

Unlike all previous military engagements during McCain's tenure as a politician, the Iraq war resembles in length and expenditure the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, and thus would seem to provide the clearest parallel for applying the lessons of the earlier conflict.

In fact, McCain has applied some lessons to Iraq that seem to conflict with earlier statements about Vietnam. He had previously said, in connection with Somalia, that staying in a war because chaos would ensue on American departure was not a good reason to stay. Last Tuesday, he said the U.S. needed to stay in Iraq because chaos would ensue if we left, as we learned in Vietnam. (And despite having shared in GOP rhetoric during the 1990s disparaging President Clinton's foreign policy initiatives as "nation building," he now publicly embraces remaining in Iraq to build democracy.

The prime lesson McCain seems to be applying to Iraq is that we need to stay in it to win it. In fact, McCain has argued that the United States' failure to adhere to that last maxim after a decade of war in Vietnam provides a "cautionary lesson" for the war in Iraq.

Some foreign policy experts think that the commitment of a large, long-term troop presence in Iraq does little to spark action in a lethargic political reconciliation process in Iraq, the ultimate key to success there. They draw a very different parallel with Vietnam. "It does not provide an endgame, which puts us right back in the problem of Vietnam in trying to push an ally or a host nation to try and change," explained Bruce Hoffman, a terrorism expert at Georgetown University. "We are giving them the breathing space because of our large force numbers, but their belief is that because we have made such a large commitment, we are not going to leave, so they don't really have to change."

Hoffman said McCain is "right to invoke Vietnam, but he is drawing the wrong lesson ... People misapply history to fit their view of the world. This seems like another example."

Speaking on behalf of the McCain campaign, Scheunemann said the Arizona senator has a very clear exit strategy for Iraq: "victory with honor."

"The reality is that we are starting to see some important signs of political reconciliation," explained Scheunemann. "Senator McCain believes that we would not have these positive developments had we not provided the increased security that has come with the change in strategy and the increased forces."

McCain said as much in his Los Angeles speech last Tuesday. It was odd timing, as fresh clashes erupted that day between Iraqi security forces and Shiite militias in the southern city of Basra and rockets rained down on Baghdad's Green Zone in yet another spasm of violence that threatens to spin out of control.

Shares